“Before we knew it we had a sound no one had ever heard before”: How David Bowie created one of the greatest songs of all time via a range of innovative recording techniques

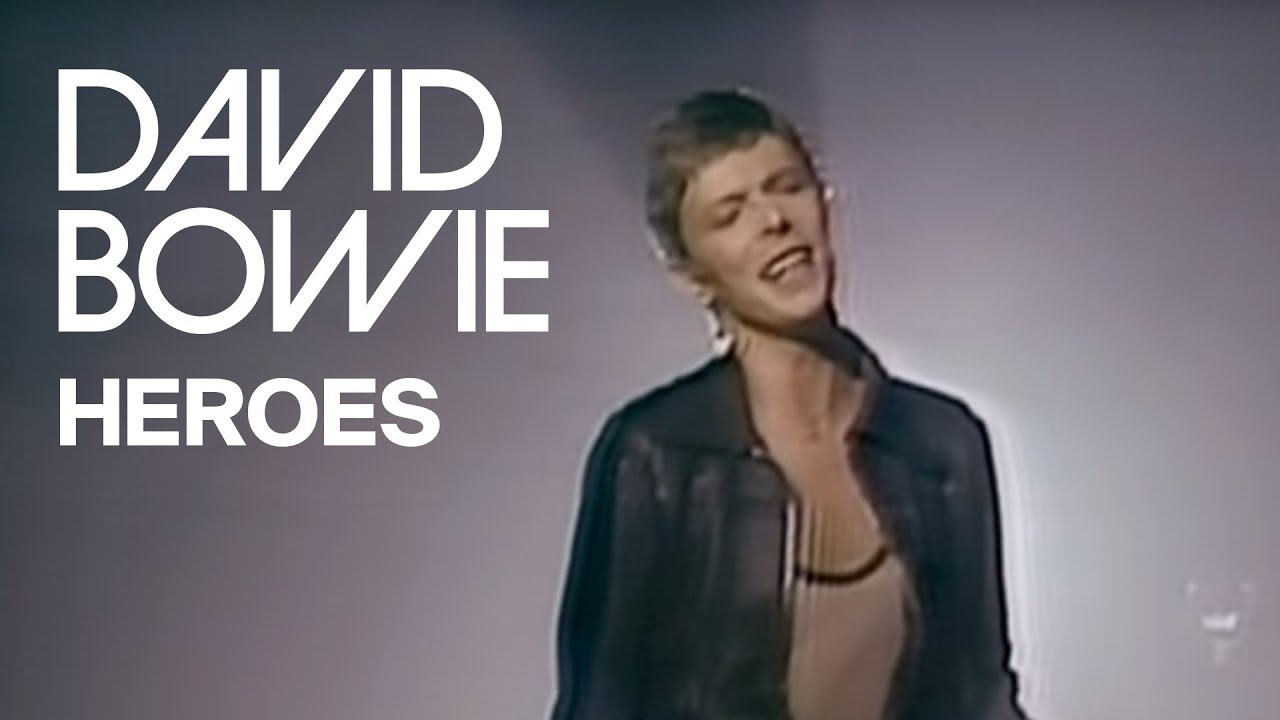

One of Bowie’s highest watermarks, Heroes continues to sound utterly timeless due to its layered production and passionate vocal performance

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

RECORDING WEEK 2025: Nobody would deny that David Bowie was one of music’s most influential pioneers. Yet, while a commonly-held misconception would dub Bowie as pop’s trend-aware ‘chameleon’, some of his most essential work paid little heed to the prevailing musical landscape.

Arguably his finest moment on record (it’s certainly jostling for the top-spot), 1977’s magnificent Heroes genuinely sounded unlike anything before or since, but soon became widely regarded a creative high.

Written at the heart of Bowie’s electronic-leaning Berlin period (and the title track of the second of his ‘Berlin trilogy’ of albums), Heroes was a record enthralled by a city that David had recently begun to call his home, and stirred by the people who lived in the shadow of the imposing Berlin Wall.

At that point in history, the Wall (which wouldn’t fall until 1989) split Berlin between the more liberal West and the Soviet-controlled East. It was a crossroads where two globally-warring ideologies met. A very literal obstacle to peace and progress.

Bowie’s lyric portrayed an honest, human story of love. It was a truthful depiction of a relationship that was flawed, problematic and riven with issues, but pulsing through the hardship, a determination that nothing was insurmountable. Love was worth the struggle.

