“I lay on my floor one night and wrote the whole thing": 40 years on – the making of West End Girls

From Lake Geneva to the Finland Station… Here's all the ups, downs, history, mystery, studio secrets and more of Pet Shop Boys' biggest hit

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

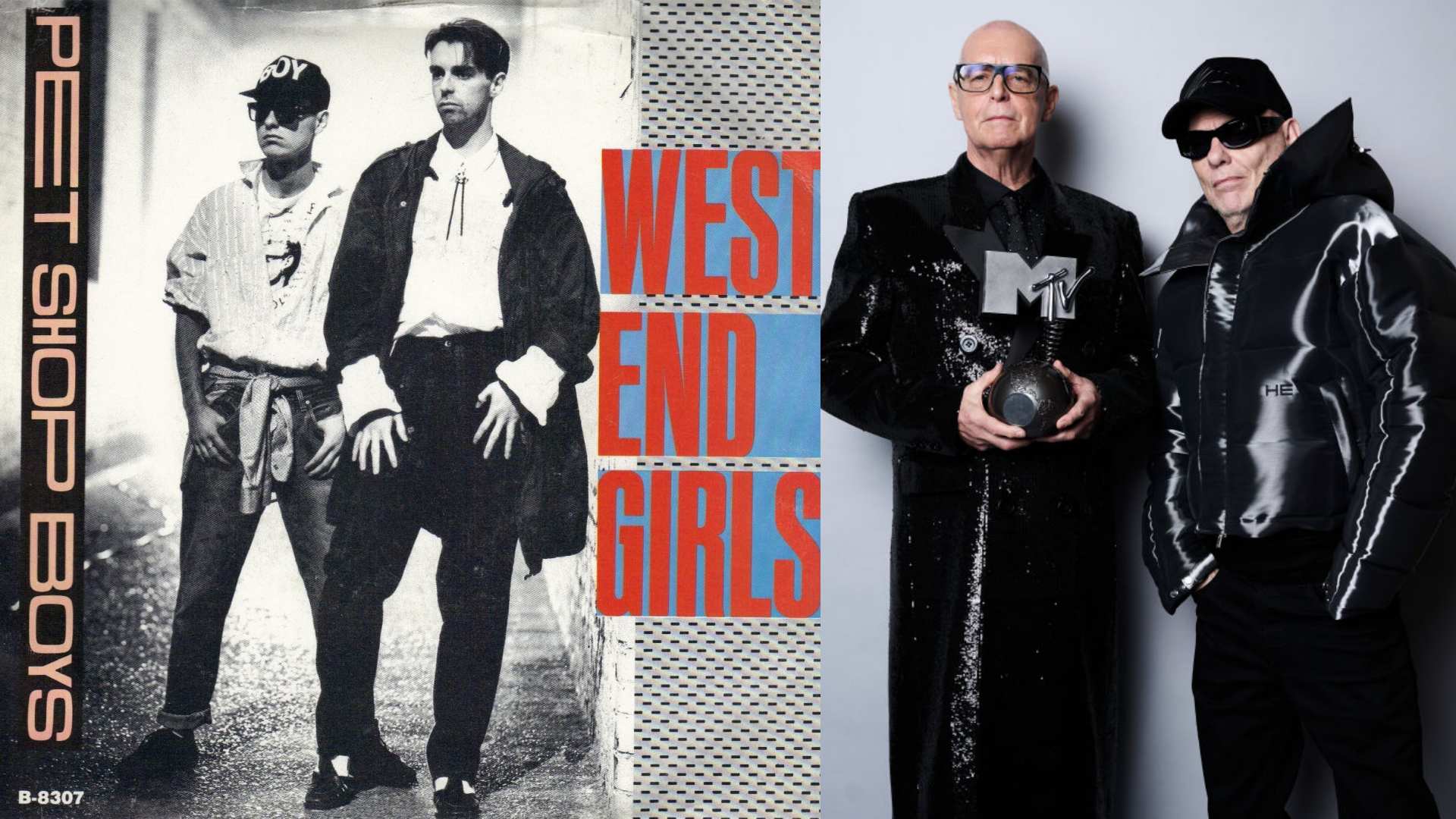

It’s the debut hit that launched a multi-decade career. A track that’s testament to a band’s tenacity, talent and more than a little right time/right place, good old-fashioned good luck. It’s spawned multiple unlikely cover versions. It's The Guardian’s greatest UK number one ever. And it reached number one in the UK 40 years ago this week.

