“It’s the heart of my studio”: The story of the Akai MPC, from the MPC60 to the MPC Live III

Few pieces of production gear are as influential as Akai’s MPC series. We trace the MPC's journey through its phoenix-like birth from the ashes of the LinnDrum 9000 to the latest apex-hitting incarnation

By the late 1980s, music production gear was reaching previously unseen levels of sophistication and accessibility.

Affordable sampling gear meant that workaday musicians could get their hands on technology that was hitherto only accessible to top-tier artists. MIDI was also making strides, allowing anyone with a few keyboards and a drum machine to craft fully-fledged, release-worthy songs in their home studio.

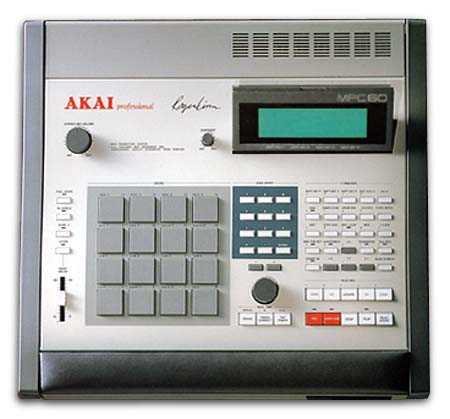

But what had yet to arrive was a compelling instrument that united all of this functionality – sampling, sequencing, and rhythm creation – under one hood. That is, until the release of the Akai Professional MPC60 in 1988.

Standing for MIDI Production Center, the MPC was like a bolt from the blue. It was the right instrument at the right time, bringing together the triple threat of drums, samples and sequencing into an innovative instrument that became an immediate hit.

Its sampling capabilities, its unique workflow and famous swing timing, and a revolutionary 4x4 grid of pads for banging in notes, the sampling capabilities – all of this came together to create a machine that changed music production forever. And continues to change it, as the MPC series has steadily evolved over the years, keeping up with the technological advancements and inspiring new generations of beatmakers along the way.

This is the story of the MPC, from its exciting beginnings as a new concept for music production to its recent reinvention as the MPC Live III, a modern take on the instrument that many are calling the best MPC yet.