And you, you can be mean

And I, I'll drink all the time

'Cause we're lovers, and that is a fact

Yes we're lovers, and that is that

Though nothing will keep us together

We could steal time just for one day

We can be heroes for ever and ever

Framed within a nostalgia-triggering - but simultaneously otherworldly-sounding - arrangement, and defined by a towering vocal performance that became fired-up with raw passion, Heroes followed no rulebook.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It could only have been written by David Bowie within the set of very specific circumstances he’d found himself in.

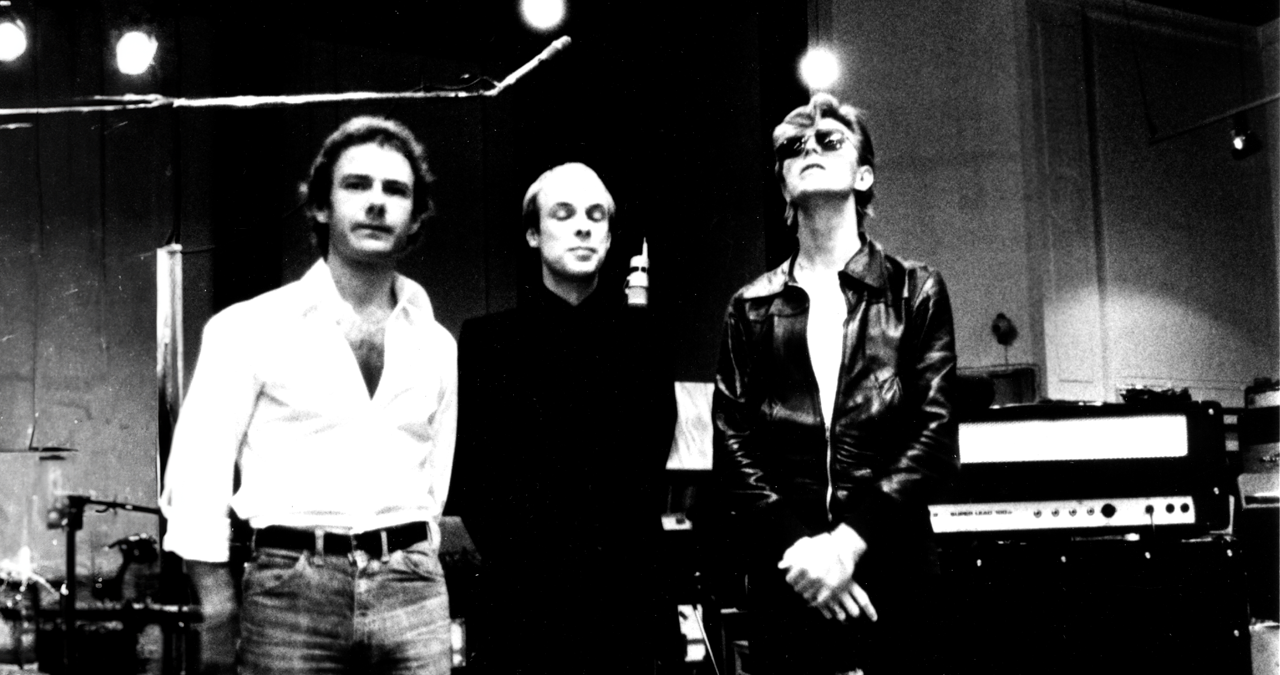

But, bringing the song to life was no solo venture. David was ably assisted every step of the way by the Berlin period’s chief creative accomplice Brian Eno. And, sitting in the producer chair, the ever-inventive Tony Visconti.