While an all-time classic today, it’s worth remembering that in its day, West End Girls was just an unlikely English rap track from an unlikely new synth duo (just as synth duos were going out of style) and a song that had unequivocally flopped all across the globe a year earlier.

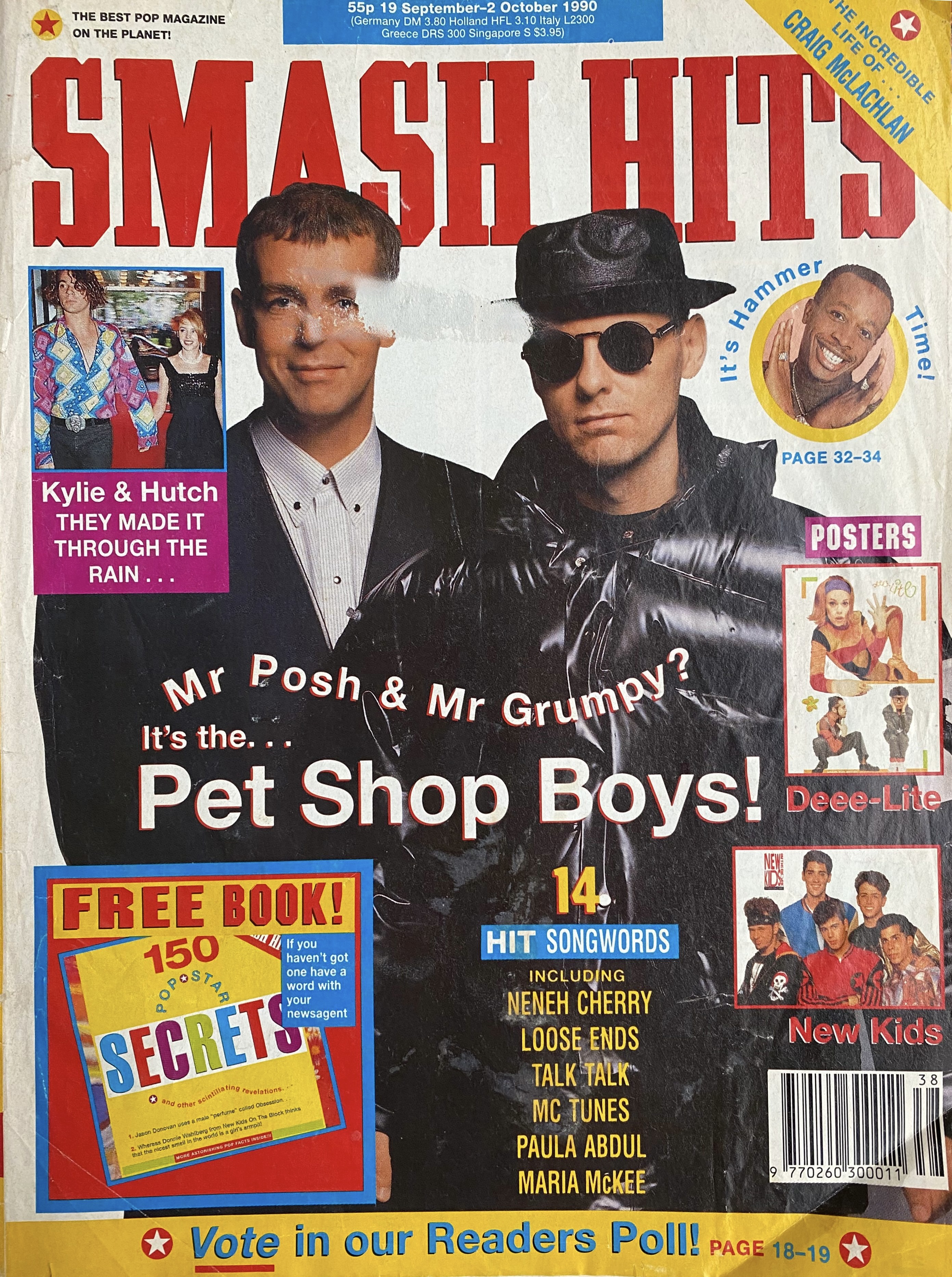

The original version of West End Girls was produced by U.S. Hi-NRG producer Bobby Orlando for his own Bobcat Records and released through ZYX in Europe. The story goes that vocalist Neil Tennant, then the Associate Editor of UK pop magazine Smash Hits, was on assignment to New York to interview The Police in advance of their Shea Stadium gig in August of 1983. However, spotting a gap in his schedule, he sneakily stole some downtime in order to visit someone he’d much rather be speaking to.