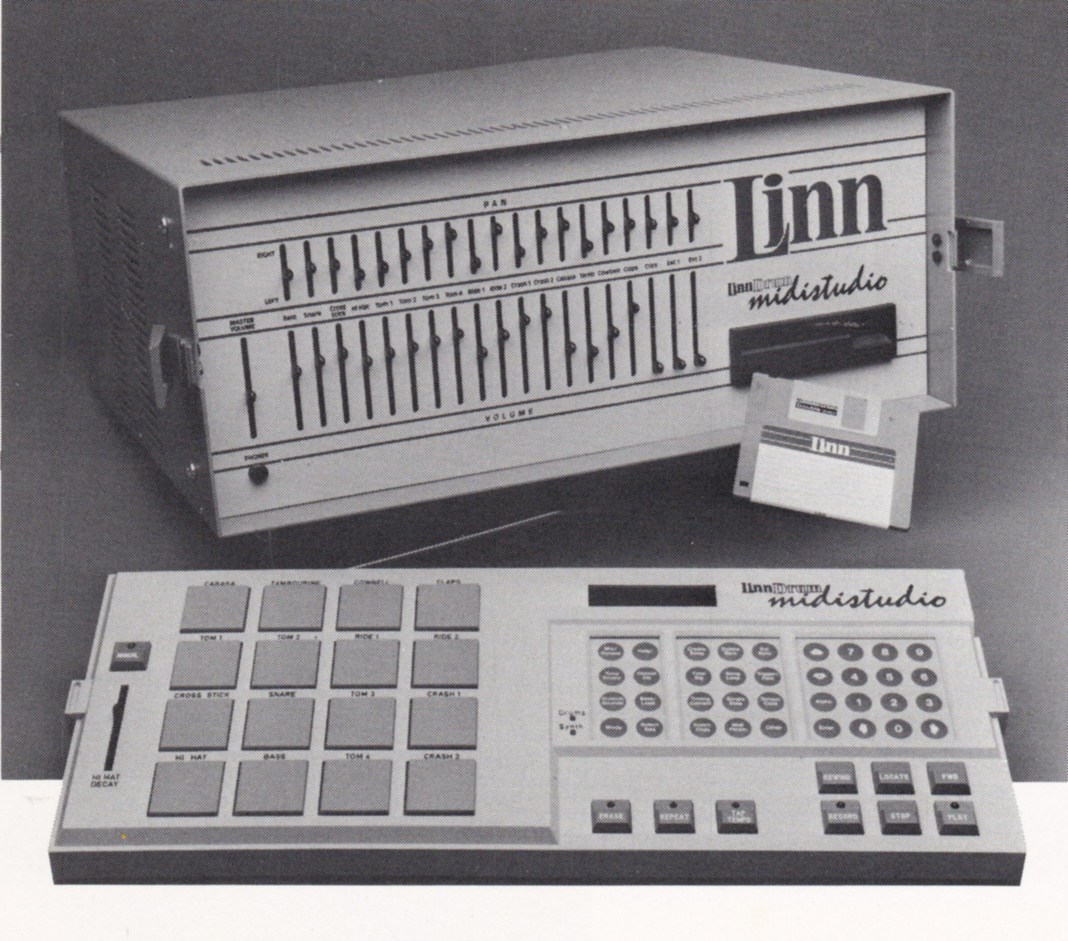

The epic tale that is the MPC starts not with Akai Professional, but with Linn Electronics and one Roger Linn, the father of the modern drum machine. Using sampled acoustic drum sounds, rather than the often-chintzy analogue approximations, and pioneering sequencing techniques such as swing, which slightly offset every other beat to mimic the feel of a human drummer, Linn redefined what a rhythm machine could be with the LM-1 and LinnDrum.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

While all signs pointed to the LinnDrum follow-up, the Linn 9000, becoming a hit, it was ultimately hobbled by buggy software and a price tag that was a little too aspirational. Linn also made the unfortunate decision to discontinue his previous models, assuming that customers would want the new one instead. They didn’t, and Linn was forced to close up shop.

This sad ending was, paradoxically, the happy beginning of the MPC. As Roger explains: “After my first company Linn Electronics went out of business, the newly-formed Akai Professional company contacted me about collaborating on a high-end drum machine.” Spun out of the Japanese electronics brand Akai in 1984, the new branch was to focus on music production equipment, such as synthesizers and—crucially—samplers, with the S series launching with the S612 in 1985, and the more famous S900 following in 1986.

After an introduction from mutual acquaintance Stephen Paine, the head of London-based music retailer Syco Systems, Roger was brought on board for a new project. “Akai was… strong in production, marketing and sales, but not so much in design and ideas,” he explains. “After some initial general discussions about their desire for a drum machine similar to my Linn 9000, I presented some engineering documents of what I thought we should make.”

Akai Professional had originally wanted to remake the LinnDrum MidiStudio, Roger’s intended successor to the 9000, as it featured all of the key elements that Akai wanted in its new product: a drum machine with sampling and sequencing. Roger wanted to shoot higher. “I suggested that it was better to use parts of it while upgrading other parts to better technology,” he says, “for example, using a new sound chip based on the chip they used in their S900 sampler.”

A truly international endeavour, the MPC came together with input from designers and engineers in the United States, England, and Japan. Says Roger: “[Akai] agreed and we began development, with me creating the functional design and UI, my team in California writing the software, Akai in Tokyo creating the circuitry and mechanical design, and UK engineer David Cockerell designing the sound chip.”

That David Cockerell being the same David Cockerell of EMS and Electro-Harmonix fame, who also worked with Akai on its sampling technology in the ‘80s. “I had close communication with David in London and Akai in Tokyo, and occasionally we’d all meet in Tokyo,” Roger explains.

When you think of an MPC, probably the first thing that comes to mind is the iconic (and now commonplace) 4x4 array of pads used for triggering samples. This was actually a holdover from the LinnDrum MidiStudio. “I had used a 4x4 pad matrix in the LinnDrum MidiStudio, which fit well on the left side of a large remote panel that could be removed from the front of the rackmount product,” explains Roger. “We used the same 4x4 pad matrix and sensing technology in the MPC.”

The sound, based around David Cockerell’s S900 chip, hit the sweet spot, with a punchy and crispy 12-bit, 40kHz sampling rate that turned drums into aural magic. It worked a treat with instrumental loops too, a use case probably not intended by Roger and team but something that producers cottoned onto almost immediately.

