“I just had to sit there, drink a bit, have a cigarette, wink at the band”: Why David Bowie ditched promoting Low and instead became Iggy Pop’s keyboard player

Bowie put helping his Berlin flatmate Iggy Pop first, with promo for one of his greatest ever albums falling by the wayside

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

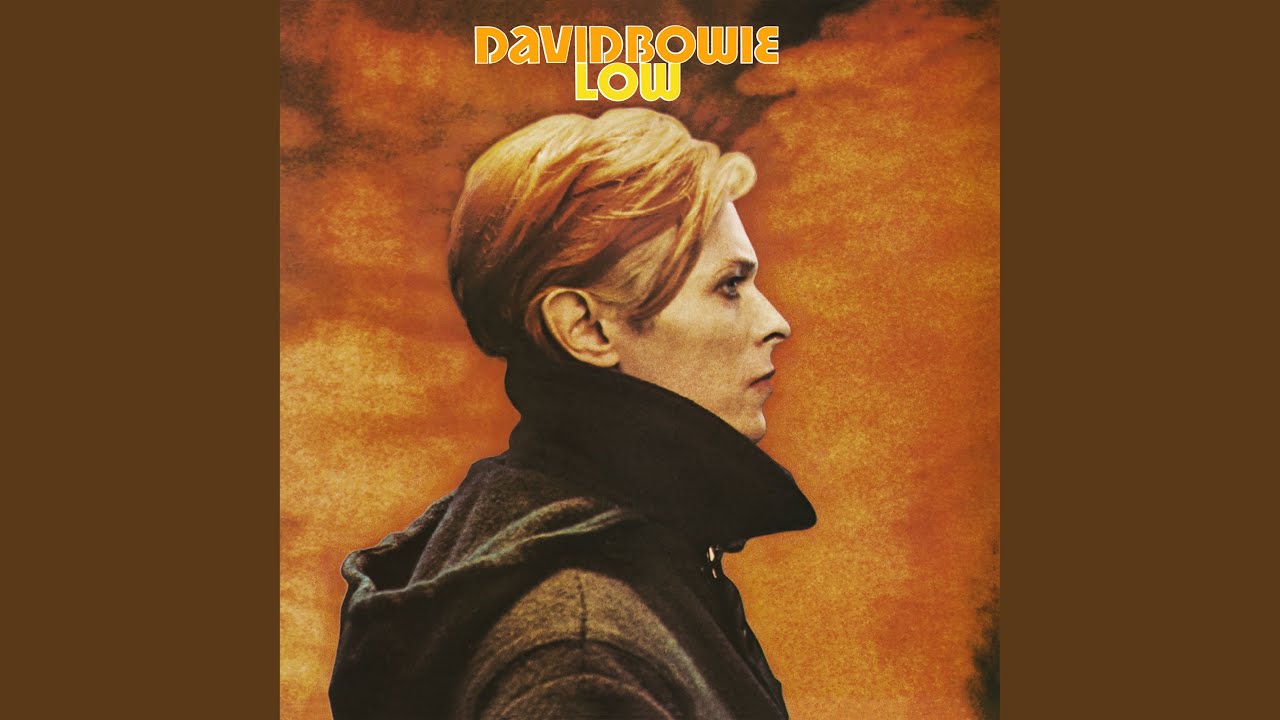

For a large proportion of his devotees, 1977’s Low sits at the (or somewhere very near the) pinnacle of David Bowie’s recorded output. The first entry in his revered ‘Berlin’ trilogy, Low found Bowie and trailblazing collaborator Brian Eno embarking upon a veritable odyssey of sound via an array of then state-of-the-art synths.

Split into two distinct halves, Low’s more conventional A-side was defined by a scattershot assortment of taut, full-band vignettes, interspersed with a handful of some of Bowie’s most glimmering gems of the decade (Sound and Vision, Always Crashing in the Same Car, Be My Wife).

But it was the album’s cutting edge, largely vocal-free second side, that blew most contemporary listeners away. Purposefully sequenced to run as a standalone listening experience, the mountainous, synthesized terrain marked a significant artistic leap. But it was a commercial and critical gamble.

Already established as an artist prepared to take risks (see 1975’s plastic soul pivot, Young Americans for a particularly successful example), sacrificing an entire half of an anticipated new LP to what was feared would be deemed as pretentious, avant garde experimentalism was undoubtedly Bowie's boldest step yet.