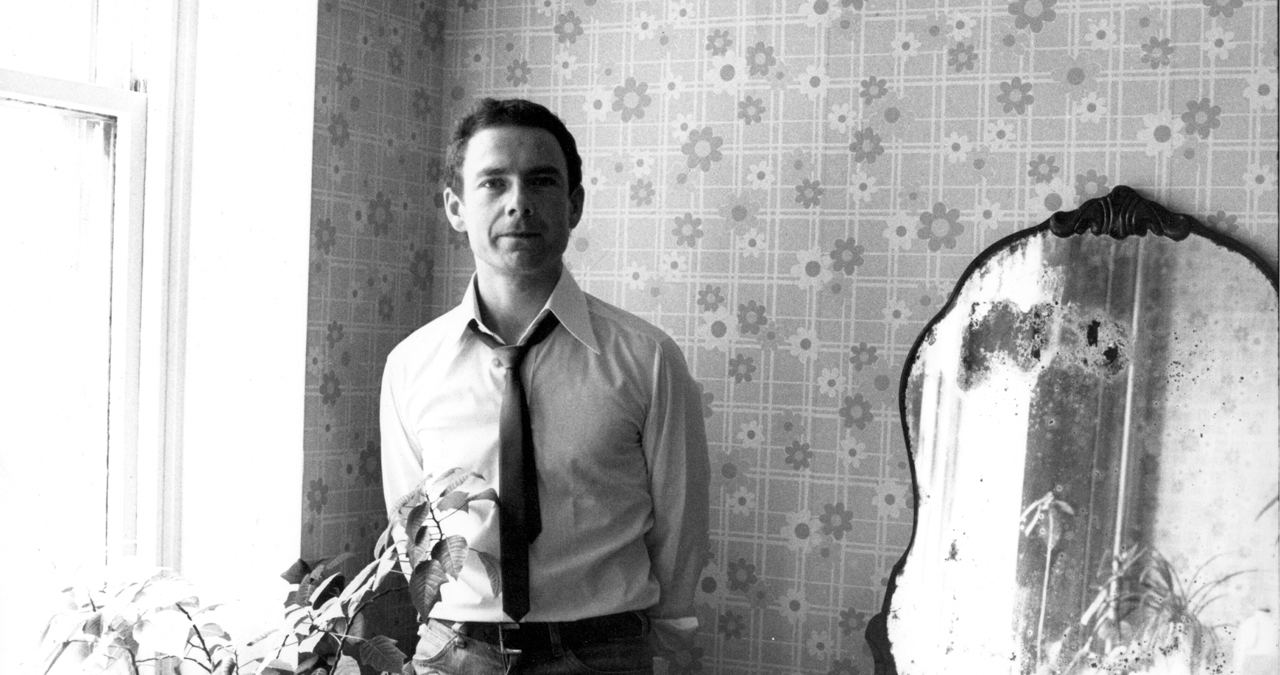

Bowie's longest-serving producer, Visconti had witnessed his friend evolve from young, curly-haired folkster to British pop culture-seizing glam messiah to sharp-suited stateside soul boy. Now Visconti was playing an essential role in making Bowie’s pioneering Berlin ideas a reality.

An analysis of his engineering and production work is crucial to understanding why Heroes works so well.

Although that vocal performance is pivotal, it’s those surrounding musical elements - the ‘chug-a-chug-a’ of the rhythm guitar, the gradual unfurling, throbbing bass and that soaring lead guitar line - that are all fundamental pieces of the jigsaw. All were subsumed into a swirling mix that was a feat of unorthodox experimentation.

But to truly understand the song we have to look at David Bowie in the context of his own journey.

In the wake of massive success with his Ziggy Stardust-era work in Britain in the early 1970s, Bowie managed to skilfully adopt a new persona. Traversing the Atlantic, Bowie delivered quite the most unlikely next step; a US number one single, in the shape of 1975’s slinky, disco-adjacent Fame, co-written with John Lennon. Nobody saw that coming.

With a swelling legion of followers, ready to follow their genre-flitting hero wherever he wanted to hang his proverbial hat, Bowie had become that rarest of things: a questing musician motivated by an irrepressible artistic drive, as well as an ultra-famous, chat-show friendly celebrity.

But, living in Los Angeles in the mid-1970, Bowie had begun to deteriorate mentally and physically. The result of a now quite serious cocaine addiction.

With a crumbling sense of perspective, Bowie was in a harmful spiral of ill health. Getting clean and resetting somewhere else became more than another persona switch-up, it became a matter of life and death.

Musically too, Bowie was feeling a strong pull toward Europe, and its fascinating new tranche of German electronic acts such as Kraftwerk, Neu! and Can. It seemed that this was where the real innovation was taking place.

“Towards the end of my stay in America, I realised that what I had to do was to experiment. To discover new forms of writing. To evolve, in fact, a new musical language. That's what I set out to do. That's why I returned to Europe,” Bowie told Melody Maker in 1977.

