"I started hallucinating whispers that weren't part of the composition - it was intense": Maria W Horn on spectral synthesis, recording in a former prison and her love of SuperCollider

Through instrumental textures, room responses, the human voice and a specialised computer language, Maria W Horn explores sound's spectral properties. We heard more about her processes and the chilling story behind her affecting new album, Panoptikon

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

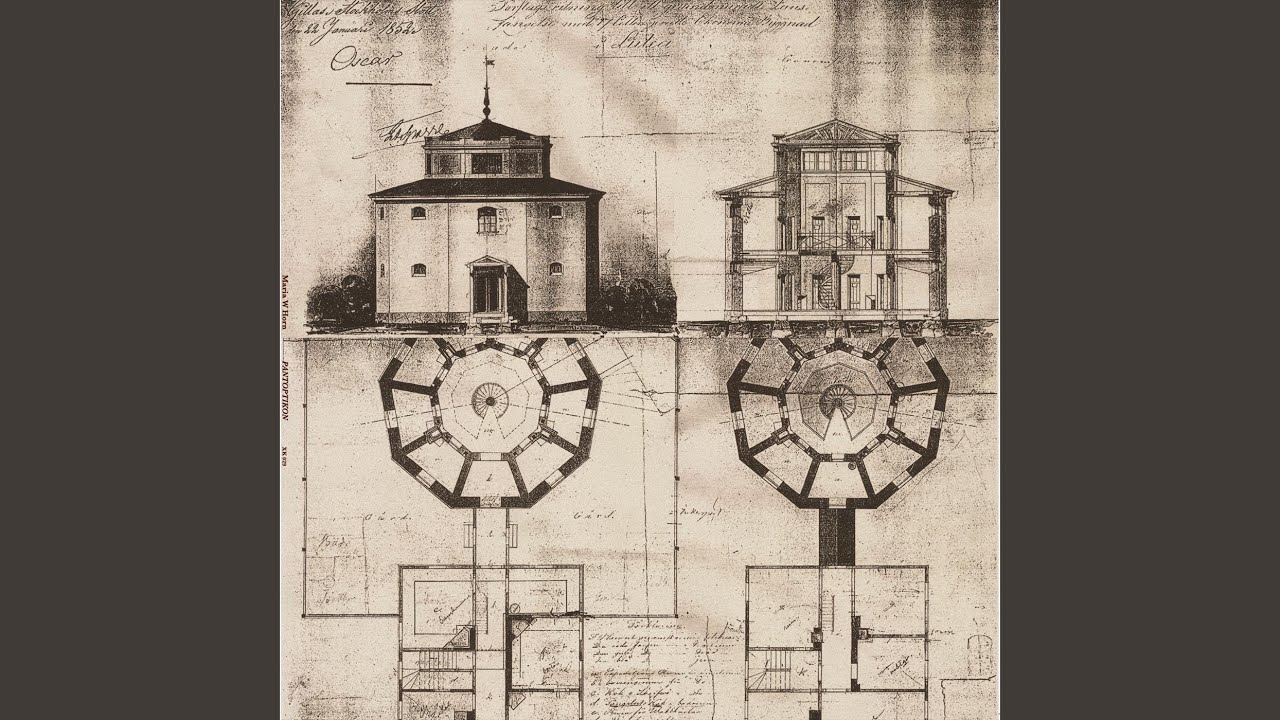

Originally operational between 1856 and 1979, Sweden’s Vita Duvan prison, in Luleå, in the far north of Sweden, was the country’s only ‘panopticon prison’: an environment designed to facilitate maximum social control through psychological techniques, including isolation and limited human contact.

It instilled an omnipresent feeling of being watched via its circular structure. For Swedish composer, artist and electronic innovator Maria W Horn, the prison – now abandoned – was an intriguing prospect.

Maria explains: “As I visited the city in order to research the area for The Arts Biennial, I passed by this circular building that I found fascinating. It turned out to be a former prison. The only ‘panoptic’ prison in Sweden. As I started working on an installation, the history of the prison gradually unfolded.”

Sonic projects of this type are nothing new for Maria: her 2021 work Dies Irae, for example, focuses on the acoustics and spectral properties of an abandoned machine hall. The Stockholm-based composer is a well known figurehead of the city’s experimental electronic scene, which was underlined by her co-founding of label XKatedral in 2015.

