“It made me want to write a song that, if it ever got back to the people going through those troubles, might just help them a little bit”: The intricate genius and powerful subtext behind a Beatles acoustic gem

At the very heart of the White Album, this tender Beatles masterpiece pulled from the classical music tradition and empathised with the American civil rights movement

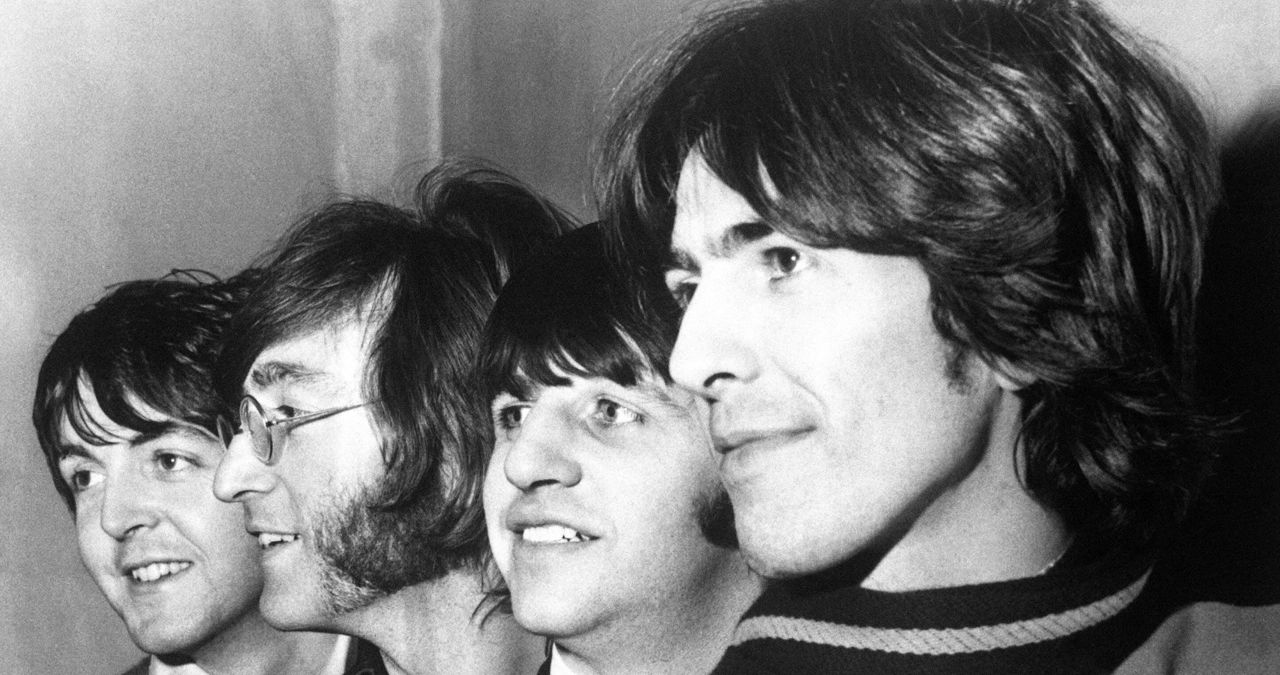

Bursting with some of the most audacious - and at times challenging - songs the Beatles ever recorded, the eponymous 1968 double-album (aka, the White Album) demonstrated just how far John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr had expanded the boundaries of contemporary pop.

It was also the album which most markedly revealed the now clearly distinct individuals the Beatles had become. Essentially creating music for the album as four (arguably three… with a floating Ringo - sorry Ringo) solo artists, the group still needed each other as vital competitors, casting their new outpourings into a contentious marketplace of potential Beatle songs.

The ‘let’s record everything you’ve got in one day’- production ethos that had been relied upon to track the bulk of the Beatles’ debut (amazingly, just five years prior in 1963) wad dead.

It had been replaced by a new notion. By 1968, albums weren't just documents of a beat combo's usual live set. They were now culturally significant statements.

In-keeping with the era's spirit of invention and disruption, the Beatles' new material needed to push and challenge conventions, as its trailblazing predecessor, Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band had established.