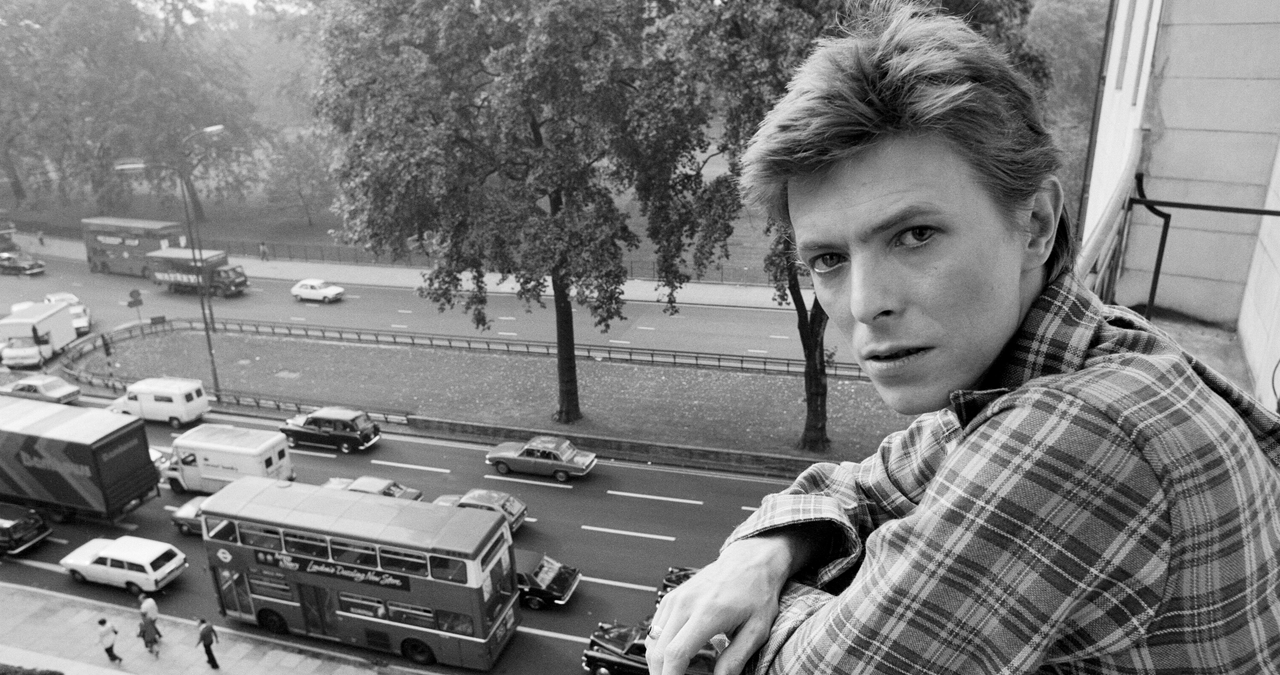

Berlin seemed a particularly inviting retreat from the intensity of LA, “For many years Berlin had appealed to me as a sort of sanctuary-like situation,” Bowie told Uncut magazine. “It was one of the few cities where I could move around in virtual anonymity. I was going broke; it was cheap to live. For some reason, Berliners just didn't care. Well, not about an English rock singer anyway.”

Surprisingly, the first record in what would be dubbed the ‘Berlin’ trilogy, Bowie’s 1977 gem Low, was actually largely recorded at the Château d'Hérouville in France during a period when Bowie was living in Switzerland, before having the finishing touches of the album applied at Berlin’s Hansa Studios.

Along with his good friend Iggy Pop (who was facing his own similar drug and mental health issues) Bowie fully decamped to Berlin.

In Berlin, the former Thin White Duke undertook a rapidfire whirlwind of creative projects.

With the first record in a new series of pioneering records under his belt, Bowie took on a mentoring role with Pop, pushing his new solo career via his two trailblazing albums, The Idiot and Lust for Life (more on that here, including Bowie’s role as Iggy’s touring keyboardist). But, Heroes would be the only completely Berlin-centred album in Bowie’s trilogy (the third instalment, Lodger would be recorded between Switzerland and New York.)

With their shared flat in Berlin as their base, Bowie and Iggy fully immersed themselves into their new identities as Berliners. Taking up nightly residence in several bars, the duo found themselves absorbed by the city’s vibrant culture.

Living and meeting the city’s denizens, Bowie was struck by the omnipresence of the Wall, and how it served as a living reminder of the city’s dark history.