Using the magazine’s sway, Tennant had secured an audience with Orlando (aka Bobby O) and, after hitting it off, Tennant played a demo of his unnamed band’s hit-in-waiting, Opportunities, recorded at the Camden 8 studio.

It was audibly inspired by Orlando’s work of the time, and a flattered Bobby O enthused that they should make a record together, and just three short weeks later Tennant, plus keyboard player Chris Lowe, were in Unique Studios off Times Square, New York with a publishing deal and an in-progress instrumental attracting Orlando’s attention.

Here today, built to last

“I had written a rap and I thought I could do it over this music. It was the first time I ever sang West End Girls,” Tennant explains in the band’s 2006 Life In Pop documentary. “Chris hadn’t even heard it over the music.”

“I was staying at my cousin Richard’s house outside Nottingham and he and I had stayed up watching some kind of James Cagney gangster film on the television,” describes Tennant regarding his rap’s origin.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I was sleeping in this tiny single bed and for some reason the line ‘sometimes you’re better off dead, there’s a gun in your hand and it’s pointing at your head’ came into my head. So I got out of bed and wrote it down on a piece of paper.

“Then when I got back to my flat in the King’s Road I lay on my floor one night and wrote the whole thing,” he writes in the booklet for the 2001 re-release of debut album, Please.

Orlando’s take on the song is a far rougher and more raw proposition than the polished global hit of 1985, sharing many of the tropes of his other productions of the time, such as Passion by The Flirts and Divine’s Native Love (Step By Step).

With the tech still inching out of its primordial ooze, multi-instrumentalist Orlando would wrestle with the synchronisation of his early synths, drum machines and Emu Emulator sampler, resorting to playing each robotic part by hand, while trying to sound as mechanical as possible.

And while Orlando’s take certainly still has its earworm charm, with explosive Emulator drums sampling the kick and snare from David Bowie’s Let’s Dance (as many records would go on to do), the song failed to detonate upon its release in April 1984.

While a modest US club hit, its Euro import would only reach number 133 in the UK, while just scraping the French top 30. Meanwhile, its follow-up, the Orlando-produced One More Chance, failed to capitalise, failing to chart precisely anywhere.

Sometimes you're better off dead

With Orlando busy dodging litigation from other acts, it seemed that his ‘p-a-s-s-i-o-n’ for the Pet Shop Boys was soon on the wane, and feeling trapped in a contract with a producer who never seemed to finish anything, the band made the bold move to pay off Orlando with a cut of future royalties in return for ‘one more chance’ elsewhere.

However, with Orlando’s productions as their calling card, the band were able to attract the attention of manager Tom Watkins. Watkins – the man best known for birthing Bros and East 17 – brokered a deal with EMI’s Parlophone and put them in the studio with J.J. Jeczalik and Nicholas Froome (two of Trevor Horn’s backroom boys at Sarm Studios) to make a go of Opportunities (Let’s Make Lots of Money).

Unfortunately, their first major label release only fared a little better than their Bobby O output, reaching 116 in the UK.

What to do next?

“We wanted to release West End Girls again after we signed to Parlophone but we had to rerecord it because we didn’t own the recording,” explains Tennant and, after admiring Stephen Hague's work on the World Famous Supreme Team’s Hey DJ and Malcolm McLaren’s Madame Butterfly, had a new producer in his sights.

"We met a couple of times but I wasn't too thrilled with their material at the time,” recalled Hague to Music Technology magazine in 1988. “I did like West End Girls though, because it seemed as though Neil was born to sing it – everything was working for his voice. I also like them personally too so when EMI secured the recording rights, we began work on West End Girls and, with the band's blessing, I started to change the track.”

Hague went to town, being inspired by the original but choosing to play and program every instrument himself and even change its tempo, music and lyrics. “I wanted to slow it down, change the bar structure, and tidy up some of the lyrics,” Hague explained.

“We brought back the Major seventh chord as well, which hadn't been on the landscape for a while… I wrote the chords at the beginning and the end… I guess I should have pushed for a cut of the publishing, but I was a little green at the time,” he admitted to the 80sography podcast.

Recording took place at London’s Advision Studio in June 1985, and, thanks to the only live instrument being a single cymbal strike at 2:11 – their Studio 2 – a small but well-equipped, remix/overdub suite – fitted the bill perfectly. With house engineer David Jacobs at the controls, he and Hague set to work.

