Sunroof: "We needed to move away from doing 45-minute rambling jams"

Danny Turner reveals how the iconic producers’ modular jams finally came to fruition

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sunroof duo Gareth Jones and Daniel Miller have finally released their debut electronic album 40 years after they first became friends.

Gareth Jones, famed for his production work for Depeche Mode, Erasure and Einstürzende Neubauten, first became acquainted with fellow producer/label boss Daniel Miller when requested to work on Mode’s 1983 synth-pop album Construction Time Again. At the end of those sessions, Jones and Miller would stay behind and playfully experiment with sounds at The Garden – then studio of synthesizer pioneer John Foxx.

Despite naming the project Sunroof and later remixing artists including Goldfrapp, Can and To Rococo Rot, the duo refrained from releasing their own studio jams for almost 40 years. However, that changed in March 2019 following various improvisations using modular suitcases. This time they made plans to record their sessions, resulting in Electronic Music Improvisations Volume 1 – eight extemporary modular pieces recorded live in various studio spaces across London.

Can you remember the circumstances behind the two of you first meeting?

Daniel Miller: “We were starting to plan working on the third Depeche Mode album Construction Time Again. Up to that point we’d been working at a great studio called Blackwing but felt we needed a change of scene so finally landed at John Foxx’s studio The Garden because it was so different from a conventional studio.

"It had daylight, which was unusual in those days, a relatively big control room and a small live room, but we didn’t have an engineer. John suggested Gareth because he’d help set up his studio and worked with him on Metamatic.

"Gareth had a very enthusiastic vibe, so we decided to work with the Mode together and it all became very natural and fluid with a lot of experimental processes.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Gareth Jones: “In a way that was the start of the Sunroof project because, quite quickly, Daniel and I realised that we liked hanging out in the studio after Depeche Mode had gone home.

"They usually got the train back to Essex and as we were both living in London we’d spend the odd hour or two doing jam sessions and playing around with synths and effects. We were just mucking about and wouldn’t even record them, but this improvisational record grew out of those early seeds so they were useful.

DM: “We worked very intensively with the band so it was a good head-clearing exercise and we both had our own modular synths at the time. I had an ARP 2600 and a Roland System 100M, so we were already in that world.”

How would you compare the electronic music scene now to how it was back then in terms of the availability of instruments?

DM: “Electronic music in the broader sense had been going on for years before that with Stockhausen, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and producers like Joe Meek who were using strange effects. Unless you could build your own synths, which I wasn’t capable of doing, making electronic music was a distant dream, but before the second half of the ’70s the tools became a lot more accessible.

"There’d been some Japanese releases from Roland and Korg especially, and they came on the second hand market and were already a lot less expensive than the Moogs and the ARPs. For a young band, the only option was guitar, bass and drums, but now there was a new option so it was all very exploratory.”

GJ: “Another thing that was super-important was the availability of relatively cheap multi-tracks. You could save up your fruit picking money and buy a four-track, which was massive. When we were working with Mode we obviously had a big 24-track in the studio, but for DIY electronics – like Sunroof – multi-tracks were a big thing too.”

DM: “It was the beginning of the accessibility of electronic instruments, which over the last 40 years has exploded in so many different ways. It’s a lot easier now I suppose, which means quite a lot of the music out there is good but not unique, even if some of the instruments are being used in really new and creative ways.”

In those early days the sound was new and driven by the technology. Is it much harder to stand out today?

DM: “It’s harder to stand out for the reasons you said but also because there’s so much music being released now. I think Spotify has 60,000 releases every week, but it’s not just about the sound, it’s about expression and how you use those instruments. Paint has been around for hundreds of years but people are still painting and creating unique and expressive work.”

GJ: “Photography too, which is a good parallel to electronic music. Everyone’s a photographer now, but there are still truly great images that stand out.”

By the mid-‘90s you’d developed Sunroof as a remix project…

GJ: “I particularly remember doing a wonderful remix for the Can track Oh Yeah, which appeared on their Sacrilege remix album. We were invited to do a number of others for Pizzicato Five and Kreidler, which were largely to do with Daniel’s profile at the time.