Perhaps it was for this reason why Bowie chose Hansa Studios' largest room, Studio 2 (formerly the historic concert hall Meistersaal) to principally record the new album.

Hansa was situated extremely close to the Wall. It could be clearly seen from several windows, as could its unnervingly gun-toting border guards.

Its shadow, Bowie surely felt, would therefore be cast on the record. It was a sense of time and place underlined by the huge natural reverb of the massive space in which he had set-up.

As with the preceding album, Bowie decided that the first half would consist of fragmented songs while side two would be an instrumental suite with minimal vocals (save for the album’s finale, The Secret Life of Arabia). Among the glut of new Berlin-inspired cuts Bowie brought to the table was the title track.

Musically, Heroes was built around a pulsing chord swing between D and G major. Lacking a conventional ‘chorus’ as such, instead the verses led to a more embellished chord sequence, that swung to a vibrant C, then back to the pulse of D before reaching for an emotive Am and Em, before - once again - being magnetised back to the safety of D.

The triumphant, verse-sealing motif of ‘We can be heroes, just for one day’ was spelled out by the punctuation of C, G and D major chords. Ad infinitum.

Simple but beautifully effective, you really could listen to the warm embrace of this cycle forever.

In an expeditious system first devised during the recording of Low, Bowie’s core band - rhythm guitarist Carlos Alomar (who’d first joined Bowie during the Young Americans sessions in mid-1974, and would go on to be his longest serving guitarist) drummer Dennis Davis and bassist George Murray - (aka the D.A.M. Trio) would record their basic instrumental tracks live in the studio in only a handful of takes quickly after learning the song. These raw band passes would be used as a foundation to built upon later.

Murray was confounded however when he got the studio on the first day of recording for the new album, only to discover that the band’s instruments hadn’t arrived yet. “In fact when we walked into the studio in Berlin to do Heroes our regular equipment hadn't made it,” Murray told Sound International the following year. “So we just had to see what we could find lying around the studio. They had this weird amp that I used, I don't know what it was.”

“We always started these albums as making demos,” Visconti told Uncut. “Then we'd realise that the ‘demos’ needed just a little editing without re-recording. Sometimes I would take a great section and copy it and edit it into the song later on, cutting right across the 24-track tape. I wouldn't say they were first takes, we worked hard and long on each track. We didn't go into say 25 takes, but I'd say that most tracks were done in about 5 takes.”

With a basic rock and roll groove that harked back to the passive garage aesthetics of The Velvet Underground, the foundation of Heroes’ music bore little resemblance to the sonic maelstrom it would become, but key arrangement components were hit upon during those first runs by the band.

“The underlying riff on Heroes was Carlos's idea,” Visconti told Sound on Sound. “As was the pre-chorus part, which is like a viola and cello section. David's modus operandi would be to throw a bunch of chord changes and a bunch of ideas in a very loose structure at the band, and he knew he could rely on those guys to immediately do something. They were jam experts, and so within half an hour they would jam the few chords that David threw at them into a wonderful structure.”

Alomar recollected to our sister site Guitar World last year that tracking Heroes was a memorable experience. “That song was like riding a wave… a sonic wave. It just had a beautiful drone that we didn’t want to disturb. My approach was to keep the guitar parts simple yet powerful, allowing David’s vocals and the overall production to shine.”

Bowie’s collaborator and veritable synth pioneer Brian Eno could sense that this ‘heroric’-sounding track could be elevated into a new dimension via the application of some typically freewheeling synthesised colouration and processing.

Over the course of a week, the overdubs began with Eno’s briefcase-housed EMS Synthi AKS. Eno layered a rippling eddy of electronic current which floated amid the frequency spectrum of the track, shimmering beautifully in the spaces between the live instruments. It was the thrum of Berlin’s indomitable spirit made sound.

Using the first of the synth’s three oscillators, Eno rode the noise filter and gradually adjusted the rate and speed, making the track appear to shudder. Its presence would be almost subliminal, but was imperative in making Heroes' resonate deep.

“[Eno] really isn't a musician as much as he is a technician and an ideas man,” Dennis Davis told Sound International, “He hasn't got super chops, he's got a super concept of controlling and operating synthesisers.”

Robert Fripp, lead guitarist of prog trailblazers King Crimson (then on hiatus) and a longtime friend and collaborator of Brian Eno, was called upon to undertake lead duties for the album.