Which do you choose? A hard or soft option?

Using an Oberheim DMX the pair programmed the drums for the entirety of the track, syncing it to its own bespoke time code recorded on track 23 (with track 24 on the studio’s Otari MTR90 being reserved for driving the automation of the SSL desk).

“There was very little pre-production necessary because the previous recording of the track was there as a very thorough demo,” Jacobs explained to International Musician & Recording World in 1986. “We used the time code in case we wanted to change things, but in the event, the only thing we added was a shaker.”

As for the mis-quantised tambourine hit on bar six of both verses (the sixth tambourine hit, instead of appearing on the snare beat, pops up an 8th too early – listen carefully) jury’s out on whether this was deliberate or a glitch in the DMX.

And while there’s no mistaking that West End Girls’ is a hi-tech record with the backroom takeover of drum machines and programmable sequencers in full swing by 1985, liberating music from musicians and placing it into the hands of music lovers with good ideas instead, it’s surprising just how much of West End Girls is actually played live.

With the Oberheim operating very much in its own world, the track’s conga part – consisting of two sounds from an Emu Emulator II sampler – was played entirely by hand. Recorded simultaneously to separate tracks via the keyboard’s separate outs, the lower conga was given a repeat echo on the desk.

Likewise, the riff at the end of the chorus, was composed of a pitched-up choir sample and because “it didn't have enough attack to cut through, we added a cowbell,” Jacobs explains. This tight, rhythmic part was programmed on a Roland MSQ-700 sequencer. However, with the MSQ unable to sync with the DMX’s code, Hague and Jacobs fired in the sequence ‘live’ each time they needed it, hitting Play on the MSQ at just the right moment.

That same Emulator choir is used in the solo too. Ah yes, West End Girls’ trumpet solo – another airing of the over-worked Emulator II with the trumpet sound from its factory library. Again, it’s played live, and, with the band not in attendance, performed by Steven Hague himself.

Inspired by a snatch of melody from the sample cacophony in the bridge of the original version, Hague borrowed five notes from Orlando’s solo (“I said to Neil, well, you own the master…”) and took that as inspiration for a whole new trumpet line.

“I did it as one take. It was just me dicking around. I’m not much of a player player at all,” Hague admits. Jacobs, however, has another recollection. “It took about six hours to get the trumpet part to sound genuine, purposely playing wrong notes to make it sound more 'jazz',” he recalls. Lowe agrees, stating in the album’s re-release booklet, “He spent ages doing it.”

Another new addition to the track was backing vocals. With Tennant simply doubling his vocals an octave down during the choruses, there were no harmony parts to speak of. Thus, backing singer Helena Springs was given free reign to contribute whatever the seasoned session pro could come up with.

“Helena just sang ideas all through the track, the best of which we then sampled into the Emulator so that we could spin them in wherever we wanted,” explained Jacobs. In the end, just two of her lines made the cut, with “How much do you need?” appearing twice and “How far have you been?” three times.

Meanwhile Tennant’s own vocals were recorded with two mics, a Neumann KM84i for the verses – “to get the full bottom end” – while the choruses were recorded with a Neumann U87, “which I never use for vocals because you can't get any top out of them, but Neil's voice is very sibilant, so it worked well in this case,” explained Jacobs.

There’s a madman around

All of which just leaves West End Girls’ distinctive, thudding bass part. Again, it’s all played live, and pop TV viewers of the time will recall being introduced to Lowe, the band’s silent partner, as he battered the hell out of the bottom octave of a scissor-standed PPG Wave 2.2.

In an age where mimed TV appearances were the norm, keyboard players would more usually grasp ownership of any lead line or dramatic musical ‘event’ in a track regardless of where it came from. Guitar and sax solos would suddenly become keyboard fare… Multiple fingers would be outstretched… Arms would vigorously jab and pierce the air… And faces would be pulled as if it were their eyebrows that were making the sound.

So when Lowe opted for the repetitive chore of solemnly finger-banging West End Girls’ bassline while his right arm took the night off, audiences were – at the very least – intrigued. Indeed, UK DJ Steve Wright introduces the Pet Shop Boys debut Top of The Pop performance (video above) as, “A most unusual song from an unusual band”…

“When West End Girls started to take off, it was then that we started to think about the presentation of ourselves,” Tennant mulls in their 2006 documentary A Life in Pop. “What were we going to look like? What were we going to do? We didn’t have ‘an act’.”