Operating at the intersection between audio/visual art and working as a music artist, Maria’s latest project was spurred by a fascination with the lives of the people who were held at Vita Duvan. “In this work, I was trying to imagine the experience of the individual prisoner, whose first three years were often spent in total isolation, during which all contact with other prisoners was strictly forbidden.

“The silence and uncertainty, the scarce space whose only indication of the passage of time, is the cycles of daylight. How is consciousness affected by the kind of sensory deprivation that an isolation cell entails?

“One passage from the prison books that stuck with me was describing the church service held on Sundays, where the priest was located in the middle of the panopticon and prisoners were allowed to have their doors hatched slightly open, to hear but not see through the cell doors.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“In this way they could sing along with the hymns from inside their cells, and this is described as a very intense and vivid experience for the inmates, after months of isolation, to get to hear the voices of the other inmates and to share this communal singing experience. This was only allowed for a brief period in the prison’s history, as the management believed that the risk was too high that the prisoners could transmit secret messages to each other through the songs.

“I wanted to focus the piece around the idea of vocal transmission echoing through a structure built for psychological surveillance. The individual voices of the inmates are represented by their voices distributed by loudspeakers placed in each prison cell. What if I could use this emotive image and expand it into a vocal cycle? An imaginary choir comprised of ghosts of the Vita Duvan prison.”

Hearing voices

Maria refers to her music as spectral, which in part refers to the ideas derived from the 1970s French minimalist music tradition where the composer’s artistic choices are based on the harmonic spectrum of the instruments. With the use of electronic technology, this approach can be used to capture the acoustic properties of a room, a technique that Maria used in the prison.

“For the last couple of years I’ve been focused on site-specific composition. An interesting way to adapt the music to a building is to measure the acoustics of the room. I’ve been making IRs [impulse responses] of different spaces and then used these imprints for spectral analysis. This way I can find out about the resonant frequencies of a building, and use the specific resonance or grits of the acoustics to tune the harmonic universe of the composition.

