“Hildur’s instrument kind of occupies the typical guitar frequencies, and it feeds back. She often calls it a Jimi Hendrix cello”: Osmium - a new collective featuring Hildur Guðnadóttir - talk self-built instruments and exploring wild frontiers of sound

The Chernobyl and Joker composer’s new project leans on self-built instruments - and the brutal vocal textures of Rully Shabara

One of the luminaries of modern soundtracking, Hildur Guðnadóttir’s distinctive scores are often the standout element of her varied projects. From the eerie, unnerving tension of Joker to the unyielding constriction of Chernobyl, Hildur’s cello-centric compositional approach has garnered accolades from all quarters. Among which, an Oscar and a couple of Grammys.

But Hildur’s latest venture finds the storied Icelandic composer join three similarly adventurous artists, investigating the outer fringes of sound - and relying on some extraordinary self-built instruments.

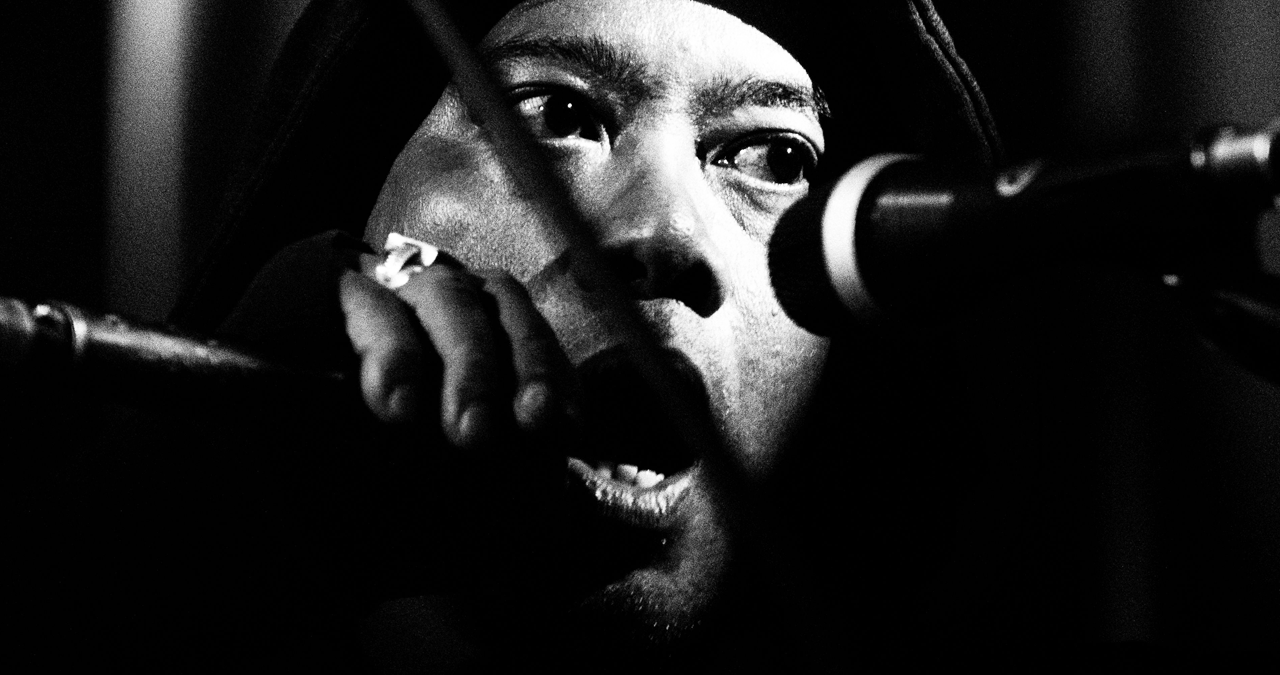

The four-piece, Berlin-based Osmium consists of Hildur, her partner and frequent collaborator Sam Slater, and Emptyset's James Ginzburg (who also runs label Subtext) - all of whom use a plethora of extraordinary contraptions to create a wholly unique sonic universe. On vocals; Rully Shabara - an improvisational vocaliser who uses a range of techniques to contort his voice into unique - often abrasive, often captivating - forms.

Those self-built instruments are intriguing. Hildur’s halldorophone - designed by Halldór Úlfarsson - evolves her cello into an electroacoustic domain, and enables the user to generate unstable, unpredictable feedback loops.

Meanwhile, Slater concocts rhythms using a self-oscillating drum that was co-designed with KOMA Elektronik. Bringing up the low end comes James with a bass device that generates sustained, drone-like resonances. An echo of the classic traditions of folk, albeit with a modern twist.

Alongside these contraptions, there’s a customised system of robotic solenoid hammers which - when fed MIDI instructions - lock into percussive rhythms that help to cement Osmium’s arrangements. All the while, Shabara’s voice interacts and interweaves with the resulting sound - an aural depiction of the tension between human and machine.