"I moved back from Berlin in the early ’90s and Daniel was setting up his home studio. Over many weekends I’d help out, muck around with his synths and gradually turn it into a more integrated and coherent setup. Part of that process was doing a bit of tech work and part of it was doing a series of extended jam sessions the length of an ADAT tape.”

Why didn’t you release anything?

GJ: “We didn’t think the tracks were releasable because they were too long and rambling and we never quite got the motivation to edit them down into bite-sized pieces. I guess we were both very busy in our day jobs.”

DM: “The jams that we did in those days ended up on SoundCloud much, much later on. We didn’t promote them; they’re just there if anyone finds them, so I wouldn’t call them a release really.”

Was Electronic Music Improvisations Volume 1 a result of previous recordings or did you want to start with a completely clean slate?

GJ: “We literally started with a clean slate because one of the things we did was to meet up with our portable modular cases with nothing patched up. One of our rules was that we wouldn’t prepare, although I guess we’d already had 40 years preparation of making music together.”

DM: “All of our experiences of working together in various ways fed into what we did, so we just started building patches and ran a master clock between the two systems. When we had something that we thought sounded OK we’d press play and record.”

You were inspired by recent works by Chris Carter and Martin Gore. Presumably that relates to their recent modular-based albums?

GJ: “We needed to get in the right headspace and move away from doing 45-minute rambling jams and decided they wouldn’t be jams but coherent improvisations with a five or six-minute arc, which was hugely inspired by Chris and Martin’s work.”

Daniel mentioned using portable modular suitcases, so the recordings took place in London but not always at your own studios?