Although this double-album revealed an ever-widening gulf between these four men, it also underlined how fundamentally massive the Beatles had made their musical playground, by dent of their pioneering approach to songwriting and production.

The White Album contained tracks which draped themselves in the trappings of heavy blues rock, vaudeville, reggae, pastoral folk, brain-taxing avant-garde experimentation and even drunken saloon bar-piano. Pigeon-hole it if you dare.

In our opinion, the album’s greatest moment was an understated acoustic song, written and performed entirely by Paul McCartney.

It was called, simply, Blackbird.

In an album surrounded by themes that alluded to the fierce social divisions, fiery revolutions and looming dangers of the late 1960s, this tender assurance from singer to listener carried the torch of the Beatles' essentially positive spirit.

The basic idea for Blackbird stemmed from a classical guitar interpretation of Johann Sebastian Bach's Bourrée in E minor that Paul and George Harrison would often play together as teenagers, by way of flexing to their muso friends (and, we assume, impressing girls).

Similar to other notable McCartney cuts that had their origins in formative musical fun (When I’m Sixty-Four and Michelle, namely), this Bach-exercise formed the bedrock of Blackbird's wheeling central motif.

“It was kind of the beginning of a Bach piece, but nobody knew any better," McCartney said during an interview at Rollins College, Florida in 2014. "I don't know where it goes. It goes down a rabbit hole. So I took that and I made it [the beginning] of Blackbird. So, you know, you'd take these little discoveries and kind of just move them around a little bit to suit you because it was something you loved.”

It was during the Beatles’ legendary trip to Rishikesh, India to study transcendental meditation under the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi that McCartney was presented with the song's avian protagonist. Hearing a joyful blackbird call one morning, McCartney’s cogs began to turn.

Upon his return to the UK, safely back up in the well-stocked confines of his Scottish Farm, McCartney began to connect that moment, and his classically-inspired acoustic guitar exercise, with profoundly important events happening over the United States.

The civil rights movement's central drive towards freedom and liberty for black people was a globally-discussed concern. The movement had found support with many adjacent causes in the 1960s, many of whom were fighting for equality and social revolution.

Famously, the Beatles had insisted on performing only to un-segregated audiences during their three major US tours between 1964 and 1966.

Despite their insistence on playing to all, regardless of skin colour, Paul had witnessed first-hand a country riven with conflict over race, particularly in the southern states.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Naturally, McCartney (and the rest of the Beatles) wholeheartedly backed the civil rights movement, and felt that the new song could be a homage to those striving for a better tomorrow.

The ‘blackbird’ of this new song was blended with an idea of a black woman, fighting against seemingly insurmountable odds.

Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these broken wings and learn to fly

All your life

You were only waiting for this moment to arise

“This whole idea of ‘you were only waiting for this moment to arise’ was about, you know, the black people’s struggle in the southern states, and I was using the symbolism of a blackbird,” Paul told KCRW in 2002. “It’s not really about a blackbird whose wings are broken, you know. It’s a bit more symbolic.”

