“The band has to get from 10/4 to 4/4 to 7/4 to 4/4 to 10/4. This all happens spontaneously and without prior discussion”: The Grateful Dead's Bob Weir in five songs (and a jam)

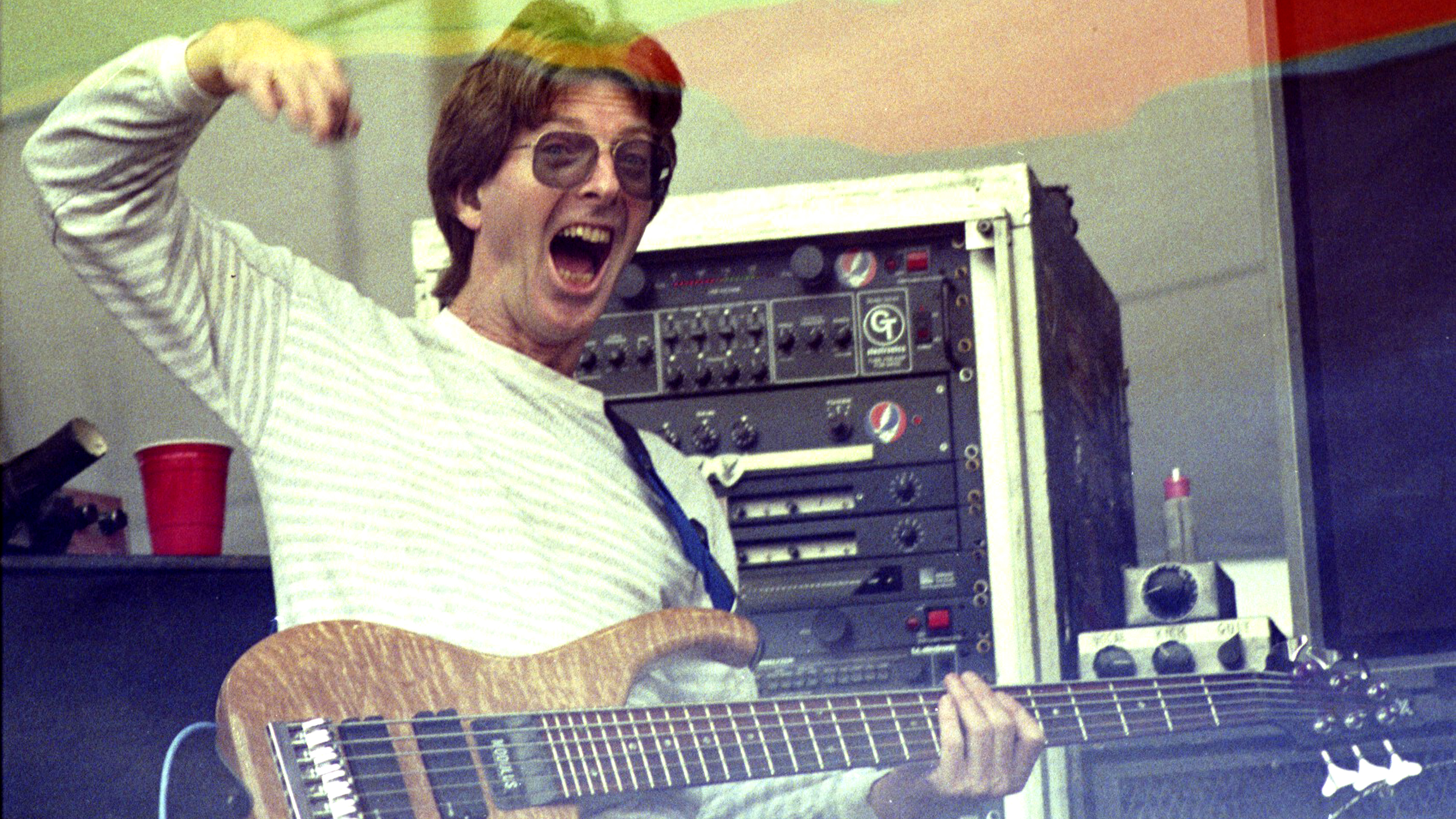

Bob Weir was not an obvious candidate for one of the biggest rock stars in the world, but as the most visible steward of the Dead's legacy, that’s what he became

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Before his death at the age of 78, Bob Weir spent six decades singing and playing rhythm guitar in the Grateful Dead and its various offshoots. Given the awesome span of this career, it’s remarkably difficult to summarize what exactly Bobby did for all of that time.

The 2015 Netflix documentary The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir is named after one of Bobby’s songs, but it was really chosen to reflect his odd position in the Dead. Bobby was a songwriter and guitarist in a band that also included Jerry Garcia, whose songwriting and guitar playing were generationally iconic.

But Bobby had a crucial role too: he was the anchor that kept the music tethered to the earth so it didn’t drift completely away into space. Bobby’s playing functioned the way that the bass would in a normal band. Phil Lesh, the Dead’s bassist, was really a second lead guitarist. While Phil was busy improvising elaborate non-repetitive countermelodies, Bobby’s chords and riffs held the groove together.