With the fruits of Osmium’s creative labours now collected on a self-titled album (which you can stream and purchase here), we sat down with the members of the band (aside from Hildur, unfortunately) to find out more about these self-built instruments and the concepts underpinning this challenging project.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

MusicRadar: Firstly, we really enjoyed the record - it’s both visceral and aggressive yet still seems to evoke some complex, human themes…

James Ginzburg: I guess it's a weird record in general, because, in a sense, the process we took to approach it sort of dictated the results. But I guess at the same time, all of us have been involved in musical projects that might be described as ‘aggressive’. But, I don't feel like it's aggressive for aggression sake.

All of us have come from an approach that involves electro-acoustic music. There’s also something quite retro about the technology that we've used.

There are computers that still factor into what we're doing. For example, there's a computer putting out the MIDI to control the solenoids which strike the strings - but even then, we're still talking about 40 year-old technology.

The way that we've all found, I think, in our individual practices, as much as in this project, is that there's a certain kind of poetic license when communicating something about modernity. Sometimes it's not actually the kind of horizon of technology’s possibility that can evoke something that feels extremely visceral.

Now, if you think about the kind of sounds out there in the world that people are having to endure - and the kind of violence around them. These things are not necessarily the sounds of computers. Think about the sound of a drone, for example. It's a kind of propeller moving through the air. I think a discourse inevitably comes out - which is built around exploring the relationship between humans and technology. But in a sense, I think that's as much a conversation that kind of connects back to the 1960s and cybernetics as it is to something that connects to the current iteration of our struggle with machines.

MR: So what motivated you to found Osmium, and how tricky was it to land on this unique approach to music-making?

Sam Slater: Well, we knew of Rully and had seen him play live. We were huge fans of his work. Yet the Osmium conversation sort of initially started with James, Hildur and I, who were based in Berlin.

We’d all been been exploring some instrument building, and we were all kind of excited by by a sort of ‘jankiness’ that came from that.

We were kind of thrilled about having these instruments that were harder to control - you're kind of forced into a dialog with them because it doesn't always do the thing that you expect or want.

We had the idea to take these three instruments and put them on stage.

Hildur’s instrument (the halldorophone) kind of occupies the typical guitar frequencies, and it feeds back. She often calls it a Jimi Hendrix cello. And James has got something which is ostensibly based on a bass guitar.

Though, you know, you can frame all of these instruments [in a band context], but you can look at them through different lenses. If you come from more of a folk background, you're going to say [of James’ instrument] ‘oh, it's based on a on a monochord’.

I work with a drum. But it feeds back - so it's also out of control!

With this set-up, we were like, ‘ah, okay, we should get a vocalist’, and we decided to make it into a band. Then the conversation was like - well who could handle this?

There's pretty much only Rully, I would say, in the world who could do it.

Our next conversation was how to take these instruments and create some sort of structure.

Feedback is, by its very nature, uncontrolled. Having robotics set against that - or solenoids set against that - creates a nice dialog there. There’s a beautiful balance between the sort of rhythmic accuracy of the solenoids and the chaos of the feedback.

MR: So Rully, how did you approach this material from a vocal perspective?

Rully Shabara: It wasn’t easy in the beginning to work out how I should ‘treat’ myself in the project. How would I do it differently [to how I normally sing] and what kind of angle should I do it with?

Should I do more rhythmical? Should I do more textural? Should I even be doing melodies - I just didn't know at the beginning.

It's a very strange project, with all these mechanical things being very precise - and very loud! Even after the first few shows, I was still trying to [work it out], but after the recording of this album, I think it really helped. Recording at James’ studio gave me a lot of insight into how to do this.

I'm more comfortable now, but it’s still challenging at the same time. How do you put yourself out as a vocalist and use only your voice to compete with these three heavy machines that are not only loud, but ultra-precise, as well as the feedback and noisy sounds.

MR: Well, let's talk about these instruments in more detail shall we. So Hildur, as you say, is on the halldorophone, James is behind the resonating bass instrument and Sam helms the self-oscillating drum - can you talk us through the specifics of these instruments?

James: Well, what I play is sort of a plank of wood that has a set of six string bass strings on it.

You can tune each string to one note, and that's basically all you've got. Then there's various ways of interacting with it, whether it's using your fingers, using a bow, or using a mallet.

With both Hildur and Sam's instruments, there are sort of rhythms being imprinted into them via these solenoid hammers.

This then forms a very broad skeletal structure that creates the basis of each track. With tempo set, the music comes from sort of reacting to and playing around with those structures that are imprinted into our instruments.

I think, you know, because of the nature of my instrument there is a kind of inherent limitation. My instrument - for the entire duration of the album - is tuned to just two octaves. You basically have one note, and any sort of deviation from that is coming from either Hildur or Rully or from Sam's drum feedback.

But the foundation of each piece is basically this bass drone. It kind of connects it to quite a few different musical traditions, just by the virtue of how it's inherently locked into that sort of form.

I designed the instrument on the back of a napkin, so when it was made, it had some unexpected properties. An example of which is the sort of tamboura-like sound with a set of harmonics on the top. It creates a really rich and complex sound that was kind of emergent rather than something that was calculated.

With these instruments, whether it's Hildur’s halldorophone, or Sam's feedback drum, there's all this potential for kind of emergent complexity to rise out of each instrument, which creates an interesting landscape for Rully to try to interact with.

