“The first three times I performed it in public, I burst into tears – because it brought back the intensity of the experience”: How Joni Mitchell wrote Woodstock – an era-defining song that spoke to a generation

An anthem inspired by the legendary music festival – by an artist who wasn’t actually there

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s been hailed as a defining anthem for the late-’60s counterculture, a song that celebrates peace, hope, utopian ideals and a desire to “get ourselves back to the garden”. All set against the backdrop of anti-Vietnam War protests, political turmoil, race riots and deep social disaffection.

The song is Woodstock, written by Joni Mitchell.

By the beginning of 1969, the mercurially gifted 25-yr-old Canadian was arguably best known for the songs she wrote for other artists, such as Both Sides Now, which became a No.8 hit in the US for folk singer-songwriter Judy Collins in October 1968.

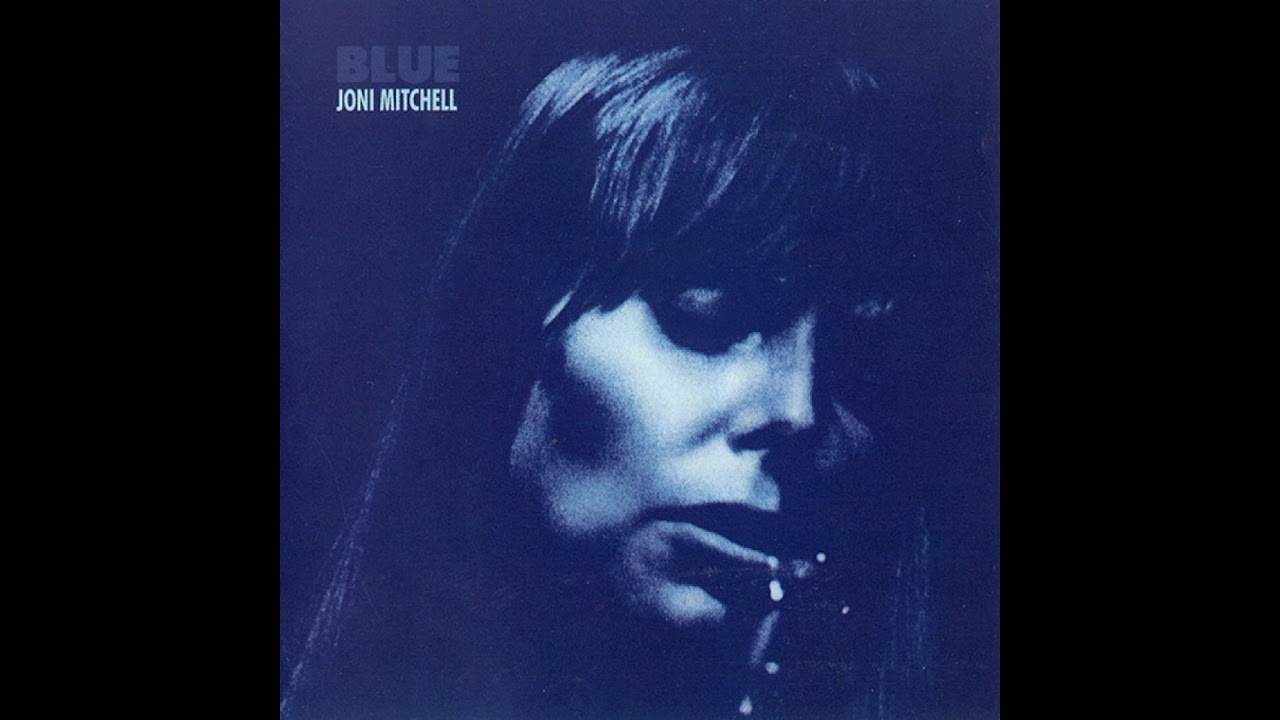

But by the time Mitchell wrote Woodstock in late August 1969, she was in the ascendant as an artist in her own right, going on to release the albums Ladies Of The Canyon (1970) and Blue (1971), which yielded huge critical and commercial success.

Peers such as David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young (CSNY) were in awe of Mitchell’s artistry, acknowledging her as someone with a talent that was equal, or even superior to, their own.

Over five-and-a-half decades on, the song Woodstock still resonates with its message of hope, peace and unity in a turbulent, trouble-strewn world.

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair, as it was initially known, was conceived in early 1969 as a profit-making venture, with an estimated attendance of 50,000 people. But poor planning resulted in fences and ticket booths not being constructed in time. The result was logistical chaos.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Within hours of the first day, Friday 15 August 1969, the bewildered organisers had declared Woodstock a free concert after the crowds overwhelmed the incomplete fences and ticket booths. By then, it was also dawning on the organisers that they had woefully misjudged audience numbers.