As a writer and improviser, Bobby didn’t have Jerry’s effortless melodic flow, but he did have what Phil called an “innate whimsical originality”. Bobby not only wrote a substantial amount of the Dead’s core repertoire, but he also brought a much-needed extroverted energy to the stage in the later years when Jerry and Phil were mostly studying their shoes. He could be a goofball, but he was an engaging goofball.

Here are five high points of Bobby’s songwriting, along with a bonus jam.

1. Born Cross-Eyed

Recorded during the Dead’s most ambitious period of sonic adventurism, this tune was the B-side to the single version of Dark Star.

The song feels like it begins backwards, and from there it only gets weirder. There are Beach Boys harmonies, a trippy/circus-y waltz time section, Phil playing flamenco trumpet, and some pauses filled with what Bobby described as “thick air”. It ends with a hellish explosion of feedback.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The Dead started as a bar band playing electrified folk, blues and R&B, and when they pivoted into proggy psychedelia, their imaginative reach hugely exceeded their technical grasp. This was an especially big challenge for Bobby, who had joined the band as a teenager with novice-level guitar skills.

Jerry, Phil and the drummers practiced obsessively to realize their jazz fusion ambitions, and they felt that Bobby and original frontman Ron “Pigpen” McKernan were holding them back. Pigpen was a blues and R&B guy who wasn’t interested in outer-space exploration at all. Bobby was on board for the adventure, but he didn’t yet have the chops.

In 1968, the band went so far as to fire Bobby and Pig, but they didn’t give up. Bobby hit the woodshed hard, and continued to show up for rehearsals and gigs until everyone just accepted that he wasn’t going anywhere. Within a couple of years, his playing and writing reached full flower, and it became impossible to imagine the Dead without him. Pigpen didn’t recover so well; he withdrew partially from the band and drank himself to death a few years later.

2. Playing in the Band

This setlist staple originated as a groove in 10/4 time that drummer Mickey Hart came up with. During a jam in Mickey’s barn, David Crosby created a guitar riff in D Mixolydian mode to go with it. The band nicknamed this groove the Main Ten. Bobby developed the groove into a full song in 1971. Here’s the version from Skull and Roses, which is a live recording, but with organ by Merl Saunders overdubbed in the studio.

When you catch this song on classic rock radio, its odd meter and structural unpredictability make it feel like an explosion of color in a sea of grey. Interesting though the song is, though, its real significance to the band was as a launchpad for improvisation. After a year of playing it as written, the band inserted a jam section into the second Main Ten break before the second bridge. This jam rapidly expanded in length, and it became a space for wild adventures.

Sometimes these adventures happened entirely within the boundaries of the song itself. The fourteen minute version from 9/21/73 is a good case in point. The 21-minute version from 9/10/72 is even better. The longest self-contained version, from 5/21/74, lasts for forty-six and a half minutes. Maybe you read that sentence with horror, but if open-ended improvisation is your jam, then 5/21/74 will very literally be your jam.

The typical situation was for the band to get to the second Main Ten break and then leave the song behind entirely. Sometimes they would insert another single song into the gap. On 8/6/74, in the midst of an unusually funky PITB, they find their way into Scarlet Begonias. This requires that they get from D Mixolydian in 10/4 time to B major in 4/4 time and back. The transition into Scarlet Begonias is clumsy, but the return to PITB is delicately elegant, and the crowd goes wild when the circle is complete.

Sometimes, the PITB jam leads into a whole sequence of other tunes. There’s an especially cool recursive sandwich from 11/10/73: PITB goes into Uncle John’s Band, which goes into Morning Dew. This then goes back into Uncle John’s Band, which then goes into the PITB reprise. This time, the keys are more closely harmonically related, but the time signatures aren’t; the band has to get from 10/4 to 4/4 to 7/4 to 4/4 to 10/4. This all happens spontaneously and without prior discussion. The crowd goes bananas for the PITB reprise, and rightly so.

On 12/29/77, the band segues from PITB into China Cat Sunflower and I Know You Rider—two songs that also feature an improvisational space between them—and then into China Doll, into a short return to the PITB central motif, into a long drum solo, into Not Fade Away by Buddy Holly, and finally into the PITB reprise to end the set. That’s a seamless fifty-eight minute suite!

3. Jack Straw

Bobby loved cowboy songs, and in addition to singing a lot of them, he also wrote some memorable ones. He co-wrote Jack Straw with Robert Hunter, before they had a falling out over Bobby’s tendency to change Hunter’s precious lyrics. Bobby says that the plot was inspired by Of Mice And Men.

The song’s structure and harmony are deeply peculiar. The verses combine E major and E Mixolydian, a harmonic feel that the Dead used often. There’s an odd-length bar on the line “we done shared all of mine,” and that last word hangs over an extraordinary string of chords: E, G#m, D, A. The move from G#m to D is especially ear-grabbing. It isn’t just that G#m is from E major and D is from E Mixolydian; it’s also a root move by a tritone, a weird bit of neo-Riemannian transformation.