It was Fripp that performed the soaring, feedback-driven guitar line that was woven throughout the track. Astoundingly, it was a line that was semi-improvised.

Fripp had mastered wrangling pitched feedback and manipulating it creatively via maintaining a specific distance from his amplifier. As recounted By Visconti in Thomas Jerome Sandbrook’s excellent book, Bowie in Berlin, “He had a strip that he would place on the floor, which showed him where he needed to stand to produce each note.”

The results were live processed via Brian’s EMS Synthi, who used the synth’s joystick to wring and stretch the incoming signal in real-time. After four passes, Visconti enmeshed the takes together to form a composite mix.

“Fripp is AMAZING!,” Visconti told Uncut magazine. “He did his Frippatronics thing and plugged into Eno's EMS briefcase synth. The combination was terrific. His playing on Heroes didn't take long. He just played one pass and asked for three more tracks to embellish the first take. Before we knew it we had a sound no one had ever heard before. The guitars on that track are breathtaking.”

Upon hearing what Fripp, Eno and Visconti had brewed, the prevailing theme of this (at that stage) lyric-less piece began to crystallise for Bowie.

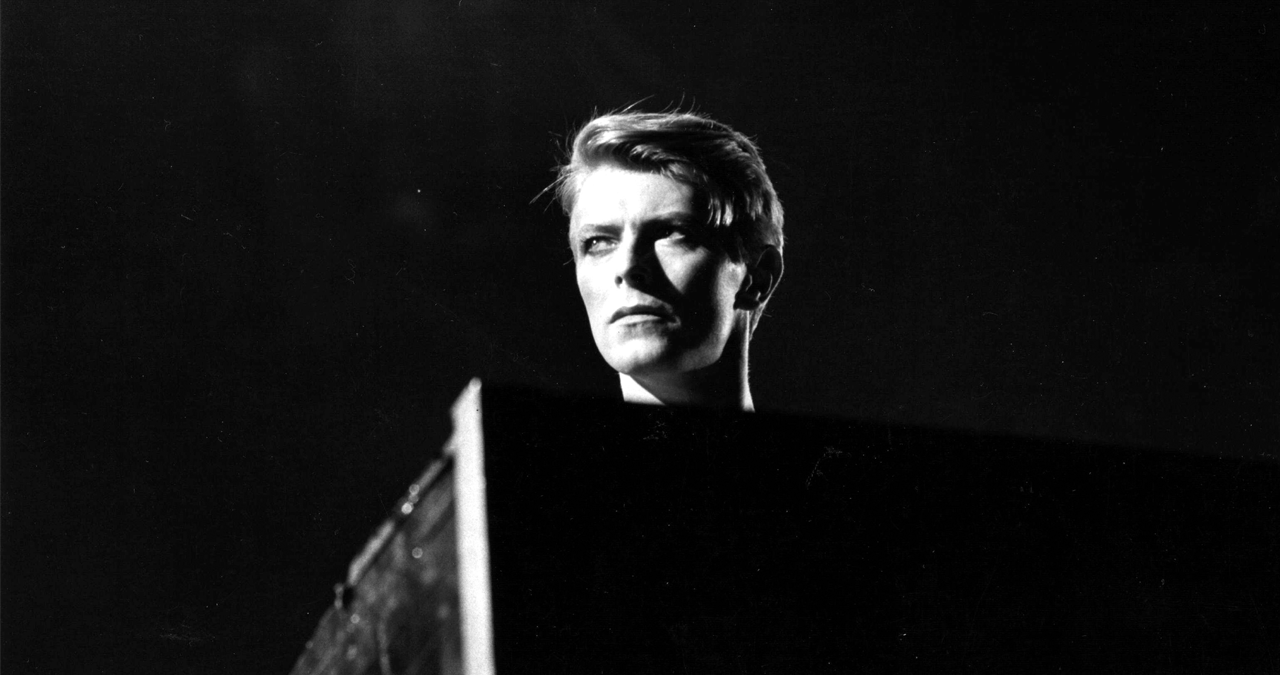

“Fripp’s plaintive guitar cry really triggered off something emotive in me,” Bowie recollected in an archival interview in the BBC Documentary Five Years. “It was a song of triumph. It was like, ‘I’ve been a real idiot some of my life and put myself in ridiculously dangerous situations, and I’ve seemed to get through it.’ That became part and parcel to that song: that you can overcome some incredible odds.”

