The ultimate guide to the circle of fifths and how it can help you make better music

Frequently seen but often misunderstood, this essential music theory learning tool can help you come up with creative gold

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Don't be afraid. The circle of fifths looks confusing but it's only ever here to help. And a basic understanding of what it's trying to tell you could lead you down a whole new creative superhighway.

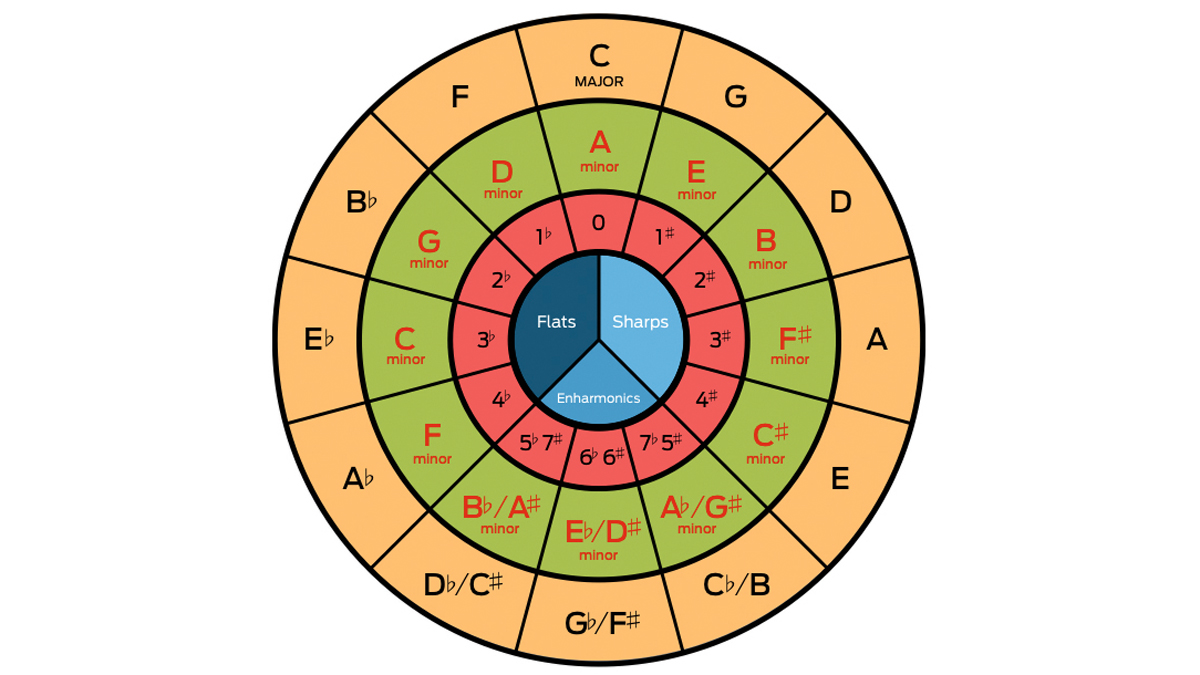

Simply put, it's a diagram that lays out the relationship between every musical note, key, three-note chord and scale and thereby suggests where your melody or chord sequence might 'go next'.

You're basically getting a suggestion for what 'goes with what' and what 'sounds right' for every next step on your musical journey.

Article continues belowBut what does the circle of fifths actually do for us? Let’s find out...

So what is the circle of fifths?

It's a scheme used by guitarists and keyboard players to suggest what chord might sound good next. It’s a chain of options that always works, always sounds logical and is the underpinning influence in songs as diverse as Frank Sinatra's Fly Me To The Moon and Gloria Gaynor’s I Will Survive to modern hits like Love You Like A Love Song by Selena Gomez & The Scene.

If you’re jamming with your band and can’t come up with an idea, knock-em-dead by strumming the circle of fifths.

Similar keys

At its simplest level, the circle tells us which keys are the most similar (and therefore sound musical and less of a 'leap' to move between).