It also had that swing, the inimitable groove that dedicated MPC user and hip-hop producer The Alchemist calls “the neck snap.” Almost as famous as its pads, the swing on the early models is the stuff of legend. “The swing on the MPC goes from 50 to 75,” he said in an Aulart Masterclass. “There are some numbers I lean towards, and everybody finds their own. 62 or 63 is my comfort zone.”

With all of the pieces in place - sampling, drums, sequencer and pads - Akai Professional released the MPC60 to market with a price tag of $5000, coincidentally the same as the Linn 9000. Unlike that ill-fated machine, though, the MPC60 was a hit, thanks in no small part to its adoption by a rising subset of producers: hip-hop beatmakers.

The MPC wasn’t the first sampling drum machine to be embraced by hip-hop producers. That would be 1985’s SP-12 from E-mu, and its follow-up, the SP-1200 in 1987. But the MPC60 was a decidedly more sophisticated instrument, particularly with the inclusion of MIDI sequencing.

This drew in beatmakers like moths to a flame. When asked if they specifically targeted hip-hop producers when designing the MPC, Roger responded: “Hip-hop was still evolving at the time, so we didn’t consider hip-hop producers specifically, but rather any genre of beat-oriented music.”

The list of beatmakers working in hip-hop who used (and still use!) the MPC is long, including Dr Dre, Lord Finesse, Kanye West, Pete Rock, and of course J Dilla, who famously switched off the MPC’s quantization to create a loose and wonky rhythmic language now known as ‘Dilla time’.

One artist particularly famous for his love of the MPC is DJ Premier, who first used the MPC60 on his records with Guru as Gang Starr. Premier had been working with an Alesis HR-16 drum machine on the Daily Operation sessions. After getting turned on to the MPC60 by engineer Eddie Sancho, he realized, “This is what I need,” as he recalled in a video with Akai about discovering the instrument. Interestingly, his methods evolved to incorporate the S950, with the MPC60 acting as sequencer to trigger drums from the rackmount sampler.

"The MPC is a really raw machine. To make a beat with a lot of layers sound like a finished product is tough to do with the MPC"

The Alchemist, who favours later entries in the series, used the MPC 2500 and MPC Renaissance with artists like Mobb Deep, Eminem and Earl Sweatshirt, layering elements to create fleshed out loops. “Layering is how you create the magic,” he says in his Masterclass. “The MPC is a really raw machine. To make a beat with a lot of layers sound like a finished product is tough to do with the MPC. It’s not blended well enough sometimes, just coming out of this machine. So for me the trick is to add as many layers as you can.”

The limitations set by the MPC ended up becoming a major contributor to the vibe of 1990s hip-hop, what is often called its golden age. Firstly, there was the lack of effects on the earlier models, resulting in a bare-bones, upfront sound that prioritized the rawness of the original loops.

Along with the sonic fingerprint of the sampling algorithm itself, there was also the 13-second limit on sample time in the original MPC60. (Though this was upgradeable to 26 seconds, it’s still a shockingly small number compared to modern samplers like the Roland SP-404MKII and its 16 minutes per sample.) This forced producers to trim the fat and concentrate on what was most important in their beats, imparting an immediacy to the records that still stands today.

One producer that flourished within the MPC’s limitations is DJ Shadow. He famously employed just a single MPC60 to create Endtroducing, the landmark 1996 album that is more than just a collection of beats and loops, but a deftly woven tapestry of samples. For his collaboration with James Lavelle as UNKLE, he added an MPC3000 to his workflow, reaching an apex with his second album, the Private Press.

“The last project I did that was very MPC-intensive was my second album,” DJ Shadow said in 2023. “I had two or three MIDI’d together, and it was very much like, ‘on this record, I'm going to do everything that can possibly be done on the MPC’.” Since then, however, he’s abandoned the machine in favour of computer-focused production via Ableton Live. “Around 2008, I said alright, I've had it, I'm gonna go and get the newest MPC and go back to doing it that way. I lasted about a day and a half. When you know what the possibilities are, and then you try to go back in time to something that's constrictive, it just doesn't work.”

"I love the MPC3000. It’s the best machine to work with without a DAW"

Hip-hop is not the only genre that gets made on the MPC. As Roger Linn intended, it does indeed crop up on “any genre of beat-oriented music.” It’s featured in the kit lists of indie bands like the Cocteau Twins and LCD Soundsystem, appeared on records by John Mayer and Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, and had its pads bashed by AraabMuzik, who uses two of them side-by-side to create his genre-bending modern bass music live.

