“Writing a Bond song is a bit of an accolade. I always had a sneaking ambition to do it”: How Paul McCartney reunited with ‘the fifth Beatle’ George Martin to create the classic Live And Let Die

It was the first rock song to open a Bond film

One day in October 1972, Paul McCartney received a phone call from Ron Kass, head of Apple Records. McCartney liked Kass and they got on well. After chatting for a while, Kass casually asked McCartney, “You don’t have any interest in doing a Bond film, do you?”

It’s a moment recalled by McCartney in his 2023 book The Lyrics.

“Writing a Bond song is a bit of an accolade,” he wrote, “and I always had a sneaking ambition to do it.”

But in that moment he played it cool.

“I said, ‘Yeah, I’d probably be interested’,” he recalled, “trying not to seem too enthusiastic.”

Ron Kass knew someone in the Bond movie franchise and let them know that McCartney was interested. From that point on things moved quickly.

The screenplay for what would become the eighth film in the series wasn’t finished, but Kass told McCartney it was an adaptation of Ian Fleming’s second Bond novel, Live And Let Die.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The song that McCartney came up with was the first rock song to open a Bond film.

It was also a bold and audacious composition.

Live And Let Die would go on to become one of the greatest Bond theme songs, fuelling the success of the film and seriously upping McCartney’s standing as a solo artist.

The song reached No.2 in both the US Billboard Hot 100 and the UK singles chart, winning a Grammy and being nominated for Best Song at the 1973 Oscars.

For McCartney, it was a welcome commission and a song that is still a staple of his setlist over five decades on.

When Paul McCartney began work on Live And Let Die, he and his band Wings were nearing the end of recording their second album, Red Rose Speedway, the follow-up to the poorly received album Wild Life (1971).

The line-up of Wings at that stage featured McCartney and wife Linda alongside guitarist/multi-instrumentalist Denny Laine, lead guitarist Henry McCullough and drummer Denny Seiwell.

As soon as McCartney received a copy of Fleming’s book, he sat down and read the book in one day.

“It’s a real page-turner,” he recalled. “I just spent that afternoon immersing myself in the book, so when I sat down to write the song , I knew how to approach it.”

McCartney outlined the lyrical premise of the song in the 2013 biography Man On The Run. “I thought, ’Live and let die – okay, really what they mean is live and let live, and there’s the switch.’ So I just thought, ’When you were younger you used to say that, but now you say this.’”

He pushed on with this idea, playing on the phrase ‘live and let live’ in the evocative opening verse: “When you were young/And your heart was an open book/You used to say live and let live/But if this ever changin’ world/In which we live in/Makes you give in and cry/Say live and let die.”

Productive as ever, McCartney then wrote the song the following day.

“I think I read the book on a Saturday,” he recalled in the The Lyrics, “and I sat down at my piano in the living room and spent that Sunday putting it together.”

As chance would have it, producer George Martin had already been tasked with providing the orchestral score for Live And Let Die. This would be the first time since the recording of The Beatles’ Abbey Road album that McCartney and Martin had worked together.

“It was a joy,” wrote McCartney in The Lyrics. ”I showed him the chords and how the song was structured, and the central riff.”

McCartney already knew that he wanted explosions in the song but says he left the “Bondian” arrangements to Martin.

“His score was pure George,” McCartney recalled, “that perfect, stated balance of grandiose, without being over the top. I was very happy with that.”

In the 1982 book The Record Producers by Stuart Grundy and John Tobler, George Martin spoke about his collaboration with McCartney on this song. “It all started with Paul ringing me up and saying, ‘Look, I’ve got a song for a film. Would you produce it and arrange it for me?’ I said, ‘Sure,’ and spent some time with him at his house going through the thing, and from my point of view, we were making a record, so I didn’t spare any expense and booked a large orchestra.”

Martin knew from the outset that he wanted McCartney and Wings to be on the recording.

“I said, ‘This is the way we’ll do it – we’ll do it with Wings, and work on the session with just the group, and then in the evening I’ll bring in the orchestra, but we’ll still keep Wings there, and try to do it live altogether, to try to get a live feeling to it.’ And that was what we did.”