It creates a sort of interesting alchemy, which then creates the kind of macroscopic emergent property, which is the music that you hear.

MR: I’m guessing that it’s those solenoid hammers that are what’s behind the mechanical, almost oppressive industrial sounds that appear throughout the record - how did you construct those, and why did you decide to deploy them in this way?

Sam: Basically we worked with an electronics company in Berlin. It’s quite simple. It's 3D printed frames with the solenoids with hammers connected to them. There's a MIDI instruction that's coming out of a computer, and each instrument is being struck at the same time.

Oppressive is actually a good word, and I guess you can imagine it's quite divisive as a performance. Particularly when that oppression is extremely loud!

I feel like the sort of like the human [element] comes from our choice in how we respond to these machine elements.

James: We struggled with the term ‘robotics’, just because, one: it sounds a bit silly. And two: they're not robots.

It's a very simple system. But I think, like, ‘mechanical sequencer’ is better, as that’s what we’re doing. We're sequencing something mechanically. And I think that you know you've got, as I said before, you have feedback and you have human interaction, and these create complex things to listen to.

It’s really strange to just let the instruments run and know that, if I don't play anything, these mechanical sequences will just do their thing. We then wait for the right moment to join back in and that can be a really thrilling interaction.

MR: How tricky was the recording process for the album?

James: The recording process took four days - two of which were spent trying to make Hildur’s instrument work!

We didn't record anything until the final day, when we had something that vaguely approximated a functional setup.

I guess that's the kind of challenge with this sort of kind of project where everything's self-built, it's handmade, it's not mass produced.

This link breaks. Then you're potentially dealing with a one-of-a-kind object that you have to work out how to improvise in order to make it work.

But I think the fact that you know, you know Hildur particularly, has had such a huge volume of experience as someone who has worked with very forward-looking improvisational groups - she has this kind of aura of confidence, even when everything's falling apart.

Something will happen like some [amazing] sound will happen. And, it might not be what you thought would happen.

And some of the stories she tells, of her being on stage by herself, and everything completely breaking down, and her still being able to pull the performance out of it, I think that's probably [down to] nerves of steel, really.

MR: Once you had the recordings in the can, how long did the mix take?

Sam: The mix was significantly longer than any other.

I know that's how James and Hildur work - you capture something, and then you basically use what you captured to kind of form the final product.

So there was a whole phase of production which was basically just editing things down, because all the instruments were tracked simultaneously. Then we overdubbed the vocals.

So really, we were kind of massaging all the parts for a while, then the in-depth mixing sessions took us maybe a year after we recorded.

There were many reasons for that. One was the suite was quite complicated, two was just that we were all doing so many other things.

It’s such intense and abrasive music, figuring out how to present it in a way that made for an enjoyable, absorbing listening experience - rather than a kind of caustic and exhausting one - was a very delicate balance.

I can remember showing Hildur when we kind of got to a point where James had completed a lot of the editing. Hildur was the person nominated to listen as little as possible. So she had precious ears - and she was ever so slightly apprehensive about listening to the final thing.

She was really unsure if this was going to work as a record, whilst being fully confident with it as a live show.

When she listened she was just like, ‘wow, that's a tight record!’. That was a really nice feeling.

MR: What are your favourite moments on the record?

Rully: For me, it’s the last track - it’s the one we play last for a reason.

It’s not a safe bet - but then I'm not sure any of this is a safe bet - but you know what I mean, it’s like, intense - but it’s a solid ending.

We all know what direction it's going in. So live, it's one of the easiest to get right. On the record, I think it was probably the exact opposite,

MR: So with the debut album now released, do you intend to continue as Osmium and do you intend to keep making music in this vein - or are you keen to explore new sonic ground?

Sam: I think for us, the next step is really to consider developing new or elaborate instruments - and then to see where that takes us.

Probably in all of our individual practice, a primary thing is that if you don't have an idea, you don't make a record. There's no point.

Osmium has been a very, very fun project to do, and it's a very fun group of people to spend time with. I think we'd all love the idea of figuring out ways of doing that more, but I guess we all have extremely high standards.

We’re constantly asking ourselves, ‘is this is this good enough? Is this cool enough?’

MR: Do you wish that more experimentalism - such as what you’re doing - had more of a mainstream following, or had exponents who were also hugely popular?

James: Well, there's an ear out there for every sound, I guess. But yeah, it's a tricky thing. If you want to pitch something within the Spotify ecosystem, you have to define what ‘genre’ it is or what your music’s references are.

Then you have these people creating playlists for them. But where do you put Osmium?

So, in a sense, you know, the structures that deliver music to people actually have the opposite effect. They seek to quantize possibilities into easily digestible and presentable forms. It was always that, but now it’s algorithmic.

It’s not massively inspiring for me to reverse engineer the kind of corporate mechanisms of algorithmic music distribution. So I think the most important thing is that we do something that's inspiring for us. But it is very possible that the structures of the world are such that it's impossible to interface that with anybody else,

But I think it's completely okay to make something that you enjoy. To make something that just five people really get then that's fine.

You can stream and purchase Osmium's debut album from their Bandcamp page here.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.