“Some of this stuff is harder to get hold of than rare analogue synths”: Why we’re in the midst of a vintage software revival

Meet the musicians that archive, compose and perform with obscure and abandoned music software

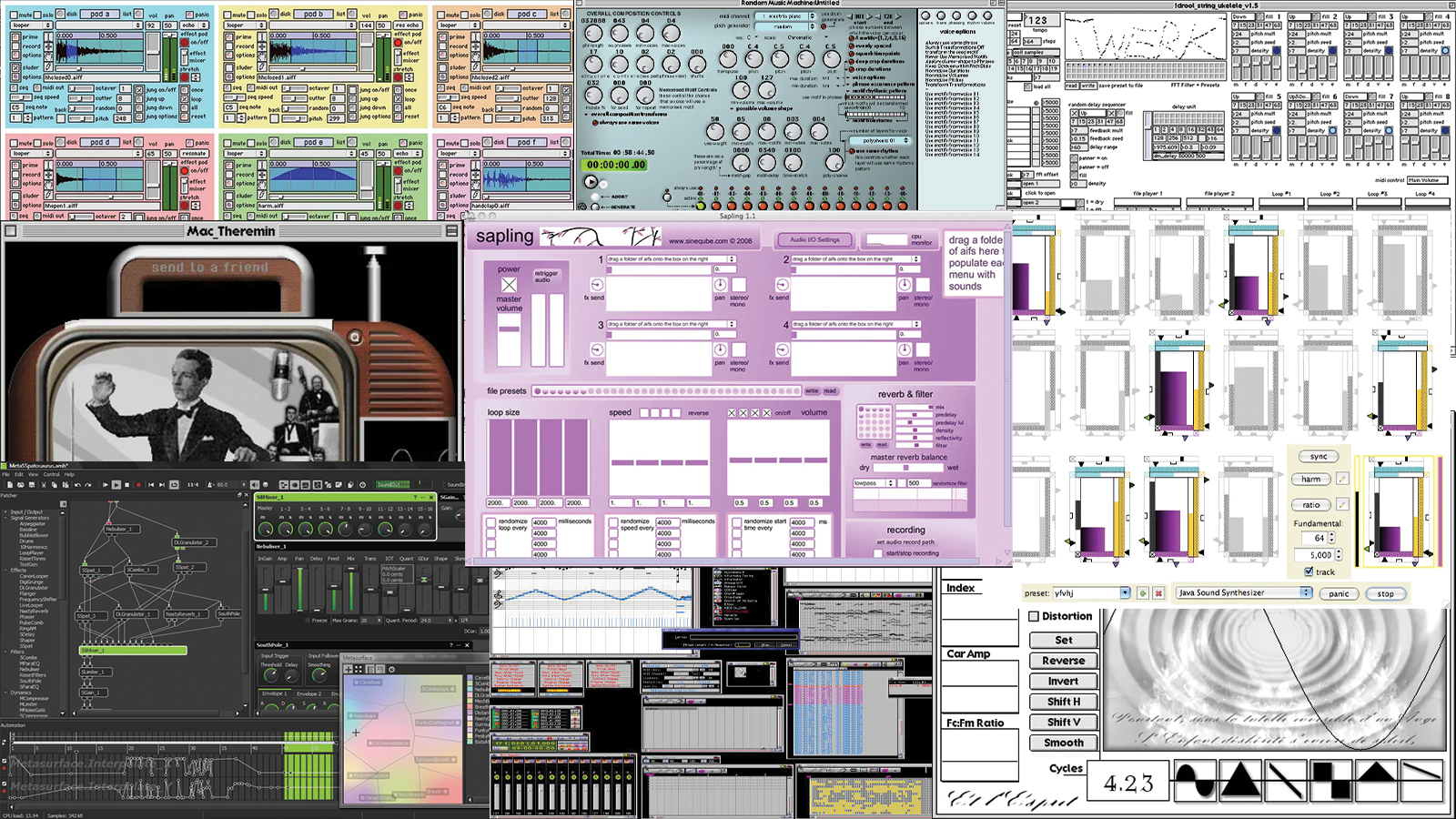

There was a time when music software felt joyfully chaotic. Each new plugin looked like a wholly distinct species, programs frequently crashed, applications often arrived with minimal documentation and required days of trial and error before you could coax them into spitting out sound, and some of the coolest stuff could be picked up for nothing on obscure personal websites or labyrinthine forum threads.

