“All contemporary pop utilising computers and samplers owes something to the innovations of Trevor Horn”: How Trevor Horn’s anonymous electronic group - the Art of Noise - revolutionised sample culture

Discover how studio and music production was redefined by an unlikely group of Trevor Horn-led English synth geeks

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

RECORDING WEEK 2025:“All contemporary pop utilising computers and samplers owes something to the innovations of Trevor Horn in the early eighties,” said journalist and agent provocateur Paul Morley on the radical studio work of his Art of Noise comrade.

The group - featuring engineer/producer Gary Langan, programmer J. J. Jeczalik, and keyboardist/arranger Anne Dudley alongside producer Horn, and the music journalist Morley, was an unlikely ’80s success story.

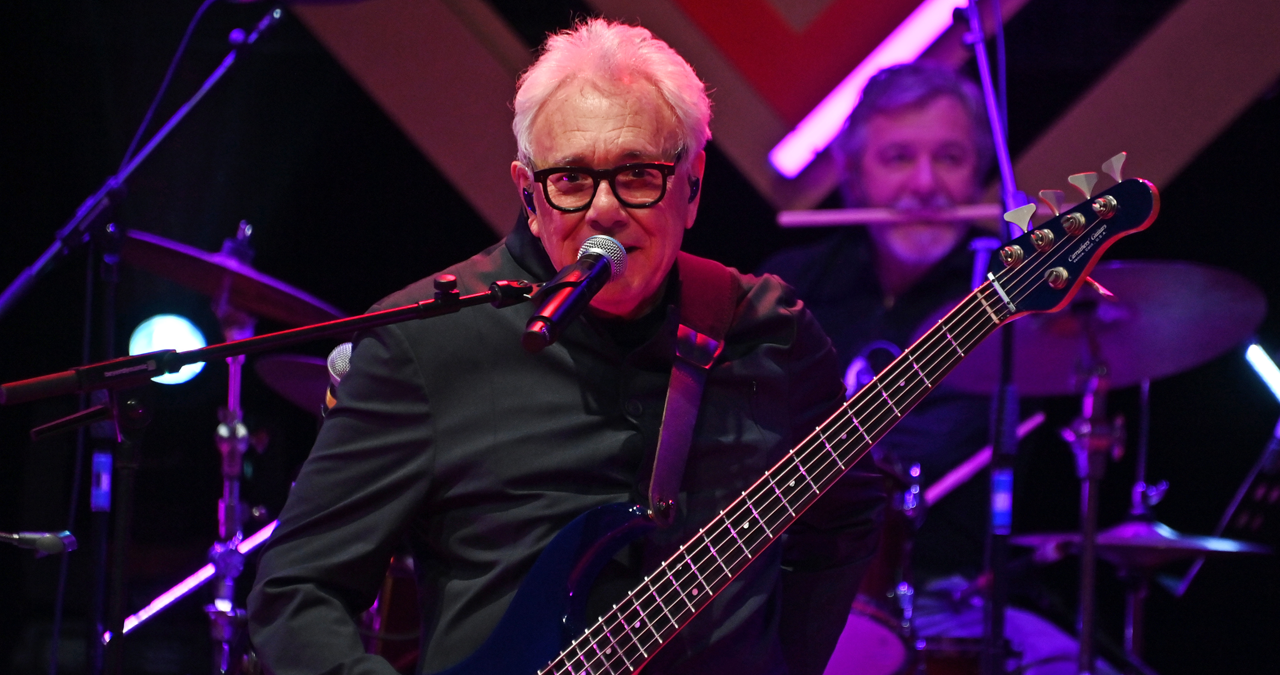

Previously working as a session musician, Horn had found acclaim as a bass player in the 1970s, then scored a hit as one half of Buggles with the iconic Video Killed the Radio Star (more on that here) and fronted the prog-rock-pop band Yes.

During the following decade, he pivoted to music production, forming an unlikely bond with an English studio team that empowered him to cement the foundations of electronic music, sample culture and even the early days of hip-hop and breakbeat.

The Art of Noise was an anomaly and everything that the decade’s reliance on guitars and rock posturing was not.

Instead of guitars, bass, drums and vocals, the Fairlight CMI sampler was at the core of their sound and, rather than traditional musicians as band members, these were studio engineers and programmers.