Hindsight has, of course, proved that Bowie, Eno and underrated producer, Tony Visconti's record was a brilliant feat, and a hugely prophetic signifier of the future of music.

But Bowie's label RCA, and the man himself, were both more than a little unsure as to whether the outré Low would prove to be kryptonite to the record-buying public.

“Frankly, it needs more work” was an alleged quote from an RCA insider published in Circus Magazine at the time. Hardly the fulsome backing that Bowie might have expected from a label that had profited significantly from his ongoing purple patch.

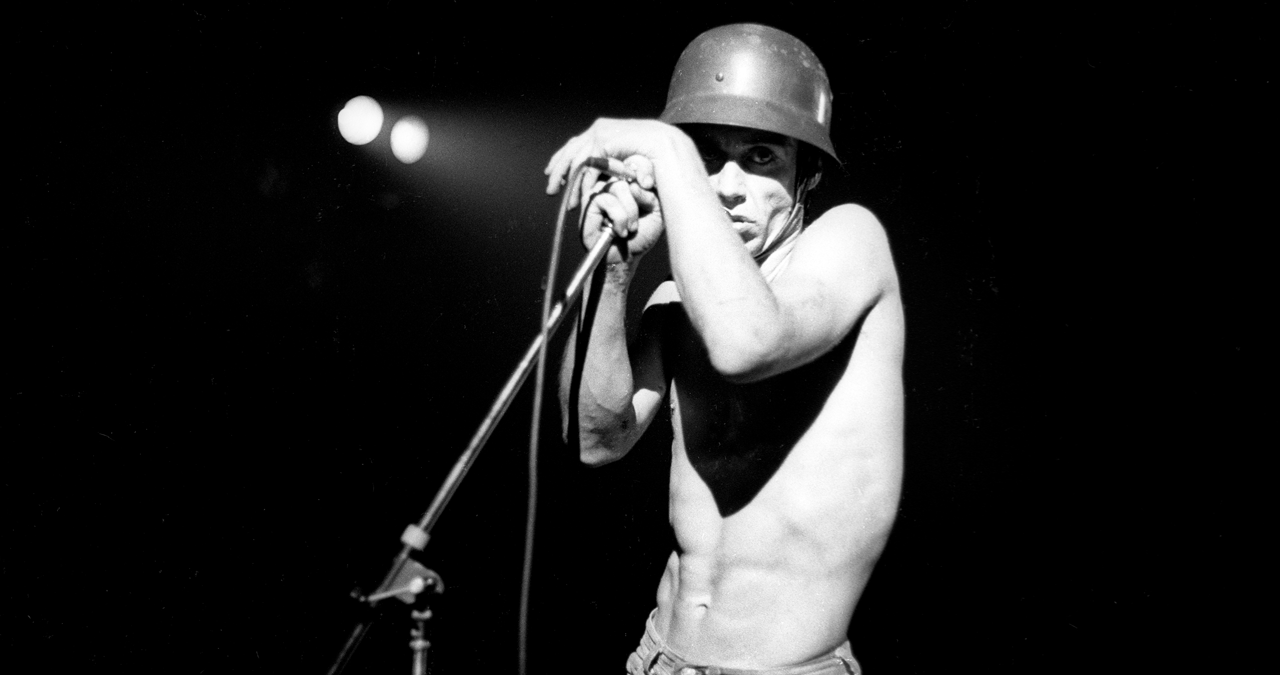

Prior to recording Low, in the summer of 1976 Bowie had co-written and produced Iggy Pop’s iconic first solo album, The Idiot.

The project to develop Iggy into a more left-field, slightly gothic figure would spawn such enduring cultural currency as Nightclubbing, Sister Midnight and future Bowie hit China Girl.

An attempt at revitalising Iggy's creative and commercial fortunes, the Idiot's atmospheric tone would also prove to be an ominous, monochrome harbinger of what would follow in the wake of the then-current technicolor punk explosion. A movement that was, in part (in the UK especially, with its myriad larger-than-life characters) inspired by Bowie’s own glam rock period.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Balancing the eerie and the exhilarating, the dank but exuberant record was just one of many masterstrokes that Bowie orchestrated during this period.

Forming a deep friendship with Iggy (real name James Osterberg) after moving to Berlin in a joint effort to kick their respective drug addictions, Bowie’s aim was to assist the former Stooges frontman in not just finding a new direction as a musician, but as a human being.

Living together in Schöneberg, West Berlin, the pair were inseparable. Ziggy and Iggy.