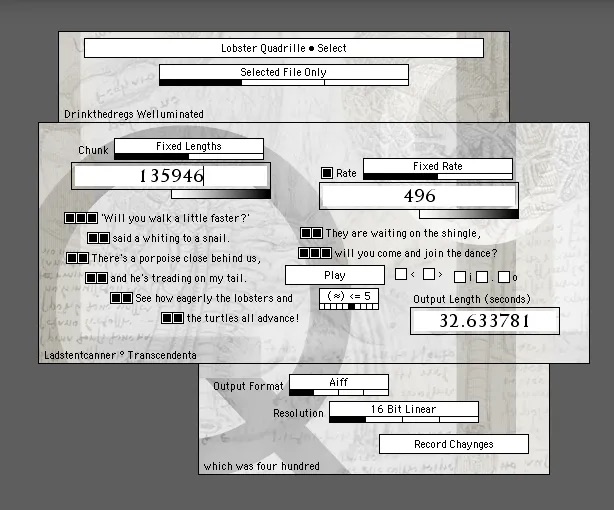

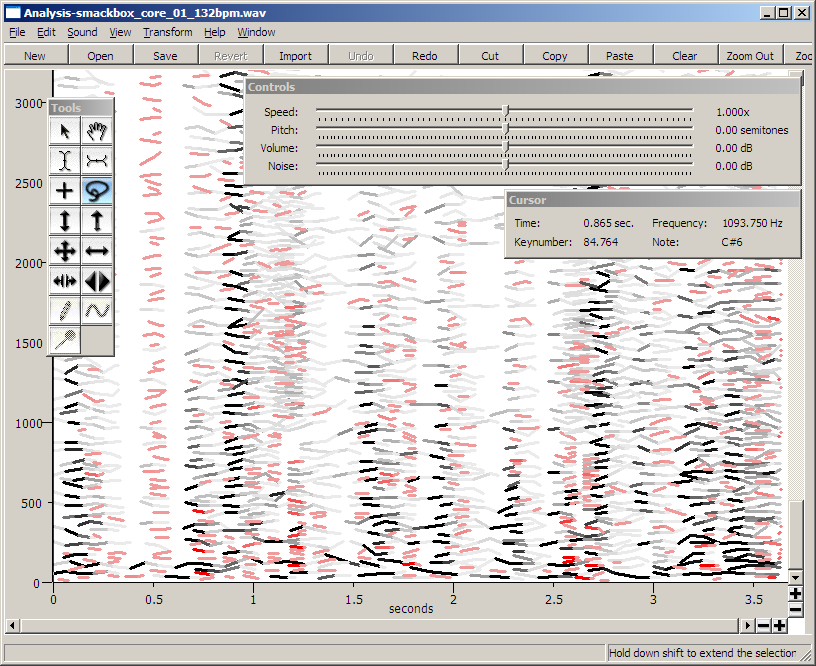

Those willing to search for it were rewarded with some of the most powerful, groundbreaking, weird and downright fun pieces of software ever created: tools like Spear, which broke sound down into its base elements and then resynthesized it into a ghostly doppelgänger, or MetaSynth, which allowed you to upload images and use their pixels to manipulate sound waves.

Over the years, one by one, many of those trailblazers winked out. The relentless pace of OS updates and the changing architecture inside our PCs and laptops left many unusable, abandoned or obsolete. Or, at least, they were.

