How innovative minds are developing new technology to support music makers with disabilities

Issues of accessibility present ongoing challenges for disabled music-makers, but a range of different organisations, artists and innovators are aiming to bring about industry-wide change

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“As a blind music producer, before things were more accessible, I would have to rely on my memory and different work-arounds to make music,” says artist, audio engineer and accessibility consultant Jason Dasent on his past creative process.

“If I wanted a certain synth sound, I would have to remember the settings and learn where the dial was by touch and memory,” he says. “Now I work with different manufacturers applying what I’ve previously experienced in recording studios to guide me in how I can enhance their products.”

Jason’s invaluable contribution to the music tech world is aimed at supporting disabled music producers, artists and performers like himself, where the music studio has often been inaccessible, challenging and a sometimes discriminatory space to enter.

Barriers to creativity and music-making are myriad and can stem from a studio’s size to the design of equipment, hardware and software.

Reports have also found that disabled musicians have been discriminated against too. Research from the Musician's Union (MU) and the charity Help Musicians exposed an average pay gap of £4,400 while 88% of musicians who said they are open about being disabled (with some or all of the people they work with) have subsequently experienced discrimination. As John Shortell, the MU's Head of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, says: “Tackling ableism, inaccessibility and discrimination should be a priority for the entire music industry.”

Elizabeth J. Birch is an autistic wheelchair user who works as an industry facilitator, producer and creative and is a key advocate for change amid this music industry landscape. For her, obstacles to access can be physical, emotional as well as financial in the midst of an ongoing cost of living crisis.

“One downside to certain bespoke music tech pieces is the cost - can people afford the accessible tech that is being created?” she says. “Unfortunately, you can’t just pick it up off the shelf at the moment, much of this is bespoke, which means it can be very expensive.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“My goal is to tackle these issues by working with industry organisations that want to make the music industry as accessible as possible to as many people as possible - that instills a sense of diversity and is how we get to new creativity and ideas in music.”

Jason Dasent is a producer, artist and accessibility champion who spends much of his time collaborating with industry stakeholders and gear manufacturers looking to evolve their products.

As a blind creative, originally hailing from Trinidad, now based in Sheffield, Jason currently works with 12 different companies. His mission began while running a studio in Trinidad with his wife Sarah and investing in a Native Instruments Maschine that proved to be totally unusable.

“It might as well have been a doorstop for all I could do with it when it arrived as it didn’t support text to speech,” Jason says. “But I have always been techy so using a program called Keyboard Maestro, myself and Sarah built macros to include a keyboard shortcut where the mouse moves to the Play button, then clicks. It worked and we started adding more macros to access different functions.”

By the time Jason and Sarah had finished, there were 600 macros running every aspect of the device. Native Instruments found out about their work and invited them to a meeting. Jason was subsequently hired to help support the embedding of accessibility into equipment from the early design stages.

Since then, he has worked with an array of developers and companies including what he sees as one of his proudest achievements so far, the Softube Console 1. This MIDI controller includes a screen reader, settings for automatic meter readings and touch sensitive knobs.

“The accessibility side is so well developed for the Console 1, it’s almost like I’m not blind when I use it,” says Jason. “Some of the features have been issues plaguing visually impaired people for years and hopefully we have solved many of their insecurities.”

While he sees increasing awareness within the music tech sector of the need to make products accessible, Jason is also looking to impress on businesses that embracing this is a win for the entire industry ecosystem.

“I always worry when I hear people say they want to do this as it’s the right thing to do,” he explains. “Of course it is but you need to realise it can benefit everyone - it’s not a charity situation. There are thousands of visually impaired musicians and producers out there, meaning they win as they are able to do more, it boosts their ability to find employment, and the company wins as they can now sell to a bigger market.”

