“No other industry would tolerate this level of loss of life and neither should we”: Science indicates that musicians do actually die younger - but why?

Are musicians and other music industry professionals really at greater risk of an early death than the general public? Studies say it’s true

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s a well-established part of the popular music canon that mythologises the ’27 Club’. That oddly numerically-aligned group of famous artists who all died at age 27.

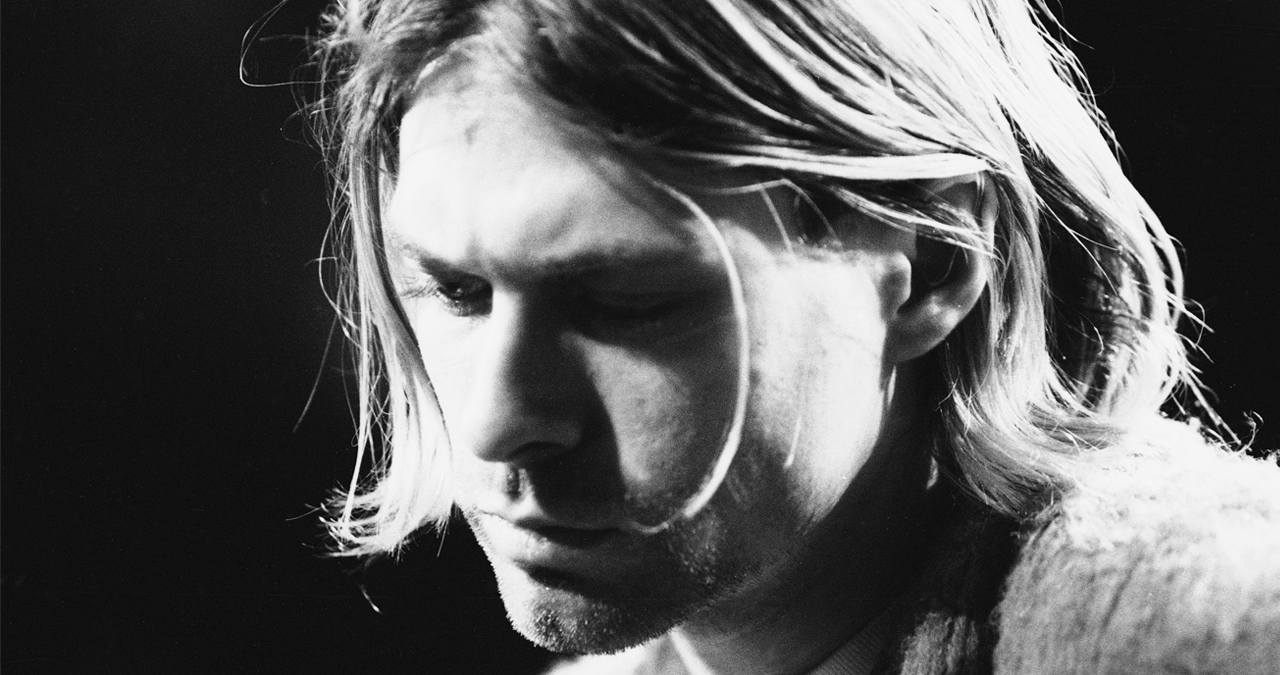

Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse all passed away at that particular age. While scientific research has disproven that 27 is in any way a statistically relevant age for the passing of musicians, the notion of ‘live fast, die young’ is persistent.

Musicians and other music professionals may not be statistically dying at that specific same age, but it does transpire that they are at an increased danger of an early death, with one study finding American musicians’ lifespans 25 years shorter on average than the general population. Alarming stuff.

Neil Young once sang that it’s better to ‘burn out’ than to ‘fade away,’ but this actually may be happening to musicians more frequently than they realise.

According to research, musicians are dying statistically earlier than the rest of society. An Australian study done in 2016 (titled, Life expectancy and cause of death in popular musicians: Is the popular musician lifestyle the road to ruin?) seemed to show that musicians who’ve attained popularity have shortened life expectancy.