“He resurrected me,” Iggy said in the wake of Bowie’s passing in 2016. “A lot of people were curious about me, but only he was the one who had enough truly in common with me, and who actually really liked what I did and could get on board with it, and who also had decent enough intentions to help me out. He did a good thing.”

Although Bowie’s Low was recorded after The Idiot, it was released before - on January 17th, whereas The Idiot finally landed on shelves on March 18th. The long gap between its recording and release was down to RCA fearing that Bowie's esoteric electronic ventures had infected too much of The Idiot as well. The record was held back.

Partly out of trepidation around how Low might be received, and also keen to resume his efforts to re-shape Iggy, Bowie elected to spend the intervening gap between the releases keeping a suitably apt low profile.

Enjoying the Berlin scene and spending more time with Iggy, Bowie made the choice to shift his focus entirely onto his flatmate's career.

Low would have to find its own way, with zero live dates and the bare minimum of promotion.

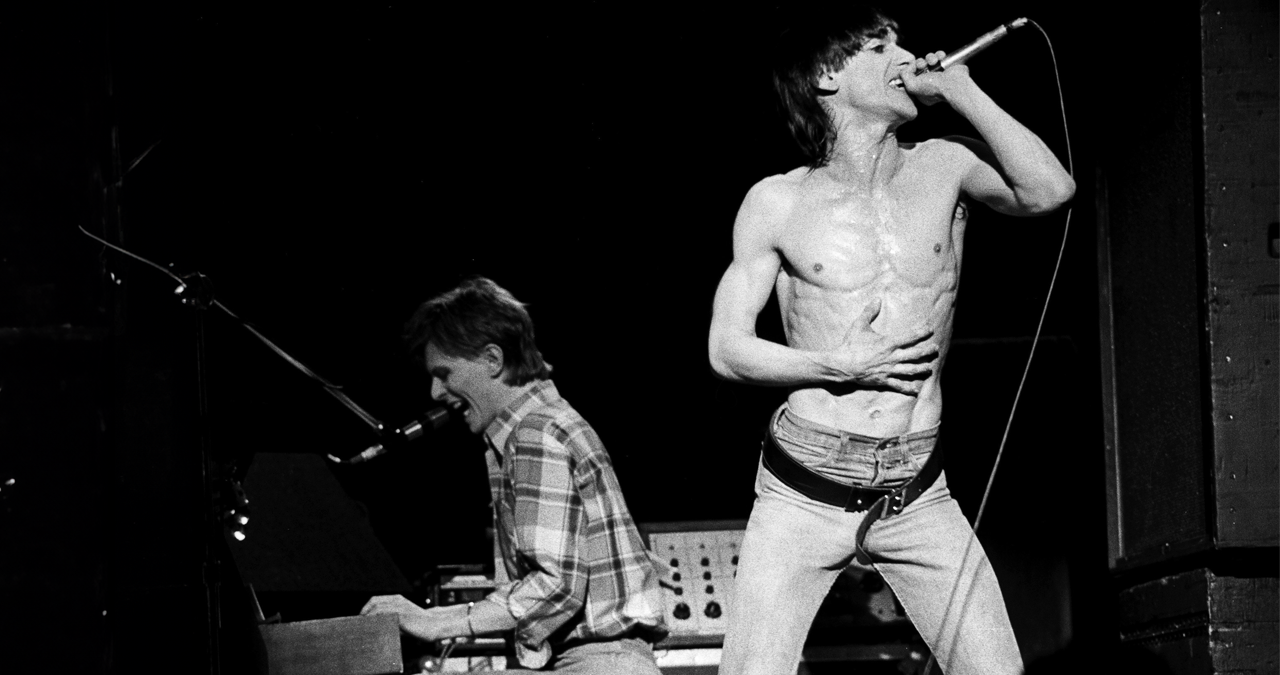

Bowie and Iggy knew that an album launch tour for The Idiot was going to be critical for reinvigorating and building Iggy’s audience, and so Bowie corralled the players.

A no-brainer was Ricky Gardiner. The impressive guitarist had furnished Low with some of its most luminous moments, and David knew that he had the stamina to endure being on the road with Pop.

Meanwhile, the rhythm section was made up of Hunt and Tony Fox Sales. The two brothers (and sons of iconic comedian Soupy Sales) had befriended Bowie in New York a few years prior

Coming as a pair on drums and bass respectively, the Sales brothers' attitude was refreshingly light-hearted and good natured as the nascent line-up convened for rehearsals at a former film studio in the Berlin district of Bablesberg.