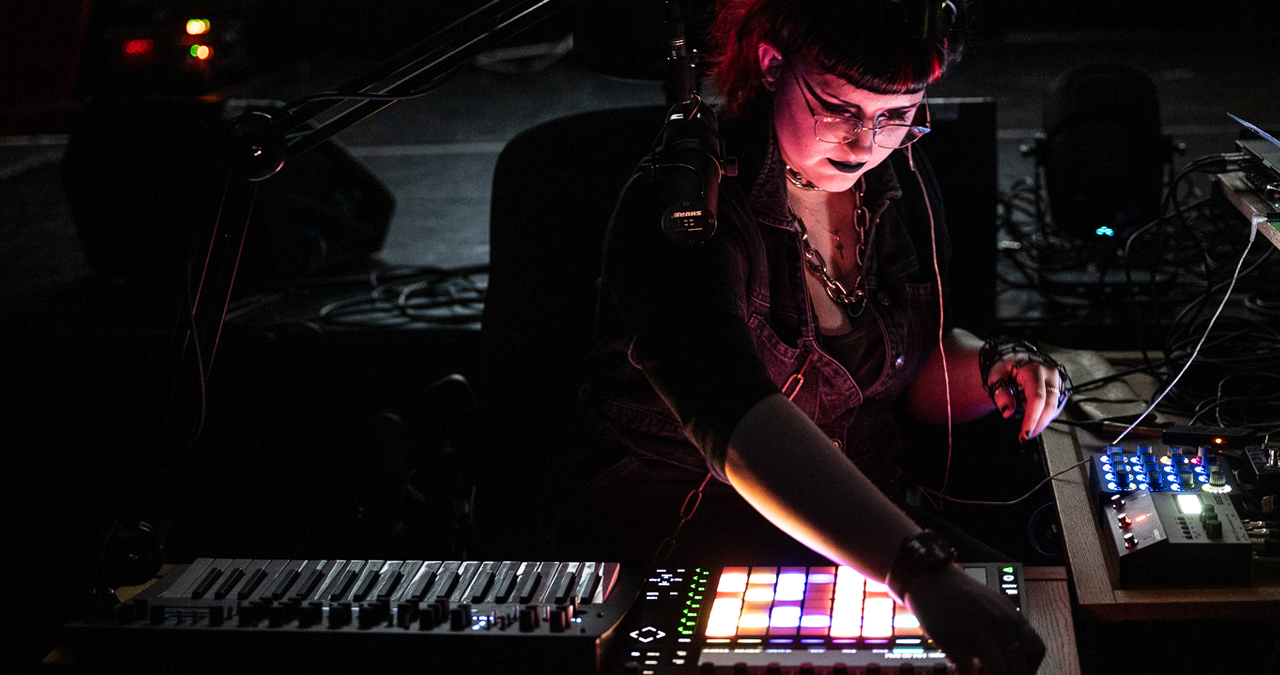

Elizabeth J. Birch is not only a producer and artist but also a vocal campaigner for industry change. She was named winner of the Inspirational Music Leader Award at the Youth Music Awards 2023, then featured as a Mastercard Trailblazer ahead of the 2024 BRIT Awards. Her music is glitchy electronic pop made in a home studio where technology includes a Mac, two primary DAWs and a Korg Minilogue. As a wheelchair user, her set up has been designed to empower her experiments.

“Technology has allowed me to be more fluid in how I approach my music,” she says. “If I tried to play piano live for a full 30-minute set, I’d likely dislocate my fingers and be exhausted afterwards. So I utilise loops when doing live gigs for both easier access and to develop my own style.”

Elizabeth is also a fan of the Korg due to the labelling and location of certain features. The lesser the learning curve for a piece of kit, the easier it is to avoid being overwhelmed and put off making music.

“I’m autistic so I can sometimes struggle to decipher how something works,” she says. “The Minilogue is not perfect as there is some menu-diving, which doesn’t suit those with visual impairments. But it’s easy to find the oscillator and filter, it’s in an order and is clearly labelled. I use a lot of tech for teaching and recording sessions and to know where something is and what it does is vital.”

She’s also a fan of the Ableton Push, in part due to its tactile pads and the lights featured on its user interface.

“Due to my autism, I’m very sensory but I can also be sensory averse as well as being a fan of certain things,” she says. “Considering tech from this perspective has been really fascinating and figuring out what my eyes like to see and fingers like to play, all those kinds of things will hopefully facilitate the best music I can make.”

Of course, the music tech sector moves at a rapid rate - and with new products, platforms and software come new challenges for music producers with access issues. During the last year, Elizabeth has also had to reevaluate where she invests her energies due to health reasons.

“I still host workshops and teach but I’m also trying to focus on making music and being creative,” she says. “I wanted to do more music but it wasn’t paying the bills, then when I would come back to it, I wouldn’t have any energy to invest in it. That’s been a really interesting question from an access point of view - how do I distribute my energy levels across these various contexts to sustain a career?”

Alongside tech companies like Reaper, Native Instruments, and Arturia that are looking to develop accessible products, other organisations such as Attitude is Everything, Help Musicians’ UK and the Drake Music are working to improve the industry too. The latter is a national arts charity operating where ‘music, disability and technology meet’ and does so by facilitating opportunities, workshops, events alongside creating instruments.

“During the last few years, there has been a massive effort from lots of different companies to enhance accessibility,” says Drake Music’s Tim Yates, a Research and Innovation Executive who, alongside his role with Drake Music, designs instruments and sound installations.