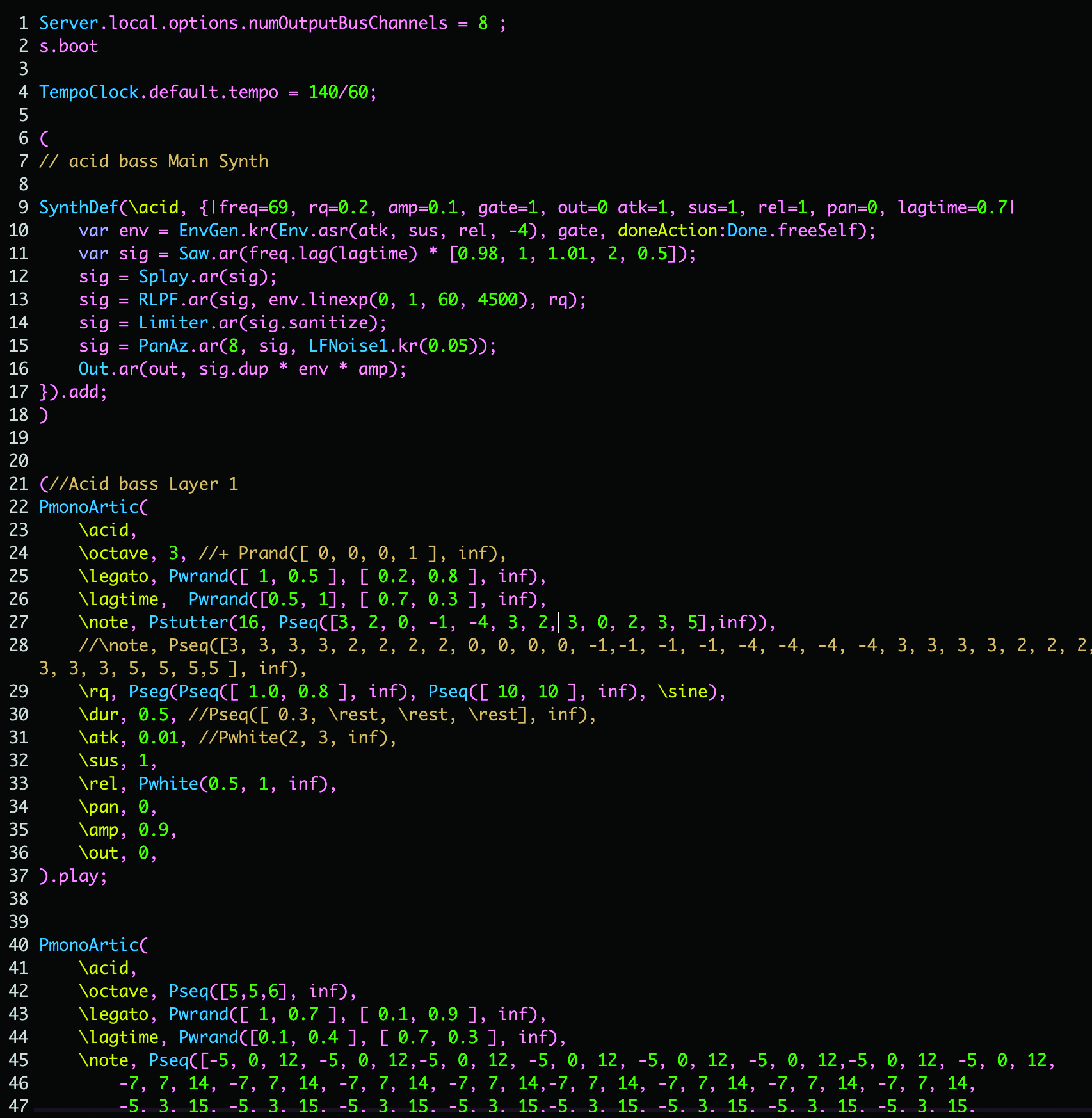

“I’m using a program called SuperCollider which is a musical programming environment that allows you to program your own synthesis. The good thing is that you can achieve precise control of tuning, texture and timbre when you operate on this level of signal processing. As a starting point for a composition, it is a powerful tool, and the level of customisation allows for very personal synthetic sounds.”

Hearing those voices constantly made me hallucinate whispers that weren’t part of the composition. It was intense

Maria continues: “Essentially Panoptikon is part of an ongoing musical research of site-specific composition techniques, but there’s also an emotional aspect that deals with memory and the idea that events and emotions create inherent memories in a building, object or instrument, and that these ‘traces’ or ‘ghosts’ are available if we’re willing to listen.”

With the prison’s spectral properties captured, Maria began thinking about the musical components within the concept of Panoptikon. “I wanted the piece to have an underlying grid of some sort, so I came up with a 14-chord sequence that runs throughout the whole piece. For the installation, it was in sync with lights, fading in and out, as a way to reflect the passage of time and cycles of daylight in the imagined experience of the inmates. There’s a static element to these recurring chord blocks, monotonous just like the days of a prisoner.”

On top of this chordal grid, there’s the recorded vocals of the four singers [Sara Parkman, Sara Fors, David Åhlén and Vilhelm Bromander] adding melodies and ornamentations, lamenting the passage of time. The resulting tracks; Omnia Cittra Mortem (which translates as ‘Everything Until Death’) Hæc Est Regula Recti and Längtans Vita Duva are truly affecting pieces. These tracks capture a sense of timeless desperation, fading hope and a longing for human communication. A theme which had further unexpected resonances in 2020 when the installation was first active.

The singers themselves never actually set foot in the prison itself. “I recorded the singers separately, as I wanted to be able to spread and isolate the different voices to the various cells of the prison. The actual setup of the installation within the prison was quite demanding.

“Me and my partner Mats Erlandsson built the installation in winter of 2020 during the Covid pandemic. In December in the north of Sweden there’s around an hour of sunlight a day. Due to Covid restrictions, the Biennale didn’t want us to meet anyone. So in a way, we were isolated in the prison for two weeks. I went a bit crazy during that time.”

The intensity of both Covid and developing the prison installation in tandem, put Maria in a state of mind not too dissimilar to the prisoners themselves.”We had to keep running the installation constantly to make sure it all worked. It was due to be there for three months and we had to stress-test it. Anyway, hearing those voices and whispers constantly made me start hallucinating other voices and whispers that weren’t part of the composition. It was quite an intense experience.”

Acting on impulse

Amazingly, all of the instrumental elements on the record (including an omnipresent low frequency hum, the shifting, pulsing chord cycle and a weaving organ-type sound) were developed using algorithmic musical programming, synthesised with inspiration from the odd acoustic properties of the building itself.