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Similar keys are keys whose parent scales differ only by one note - eg, C major (C D E F G A B) and G major (G A B C D E F ) contain almost all the same notes except for the F, which is F# in G major and F natural in C major.

That's why they're next to each other on the outer ring of the circle.

Pick a key on this outer ring, and either adjacent key will only be one note different. Because of this similarity, a lot of music tends to change key by moving between adjacent keys on the circle.

Dissimilar keys

The circle also tells us the least similar keys. Spaced 180 degrees across from each other, you’ll find the keys with the fewest notes in common - that is, just two notes. So, the key of C major (C D E F G A B) and its opposite number F# major (F# G# A# B C# D# F) share only the notes F and B.

The interval between two directly opposite notes on the circle is always a tritone (six semitones) - handy when figuring out tritone substitutions.

Relative keys

The circle also groups together all 12 major keys with their relative minors. The 12 major keys are around the outermost ring (in orange) with their relative minors in the next ring (in green).

A relative minor is simply the minor key that uses the same notes as a particular major key, and vice versa.

So, looking at the circle we can see (at the top) that the relative minor to C major is A minor.

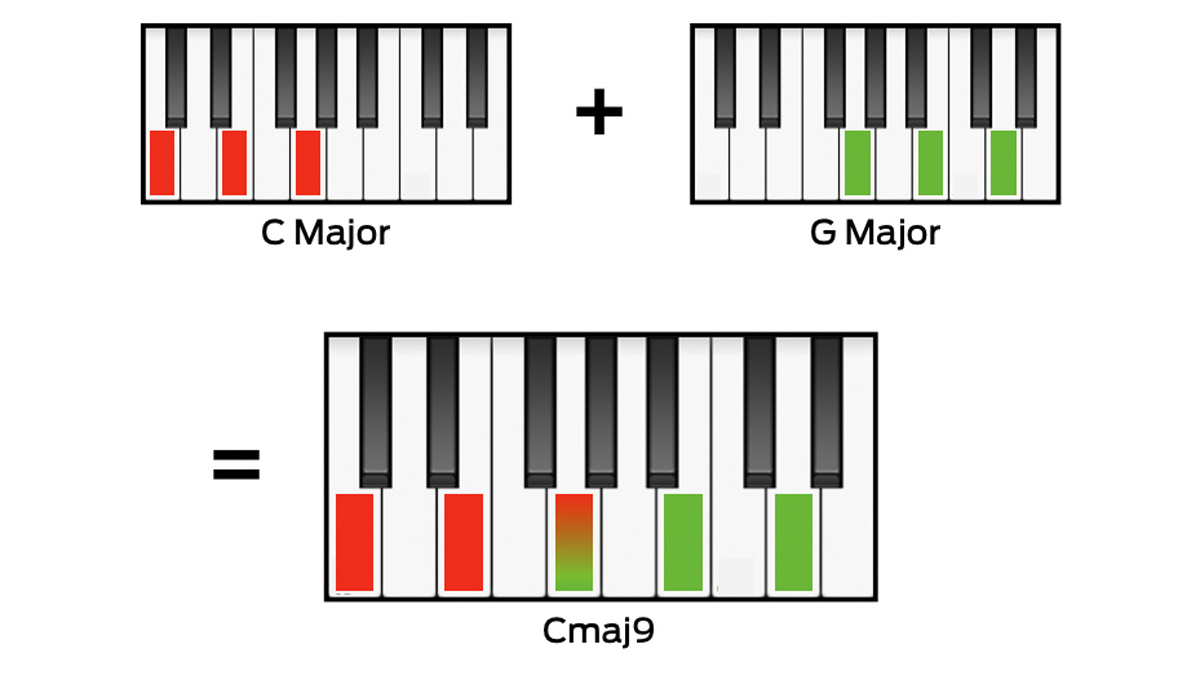

A C major triad chord (i.e. three notes at once) is formed by playing C (the root), E (the major third), and G (the perfect fifth) together at once.