By Saturday 16 August, between 400,000 to 500,000 people were estimated to have descended on the festival site at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in Bethel, upstate New York.

All roads in and out of the area were soon completely log-jammed, with people simply deserting their vehicles and walking the rest of the way.

Joni Mitchell was booked to play on Sunday 17 August – and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young were also scheduled to perform. They were all then due to appear as guests on the The Dick Cavett Show, which was being recorded in uptown Manhattan on Tuesday 19 August 1969.

But by the time Mitchell, Crosby, Stills and Nash arrived at JFK airport, everyone knew about the logistical challenges at Woodstock. Mitchell’s agent, David Geffen, was concerned that she may not make it out of the festival site in time to appear on the Dick Cavett Show.

“It was a catastrophe,” Mitchell told Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) show The National, “and it was Geffen that decided, ‘Oh, we can’t get Joni in, and we can’t get her out in time’. He took me back to where he lived. We watched it on TV.”

And so it was that Joni Mitchell, the writer of the song inspired by the most iconic music festival of all time, wasn’t actually at the event.

Instead, she stayed in Geffen’s New York hotel suite, watching TV news reports from Woodstock.

By contrast, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young did appear at the festival, on the final day. They didn’t go on until 3am on the Monday, but it was a landmark performance. And as Stills famously told the crowd, it was only their second gig.

“This is only the second time we've played in front of people, man,” Stills told the crowd, “We're scared shitless!”

Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash were romantically involved at the time, and it would be Nash’s observations of the festival that would help inform Mitchell’s lyrics for the song.

She began composing the song in Geffen’s hotel suite. The decision not to perform at Woodstock would haunt Mitchell, but she also recognised that it gave her a unique perspective as a songwriter.

“The deprivation of not being able to go provided me with an intense angle on Woodstock,” she told William Ruhlman in a 1995 interview for the magazine Goldmine. “I was put in the position of being a kid who couldn't make it. So I was glued to the media.”

Mitchell confided that she was going through “a kind of born again Christian trip” at the time, which influenced the writing of Woodstock.

The spectacle of almost half a million people peacefully huddled together in the rain and mud to listen to rock music had a profound impact on her.

“I was a little ‘God-mad’ at the time, for lack of a better term,” she told Ruhlman, “and I had been saying to myself, 'Where are the modern miracles? Where are the modern miracles?'. Woodstock, for some reason, impressed me as being a modern miracle, like a modern-day fishes-and-loaves story.

“For a herd of people that large to cooperate so well, it was pretty remarkable and there was tremendous optimism. So I wrote the song Woodstock out of these feelings…”

Religious imagery pervades the song’s lyrics, which recount the tale of a spiritual journey to the festival site at Yasgur’s farm. The song likens the Woodstock Festival to the Garden of Eden and evokes a sense of pilgrimage alongside fellow travellers: “Well I came upon the child of God/He was walking along the road…”

The spiritual journey continues into the third verse: “By the time we got to Woodstock, we were half a million strong,” begins Mitchell, before introducing a contemporary thread at the verse’s end. “And I dreamed I saw the bomber jet planes/Riding shotgun in the sky/Turning into butterflies/Above our nation.”

It’s beautifully realised, evoking the utopian moment while referencing the grim futility of war.

Mitchell wrote and recorded the song on a Wurlitzer electric piano and the instrument’s lush textural tones enhance her slow, haunting arrangement.

Her vocal is pure and distinct as ever, as she glides seamlessly through the octaves with real emotional power and conviction.

Her thickly-layered backing vocals first appear at 1:45 and bring a rhythmic element to the song.

Four versions of the song Woodstock would eventually be released by four separate artists, all in 1970.

The song appeared on Mitchell’s 1970 album Ladies Of The Canyon and as the B-side of her hit Big Yellow Taxi.

British band Matthews Southern Comfort’s cover became the best-known version in the UK, where it topped the UK Singles Chart.

Then there is the instrumental version, recorded by an ensemble of crack Philadelphia session musicians called Assembled Multitude. Their version of Woodstock peaked at No.79 in the US Billboard Hot 100 and reached No.23 in the Billboard Easy Listening chart.