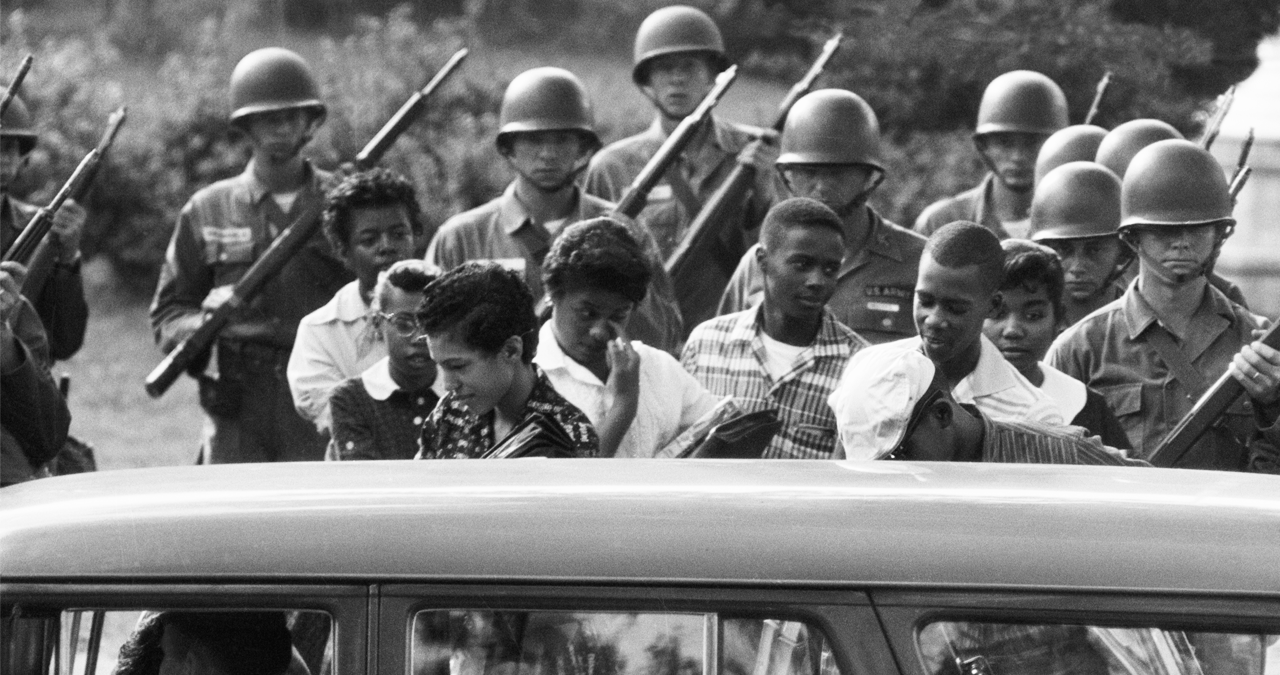

The specific black women (or black ‘birds’ - a deliberate, and slightly cheeky, British connotation that referred to a girl) that Paul had in mind were among the Little Rock Nine. These young black students had faced appalling racist abuse and discrimination when starting at the Little Rock Central High School in Kansas back in 1957.

This highly reported moment followed a US Supreme Court ruling that segregation in schools was unconstitutional. This caused uproar from some, namely Arkansas’ governor, Orval Faubus.

The boiling hot tension that the decision caused resulted in the students being escorted into the school by federal troops to deter the intimidation of protestors and the Arkansas National Guard, who had been summoned in by Faubus in an attempt to prevent the students gaining entry. This flashpoint moment shocked the world, and further galvanised the civil rights movement

“Way back in the Sixties, there was a lot of trouble going on over civil rights, particularly in Little Rock,” McCartney said at a gig in the city back in 2016. “We would notice this on the news back in England, so it's a really important place for us, because to me, this is where civil rights started. We would see what was going on and sympathise with the people going through those troubles, and it made me want to write a song that, if it ever got back to the people going through those troubles, it might just help them a little bit."

At that same 2016 show, Paul would meet two of those actual Little Rock students - Thelma Mothershed-Wair and Elizabeth Eckford that had been at the centre of those events.

Paul confirmed this historical milestone as being central to the inspiration of Blackbird. “Incredible to meet two of the Little Rock Nine,” McCartney said on his official Twitter in 2016, of these incredible women. “Pioneers of the civil rights movement and inspiration for Blackbird.”

A post shared by Paul McCartney (@paulmccartney)

A photo posted by on

Contextually, the true meaning of the song was likely also prompted by the recent assassination of civil rights movement-leader, Martin Luther King Jr, who’d been shot and killed in April of 1968 by James Earl Ray.

Paul’s arrangement of the song was based entirely around his laddering acoustic guitar part, in which just bass and treble notes, affixed together, moved simultaneously through the G major scale.

The ever-shifting shapes made by Paul’s increasingly contorted fingers gradually grappled their way down and back up through the scale before returning home to the G major root.

The way these dual-noted segments were played implied chords to the ear, but their voicing lent the song a fragmented, DIY feel which added to the song’s stripped-back intimacy.

It was how Paul played the piece on his right-handed Martin D-28 acoustic (strung upside down) that would be key to the song’s warmth.

McCartney’s thumb handled the bass notes and his fingers frantically picked - and intermittently strummed - the treble notes. Despite its classical inspiration, this peculiar way of playing the track lent a homespun, carefree vibe to Blackbird.