In the late eighties, Bowie would hit up the brothers again when forming his infamous alternative rock band Tin Machine.

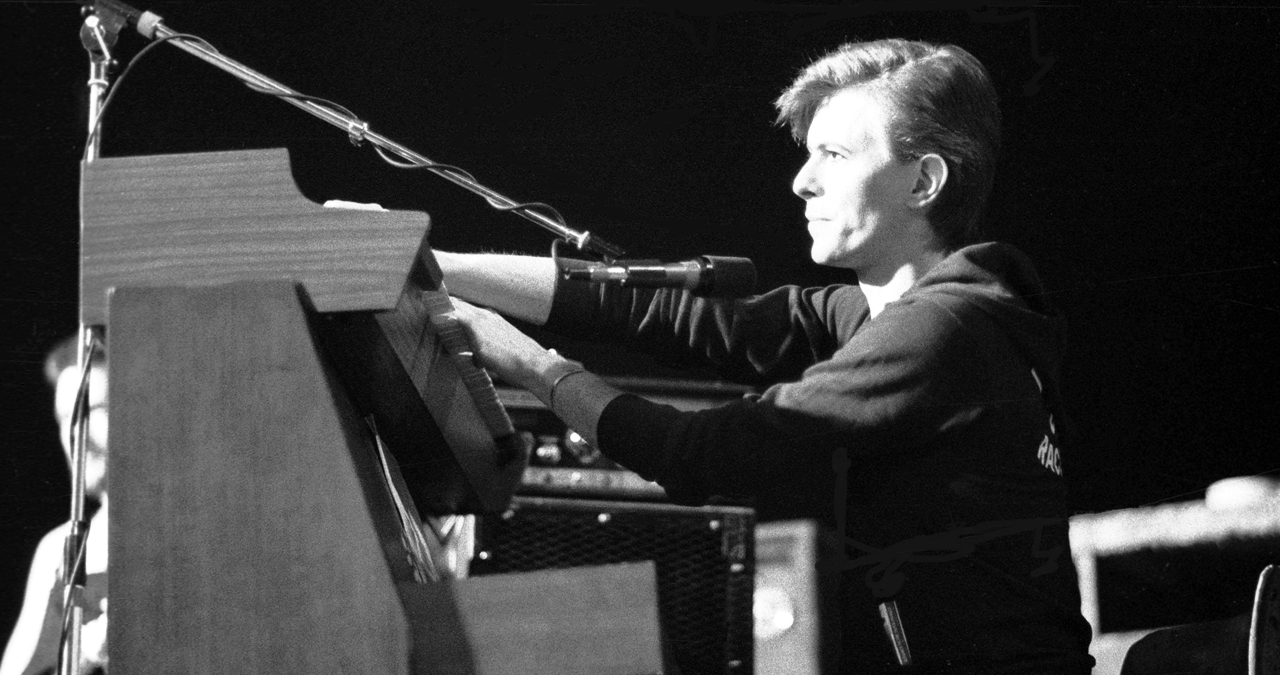

Bowie himself completed the line-up, ostensibly handling keyboards (namely an ARP Solina synthesizer and Hohner Electra piano) but also fulfilling the role of what we’d now dub a ‘musical director’ for Iggy’s new live vehicle.

Bowie had wanted to let it be known that he was Iggy’s artistic patron - characteristically funnelling his audience towards somebody whom he felt needed some of the same rapt attention that he was used to. But at the same time, he didn’t want to pull any focus when playing. He purposefully kept himself obscured off to the side of the stage (where possible).

He was both there, but not there.

The six-week tour began in advance of The Idiot’s release, kicking off at the Friar’s Club, Aylesbury (UK) on March 1st. Fittingly, it was this venue where some five years prior Bowie had delivered near-namesake Ziggy Stardust’s first live foray. But by now, the stereotypical 'gobbing' (i.e. spitting) British punk had started to become a common presence at live gigs. Keen to witness the alleged 'Godfather' of their tribe, they were out in force that night.

It was, according to Ricky Gardiner in an interview on The Stooges forum, a riotous event. "Because the gig was a small club, allowing a close proximity with the audience, there were young males behaving [badly - and spitting]. I must congratulate Iggy for being a true professional and smiling his way through that gig."