It was this team and Horn’s own ZTT records that led to the release of their classic debut album, Who’s Afraid of the Art of Noise? in 1984 - and their singles, Close (to the Edit) and double A-side, Moments in Love/Beat Box.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The group was not only known for their innovative use of the studio as an instrument but also their anonymous collective persona.

Paul Morley told the Guardian: “People didn’t know where we had come from. We were often labelled radical underground dance artists. We even got an award in the US for best black act of 1984. I think I made my excuses.”

Trevor Horn first cut his musical teeth as a bass guitarist, having picked up the double bass in his school orchestra. With the rare ability to sight read, his skills as a session musician for hire were much in demand, meaning when he moved to London during the 1970s, he found numerous opportunities.

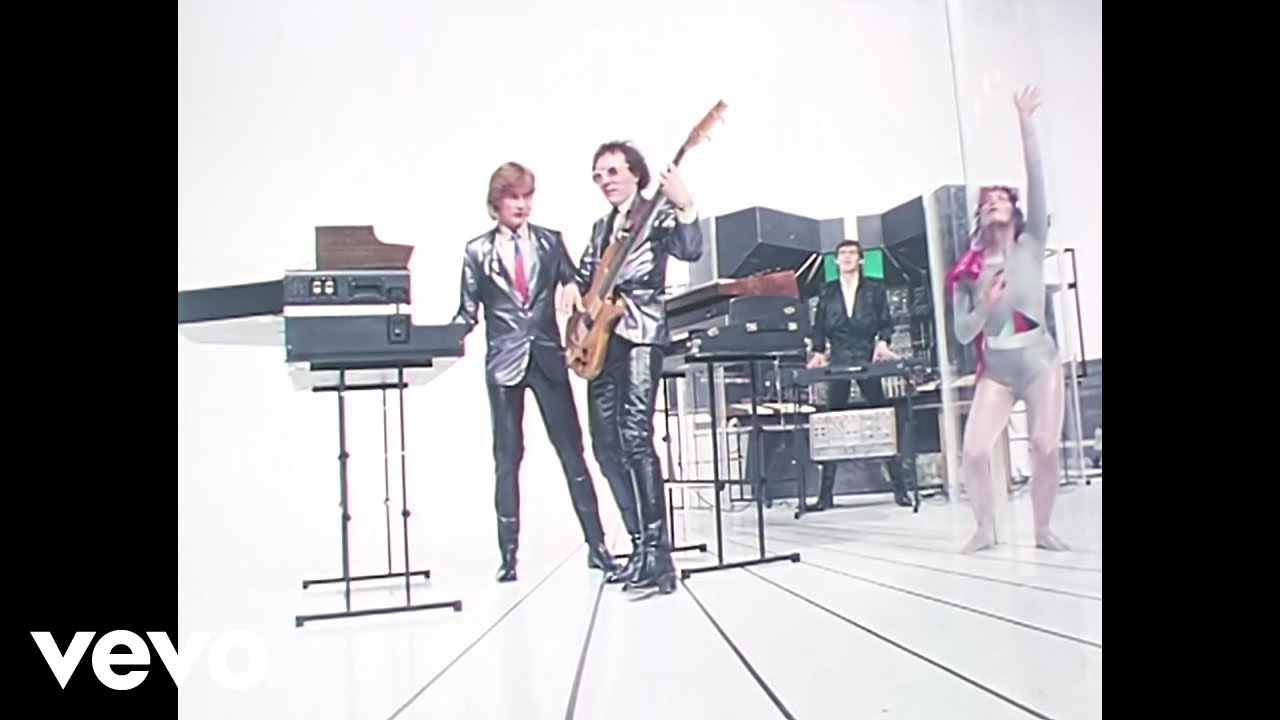

It was as one half of the Buggles and their electronic pop hit, Video Killed the Radio Star where Horn first embraced technology. Working with collaborator Geoff Downes, Horn drew on his love for the dystopian novels of JG Ballard and synthesised beats of Kraftwerk to come up with a pop classic that hit the top of the charts and became the first video played on MTV.

On release in 1979, the track was a global smash, showing Horn’s devotion to seek out the latest studio gear to realise his musical ambitions.

The duo utilised the Solina String Ensemble, Yamaha CP-80 electric grand, Moog Minimoog, Prophet 5 and Roland System-100 to create their futuristic pop sound.