It’s also popular with house producers like Ian Pooley, whose MPC3000 remains the centerpiece of his workflow. “I love the MPC3000,” he says. “It’s the best machine to work with without a DAW.” Although he started off with an MPC60II in 1994, Ian finds the 3000 to be the perfect machine for him. “Over the years I’ve tried a few later models like the MPC4000 or the Renaissance,” he explains, “but I was never satisfied with the build quality and the workflow. The MPC3000 is the one for me. It’s the heart of my studio.”

When asked how he uses it, he replies, “It’s perfect for house music, not only for beats and samples. It’s great for programming basslines, stabs or pads.”

Roger Linn worked with Akai on two more MPC models, the MPC60II in 1991 and 1994’s MPC3000, the latter of which remains a high-water mark for many. With its 32-voice polyphony, onboard effects, and resonant lowpass filter, it helped to elevate the line, of which there have been 20 distinct models.

The evolution of the MPC continued with the 2000 arriving in 1997 with 16-bit sampling and a looper; the 2000XL in 1999 with its now-iconic tilt screen; and the 4000 in 2002 with 24-bit sampling and dual LFOs. Branching out into different form factors, the smaller and more portable MPC1000 arrived in 2003, while 2012’s Renaissance and Studio models pioneered the idea of the MPC as a controller that paired with your computer running Akai’s MPC software.

This was the genesis of the MPC-as-DAW idea, one that would have a profound effect on the future of the series. Akai took a massive leap forward in 2017 with the MPC Live, which saw the MPC Software make the leap from computer to device for the first time.

This year, Akai Professional released the latest incarnation in the series, the MPC Live III. Combining elements of both the MPC and Force devices with new features that advance what an MPC is ‘supposed’ to do, it feels exciting and fresh, and is being hailed by some as the best MPC yet.

“The goal with the MPC Live III was to push the limits of the standalone MPC experience while staying true to its heritage and legacy,” Akai Pro’s Andy Mac tells us. “We wanted to design a device that feels instantly familiar to longtime MPC users, but powerful enough to meet the needs of modern production, and incorporate new technology and features people haven’t seen before on an MPC.”

Those new features include things like stem separation, an improved processor that can run up to 32 plugin instruments, and a step sequencer running across the top of the interface. “We worked hard to deliver a new MPC that pushed the boundaries of what could be achieved standalone,” he says. “For example, individuals in the younger generation use step-based programming, as do electronic musicians, which is something the MPC never had before.”

Also new is an upgrade of those famous Akai pads. With 3D sensing, MPCe pads offer X/Y control of one-shot layers, sample blending, and note repeats. “Our goal was to introduce a new technology that pushed the boundaries of a conventional 16-pad configuration while honouring the classic MPC pad feel,” explains Andy.

Force-style clip-launching is another brand-new element that expands the MPC experience. Says Andy: “Clip launching felt like a natural evolution, and it was also a large request from the MPC community. It opens up new creative workflows without changing what makes the MPC unique; it's still tactile, musical, and deeply rhythmic, but now even more flexible.”

In the early 2000s, Akai quietly altered the branding of its MPC devices. What started as the MIDI Production Center in 1988 became the Music Production Center, a moniker that has come to encompass everything that MPC devices can do. Much more than just samplers with built-in sequencers, MPCs have become complete composition tools: a computer alternative that’s essentially as powerful as a PC, with a built-in DAW complete with plugin instruments and effects.

So where to next? It seems that there may be room in the market for a back-to-basics approach, a simpler model that harkens back to the heyday of the original units. “I wish they would release an MPC 3000 2.0, with all the essential modern-day features (storage, portability, etc.) but with the excellent build quality of the MPC 3000, and the unique swing that in my opinion none of the later MPCs could recreate,” dreams Ian Pooley.

Roger Linn, the creator of the series, would also like to see something on the simpler side. “I think the new MPCs offer a very good value for the price,” says Roger. “I also like how they use high-end ARM processors, Linux and big touchscreens, offering a viable alternative to computer DAWs. The only thing I’d prefer is if they would be easier to learn and use, but I’ve given Akai some suggestions for improving this.”

Wherever Akai chooses to go next next with the MPC, one thing is for sure: music-makers will surely follow.

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.