Further augmentation came via Bowie’s (rather naff-sounding) synth brass, constructed with his Mellotron-like Chamberlain. Subsumed into the mix, this synth brass subtly added the sense of a classical hero's exultant return, while an ARP Solina was also deployed to paint in some higher-pitched leads.

Additional unorthodox rhythmic embellishment came when the pursuit of a cowbell turned up nothing - and the thwanging of an empty tape canister had to suffice.

Visconti approached shaping the mix with his ears open, and the rulebook firmly closed.

Realising that the kick drum wasn’t adding to the mix, Tony reduced its presence dramatically. This had the effect of bringing the bass - which had already been infused with an MXR flanger when committed to tape - into a more prominent supporting role.

Unmoored from the central pilar of a kick, Heroes now felt as if it floated in mid-air. It was becoming something wholly unique production-wise.

Editing the track was another skill for which Visconti was a master. Recorded onto 24-track tape, Visconti had to carefully snip and move parts around with delicacy and precision.

“It was dangerous living, because you couldn't do too many edits on the same point without the tape starting to curl up or the backing coming off,” Visconti told Sound on Sound. “You had a maximum of, say, two edits that you could do and undo in the same area, but we firmly believed that if you didn't do it, it wouldn't be worth keeping the track anyway. So, living dangerously wasn't that dangerous really."

On Low, Visconti had (famously) been overly-enamoured by the Eventide Harmonizer, applying it to all the live drums of that record. But, for Heroes he opted to leave it on the shelf. The sound of the kit within the gargantuan Studio 2, it was felt, was characterful enough.

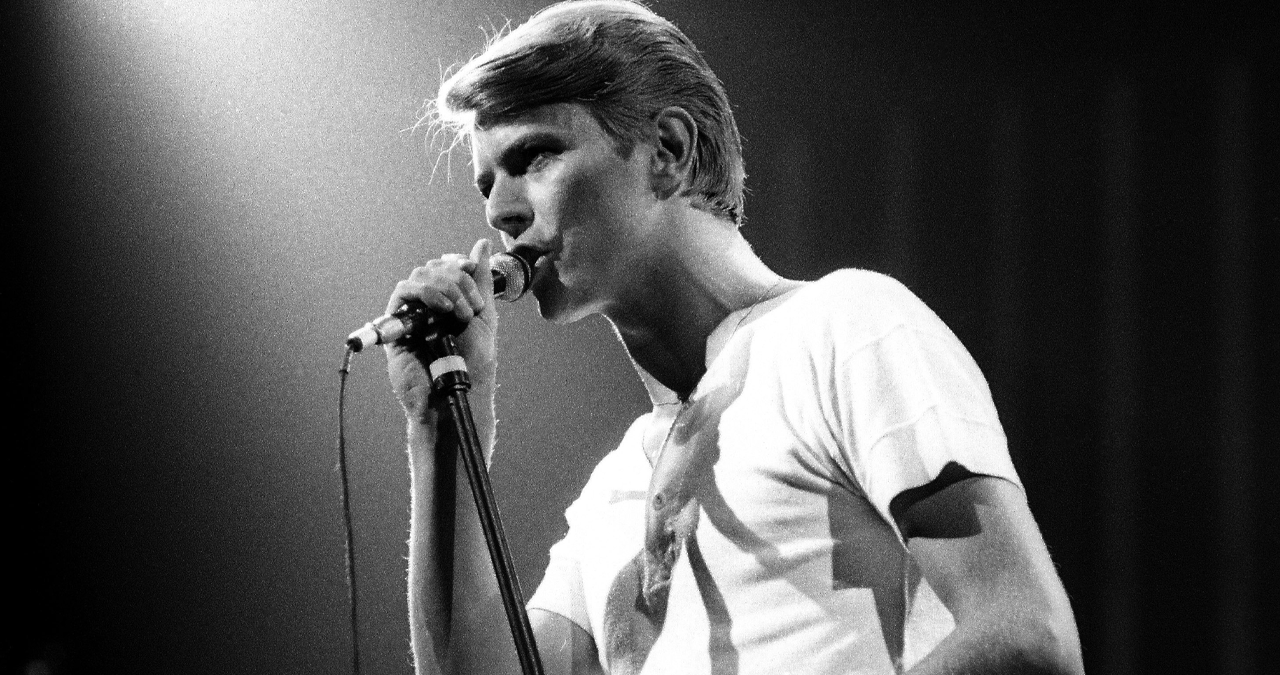

Although the mix was an exceptional feat of sound engineering, it’s really Bowie’s impassioned vocal performance that remains the track’s most scintillating moment. Again, realising it was a feat of unorthodox engineering.