Horn added to it with a TR-808 drum machine and a CSQ-600 sequencer before the royalties started to flood in from the success of Buggles.

Downes subsequently treated himself to the Fairlight CMI, a pioneering sampler and synth billed as a groundbreaking ‘Computer Musical Instrument’. After Buggles faltered with Downes leaving to play with rock band Asia, Horn realised that he would have to take the plunge and invest in his own. Despite a then-eye-watering price tag.

As dance music historian Matt Anniss writes, the Fairlight, “Introduced the world to the idea of sampling and sequencing …. what had started life as an attempt to make a killer digital synthesiser eventually turned into the world’s first fully-fledged computer music-making system”.

Kim Ryrie is an Australian synthesiser inventor who founded the audio technology company Fairlight with fellow tech enthusiast Peter Vogel. Little did the pair know that their creation would come to dominate the sound of the 1980s, utilised by the likes of Kate Bush, Herbie Hancock and of course Trevor Horn.

The Fairlight CMI’s appeal came via it being one of the first synths to come with its own workstation and, crucially, the very first commercially available sampler.

When it first launched, it was the toy of the wealthy - this was obviously a long-time before we could produce music on our phones or tablets - and cost as much as a home at the time.

However, when the first sequencer, the Page R, was featured on the second version of the CMI in 1982, its potential to change music production came to the fore.

Speaking in an interview from April 2025, Horn said: “The thing about the Fairlight was that it changed the sound of the thing that you recorded. It had a certain way of cutting lots of the frequencies off the sound so it was particularly good for basses because it would give you a picture of the bass without all the bottom end in quite a clever way.”

“I think that's why it was so exciting back then because it sort of romanticised the sound. Nowadays sampling is incredibly clear, it's perfect and you've got unlimited RAM. Back then, having 8MB of RAM was a big deal, so you'd have to find ways of making things fit.”

Engineer J.J. Jeczalik, who was a key programmer at the core of the Art of Noise alongside Gary Langan, was a studio hand who first met Horn and Geoff Downes during their time together in Yes. In January 1983, Jeczalik and Langan were working on the Yes album 90125 when they took a discarded loop and sampled it in their Fairlight.

This was the start of their love for the synth. Then after Horn had parted ways with Downes, he decided to invest in his own Fairlight. When he needed some support understanding it, it was Jeczalik who he called.

“The other great thing was that back in 1982 nobody really understood what it did and JJ [Jeczalik, Horn’s Fairlight operator] being a kind of non-musician would constantly sample all kinds of weird things,” said Horn. “Cash registers, drills out on the road and stuff. So to me that was the sort of a ‘golden era’ back then when you were hearing things that you'd never heard before.

“People were always asking me, trying to find out what I was doing because they didn't understand and I never used to tell them.”

Horn’s CV from that golden decade is stuffed with an embarrassment of musical riches with tracks for era-defining auteurs and pop success stories, including Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Pet Shop Boys, Grace Jones and ABC.

Jeczalik was among Horn’s team who worked on the latter’s album, The Lexicon of Love including Anne Dudley who created the string arrangements.

With Langan and Dudley, he was also part of Horn’s production team for Duck Rock, the 1983 album released by British impresario and one-time Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren.

In his autobiography, Adventures in Modern Recording, Horn writes: “I'd tell JJ what I wanted the Fairlight to do and he would work out a way to do it. Sometimes spending weeks working on it. And what that meant was that as the 1980s wore on I was doing stuff with the Fairlight that nobody else had done, and nobody knew how I was doing it. I was the first idiot to get one. Once I understood what it was capable of I'd lie awake at night dreaming up [stuff] for it to do."

While some musicians were using samples as ways of adding splashes of aural colour to their music, Horn and his colleagues saw the potential to craft entire compositions with the sampler.

For this new musical venture, the production team from the Malcolm McLaren album project joined forces with music journalist Paul Morley who had previously interviewed Horn for the NME.

Rather than a musician, Morley’s role was to come up with ideas and concepts, which he named after a 1913 Futurist manifesto. Much of the music was born out of what Horn described as the collective ‘looning around’.

“We used to say, 'Hoist the Jolly Roger! We're coming aboard!' We would sample bits of tracks and throw stuff together. Beat Box, the beginnings of Moments in Love and bizarre things like The Army Now were just me screwing around,” he said. “Paul Morley came up with the name - the Art of Noise - and the name inspired us. He even came up with [song] titles like Moments in Love, and we went on to write the song.”