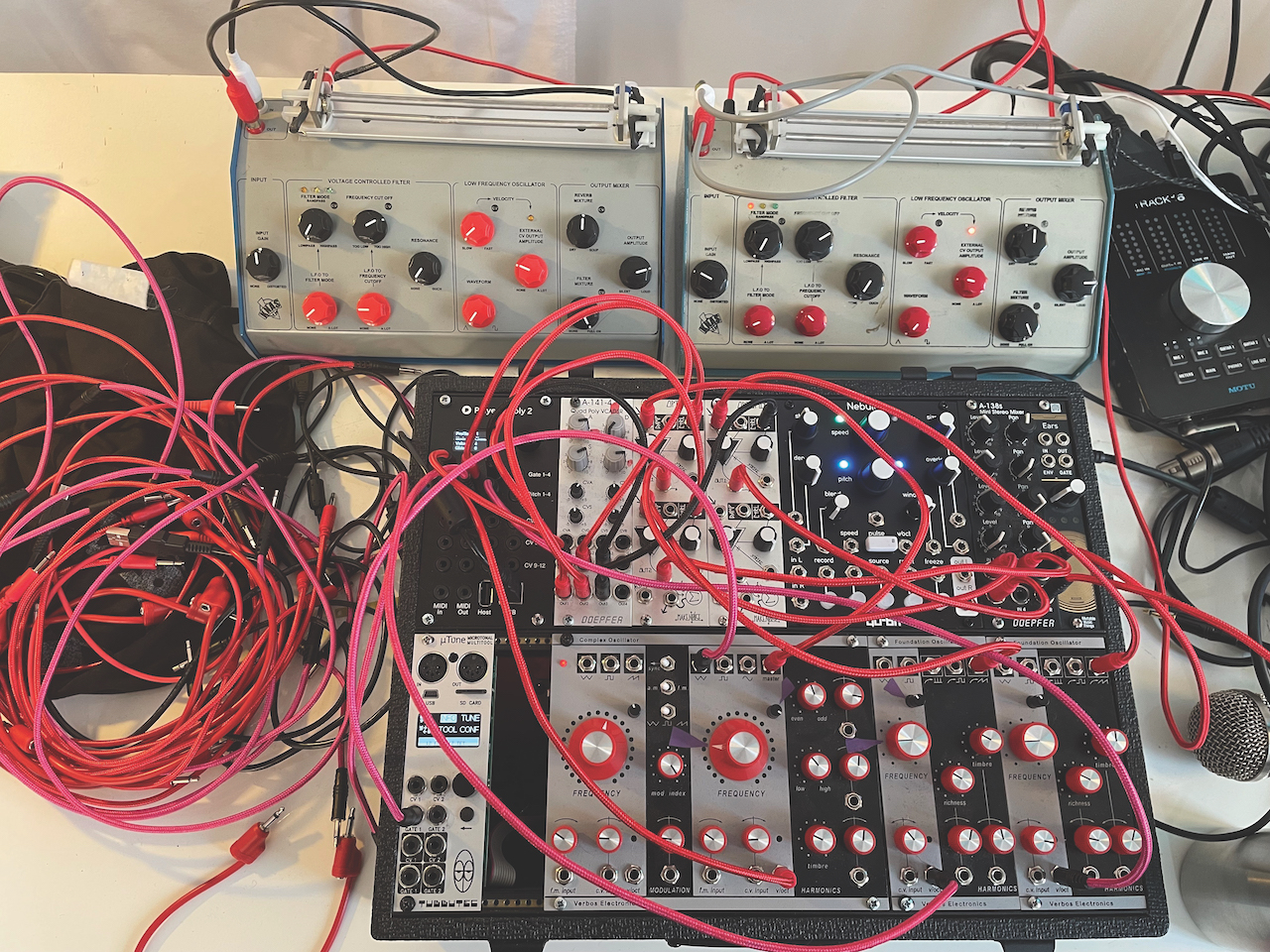

“I made different types of synthesis inspired by the acoustic properties of the prison. Most of it is phase modulation synthesis which I’m a fan of. There’s also an instrument that works almost like a multichannel feedback unit, where you can have several octaves of processing and you can overrun each layer gradually. It goes from a delay-like feedback into a self-oscillating controlled feedback.

"It has organ-like qualities, but that similarity is very much all about overtones and how you use them. Since the vocal tracks were re-recorded from within the building, it works as a re-amp through the prison walls, further enhancing the spectral qualities of the building.”

Maria expands on the benefits of building her own synthesis within the SuperCollider framework. “As you get acquainted with this musical environment, you learn a lot about signal processing and how to incorporate algorithms and chance operations, you develop your own preferences when it comes to thresholds or controlled randomness, much like how you develop your own habits when patching a synthesizer.

"On the server I have my library of synths that I like using – then there’s another paradigm on the client part of SuperCollider which is called ‘patterns’. It’s like an advanced sequencer. You can schedule events and build structures, as a way to sequence your pre-made synths. That’s mainly how I’ve approached it.”