Eschewing classic synths in favour of classic software, a growing number of musicians have begun to resurrect these once-forgotten tools and put them to back to work. They gather in places like the Obsolete Music Software Facebook group, which collects and chronicles rare and sought-after digital audio tools. Founded by Jeremy Williams in 2018, the group has become a space for VST veterans and novices alike: stories are swapped, technical tips are traded, and the original architects that wrote the code occasionally stop by to share some knowledge.

Initially, the group was “dead and small” by Williams’ own admission, but, starting around 2021, he and his fellow admins began to see an exponential increase in membership, growing from a “couple hundred” people into the 30k-strong community it is today.

Exactly what’s driven this renewed interest is hard to pin down – it might just be that enough time has passed for this kind of outmoded software to attain an alluringly ‘vintage’ vibe.

“You do need time for things to grow in their nostalgia,” Williams allows. “You can’t miss something that is always there, right?” While he recognises the role of nostalgia in the community, he’s also quick to point out that, in his opinion, there’s much more to it than that. “It goes way deeper than nostalgia – I’d list nostalgia towards the bottom, personally.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Rear-view mirrors have an undeniably rosy tint, but a strong argument can be made that the ‘90s and early ‘00s truly were a golden age for music software. The decade that closed out the 20th century saw massive advancements in the speed and power of computing, and a commensurate boom in consumer-ready DAWs.

By the time VSTs hit the market in 1996 plugins had become the new frontier of music production, and over the following years, large companies like Steinberg, small teams like Camel Audio, and independent solo developers all tried their best to outdo one another.

Moreover, the rules of digital music production were still being written: the ideal UI, the most efficient workflow, and the very fundamentals of digital signal processing were up for debate and experimentation. The diversity of that development environment in turn cultivated a genuinely eclectic spectrum of products.

“Our archive is an attempt to make these wares and related information a bit more accessible, so others don't have to trawl endless threads and 404 errors like we did”

“Anyone willing to learn SynthEdit or other such programs could create a VST,” Williams recalls of the time period. “As a result, some early VSTs may sound kinda wonky, sometimes the tuning was kinda weird or something was just off – and that’s what made it shine for anyone who dug deep. There were many unique and forgotten things made.”

For those hoping to actually find and use some of these antique algorithms, .DSP/archive is an indispensable resource. Founded by Elin and maintained by a small team of fellow enthusiasts, the endeavour is focused on the painstaking work of sourcing, validating, and hosting install files, along with resources to help people get started using them.

After writing a research paper on the archiving of digital audio at university, Elin became keenly aware of just how quickly software can vanish or become unusable. “That study opened my eyes to the volatile nature of digital media,” he says. “File formats and architectures frequently change, software is updated, licenses expire, hardware moves on.”

Putting together the archive involved an “incredible community effort”, one that often required digging through the internet archive and trawling forums on the off-chance that installation files were still gathering dust on someone’s hard drive. “Our archive is an attempt to make these wares and related information a bit more accessible,” says Elin. “So others don't have to trawl endless threads and 404 errors like we did.”

What’s striking about the community that surrounds this software is the sense that collecting and archiving is not an end in itself. A large number of the posts on the Obsolete Music Software group and related forum threads are concerned with making new music using these tools – not out of some purist principle, but because they still offer an inspiring and powerful way to create sound.

“I think users value alternatives to commercial DAW environments,” Elin says of people’s motivation. “Personally, composing on a timeline and grid is like ironing socks for me. It doesn't have to be like that – you can do almost anything you want!

“I’m fond of offline processing tools like SoundHack and Argeïphontes Lyre. In these non-realtime programs, you must decide how you want to affect a sound, and then wait for it to render. This way of working can yield unexpected results, but it takes a lot of patience.”

"Composing on a timeline and grid is like ironing socks for me. It doesn't have to be like that – you can do almost anything you want!"