Meanwhile the A minor triad is formed by the notes A (the root), C (a minor third) and E (a perfect fifth).

i.e. The two chords are very similar – with just one note difference.

Therefore it follows that the transition from C major to A minor will sound natural and not be too much of a jarring jump. i.e. Moving from C major to A minor (or vice versa) will simply 'sound good'.

10 things that every music producer needs to know about chords

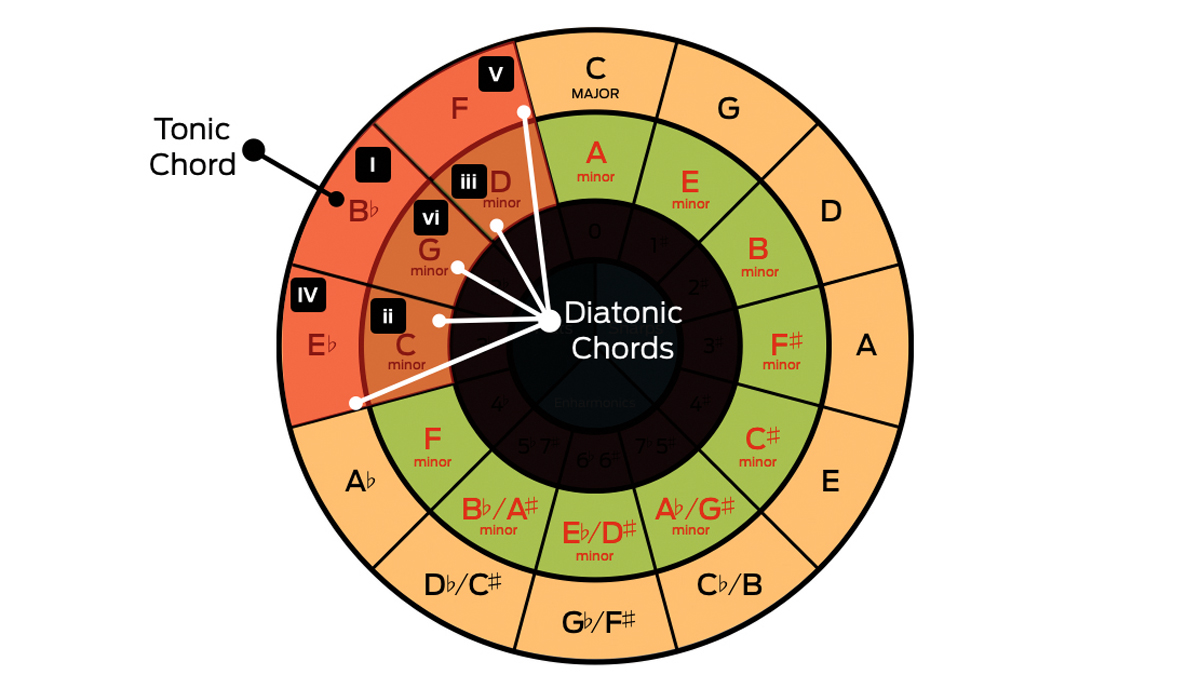

Diatonic chords

Diatonic chords are chords built entirely from the notes of a specific scale, whether major or minor. They form the foundation of harmony and chord progressions within a given key. Each note of a scale can be the root of a diatonic chord, creating a unique set of chords related to that scale.

The next ring in (the red ring) tells us how many sharps or flats are in each key. As you go clockwise from the top, each key adds one more sharp until you get to seven sharps (C# major).

Conversely going anti-clockwise from the top tells us the number of flats, adding a flat each time until you end up at seven flats (Cb major).

Borrowed chords

Borrowed chords are chords that are not part of the current key but are borrowed from a parallel key. Shifting from one chord to a 'borrowed chord' can sound unexpected and interesting.

The circle can show you the diatonic chords for the parallel key to the one you’re currently in. Choose your tonic note, then locate its parallel key by finding the same note on the other ring. Now just select a chord to borrow from the palette of five chords that immediately surround it on the circle.