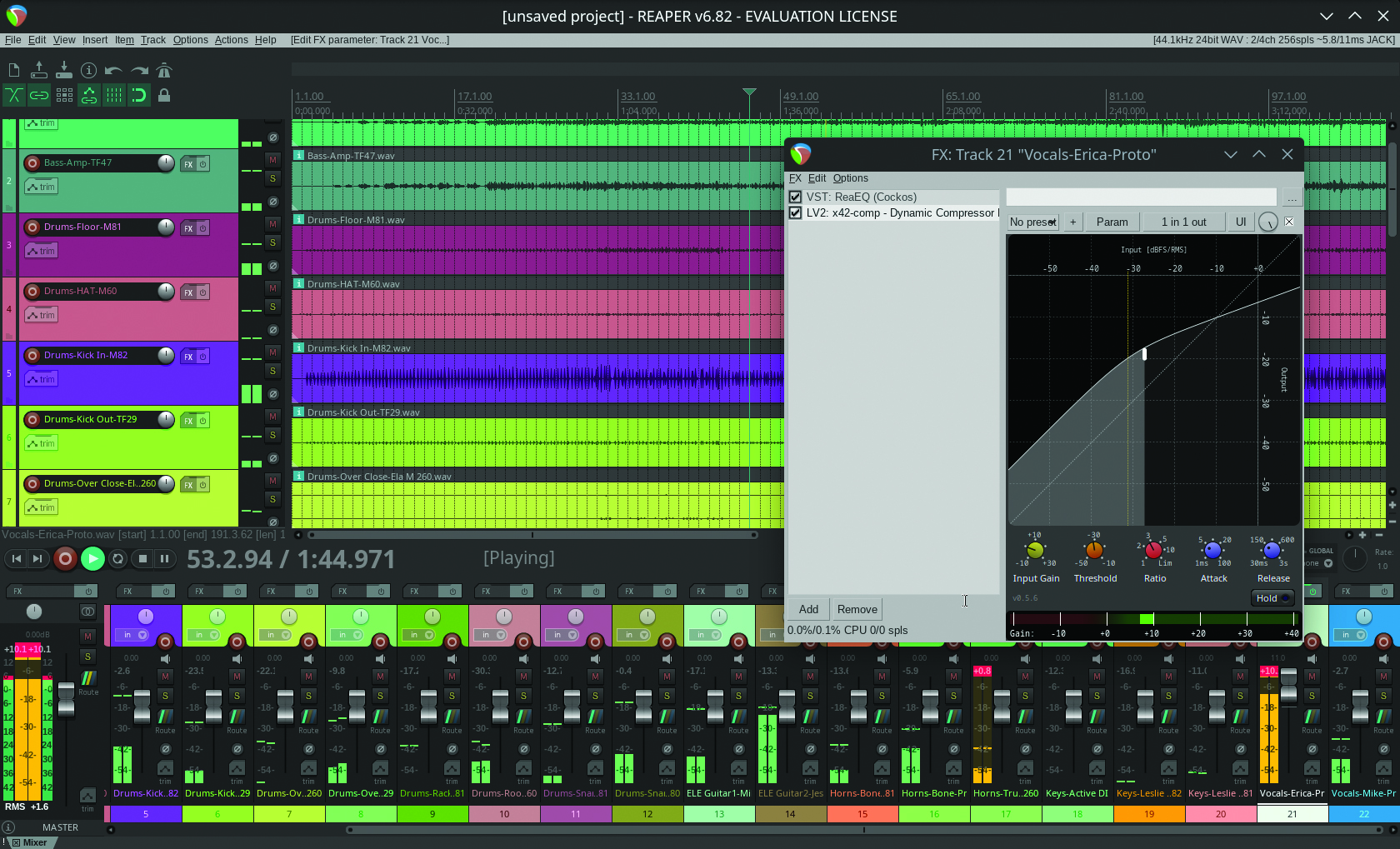

While developing the multi-channel installation required its own space-specific consideration, the mix for the album release posed challenges, too. “It was a nightmare to mix it,” Maria says. “As the installation was multi-floor, voices were coming from above and each side from the different rooms, so there were a lot of phase issues to deal with. The final stereo mix [for the] record was difficult. My first step was to compile the recordings into an adaption for surround sound that was presented at Fylkingen in Stockholm.