Williams agrees that “different workflows create different results”, and also points to older software’s unique sound quality as a reason why he uses it to make his music. “I’ve always seen a trend of producers who obsess on the latest plugins,” he says. “But I like having these old tools around because it’s not going to sound like anyone else. I’d rather sound unique and be unknown than sound just like the latest trend and not be truly distinguishable.

“To this day I’m still obsessed with certain VSTs and standalone programs,” Williams continues. “There is this group of VSTs by MDA that do not have their own GUI, but some of them are super useful and to the point – like RePsycho! for some odd pitch adjusting and this decaying gate sequence sound, and there are super harsh buzzy grainy things like the ones by Insert Piz Here.

“In seven years, I don’t think we’ve gone more than two weeks without someone mentioning Delay Lama in the Facebook group. It’s always a good laugh but it shows that that VST was fun for so many. We joke that he is the group mascot.”

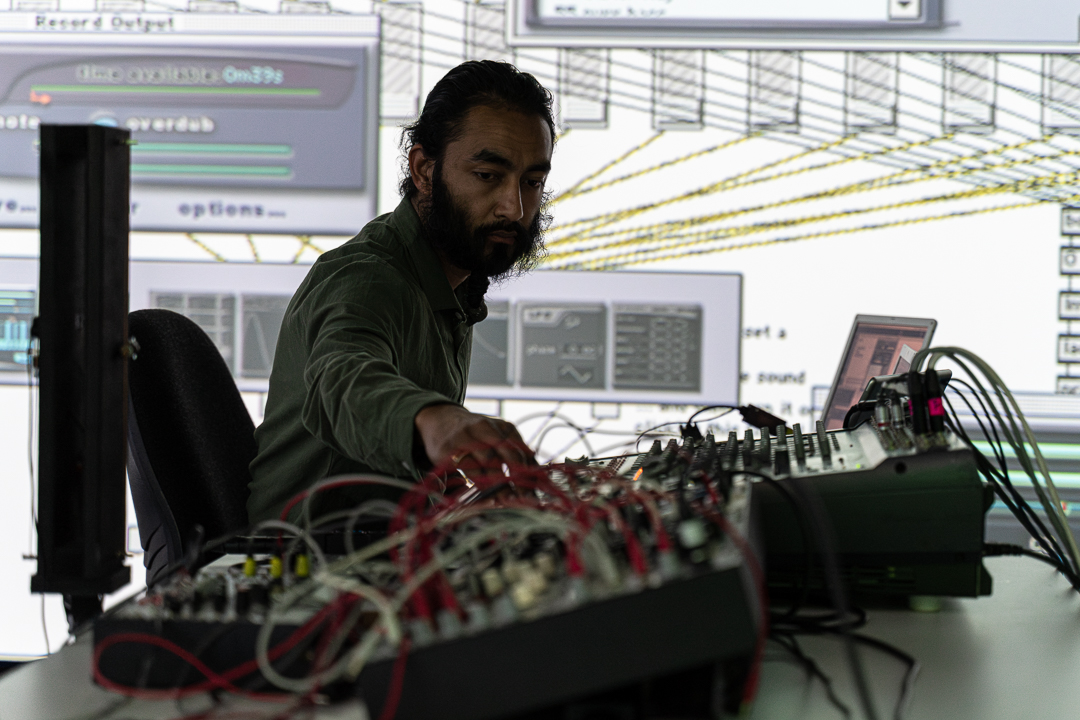

Suren Seneviratne, better known to the world as My Panda Shall Fly, not only uses classic software to write and record new music, but has taken to performing live with it as part of his Missing Music project. Having been raised on a diet of late '90s UK garage, Seneviratne says his early experiences teaching himself music production using a Windows PC and a selection of pirated audio tools instilled in him a love for the “golden era” of experimental music software.