Finding 3rds

For a quick way to determine major and minor 3rd intervals (without a keyboard), simply count four steps clockwise from the tonic to find the major 3rd, or three anti-clockwise from the tonic to reach the minor 3rd.

Order of events

There are several mnemonics (memory aids) you can use to help you remember the order of keys on the circle. For the sharp side (clockwise), there’s Charlie Gets Drunk And Eats Beetroot, while for the flat side (anti-clockwise), you could go for Charlie Forgets BEADs.

You can also use mnemonics to remember the order in which sharps and flats are added to a key signature to indicate each successive key. These include Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle for the sharps and Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father for the flats.

Enharmonic keys

When we get to the lower section of the circle, things get interesting key-wise. The keys with five, six and seven sharps (B, F#, C#) continue clockwise around the circle, overlapping with those that have five, six and seven flats (Db, Gb and B) as they continue from the anti-clockwise direction. So, for instance, F# major with its six sharps and Gb major with its six flats are the same key with two different names.

The same goes for their relative minor cousins, D# minor and Eb minor. Known as ‘enharmonic’ keys, these keys have dual identities according to whether you’re dealing with sharps or flats.

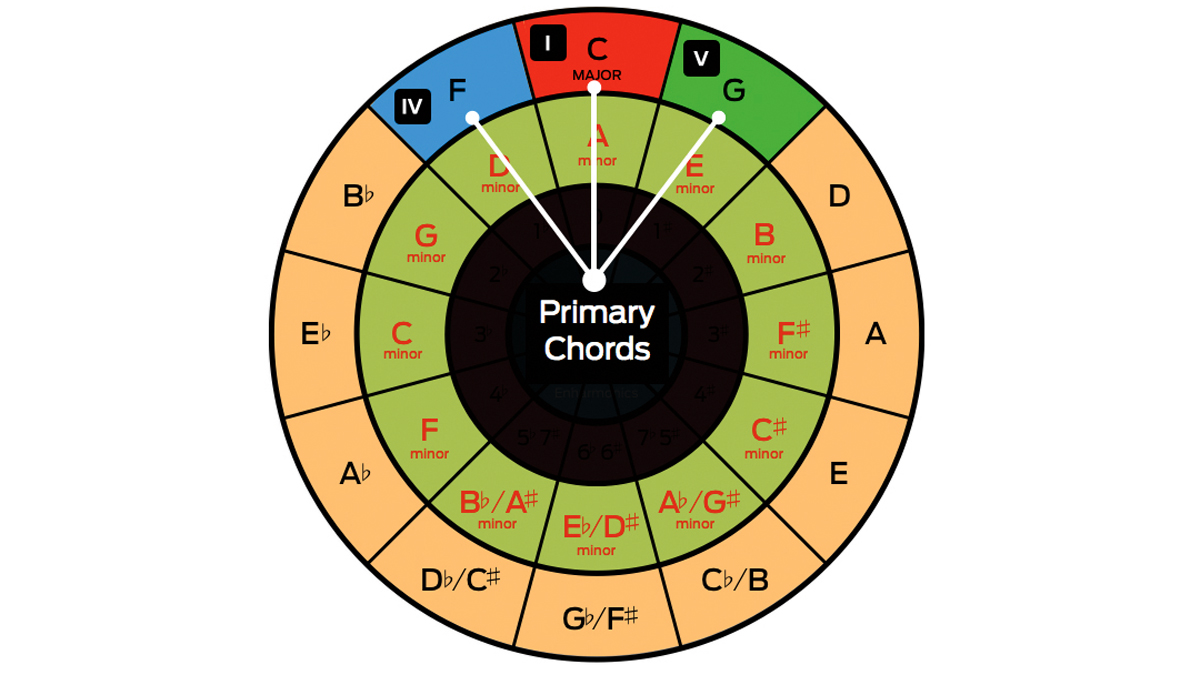

Primary chords

Pick any chord on the circle to be the I chord (or tonic), then the chord to the left will always be the IV chord, and the one to the right will always be the V chord. Known as primary chords, these are the basis for literally thousands of songs, particularly when used in what’s known as the I - IV - V progression.