The worst was over, and the ensuing tour was much less calamitous. It would span a further five dates in the UK, heading to Birmingham, Newcastle, Manchester and two nights at London’s Rainbow Theatre before heading over to Canada for a couple of dates in Montreal and Toronto, before hitting the United States for a 17-date jaunt.

After a brief return to Canada for one night in Vancouver Gardens, a final lap across the US for four dates, culminated at San Diego’s Civic Auditorium.

“[David] was really disciplined,” Iggy remembered in an interview with the New York Times. “That was at a time when it might be 700 people in Albuquerque, it might be 15,000 at the Garden, it might be 300 people in Zurich, etc. He did a great show every night. I don’t care where it was.”

After the creative intensity of the previous six months, Bowie was happy to take a back seat during the tour. “I never enjoyed a tour so much,” Bowie recalled in ZigZag magazine. “Because I had no responsibilities. I just had to sit there, drink a bit, have a cigarette, wink at the band…”

Despite Bowie’s avoidance of the limelight, it was obvious that a vast swathe of the tour’s audiences had come solely to witness their former leper messiah in the flesh. The Iggy shows had become a draw for Bowie fans particularly as no tour dates for Low had been forthcoming.

It was something that frontman of Iggy’s support for the UK leg of the tour, The Vibrators, definitely observed as he glanced out at the evenings’ crowds. He’d later tell Bowie biographer Thomas Jerome Seabrook (in his superb book, Bowie in Berlin) that there was, “about a 50/50 split [between Bowie and Iggy fans]”, with some even dressed as Aladdin Sane.

Bowie himself though, was transfixed by his friend's complete mastery of the stage. “I’d never seen him onstage up until then,” David told Mojo in 2002. “I couldn’t get over his energy and commitment to savage realism.”

Despite his distance from it, Low had surprisingly done the business.

Steadfast in spite of no direct promotional media appearances or live dates around its launch, lead single Sound and Vision had blasted its way to number three in the British singles chart (likely helped by its featuring in contemporary BBC television adverts).

At this stage, Bowie’s aficionados were clearly with Bowie wherever he opted to go, and Low itself mirrored Sound and Vision with a number three placement in the UK album charts. It even managed to ascend to number 11 in the US charts.

This was a wholly unexpected turn of events, particularly for the dumbfounded (but delighted) RCA executives.

As the tour neared its end, Bowie and Iggy both incongruously appeared on the American family-friendly Dinah! show.

The daytime chatshow was an unexpected promotional choice but was typical of the pigeon-hole denying-direction of David Bowie. After all, it was the end of this very year when a peak-Berlin period Bowie duetted with legendary crooner Bing Crosby for that bizarre Christmas staple, Little Drummer Boy/Peace On Earth.

On the Dinah! show, Iggy was introduced by the show’s wholesome host Dinah Shore as, “the originator of what is called punk rock today,” before being quizzed about his his more violent, Stooges-era stage antics. This line of questioning touched on the infamous on-stage cutting of himself with a broken bottle. “I’ve had treatment for that sort of thing,” reassured Iggy.

The band then tore through The Idiot highlights Funtime and Sister Midnight. The full, surreal thing can be watched below.

His work with Iggy on The Idiot and its live tour was the latest in a chain of astute moves for Bowie. And, for Iggy Pop, it was the creative (and career) rejuvenation he’d sought.

For Bowie it was a way of engaging himself with the then ubiquitous punk scene without making any obvious, awkward moves into it himself.

It re-asserted his status within the punk circle as a still-active progenitor. All the while, his own truly groundbreaking music was making entirely different kinds of waves. Low would prefigure the looming dominance of synth-pop a few years on, and still stands as one of Bowie's most rewarding listens.

Following the tour, the pair reconvened to work on Pop’s follow-up, the more lithe Lust for Life. It was this album which sported the Trainspotting-soundtracking title track, as well as perhaps Pop’s most celebrated cut, The Passenger.

Bowie of course, continued on his own journey, with the second part of his 'Berlin' trilogy. The sublime "Heroes" was released at the end of the year, and its career-highlight title-track was one of the best things anybody made in that entire decade.

A hugely productive period, then. But, back in March and April of 1977, for a brief spell, Bowie was an ocean of calm as he retreated from the spotlight and guided his ferocious friend back to rude creative health.

As Ian Carnochan remembered in his interview with Bowie biographer Thomas Jerome Seabrook, “[He was just the keyboard player]. I think he very much liked not being the centre of attention - it was like he was on holiday.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.