"I felt like these things were so precious; these were important artifacts of electronic music"

In many regards, his current efforts are an attempt to fill in the gaps in his knowledge, and to get his hands on the software that he missed out on back then. “I'd always been a Windows user,” says Seneviratne. “There was just a whole bunch of stuff that I never had access to because it was only available on Mac. I was curious, and, because I’m an obsessive person, that curiosity just grew till I just had to play with this stuff firsthand. I bought a secondhand Apple iBook G4 laptop off eBay. That was the start of the rabbit hole.”

Seneviratne admits he wasn’t prepared for the sheer volume and variety of music software available on Apple hardware, nor was he prepared for how hard it would be to find rarer items. “Some of this stuff is harder to get hold of than rare analogue synths,” he emphasises. “I felt like these things were so precious; these were important artifacts of electronic music. As I was discovering and testing and playing with them, I just couldn't believe how incredibly powerful and fun they were.”

Initially, the Missing Music project served as a blog, cataloguing Seneviratne’s discoveries with screenshots and product details. Over time, as these tools began to play a more significant role in how he created music, as the potential to bring them into a live setting became clear. “I don't know why it took so long,” he reflects. “After a while it clicked that these are still living, usable tools. I just thought ‘I can take this blog onto the stage.’”

Performing live music in front of a crowd can be a nerve-wracking experience – doing so using authentic, two-decade-old hardware and software would be enough to make many musicians break out in a cold sweat.

Having now performed over 30 improvised live sets without any major disasters, Seneviratne trusts in the capabilities of these older operating systems: “In the forums that I loiter in, the Mac OS 9 architecture is still regarded as one of the best and fastest for making music. It’s obvious why that is – there's nothing eating up unnecessary resources on the computer, and that just means it's a very fast, stable kind of environment.”

A core element of how Seneviratne connects this project with an audience is by making each software’s UI visible. Using a pair of video projectors, he’s taken to beaming his desktop screen onto the performance space. “My criteria is that the plugins I use onstage have to sound good but also look interesting,” says Seneviratne. “The visual language of this stuff is something I love, so I project my screen because I want people to see and to know exactly what's going on.”

"As we see a rise in AI, there could be a rebellion of musicians who purposefully retreat to these old, off-grid software methods to make music"

While there is clearly growing interest in this subculture, the primary barrier for any would-be users has always been, and will likely remain, the issue of compatibility. Whether you’re purchasing secondhand computer equipment or undertaking a multi-step process to emulate these programs on modern machines, it’s a far cry from the streamlined, and arguably simplified, workflows that dominate today’s music production space.

However Williams believes that this creative friction could increasingly be seen as a virtue. “Personally, I’ve started to humour this idea that as we see a rise in AI, and other tools that skip a ton of steps to get to the end result with less and less effort, that there could be a rebellion of musicians who purposefully retreat to these old, off-grid software methods to make music. That sounds somewhat cyberpunk and fun.”

"It is important for the history of music for us to archive these things"

That future, or any other which involves classic software, depends entirely on efforts to seek out, preserve, and share this software – something that many in the community are keenly aware of. As Elin points out, digital preservation is in a state of crisis. With the Internet Archive under increasing legal threat, he believes it is important to “decentralise and form independent communities.”

Williams has a similar stance: “Despite what we've all been told, not everything stays on the internet forever. This is why it is important, for the history of music, for us to archive these things.”

Whether you term this software as historic, vintage, rare or classic, one thing it really can’t be called is obsolete. The programs that powered early digital music are clearly alive and well, supported by a vibrant and thriving culture of collecting, sharing, creating, and performing.

You might then think that ‘Obsolete Music Software’ is an odd moniker for the online group that has become a central meeting point for that community – and you’d be right. “The group name is a joke,” Williams confides. “We don’t believe any of this is obsolete.”

Clovis McEvoy is a freelance writer, composer, and sound artist. He’s fascinated by emerging technology and its impact on music, art, and society. Clovis’ sound installations and works for virtual reality have been shown in 15 countries around the world.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.