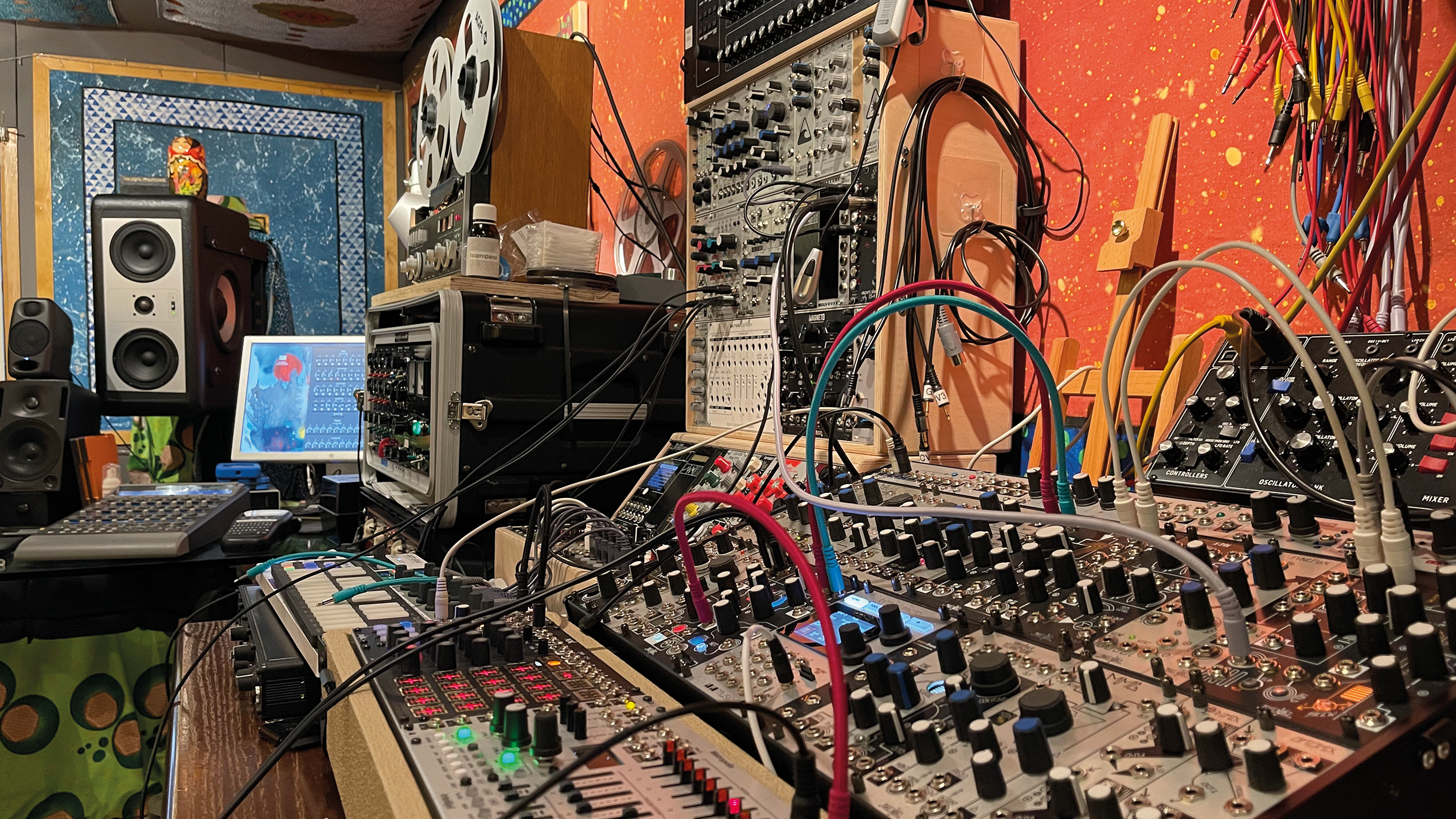

DM: “We recorded at Gareth’s studio and the Strongroom Music Studio where he’s based, my studio at home and the Mute studio, but we stuck to just using our portable 7U 104HP Intellijel cases.

"We recorded as live with two stereo outputs from our systems straight to the DAW, but we only played for five or six minutes because we didn’t want it to be an editable performance. Once you start editing you lose that natural flow.”

GJ: “We did the simple thing of making the Ableton Live window six minutes across and didn’t glance at it much. Even though you zone out when you’re improvising, you quickly get a feel for how long five or six minutes is, so when the cursor got to the right-hand-side, we pressed stop. I want to underline that not every improvisation worked – we didn’t use about 50 per cent of them.”

DM: “We did a couple of minor tweaks afterwards but, basically, there’s no post production other than adding one bass part.”

We recorded as live with two stereo outputs from our systems straight to the DAW, but we only played for five or six minutes because we didn’t want it to be an editable performance. Once you start editing you lose that natural flow.

Is setting limitations the key to being productive with modular equipment?

GJ: “That’s the key to being productive in life. I used to be terrified of deadlines and limitations because it always seemed like an enormous stress, but now I welcome limitations because I know that they help me to be much more creative.”

DM: “Those things are really important if you want to finish something. One of the joys of modular is that 90% of the time I’m only doing it for myself – then you get lost and it becomes a very personal experience of being in the studio, finding and living with sounds. Having fun can also be meditative.”

Gareth, you mentioned limitations making you more creative but one might also imagine them inhibiting a person’s creativity?

GJ: “There are so many possibilities now with software and laptops that, in the third decade of the 21st century, limitations are more helpful than they were back in the ’70s. John Foxx taught me something really good about his approach to art.

"When I had the pleasure of making Metamatic with him, he wanted to make a minimal album so he went into an 8-track studio with one drum machine, one string synth, a flanger and a little sequencer. He used a minimal toolkit in a minimal studio to make a minimal record and in retrospect I’ve realised how those kinds of limitations really helped him to focus.

"It’s like football isn’t it? You play it on a pitch - you don’t play it across London. On the pitch there’s a limitation – the ball’s either in or out, so there’s rules.”

DM: “When you’re painting you have a canvas – nobody talks about that being a limitation. ‘Limitation’ is a slightly pejorative term – setting your own guidelines or boundaries might be a better way to frame it.