Bowie’s central lyrical inspiration, concealed for many years after the song was written for understandable reasons, was his aforementioned producer.

As Tony Visconti himself has latterly recounted, he was, at that moment in time, having a clandestine relationship with German singer Antonia Maass. Unbeknownst to his then wife, Mary Hopkin.

It was out of the window of the studio that Bowie observed his old friend locked in an illicit embrace with Antonia, kissing her beneath the Wall.

The impossibility of the secret relationship, underlined by the looming monument to oppression, chimed with Bowie.

To David, Tony and Antonia's kiss was a vision of a small triumph. Unbowed humanity in the face of all obstacles. Whether they be existing marriage vows or physical barriers, patrolled by border guards.

I can remember

Standing, by the Wall

And the guns, shot above our heads

And we kissed, as though nothing could fall

Bowie recounted a veiled version of what he’d witnessed to NME later that year, when explaining what influenced the songwriting. “They were obviously having an affair. And I thought of all the places to meet in Berlin, why pick a bench underneath a guard turret on the Wall? They’d come from different directions and always meet there. I presumed that they were feeling somewhat guilty about this affair and so they had imposed this restriction on themselves, thereby giving themselves an excuse for their heroic act. I used this as a basis.”

With his hurriedly-penned lyric written shortly before the recording of the vocal (which also, as Bowie later revealed, alluded to Alberto Denti di Pirajno’s A Grave for a Dolphin) David geared up to deliver the vocal of his life.

To capture Bowie’s vocal - which would gradually rise in intensity and volume as the track progressed - Visconti set up three Neumann mics within Studio 2.

The first of which was a valve U 47 placed directly in front of Bowie. This was heavily compressed. The second, Visconti’s ‘Swiss army knife’ microphone, a Neumann U 87 was between 15-20 feet from Bowie. The final piece of the circuit was another U 87 at the far end of the room, around 50 feet away. Ready and waiting for Bowie to give it his all.

The U 87s wouldn’t activate until a certain decibel threshold was reached (controlled by Bowie’s vocal levels as the song progressed) and thus, once Bowie began to get loud, Visconti’s noise gate would open and capture his voice reverberating around the room. It had the effect of flash-burning this specific moment in time and space onto the track, forever.

This noise gate system required that Bowie maintained an extreme volume level to keep that final U 87 activated, which goes some way to explaining why he’s so histrionic by the concluding verse.

“Bowie was thrilled with the idea that I wanted to do something unique. He thrives on anything that's different and someone else hasn't thought of yet,” Tony recounted to Sound on Sound.

After three eye-wateringly brilliant takes, Bowie and Visconti had achieved something staggeringly impressive. Once a series of backing vocals were quickly taped by the pair, the vocal recording process was completed. It took just five hours in all to capture one of the most affecting vocals in music history.

“What is really great is that the sound of the opening two verses is really intimate. It doesn't sound like a big room yet, it sounds like somebody just singing about a foot away from your ear,” Visconti recalled in his interview with Sound on Sound.

“The whole idea worked, and what you hear on the record is probably take three. We wouldn't go beyond that. He was really worked up by then and I can tell you he was feeling it. It was quite an emotional song for him to sing.”

Released as the record’s lead single on September 23rd 1977, Heroes (stylised with quotation marks as “Heroes”) was, for some, a clearly brilliant piece of work, and an obvious masterpiece.

For other contemporary listeners, it was baffling. This was borne out by the song only reaching number 24 in the UK and not even charting at all in the US.

However the majesty of Heroes would soon be recognised by everybody, with the song becoming widely acknowledged as one of the greatest of the decade - if not the century.

"I'm afraid I am pessimistic", the late legend told Melody Maker upon this seemingly optimistic-sounding record’s release. "I'm not at all optimistic about the future. But I'm totally resigned to the situation. There is, I hope, some relief in compassion - and I know that's not a word usually flung at my work - and Heroes is, I hope, compassionate. Compassionate for people and the silly desperate situation they've got themselves into. That we've all got ourselves into.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores the inner-workings of how music is made and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for a range of titles including NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.