The time signature too was somewhat in flux. The first measure of the verse was in 3/4, while the second measure snapped into 4/4. Additional switches of time signature found Paul unashamedly snapping to 3/4 and then to 2/4.

The ungrounded time signature asserted McCartney’s complete control of the instrument - how he played it scanned to his words, and not the other way around.

McCartney illuminated the further inspiration of Bach when writing Blackbird, in his book Many Years From Now. “Part of its structure is a particular harmonic thing between the melody and the bass line which intrigued me. Bach was always one of our favourite composers; we felt we had a lot in common with him.”

After an initial recording session around at George Harrison’s Esher home using an Ampex four-track tape machine, the simple (at least instrumentally speaking) Blackbird was considered ‘done’ enough to be selected as the first Paul track to be recorded for the White Album. It would also be the first song finished for the record.

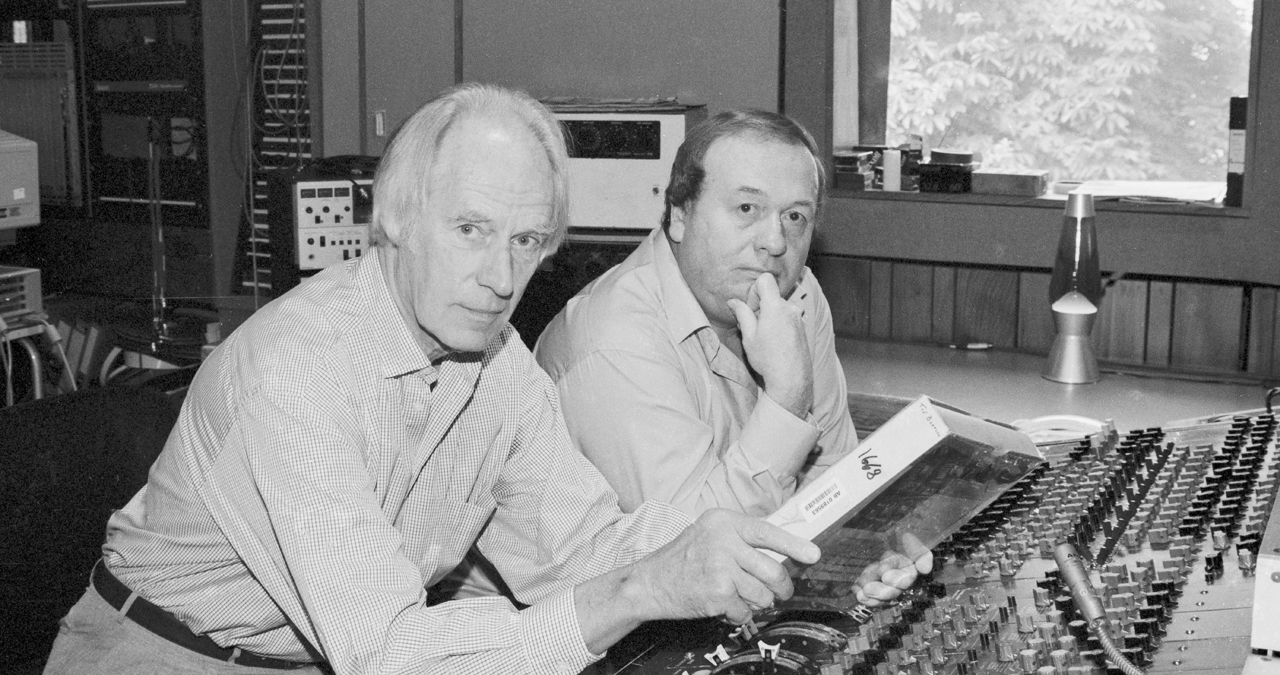

On June 11th, 1968, McCartney headed into EMI Recording Studios’ (aka Abbey Road) Studio 2 and worked with engineer Geoff Emerick and producer George Martin on tracking the song.

Meanwhile the rest of the Beatles worked in other studios on their own compositions. This siloed, 'personal project' attitude of each member would become commonplace as the White Album sessions progressed.