"You’d think of it as a limitation now, but when I got my first TEAC four-track it was liberating – suddenly I could overdub, which was mind-blowing at the time!”

Throughout the recordings, how did you avoid stepping on each other’s toes?

DM: “There wasn’t any treading on each others’ toes – you get to a point where you’re listening to what you’re doing and what the other person is doing until you don’t know who’s doing what [laughs]. That’s pretty exciting.”

GJ: “We had made a point to not discuss what we were doing. We’ve obviously been friends and colleagues for a very long time, so we chatted when we met up but not about the music and we didn’t listen to any of it until we felt we’d collected enough pieces to sit back and listen to them all. That was part of the manifesto.”

Daniel, you’ve previously mentioned that you like to leave time before revisiting a recording. What’s the benefit?

DM: “Whenever you create something, it’s not just about the music but the space you’re in, for example, did you get up on the wrong side of the bed or have an argument that day?

"I feel that we need to get distance from all those different personal emotions or experiences and try to judge music on a more objective basis. People who use analogue photography might not look at their pictures for six months for the same reason, so it’s quite useful.”

As producers, do you therefore encourage other artists to detach themselves from whatever they’re creating?

DM: “As an A&R person I’ll sometimes come into a session with a band and say, ‘that hi-hat pattern’s a bit busy’, and the artist might say, ‘well I spent days on that’, and I’d say – in a nice way – ‘as a listener it doesn’t sound very good’.

"I don’t know the circumstance of how a kick drum or vocal was recorded – all I know is what I hear and that’s a very important part of the process. It was the same when we were making records with Depeche because a lot of the time we’d spend hours trying to create a sound, get attached to it for all the wrong reasons and lose perspective in terms of if it was any good.”

GJ: “I’m my own worst critic. I very much enjoy painting with watercolours but as soon as I finish a painting, I judge it immediately and always think it’s not that good. But that doesn’t mean anything – it’s just the inner critic shutting me down, and spending time away from your creation is a way to defeat the inner critic.”

Gareth, have you noticed the artists you produce shifting from computers to more physical, improvisational-based tools?

GJ: “As Daniel flagged up, people are so different – some are very hands-on and some like recording to tape, so it’s a broad church out there. I’m old-school and like physical hardware because it allows accidents to happen and in my world that can be extremely productive and fruitful.

"When I’m only working in digital it seems harder for creative accidents to happen and that’s a pity. That’s one of the great things about us working in the same room for the Sunroof project and so many other truly creative projects, because when you’re together your ‘mistake’ might be the other person’s favourite bit, and that changes everything.”

DM: “You can fix accidents in digital whereas you can’t in analogue. You might think, oh shit, I made a mistake there and fix it, but had you left it in, a few days later you might think, wow, that was good, how did that happen?

"The people I work with generally want to work outside of the box and use the computer purely as a tape recorder. They don’t want to use software instruments, pre-prepared samples or go menu-diving.”

Would you say that many electronic artists today are also looking for a certain uniqueness of sound?

GJ: “Yes, because you’re forced to commit - that’s what’s so great about it. I make loads of sounds on my Eurorack but I’m not sufficiently skilled to reproduce them, so it’s a one-off thing that either works on a piece or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t work, you have to make something else.”

DM: “It’s kind of like going back in time as well. When I started there was the Prophet and a couple of high-end synths but the stuff I was working with had no presets or memory and I think that’s so productive. Now I see sessions with 130-140 tracks, which is ridiculous.”

Does it really need to take three or four years to make an album, which is quite common now?

DM: “There’s two different parts to the question you’ve just asked, one is to write and one is to record. Songwriting can take a while because it’s a very personal and specific process – some can do it very quickly and others take their time, but the recording process doesn’t have to take four years. We made our record in about 20 hours of studio time.”

GJ: “And I’m putting my money where my mouth is because I’m about to produce a record with an artist where all the songs are written and we’ve allocated a 15-day recording process because we want to constrain ourselves.