“Many of the big changes have been in screen reading tech, which is now built into plenty of production software,” he continues. “From JUCE through to Ableton and Pro Tools, all of the major DAWs have undertaken work to improve this which makes a massive difference. Many accessible features usually become general interface features too. Everyone wants to avoid menu-diving and navigate their sample library more efficiently, so it’s quite common for this to happen.”

Drake has created a community of designers, instrument-builders and product developers to share ideas with many different innovations coming to life.

Some of the most notable include the Kellycaster, a guitar which was designed to cater for the specific needs of disabled musician John Kelly and the Mi.Mu Gloves, a musical interface developed by a team led by singer-songwriter Imogen Heap. Having identified their potential to enhance accessibility, the Drake Music team worked with Mi.Mu to uncover how they might be used by disabled musicians and performers.

“Our goal is that everyone everywhere has an instrument they can play at an appropriate level for them so they can make the music they want to make,” says Tim. “For that to happen, we want to develop an idea, then work with the various different stakeholders to aim for change across entire workflows.”

Hunaid Nagaria is a creative technologist and part of the Drake Music’s Accessible Instrument Development Fund programme. This initiative aims to support innovative ideas that could make a difference to the lives of music makers.

Previously, Hunaid unveiled Jammies, a set of musical instruments designed to improve the quality of life for people living with mild to moderate dementia by empowering them to reminisce, improvise and jam along to their favourite music. His latest idea is Midas, a wearable glove-like interface with fabric force sensors on the fingertips.

“After Jammies, I was looking for a thesis project and became interested in gaming, where about 20% of players identify as disabled,” Hunaid says. “I focused on Muscular Dystrophy (MD), where muscle weakness can make traditional controllers especially difficult.”

With the interface, users press against any surface - a spoon, a phone case, a table - and the pressure is measured as input. After the initial idea was given life, Hunaid soon pivoted from applying them in gaming to music making.

“Ruud van der Waal from music tech organisation My Breath My Music pointed out that the same gestures used in games - pressing, holding, tapping - are foundational to making music,” he says.

“Suddenly, Midas wasn’t just a controller, it was an instrument. Today, I’m developing it further with support from the Accessible Instrument Development Fund, refining the sensors, building more robust printed circuit boards, and collaborating with musicians to explore its creative potential.”

Among the many numerous tech companies to have developed ideas is Soundbeam. Rather than typical music production software that uses a keyboard and controller interface, this touch-free device utilises physical movement and wireless switches to help generate sounds.

Co-director Adrian Price traces its roots back to the Thereminvox, a Russian invention of 1920 which inspired Soundbeam’s originator Edward Williams to search for a device that could help dancers create and shape music through their own body movements.

“The prototype of Soundbeam was built in 1984, and by 1989 the machine was being produced commercially by Cornwall-based Electronic Music Studios (EMS), developers of the VCS3 - the first synthesiser to be widely used in schools and universities, and by the more adventurous rock groups,” Adrian explains.

“Soundbeam uses ultrasonic polaroid transducers to detect distance and movement, the range can easily be adjusted to recognise movement within a very small area, as little as one centimetre for those with very limited movement, perhaps just facial movement - and up to five metres for those who might like to dance or move in their chair like Ari Kinarthy.”

