“This business can really get tough sometimes, and you have to dig deep inside you. Paul looked for something else to lean on, and the thing he leaned on had no future in it”: How a gifted guitarist’s descent led to the rise of ’70s supergroup Bad Company

The band were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame on 8 November

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Bad Company’s debut album topped the US chart in September 1974, its success seemed preordained. In this band there was so much talent – and behind them, so much muscle – that failure was never an option.

Since the late ’60s, established stars had come together in rock supergroups such as Cream, Blind Faith and Derek And The Dominos – all featuring Eric Clapton – and in Humble Pie, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

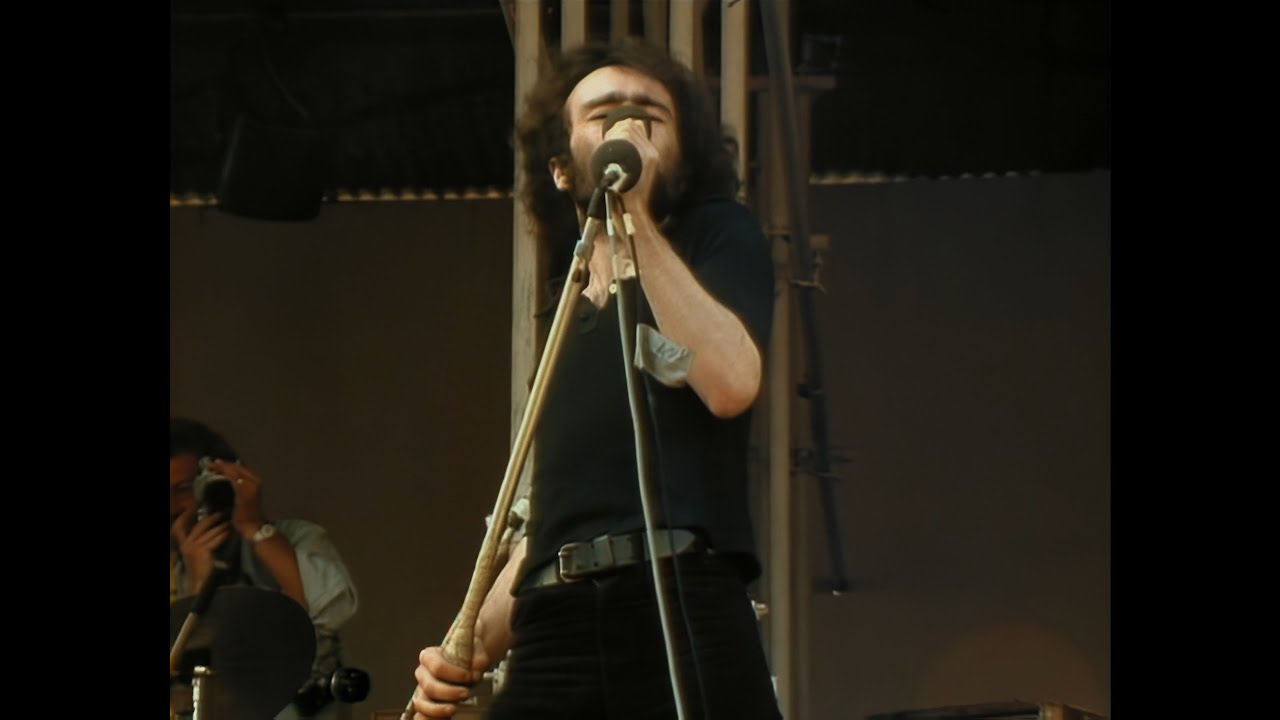

So it was with Bad Company. Singer Paul Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke had starred in Free, guitarist Mick Ralphs in Mott The Hoople, bassist Boz Burrell in King Crimson.

In addition, they had Peter Grant as their manager, the man who had steered Led Zeppelin to mega-stardom. And the first Bad Co. album was also the flagship release for Zeppelin’s vanity label Swan Song.

For Rodgers and Kirke it was a new beginning after the messy demise of Free in 1973 – hastened by guitarist Paul Kossoff’s descent into heroin addiction.

As Rodgers said, many years after Kossoff’s drug-related death in 1976: “This business can really get tough sometimes, and you have to dig deep inside you. Paul looked for something else to lean on, and the thing he leaned on had no future in it.”

What Rodgers found in Mick Ralphs was a great guitar player without Kossoff’s self-destructive streak. Between them, Rodgers and Ralphs wrote all of the songs for the Bad Company album. And in its making, there was no messing about.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In November 1973, when a Zeppelin recording session at Headley Grange in Hampshire was delayed, Peter Grant put Bad Company in there to record a couple of tracks. Instead, they were so tight that they had the whole album done by the time Zeppelin showed up.

Inevitably, there were echoes of Free in Bad Company’s swinging, soulful hard rock – in the way Kirke held down the groove, and in Rodgers’ unmistakable, richly expressive voice. Ralphs also dug into his past by resurrecting his song Ready For Love from Mott The Hoople’s landmark 1972 album All The Young Dudes.

But at the heart of Bad Co. – in the dynamic between Rodgers and Ralphs – was something fresh and distinct, powerfully illustrated in the tough-guy strut in Can’t Get Enough, in the simple beauty of the acoustic number Seagull, and most of all in the signature song Bad Company, a moody outlaw blues.

The band had a long run at the top, with more classic albums – notably 1975’s Straight Shooter and 1976’s Run With The Pack – until diminishing returns led to their break-up in 1982.

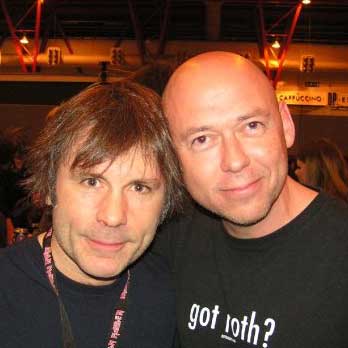

Over the years, Paul Rodgers ended up in more supergroups than Clapton did: in The Firm, with Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, in The Law, with former Small Faces and The Who drummer Kenney Jones, and in one of the more bizarre alliances in rock history, Queen + Paul Rodgers.

But never again did he find what he had in Bad Company. For this great singer, who had lost so much in Free, it was the right band at the right time.

Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.