Amid the concepts and enigmatic sleeve notes, the group were a genuine moment of pop innovation. With no lead singer as a focal point and little detail about who was behind the music, this gave their ideas and technology opportunities to do all the talking while forging a new way for artists to treat their relationships with creativity and fame.

Dudley told MTV: “We're not a conventional pop group. We don't have a singer, we don't have spiky hair or any kind of fashion image, and we don't really record songs."

The debut album, Who’s Afraid of the Art of Noise?, was released in 1984 with Moments in Love, a ten-minute ambient classic, one of the musical jewels in its crown (it also soundtracked Madonna getting married to Sean Penn the following year).

As Jeczalik told the Red Bull Music Academy, this track was one of the many ideas the group came up with using the Fairlight. Dudley shared a recording of an orchestral stab with Jeczalik which he toyed with over a weekend before responding to in the studio the following Monday.

“It started from a sample, it started from a basic melody of mine and then an atmosphere,” he said. “Then we had discussions about what to do with it. I said, ‘Let’s make it the longest, most boring track we can.’”

“It was a bit of a laugh to us, it was a bit of a laugh that we had a lot of nine bar loops in there that people didn’t spot, but enabled us to create the little stop bars here and there. When you put a stop bar in a track it means you can completely rebuild it. Trevor liked his stops, where you clear everything away, and then rebuild.”

When it was released as a single in 1985, on the flip was Beat Box, another track that came from Jeczalik and Gary Langan experimenting.

“We were just goofing around,” said Jeczalik in the same RBMA interview. “We recorded things like finger pops, Gary and I going, ‘err like that’. There’s a sound that goes, ‘yenom’, which is us going ‘money’ and just flipped it round, because it amused me. There’s something interesting when you flip sounds round, or you flip them round halfway, or you do weird things with it. I was doing quite a lot of that at the time, so there’s lots of bits and pieces of the library on there.”

The percussive, cut-up instrumental became a favourite with body-poppers, particularly after Horn played the track to Chris Blackwell at Island Records. Blackwell loved it so much that he took a cassette of it to New York where it was played at the Danceteria. This launched the group in the US and even led to them being named as Best Black Act of the year by Billboard magazine in 1984.

Close (To The Edit) was closely related to Beat Box and named after the fifth studio album by Horn’s previous band, Close to the Edge. Exemplifying their magpie-like approach to collecting sounds and ideas, the single features the recorded sample of a car, a VW Golf owned by a neighbour of band member Jeczalik.

“Gary set about editing it all,” Dudley told the Guardian. “This was back in the day when you had to literally slice tape with a razor blade. We ended up with something quite quirky but we certainly didn’t think it had legs as a single. To our amazement, it got to number eight.”

The original incarnation of the Art of Noise had dissolved by 1985 with Dudley, Jeczalik, and Langan choosing to leave behind Morley, Horn and their ZTT label.

But their influence and legacy lives on, various members have come together to perform tracks from their catalogue utilising today’s technology.

As RA reported, if you’ve ever attended Despacio, the sound system party helmed by James Murphy and Soulwax, then you’ll likely have heard Moments In Love coming through the incredible McIntosh system as the dancefloor warms up. The timelessness of their music and their attitude continues to echo through music culture to this day.

“Daft Punk and Gorillaz have realised our ideas of anonymity and animated performers more fully, and I love to say that we’re the third most sampled group of all time,” Morley told the Guardian. “The proudest for me was the Prodigy on Firestarter. They wanted our 'Hey', the one on Close (to the Edit) - no other would do. The royalties kept me in coffees for many years.”

Jim Ottewill is an author and freelance music journalist with more than a decade of experience writing for the likes of Mixmag, FACT, Resident Advisor, Hyponik, Music Tech and MusicRadar. Alongside journalism, Jim's dalliances in dance music include partying everywhere from cutlery factories in South Yorkshire to warehouses in Portland Oregon. As a distinctly small-time DJ, he's played records to people in a variety of places stretching from Sheffield to Berlin, broadcast on Soho Radio and promoted early gigs from the likes of the Arctic Monkeys and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Art Of Noise - Beat Box (Diversion One) [1984] HQ HD - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/JSWhzsGY3hA/maxresdefault.jpg)