But a performer chin down, dodging eye contact and radiating that he really didn’t want to be there WAS an act, and would stick in both the public’s throat and consciousness simultaneously. The band’s routine ‘non-performance’ of the song would become the talk of the playground and workplace after every ‘do we really have to?’ TV appearance.

Thus Lowe’s diligent bass duties during West End Girls’ promotion played a huge part in successfully minting the band’s much-loved, stand-offish, anti-pop ‘Mr Posh and Mr Grumpy’ Smash Hits persona that still endures to this day. “Reluctance was very much built into the concept,” Tennant admits.

And Lowe has continued in jobsworth ‘I just do basslines’ mode for practically every TV performance ever since.

And that bass sound? Not generated by the PPG Wave 2.2 and Waveterm sampling module that were routinely wheeled out for Lowe to hide behind, but the combined output of three completely different synths: A Yamaha DX7 – the de rigueur digital FM synth of the moment – a Roland Jupiter 6 – the poor relation younger brother to their flagship analogue Jupiter 8 and Roland’s first keyboard with MIDI – and an Emu Emulator II – the ‘affordable’ sampling keyboard (which still cost $8000 or about $25,000 in today’s money) which would go on to earn legendary status in Ferris Bueller’s bedroom and countless subsequent Pet Shop Boys TV outings.

“The DX-7 voice was a very low pitched, percussive sound; it didn't have much of a note but it gave the thing depth and attack,” explains Jacobs. “The Jupiter provided the body of the sound, and the Emu II was actually playing a bass drum sample, the pitch of which changed as it was played on the keyboard to add some punch.” All three keyboards were then simply daisy-chained with MIDI leads – Out to In, Thru to In – and played and recorded live.

A final dash of stereo spread via the studio staple of the time, the AMS DMX 15-80S stereo harmonizer, completes the sound, “with a setting of 0.999 on one side, 0.998 on the other and the uneffected signal in the middle,” revealed Jacobs. “When mixing to digital, it gives a kind of ADT or wavering effect that the rock-solidness of digital can lack.”

The Emulator II (this time teamed with the older Emulator I) would also provide perhaps the song’s most memorable and moody elements – its slow, legato strings. Both Emulators play the same part with the I using its Strings preset (a sound and part directly borrowed from the Orlando version) and the II serving up its more complex (and famous) Marcato Strings alternative. “There's also a third low string part that we did on the Emulator II to give it some depth,” says Jacobs.

It’s worth noting that Marcato Strings also appears all over the band’s debut album, Please, each time replacing what could/would/should have been synth chords with the ‘real’ sound of an orchestra instead. Thus, the preset would become a major part of defining the PSB’s sound and effectively gave ‘just another synth duo’ their own unique, enduring signature.

A dive bar, in a West End town

But let’s rewind to the start. Just what are we hearing in the track’s famous, instantly recognisable intro before its first explosive snare drum?

Seeking to inject some ‘street’ vibes into the track, and armed with the new Sony Professional Walkman WM-D6C – a larger, ‘pro’ version of their world-conquering portable cassette players that, this time, featured the record heads that its forebears had stripped away – producer Hague walked the mean streets around London’s Advision studio harvesting whatever the night would throw at him.

And while the D6C was still only a mere cassette recorder, its fresh-for-’84 Dolby C noise reduction does a mean job of keeping the sound sufficiently high-end even by today’s standards.

So what can we hear? Well, there’s West End Girls’ unmistakable ‘city ambience’… And that car horn… Those high heels on pavement… But there are other more remarkable and long-debated insertions too.

Ever wondered just what the girl in the intro is singing?

In every city, in every nation

Advision Studios were at 23 Gosfield Street, Fitzrovia, London, and, being in the heart of the trendy capital, had some similarly high-profile neighbours. Such as Simon Napier-Bell, the then manager of pop flavour of the day, Wham, whose Nomis Management (Nomis is Simon backwards) had their office directly opposite at number 17.

Once word had got out that George Michael and/or Andrew Ridgely would very occasionally stop by for a debrief, the narrow street between Wham HQ and Advision had acquired a 24/7 detail of weary Wham fans, ever hopeful for an encounter with their heroes.

Thus, anyone entering or leaving the studio would have to run Wham’s gauntlet, and so it was, on the fateful night that Hague took to the streets to capture London’s contribution to West End Girls.