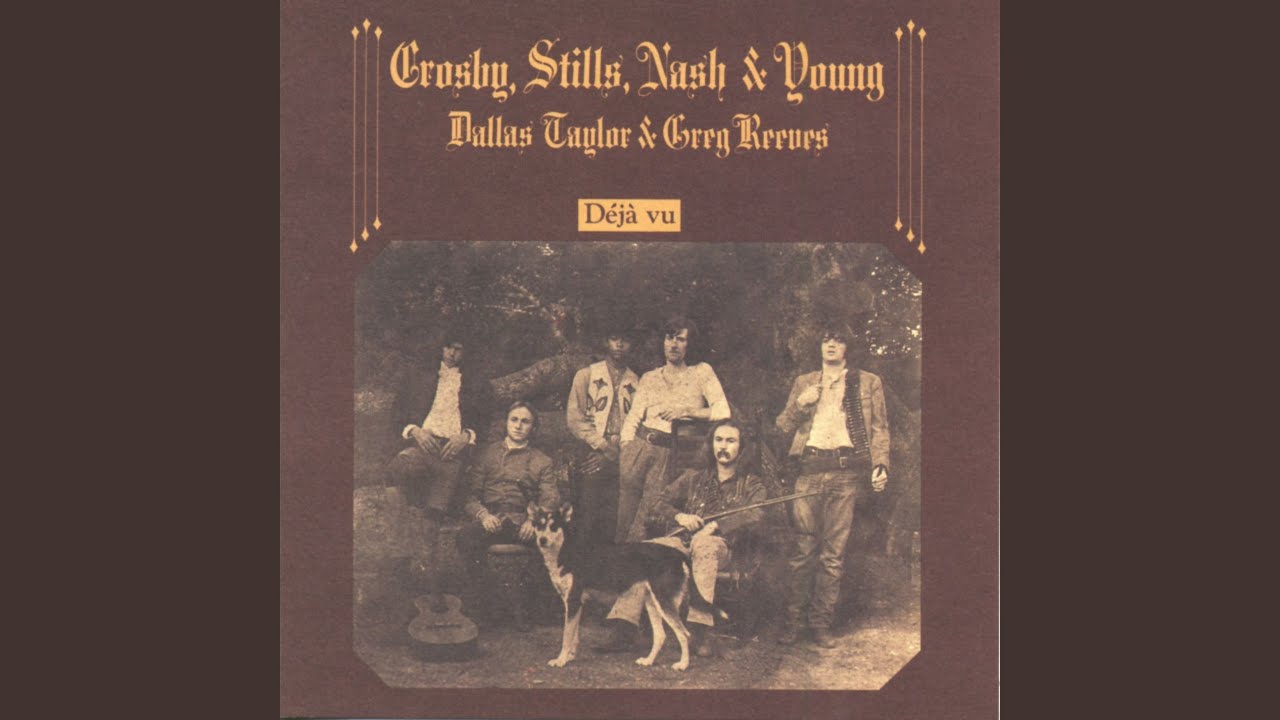

But by far the most well-known rendition of Woodstock was the one recorded by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and released as the last track on side one of their colossally successful album Déjà Vu.

Released on 11 March 1970, Déjà Vu topped the Billboard 200 chart and yielded three singles, one of which was Woodstock.

The CSNY version is a completely different beast however – jagged, edgy and assertive, and elevated by Stills’ wonderfully gritty and soulful vocal performance.

David Crosby was in awe of Mitchell’s song and credited Stephen Stills for turning her composition into a powerful rock anthem

24 hours after CSNY took the stage at Woodstock, David Crosby and Stephen Stills were on the sound stage of the Dick Cavett Show in Studio 2 at ABC Television Centre at 202 West 68th St, in New York. They still had mud from the festival caked on their jeans.

CSNY had made it out of the festival site in time by helicopter, as had the Jefferson Airplane, and all were sat on low stools in a circle around Cavett, who was one of the more erudite and tuned-in chat show hosts of the late ’60s and early ’70s. Cavett’s show that day was completely devoted to the Woodstock Festival.

Joni Mitchell was also on the show and performed four songs – Chelsea Morning, Willy, For Free and the a cappella Fiddle And A Drum. If she felt uneasy as the only artist on the show who hadn’t actually attended the festival it wasn’t that evident.

In the days that followed, she would hone the song Woodstock, drawing on what she had seen and felt while incorporating the reminiscences of her partner, Graham Nash.

One month after the festival she would perform the song prior to its release, seated at a piano, at the 1969 Big Sur Folk Festival.

The song was a powerful evocation of an unprecedented cultural event.

“She contributed more to people’s understanding of that event than anybody else there,” recalled David Crosby in the 2003 documentary Joni Mitchell: Woman Of Heart And Mind.

Despite her not having attended Woodstock, the images of the festival, even when viewed on a TV screen in David Geffen’s New York hotel suite, continued to have had a profound impact on Mitchell.

“The first three times I performed it in public, I burst into tears,” recalled Mitchell in a 1995 interview with William Ruhlman in the magazine Goldmine, “because it brought back the intensity of the experience and was so moving.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.