Furthermore, it showed that overall mortality rates were twice as high compared with the population when averaged over the whole age range.

Interestingly, it found that mortality impacts differed by music genre, with excess suicides and liver-related disease observed in country, metal, and rock musicians, and - startlingly - excess homicides seen in six of the 14 genres, in particular hip-hop and rap musicians.

“This is clear evidence that all is not well in pop-music land,” said the author Dianna Kenny of the University of Sydney in The National, with findings indicating that American musicians die up to 25 years earlier than the general population based on seven decades of death records from 1950 to 2014.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Another study looked at mortality across a wider variety of musicians, including not just singers but also classical musicians and conductors. It found that rock musicians on average lived shorter lives than classical musicians.

The science is in: musicians tend to live less than the general population. But just what is it about musicians in particular that leads so often to an early grave.

MusiCares is an affiliate of The Recording Academy, the organisation that gives out the Grammy Awards, and supports music professionals with health and welfare needs. According to the organisation’s 2024 Wellness In Music survey, limited access to preventative healthcare services remains a major hurdle for those in the industry in the United States.

While 87 percent of survey respondents reported having health insurance (a figure close to the 93 percent national coverage rate), only about half have dental insurance because of the extra cost involved.

“Because so many music professionals work freelance or gig-to-gig,” says Theresa Wolters, MusiCares’ Executive Director, “access to comprehensive employer-sponsored healthcare is limited. Many do have insurance, but it’s often catastrophic or bare-bones coverage that doesn’t fully support ongoing or preventive care, such as dental, vision, or mental health services.”

This can cause music professionals to put off treatment until it becomes a major issue, which can lead to severe impacts on health.

For example, according to the survey data, 70 percent of people aged 45 and over missed recommended colonoscopy screenings, and 62 percent of female respondents aged 24 and older went without cervical cancer screenings.

“Music professionals are not accessing preventive health care and treatment services at the same rate as the general public,” continues Theresa. “Data from our Wellness in Music survey shows that 40-70 percent of people in music are not accessing routine, preventive care.”

Another issue that ties into the difficulties faced by music professionals is financial insecurity.

“Financial instability is deeply tied to the gig-based nature of the music industry,” explains Theresa. “Many music professionals rely on freelance or project-to-project work, which can be unpredictable even in the best of times. Work in music is also incredibly physically demanding for many roles, and vulnerable to so many elements that can affect a gig happening. For example, if the lead artist or a key member of the band gets COVID, that can result in the cancellation of a gig affecting dozens of individuals. Missing even one pay-check can mean missing rent, utilities, or access to basic necessities.”

More than just the loss of a pay-check, though, financial instability can have grave health consequences. “Financial instability and health are deeply interconnected,” notes Theresa. “Our survey data shows that 30-40 percent of music professionals attribute their stress and anxiety to financial issues. Chronic financial stress can significantly impact mental health, increasing anxiety, depression, and feelings of hopelessness. Over time, that mental strain can manifest physically, affecting sleep, immune health, cardiovascular health, and overall well-being.”

Particularly alarming is the prevalence of suicide within the industry. Kurt Cobain, Avicii and Ian Curtis of Joy Division are just three high-profile instances of musicians who took their own lives.

According to MusicCares’ survey, 8.3 percent of their respondents had serious thoughts of suicide in the previous year, a figure that is unfortunately higher than the 5 percent rate among the general population.

“The music industry can be incredibly rewarding, but it can also be isolating and emotionally demanding,” explains Theresa as to why this might be the case. “Music professionals often face intense pressure, irregular schedules, and long periods away from support systems, all while navigating financial uncertainty. When those stressors accumulate without adequate support, they can significantly impact mental health. What the survey underscores is not a lack of resilience, but a lack of systemic support.”

Academic research has also shown that suicide rates are high among music professionals. In fact, according to a 2025 study, musicians, actors, and entertainers rank among the five occupational groups with highest suicide mortality in the United Kingdom.