The “I just jumped the watchman” section alternates E7sus4 and E7 while Jerry is singing, then F#7sus4 to F#7 for Bobby’s part. The last F#7sus4 to F#7 pair gets cut off early, forming another bar of 2/4, and moves into a loop of D, Bm, A and E7, putting us back in E Mixolydian.

A normal song would go into the chorus here, but instead, the Mixolydian loop carries us through a six-bar guitar solo and on into the next section, which is like the third subsection of the verse. At the end of the line “not with all…”, there’s yet another key change, to D major. This part alternates D and G before walking chromatically back down to E at the transition back to the intro groove. It’s quite a journey.

Jack Straw has an unusually dynamic tempo, too. On the Europe ‘72 version, the song starts at a relaxed 64 BPM before getting up to 74 BPM at the energetic peak of the first verse, and then in the interlude before the second verse, it drops all the way back down to 65. The Dead could suffer from shaky timekeeping, but in this song, the variable tempo has a nicely expressive effect.

4. Cassidy

After his split with Robert Hunter, Bobby began writing songs with his childhood friend John Perry Barlow, one of the stranger characters in the Dead universe, and that is saying something. Barlow was a part of Andy Warhol’s Factory, a screenwriter, a drug dealer, a staffer on Dick Cheney’s 1978 Congressional campaign, a consultant for the CIA, and, in his later identity as a libertarian activist, the author of A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.

Bobby and Barlow co-wrote wrote Cassidy in 1972 for Bobby's first solo album, Ace, but it found its fullest flower in the late 1980s. The intro and the first half of each verse is in E Mixolydian mode, but then the song switches to parallel E minor, recasting the same harmonic pattern in a darker pitch collection. The last section of the verse is in a vanilla E major, using F#m and A chords.

Like many Bobby songs, this one doesn’t have a chorus, but it does have the “flight of the seabird” section that sits where the chorus would in a conventional song. This part is in B Mixolydian, one slot clockwise in the circle of fifths from E Mixolydian, and the two modes fit together like puzzle pieces. The jam section is an unexpected shift into E Lydian mode, a scale that’s rarely used in rock music. I like the ‘80s version because the keyboard, drum and guitar-controlled synthesizers enhance the mystical vibe.

5. Estimated Prophet

Another collaboration with John Barlow, and another of Bobby’s trademark odd-meter grooves. It’s also the most successful of the Dead’s experiments with reggae.

The main sections of the song are grooves in F# Aeolian/natural minor (the beginning part) and G Mixolydian (the “California” part). These two modes are very distantly related, and the transitions back and forth are intentionally jarring. There’s a bridge (“I’ll call down thunder”) in yet another unrelated mode, E Phrygian dominant, followed by a series of symmetrical chord moves: F, A, Bm, Dm, Am, Cm, Gm, Bbm, Fm, C#, Ddim7, and back to G Mixolydian. Jerry’s Mu-tron envelope-filtered guitar adds to the track’s feeling of sonic enchantment.

Bonus track: The Beautiful Jam

Grateful Dead jams were sometimes built into the structures of their songs, like the “trap door” section in Playing in the Band. However, the most exciting and unpredictable jams happened spontaneously between songs, or just out of the blue.

One of the most beloved jams by Deadheads took place on 2/18/71, which was, coincidentally, the night that Bobby and John Barlow decided to start writing together. The jam comes between Dark Star and the debut performance of Wharf Rat. The Heads nicknamed it the Beautiful Jam, and the band later released it under that title.

As the recording begins, the band is coming out of Dark Star, chugging along in A Mixolydian. Eight seconds in, Jerry plays a prominent D, and Bobby plays a Bm chord to match it. Bobby begins alternating Bm and A every two bars, which forms the backbone of the jam.

While this was a spontaneous choice, it also sounds like the band’s written material. Bobby could throw a Bm chord into an A Mixolydian jam and expect everyone to fall in with it because it’s the kind of thing that they had played together many times before. The best Dead jams sound coherent because they are essentially onstage non-verbal songwriting sessions.

Three minutes in, Jerry plays a loud and accented F-natural, a conspicuously out-of-key note, possibly an unintentional one. Bobby is paying attention, though, and he reacts by putting down a new chord pattern to fit, alternating A and Dm. The Dead didn’t always pay attention to each other so closely, especially in their later years, but when they did, it was exciting to get to hear their musical thinking in real time, and to feel like a participant in it.

It was surprising in the 1980s when Dead suddenly arrived on the pop charts and started selling out stadiums, but it’s even more surprising that their fandom has only grown in the decades since Jerry Garcia’s death.

Bob Weir was not an obvious candidate for one of the biggest rock stars in the world, but as the most visible steward of the Grateful Dead legacy, that’s what he became. He talked about his hope that some version of his repertory band Dead & Company would last for hundreds of years into the future. Considering that the legacy has lasted this long and only keeps growing, he may well get his wish.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.