Adding relative minor

Building on the above, you can expand the I - IV - V progression by squeezing in the relative minor to the tonic, which you’ll find on the inner ring of the circle in the same segment as the tonic. For example, I - vi - IV - V in the key of C major would give you C - Am - F - G, or, as another example, in the key of A major, A - F#m - D - E.

Minorising chords

The ii - V - I progression is one of the most widely-used musical phrases there is, especially popular as a jazz turnaround, used to return to the tonic.

To find the minor ii chord in any key, just count two notes over clockwise from the tonic and ‘minorise’ that chord. From there, step anti-clockwise back two steps to hit the V and I chords. For example, a ii - V - I in the key of D would be Em - A - D.

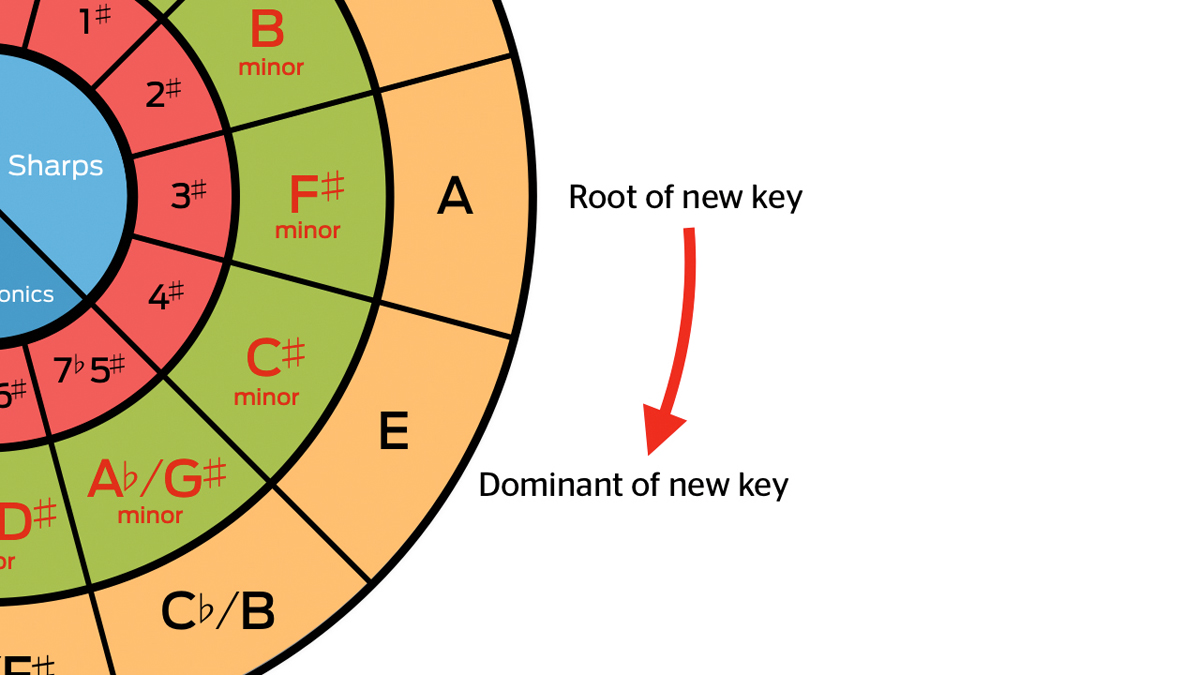

Easy key changes

The circle can even help with easy key changes that use the dominant 7th of the new key as a method of modulation, placing the dominant 7th before the change to the new tonic chord to prepare the listener.

For example, to change key from G major to A major, find the new key’s root (A) on the circle, and the next note over clockwise will be its dominant - E, in this case.

So the dominant chord you need for the key change is E7: G - E7 - A.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.