“The statistics are alarming - shocking,” said study co-author Dr George Musgrave in the Guardian. A sociologist at Goldsmiths, University of London. “The rates of suicide among musicians … paints a picture of a music industry which is demonstrably unsafe. No other industry would tolerate this level of loss of life and neither should we.”

The study also found high rates in the United States, with the arts, design, entertainment, sports and media category, which includes musicians, having the highest female suicide rate of any occupation group in 2012, 2015 and 2021. Men in the same category had the third highest rate, at 138.7 per 100,000 population, a figure that is almost 10 times higher than the national average.

“Multiple occupational and psychosocial stressors characteristic of music careers warrant examination,” says the study, “including exploitative industry practices, financial instability, heightened social media exposure, performance-related anxiety, internal achievement pressure, and irregular sleep patterns.”

Substance abuse has been an undeniable factor in a great many early deaths of many high-profile musicians, and can also be seen as a contributor within the broader study.

“Musicians as an occupational group have been seen to use illicit substances for various social, cultural and artistic/creative reasons, as well as exhibit higher levels of problematic drinking compared to non-musicians,” says Musgrave and additional author Dr Dorian Lamis in an editorial commenting on the study.

“Both alcohol and drug use disorders have been shown to be associated with suicide in empirical studies, and more work on this potential association among musicians is needed.”

Beyond just being a musician, fame itself has been shown to be a contributing factor to early death.

The study, entitled The price of fame? Mortality risk among famous singers ), conducted last year, discovered that famous singers had a 32 percent higher mortality risk compared with less famous singers.

“A 32 percent increase sounds dramatic because it is a relative number,” explains study co-author Michael Dufner of the Witten/Herdecke University. “Personally, I find a different metric more intuitive: on average, the famous singers in our study died about 4.6 years earlier than the less famous ones. That is a non-trivial difference, but it is not extreme. In terms of size, it is comparable to established risk factors such as light smoking versus non-smoking.”

According to the study, the results, “offer the strongest evidence to date linking fame with a higher mortality.” Some possible contributing factors suggested include increased stress levels, an unhealthy lifestyle, substance abuse, or a combination of these factors.

“Future research should try to disentangle these possibilities by taking factors such as childhood experiences, eating and sleeping habits, stress and drug abuse into account and by looking more closely at different causes of death,” says the study.

So, what can we do?

The data paints a bleak, and emotive picture. The particular industry-specific conditions that musicians and other music professionals have to navigate certainly seem to increase their risk of mortality. It’s far beyond time that we start addressing this problem.

Professor Dufner recommends targeted interventions: “Our findings suggest that elevated mortality risk among highly famous musicians may warrant increased attention to preventive measures. Potential interventions might include structured recovery periods during tours, access to mental health and stress-management resources, and programs designed to maintain social connectedness.”

Theresa from MusiCares recommends that music professionals themselves be aware of their own needs.

“Staying healthy starts with recognizing that wellness is not a luxury, it’s essential,” she says. “Prioritizing sleep, nutrition, and hydration while on the road can make a meaningful difference. Just as important is building in mental health check-ins, staying connected to trusted people, and asking for help early rather than waiting for a breaking point. Using available resources is a sign of strength, not weakness.”

To reduce the number of suicides within the industry, Dr Musgrave and his colleagues suggest that the industry adopt the seven-part approach provided by the Zero Suicide Framework framework, which includes calling on industry leaders to facilitate conversations about suicide prevention; encouraging training programs within musicians’ wider networks; identifying risk factors and warning signs; engaging those at risk of suicide with proven interventions; musicians maintaining care with providers when coming off tours; and continually improving “through data-driven research to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in this understudied occupational group.”

Sums up Theresa: “Longevity in music isn’t just about sustaining a career, it’s about sustaining a life. The industry thrives because of the people who pour their creativity, labour, and passion into it, often behind the scenes. If we want music to continue enriching our lives, we have to care for the people who make it possible. Supporting the health and well-being of music professionals isn’t optional, it’s essential to the future of music itself.”

If you’re a struggling musician or music industry professional, please reach out to an organisation like Help Musicians in the UK or MusiCares in the United States.

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.