It was an inspired decision. The live performances by the band and the orchestra are what gives the track real dynamism.

“It was at AIR Studio, with the orchestra live in the room with us,” Denny Laine told Bill DeMain of Guitar World in 2023. “We captured the excitement of a performance, which I think is why the record was so powerful.”

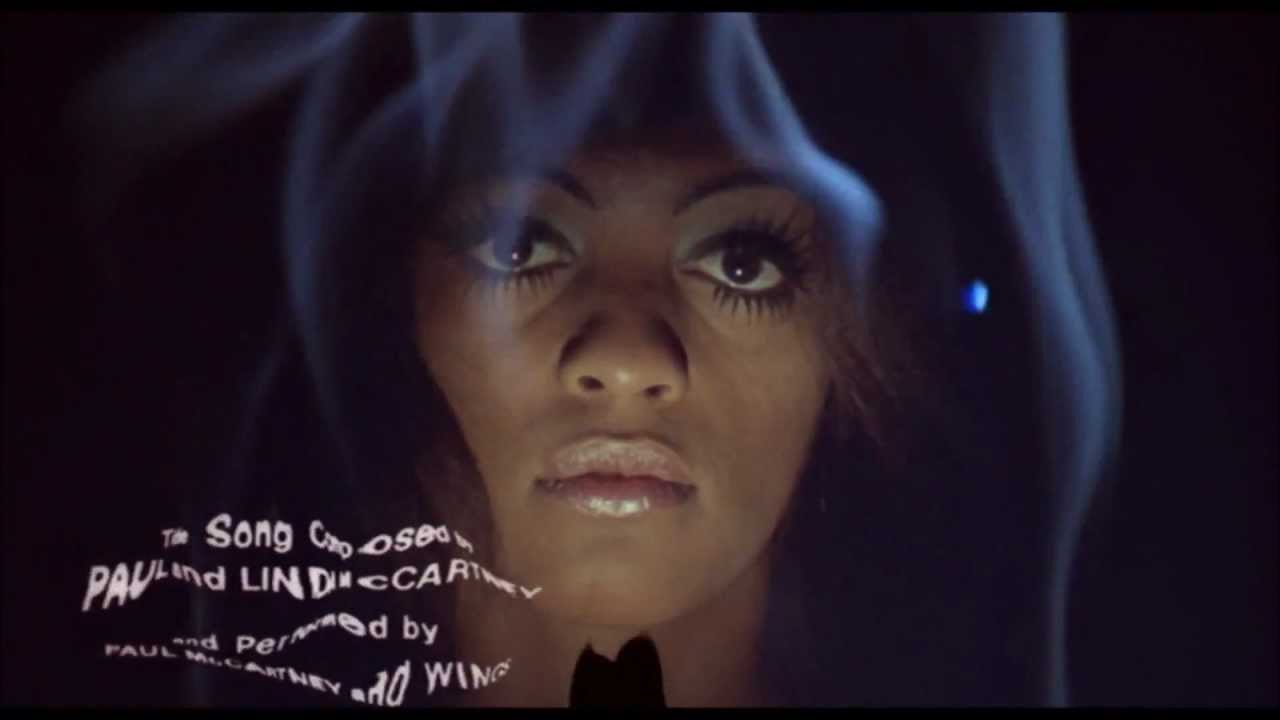

The Live And Let Die film ushered in a whole new era for the Bond franchise as it was the first to feature Roger Moore in the starring role. Fittingly, McCartney’s theme song also marked a significant change and featured dramatic shifts in style and pace.

The song opens with plaintive piano chords, and there’s a rich fullness to McCartney’s voice, which sounds double-tracked but isn’t.

It’s a simple ascending chord structure – G-Bm7-C-D7(b9) – with a soft, reflective mood, which shifts dramatically 33 seconds as the full-on bombast of the orchestra and Henry McCullough’s Les Paul kicks in.