Artistic expression can become more intimate when there are more possibilities to adapt the tools of production

“After this, I reworked the material a bit and mixed it to stereo, which of course had to involve a bit of compromise compared to the original spatial idea. In general I’m trying to make stereo adaptions of my multi-channel pieces, as spatial setups are kind of a rare thing to have access to.

“It’s a different dimensionality of course, mixing in stereo,” Maria continues. “As this composition is based on the spatial idea of a panoptic prison, a stereo system is a completely different listening experience. Immersion is a tricky thing. Either you’re non-compromising and seek out the spaces that have these rare multichannel systems, but then you end up presenting your music mainly at institutions and within academic contexts, or you adapt the spatial idea to work in different systems, and I find great value in presenting my music in all kinds of venues.”

We wonder what Maria’s preferred mixing environment is? “I use Logic mainly, or Reaper,” Horn answers. “Panoptikon was recorded in Reaper and then I migrated the files to Logic. I did the final mixing there. It’s a blessing and a curse to get too comfortable with one environment early on. [In Logic] I don’t have to think twice about what I’m doing.”

At the outset of her journey into music production, Maria shunned the larger music production entities, in favour of more DIY approaches. “There were a few years when I only wanted to use open-source programs. I had this idea of big tech companies streamlining the musical choices and compositional possibilities of the users by, for example, offering presets and genre-customised sample banks.

"I’m less restrictive these days, but I still believe that the artistic expression can become more personal and intimate when there’s more possibilities to customise and adapt the tools of production.”

We ask Maria how her journey into the world she now operates in first began. How did she start making music? “I started playing electric bass in punk and folk music bands in my old home town, Härnosand. At the age of 17, I was invited to participate in an evening course of electroacoustic composition. At that point I felt a little bit limited with the electric bass. Having studied the instrument in a jazz-oriented setting, there was a strong focus on virtuosity and being able to reproduce musical standards.

“Learning about electronic music was a bit of a new frontier in this sense. It was like an open field where I did not have to limit my imagination. I guess I got hooked. Since then I’ve been focused on making electronic and electroacoustic music.”

Pattern forming

Maria explains that many of her closest collaborators are friends who operate within Stockholm’s experimental music scene. “My main collaborators are people that I came across at the university, the EMS Electronic Music Studios or surrounding the venue Fylkingen. This venue is something of a national scene for experimental music in Stockholm. Unfortunately they don’t have their space anymore [The Munich Brewery, a space they’ve had since 1986]. When I first moved to Stockholm, that’s where I got in contact with new musical expressions.

We wanted to capture and expand on the interesting intersection between the local neo-classical, noise and electronic music scenes that were specific to the Stockholm scene

“Together with American composer and organist Kali Malone, I co-founded the XKatedral label. We started out DIY-style, dubbing cassettes and setting up release concerts with our friends. We wanted to capture and expand on the interesting intersection between the local neo-classical, noise and electronic music scenes that were specific to the Stockholm scene. A few years in, we involved more people to further expand the scope of the label.”

With an upcoming tour supporting experimental rockers Swans, we wonder if any of the Panoptikon tracks will find their way into Maria’s live sets? “Some of it will be represented but re-adapted into live versions. Instead of the vocal recordings, I will use the vocal lines and sequence them using MIDI to my modular setup. But I’m not strict about playing the record, I will incorporate new ideas as well.”

Maria wants to focus on developing the spectral approach further. “I have some new ideas for site-specific compositions where I want to expand the ideas of using the overtone-spectra as a starting point. I’ve also been composing four-handed organ pieces with my partner Mats. Rooms housing organs usually have interesting histories!”

For more information on Panoptikon and tour dates, head to Maria's official website.

Supercolliding

Originally developed and released in 1996 by James McCartney, SuperCollider is a cross-platform, real-time environment and programming language that is used for audio synthesis and algorithmically driven composition. It lay at the heart of Maria’s approach to making spectrally originated synths and sounds.

It was made open-source in 2002 and, since that time, whole fields of research have been done into developing and expanding the coding language to further manipulate sound in interesting and dynamic ways.

It has three core components: scsynth is at the heart of SuperCollider’s sound synthesis and processing, sclang is the language and sequencing section, that tells scsynth what to do (and when to do it) while the third element scide pertains to the editor and interface, which ultimately links sclang to scsynth.

Since its launch, it has become one of the most widely-used platforms for serious sonic interrogators, artists and acoustic scientific study. More information on what it is and how to use it can be found here.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores the inner-workings of how music is made and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for a range of titles including NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.