Hague recalls approaching that night’s Wham deployment, whereupon one spotted that he was holding a tape machine and a microphone and, buoyed by the group's shared hysteria, actively worked to ensure that they were immortalised. “Get on the my-eye-cro-pho-ooown for-eeever…” they sing sarcastically as Hague passes, simultaneously becoming a part of his nocturnal recording, and a key, unwitting, uncredited performer on one of the most enduring pop records of the past century.

And thanks to detective work by mu:zines’ Ben and Kirk D. Keyes of synthroom.com (who was privy to Hague’s tapes as part of prep for planned but aborted first Pet Shop Boys live show) we can enjoy this performance, here, isolated, 40 years later.

That their impromptu vocal is perfectly in tune with the inaudible-to-them and yet-to-be-finished track is unfathomable, but the moment – forever frozen in pop – is clearly audible at 14 seconds in and, if you listen very carefully, even gets an encore at 4:04.

Tennant also describes in the Please re-release booklet how Hague also recorded one of Wham’s acolytes blurting “It’s Sting!” as he approached. “If you listen carefully, you can hear a girl at 0:05,” he says, Hague’s mistaken identity due to the fact that, like much of fashionable London in 1985, he was sporting the same spiky bleached blonde ‘do’ as the Police frontman. “Stephen Hague looks a bit like Sting,” Lowe confirms.

However, while Keyes HAS been able to ascertain that this is indeed true, and such a recording exists – the girl says “It’s Sting!” and then, disappointed, “That’s not Sting…” – this part of the tape was not used on the finished West End Girls as Tennant assumed. Actually.

Upon returning to the studio, Hague had been particularly pleased with the passing cars and the click of the heels on the street, and hastily plugged his Walkman into the desk. “I wound the tape back to the start and said, ‘Let’s just see if we’ve got anything’. I hit play and David hit play on the multitrack… And it was exactly like it sounds on the record… There were no edits, no anything… And the girl singing the little song… And the car driving away… I said ‘Shit, we should have recorded that!’ and David said ‘I did record it…’ And that was the record. I took that as some kind of sign.”

Faces on posters, too many choices

Likewise, some kind of trickery was afoot in the song’s video directed by Andy Morahan and PSB photographer and style guardian Eric Watson. The video features – in order of appearance – a deserted Wentworth Street (part of Petticoat Lane Market), bustling Waterloo Station, the South Bank, Leicester Square, and anti-apartheid protesters outside the South African embassy on Trafalgar Square.

It also memorably stars a ghostly, transparent Chris Lowe, faded in from a second take of each shot, and the duo fleetingly become a trio when, unbeknownst to the band, Tennant and Lowe are joined by a passing rough sleeper, who magically walks in sync with the track during their 0:34 reveal.

And second time around, West End Girls certainly had some kind of mojo. Following its October 28th release in 1985, the single charted in the UK on November 16th at number 80. From there it rose, week by week, 59… 40… With its number 23 position earning them the Top of the Pops debut, above. From there, a final ascent to the summit of Mount Pop ensued.

9… 5… 4… 3… Narrowly missing the coveted Christmas number one slot, before – with his Christmas bubble having burst – dethroning Shakin’ Stevens’ Merry Christmas Everyone on January 5th 1986 – 40 years ago this week.

The song would also top the charts ‘from Lake Geneva to the Finland Station’ (or more accurately Finland, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, Norway and the States) shifting 1.5 million copies in total, and staying on the US Billboard Chart for 20 weeks.

Its success would help shift over one million copies of debut album Please in the States alone, was crowned The Greatest UK Number 1 Ever in by The Guardian in 2020 and would spearhead an onslaught of hit Pet Shop Boys singles across the decades to follow.

And, of course, it’s spawned an inevitable raft of genre-spanning recreations from – among many others – East 17, Sleaford Mods, Prayers (featuring Travis Barker), The HotRats and even West End Girls by… err… West End Girls… And special props to The Flight of the Conchords’ Inner City Pressure of course.

Meanwhile Pet Shop Boys themselves continue to record and tour to this day. New album Disco 5 out now and – in addition to their ongoing Dreamworld stadium gigs – a series of five intimate live shows at London’s Electric Ballroom are planned for April 2026, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of their debut album, Please.

“People endlessly ask us what it’s like having a number one,” Tennant told Smash Hits back in 1986. “But what it feels like is vaguely nothing. It feels like having a cup of tea”.

Perhaps following 40 years of plaudits, he may be a little more effusive about his band’s biggest hit.

But we wouldn’t bank on it.

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Pet Shop Boys - West End Girls (Official Video) [HD REMASTERED] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/p3j2NYZ8FKs/maxresdefault.jpg)