Engineer Geoff Emerick was struck by the song’s brilliance from the get go.“Playing his left-handed acoustic guitar, Paul began running the song down, and I loved it immediately,” Emerick said in his memoir Here, There and Everywhere. “Perfectionist that he was, he performed it over and over again, trying to get the complicated guitar part right all the way through.”

There was some deliberation on whether the acoustic-oriented song needed any additional instrumentation, but ultimately it was felt that the naked acoustic and voice arrangement was totally perfect.

It was George Martin who suggested the song stop abruptly ahead of the final verse, before coming back again - to emphasise the fluidity of the piece.

“Maybe on Pepper we would have sort of worked on it until we could find some way to put violins or trumpets in there. But I don’t think it needs it, this one,” McCartney told Radio Luxembourg in 1968. “You know, there’s nothing to the song. It is just one of those ‘pick it and sing it’ and that’s it. The only point where we were thinking of putting anything on it is where it comes back in the end, sort of stops and comes back in, but instead of putting any backing on it, we put a blackbird on it.

McCartney kept time with persistent alternating foot-tapping which would be captured on the recording, Geoff Emerick has stated that his foot was mic’d separately to ensure its presence in the mix (as, ostensibly, Blackbird's rhythm track).

Wanting the song to sound as if it were being recorded outside in a garden on a summer’s day, Emerick recalled in his book that he and Paul left the studio and found an area just outside of EMI’s echo chamber and captured a few more takes.

This is what, Geoff implied, imbued the song with the natural, open-air ambience that McCartney craved. This was further furnished with sound effects of birds from an EMI sound effects library record, although, Emerick claimed, a few real birds were captured during the recording that summer's evening.

It has been noted that this version of events has been disputed by engineer Ken Scott who insisted that final take of Blackbird was recorded in-studio.

Regardless of whether there was any genuine outdoor ambience captured, its undisputed that it took McCartney 32 takes (with 11 complete ones) before he was satisfied with it.

Paul would later double-track his vocal and finished the stereo and mono mixes by October 13th 1968.

Sitting in stark contrast to the instrumentally denser arrangements across the White Album’s 30-song journey, Blackbird was a meditative ocean of quiet, reflective calm.

Its not too-hidden subtext reflected McCartney's awareness of a responsibility the Beatles had to use their platform and influence to give voice - or demonstrate solidarity with - those in need. John Lennon was taking notes.

But, unlike the record’s other, more bluntly-stated treatise on the complexities of progress, Revolution, Blackbird’s strength is that it managed to convey a straightforward message of empathy and fundamental kindness without feeling overtly political.

Its compassionate spirit would resonate far and wide, connecting with both black listeners and doing much to stir deeper understanding from white listeners, many of whom were perhaps unaware of what was happening in America.

Widely regarded as one of Paul McCartney’s finest ever pieces of songwriting, Blackbird remains a crucial moment in his live shows to this day. With the now 83 year-old typically performing the song band-free, and being elevated increasingly higher above the crowd on a platform framed by a backdrop of glistening stars.

That might sound a tad cheesy, but it's a beautiful set highlight.

Blackbird has found its way to the ears of subsequent generations via covers from a multitude of artists, including Sarah McLachlan, Crosby, Stills & Nash and Dave Grohl, yet it’s undoubtedly the Beyoncé version that is most significant.

Her 2024, Cowboy Carter arrangement incorporated Paul’s original guitar part, and featured Beyonce’s lead vocal and four African American country singers backing her up. This gorgeous re-interpretation was masterful, and made its own uniquely significant statement.

Unsurprisingly, it thrilled McCartney himself.

“I am so happy with [Beyonce’s] version of my song Blackbird. I think she does a magnificent version of it and it reinforces the civil rights message that inspired me to write the song in the first place," McCartney stated on his social media.

"I think Beyoncé has done a fab version and would urge anyone who has not heard it yet to check it out. You are going to love it!”

McCartney continued, “When I saw the footage on the television in the early 60s of the black girls being turned away from school, I found it shocking and I can’t believe that still in these days there are places where this kind of thing is happening right now. Anything my song and Beyoncé’s fabulous version can do to ease racial tension would be a great thing and makes me very proud."

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.