"We feel the songs are there so we’re just going to go in and make the record. It’s obviously not for everyone, but I’m committed to trying to work faster because it’s so wonderful when you get on a roll and surf that wave.”

Where’s the most innovation coming from in the modular world?

DM: “I have my portable travel case, which serves a number of purposes for me depending on whether I’m asked to go to a studio to help out with a few overdubs, play live or go away on holiday and mess around with it.

"I probably should, but I don’t define the case by what I’m going to do with it, so I didn’t change anything for these sessions with Gareth – I’m very lazy about plugging and unplugging modules into the system.”

GJ: “Same here, I just made it up as I went along really, but there are some items that are core parts of my performance element. The Make Noise René synth module and their Pressure Points analogue sequencer, which allows me to modulate a patch and when you let go of the pressure points the sound goes back to where it was – that’s been transformative for me. I also used the TEMPI module for clocking.”

DM: “For me it was the Five12 Vector digital sequencer, and also the little Eurorack Befaco mixer, without which I don’t think I’d have been able to do what I did because it’s got sends, returns, EQ and six channels, which makes things much more performable live.”

GJ: “There was a great complementarity there, and I just want to give a quick shout out to Make Noise. I’m not sponsored by them in any way, but I’ve become a huge fan of their equipment and philosophy, and that engagement has been part of my unfolding creativity with Eurorack.”

Daniel, we understand you’ve been involved in designing some modules of your own?

DM: “I’ve been collaborating with Future Sound Systems on a couple of modules because I wanted to be able to easily make quite big changes during a live set without re-patching or trying to turn lots of different knobs at the same time.

"They’d already collaborated with Chris Carter on The Gristleizer, which was great, so we created Mute MAKROW which has got six CV outs and one knob that controls of all those different outputs. You can have one CV going to an effects mix, an LFO speed or a filter sweep, so all of a sudden you’ve got control over many different adjustments at once, which is really powerful for using live.

"The other module is called STUMM, which basically has six mute switches. There’s lot of really good muting modules out there, but this one can group the mutes, so if you’ve got a kick drum, hi-hat, snare drum and percussion and want to drop three of those instruments out, you can do it with one switch.”

GJ: “I remember when Ableton introduced their Macro function and how taken Daniel was with it. He’s made a hardware version of something we first discovered together in software, which I think’s great. I’ve always been nuts about samplers for making my own sounds and more of those are emerging in Eurorack so I’m dipping my toe in and experimenting with that now.

"I’ve got a Bigbox Micro and find that all this digital stuff with hands-on control inside the Eurorack is super-interesting. When samplers were invented it was so much fun and I’m always trying to get back to that.”

DM: “In the same way that Gareth has always been a sampling nut, I’ve always been a sequencing nut. My first sequencer was an ARP 1603 and I found that such an unbelievably creative tool.

"As I mentioned, the Five12 Vector module is so great because it’s very immediate if you want to do the ARP sequence type of thing, but incredibly deep in terms of doing weird timings etc if you want to go there.”

Electronic Music Improvisations Volume 1 obviously indicates there will be a volume 2?

DM: “We called it Volume 1 because we thought it would give us a spur to do Volume 2, but then lockdown happened and Gareth suggested that we try to do something by exchanging files. I found that really difficult because working remotely is such a different process and I couldn’t really get my head around it. As soon as we can get back together I’m very excited about doing some more pieces.”

GJ: “I’m sure if this terrible virus hadn’t raged there would be another bunch of recordings already because our whole musical life together has always been about improvising and jamming and now we’ve got more of a reason to do it.

"Our physical meeting place won’t be the same because we feel it’s very important for us to work in a different space every time. We’ve touched on the idea of going battery powered, so we could make music in the park, the woods or on the tube. Obviously, the pressure of a second album will be a bit heavy, but hopefully we’ll get through that.

DM: “The pressure’s good in some ways. We’ve both developed our techniques and maybe that will be reflected in what we do next. Our massive audience is waiting with huge expectations [laughs].”

Sunroof’s Electronic Music Improvisations Volume 1 is out now on Parallel Series.