At 0:47, the whole track breaks into a 150bpm instrumental gallop, with strings delivering the song’s iconic staccato motif, before trills of flute and Ray Cooper’s skilful percussion bolster the frenetic, driving pace.

At 1:21, the track drops suddenly to just Wings, playing a lilting reggae groove. This middle section of the song was written by Linda McCartney on the same Sunday in October 1972 that Paul created the song at the piano. The nod to reggae is apt, given the Jamaican locations in the film.

At 1:36, the full heft of the orchestra re-enters the mix, before the song returns to McCartney’s verse structure, as a beautifully emotive violin part emulates his top line vocal melody.

McCartney then delivers the second verse and at 2:21, on the word “die” the massive orchestral stabs strike up again.

Then, it’s more of the instrumental gallop right through to the end, with George Martin’s brilliant, sweeping string arrangements building in intensity up to the closing crescendo and fade.

The whole song lasts just over three minutes, but it packs in a whirling, giddy rush of styles and emotions, while exuding all the drama and action-packed fizz and excitement you would expect from a Bond theme song.

In his 1979 memoir, All You Need Is Ears, George Martin recalled playing an acetate of the recording to Harry Saltzman, who co-produced the Bond films with Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli. Martin was not expecting what came next.

“He sat me down and said, ‘Great. Like what you did, very nice record, like the score. Now tell me, who do you think we should get to sing it?’

“That took me completely aback. After all, he was holding the Paul McCartney recording we had made. And Paul McCartney was… Paul McCartney.

“But he was clearly treating it as a demo disc. ‘I don’t follow. You’ve got Paul McCartney,’ I said. ‘Yeah, yeah, that’s good. But who are we going to get to sing it for the film?’ ‘I’m sorry. I still don’t follow,’ I said, feeling that maybe there was something I hadn’t been told. ‘You know – we’ve got to have a girl, haven’t we?’”

The idea that the producers wanted a female voice such as Shirley Bassey or Thelma Houston rather than Paul McCartney is a view that has been widely reported and backed up by McCartney himself over the years.

But in their 2022 book The McCartney Legacy Volume 1: 1969-1973, writers Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair unearthed research that suggested the producers always wanted McCartney from the very start.

Sinclair noted that the archival material – internal communications between lawyers and others representing McCartney and the Bond producers, Eon Productions – “undermines the story and shows it in a very different light”.

One of the documents is from Ron Kass to Harry Saltzman at Bond producers, Eon Productions. This stated that “Paul McCartney has agreed to write the title song entitled Live and Let Die. He and his musical group Wings will perform the title song under the opening titles.”

“So we can pretty definitively say that they were not going to replace Paul,” said Kozinn. “One of the versions was going to be with Wings, which would play over the opening titles of the film and the closing credits. There would be a live version of the song performed during the club scene by BJ Arnau, a soul singer. When we saw those documents we couldn’t help but think it was just a misunderstanding.”

Live And Let Die would help revitalise Paul McCartney’s creative standing and would soon be incorporated into Wings’ live setlist.

Critics by and large lauded the song. A retrospective review in Billboard concluded that it was “the best 007 movie theme” and one of McCartney’s most satisfying singles. Cash Box, another music industry trade magazine, said the song was “absolutely magnificent in every respect”.

Ian MacDonald of NME was less enthused. “It's not intrinsically very interesting, but the film will help to sell it and vice versa," he wrote.

For McCartney, Live And Let Die plays a prominent role in his post-Beatles back catalogue and in his live set.

“It’s still a big show tune for us to this day,” he wrote in the conclusion of his entry on the song in his book Lyrics, adding that he still likes watching responses on the audiences’ faces when the pyrotechnics kick in.

18 years after its release, Live And Let Die re-emerged in the charts as a cover version, going on to reach top ten in nine countries.

“Guns N’ Roses did a version of it,” recalled McCartney, “ and the interesting thing was that my kids went to school and said, ’My dad wrote that’ and their friends said, ‘No, he didn’t. It’s Guns N’ Roses!’ Nobody would believe them.

“But I was very happy that they’d done it. It was a pretty good version actually… I always like people doing my songs. It’s a great compliment.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.