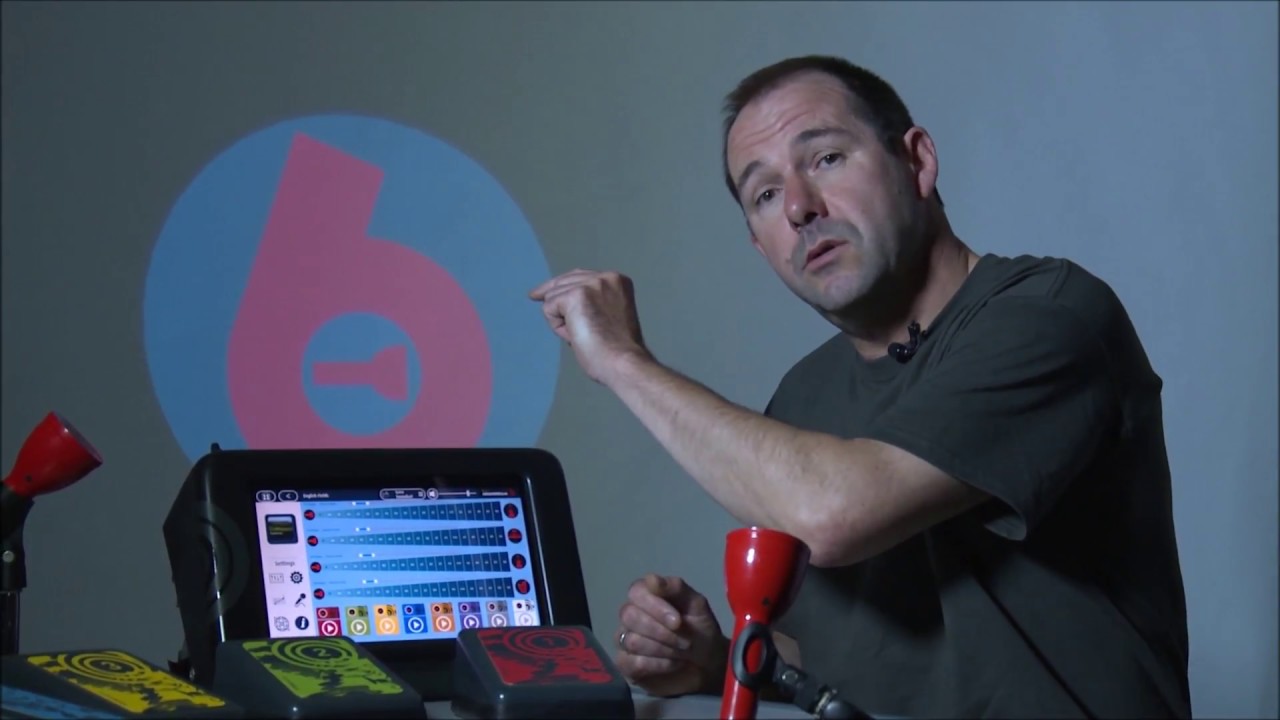

Initially, the system used just one beam to detect movement but since its first release, through collaborations with musicians and teachers, four beams and eight switches can now be utilised, making it suitable for group performances. The latest Soundbeam 6 also has a library of samples it can be used with, removing the need to connect it to third-party hardware or software.

“We have tried to develop a stand-alone system that is as easy to play, operate and program as we can make it, and it’s designed with the needs and abilities of the technophobic player and facilitator in mind,” says Adrian. “You don’t need to be a musician or music technician to be creatively successful with Soundbeam.”

Indeed, there are various artists, bands and collectives around the world utilising Soundbeam to make their music, including 5a Punkada, Orchestra Scia Scia, the good peoples orchestra and Tabulamusica.

“I’d like to think that with the use of technology and a creative mindset, that anyone can make and create great music these days,” Adrians says. “As with any creative musicianship, it’s about embracing and exploring the skills you have, using the instruments and tools that enable and inspire you... and the freedom to play, literally play with sound and music which is where in my opinion the truly great things come from.”

As a PhD student, musician and accessibility lead, Jason Dasent is clearly a very busy man. On Zoom from his home, he demonstrates the power of his fully accessible studio and the pace of his workflow illustrates how far technology has come. There is certainly an air of optimism about the way conversations are progressing among the various players within this part of the music industry.

“As part of my PhD, I’m exploring a Siri-like tool designed for a studio,” he explains. “I’m doing it for visually impaired people but also those with motor disabilities as well - who might be wheelchair bound.”

“I’m also working with educators too alongside manufacturers to enhance accessibility. I just started training staff and students at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. So they will be able to open their doors to visually impaired students who want to study there.”

At Drake Music, Tim Yates is also leading on a key project called the Accessible Musical Instrument Collection (AMIC), a new physical and online space which disabled music makers will be able to visit to test and toy with hardware and software. As well as establishing a collection of existing accessible tech, the AMIC will commission and support the creation of the next generation of accessible instruments.

“At the moment, there’s nowhere in the world for musicians and artists with accessible needs to go and try gear to see if it can help them,” Tim says. “So the idea for this is to build a centre where people can see the features, test them and learn how to use them.”

It suggests, as does Jason’s work, that change is being driven by these vital projects.

“I often question myself initially when I’m suggesting new ideas,” says Jason. “Then you see it come to life and it feels great. A lot of people are depending on you but it’s also totally exciting and there’s nothing else I’d rather do.”

“Even in my own role as a music producer, now being able to come into my studio and do everything from recording to mastering is so huge for me. It’s an amazing feeling.”

Jim Ottewill is an author and freelance music journalist with more than a decade of experience writing for the likes of Mixmag, FACT, Resident Advisor, Hyponik, Music Tech and MusicRadar. Alongside journalism, Jim's dalliances in dance music include partying everywhere from cutlery factories in South Yorkshire to warehouses in Portland Oregon. As a distinctly small-time DJ, he's played records to people in a variety of places stretching from Sheffield to Berlin, broadcast on Soho Radio and promoted early gigs from the likes of the Arctic Monkeys and more.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.