“His death was no different from his life - a work of art”: A decade on, we remember how David Bowie rose above his impending end to create his most poignant work

Bowie’s heartbreaking Lazarus was a rumination on the imminent end of a life lived to the full - and a lesson in how to channel the bleakest situation into enduring music

This January marks a full decade since the world lost one of its most hailed musical heroes. The death of David Bowie, on January 10th 2016, was a blow that sent generations of fans spiralling into a very keenly-felt grief. This writer being one of them.

I, like many other Bowie-nerds, had giddily pre-ordered his upcoming twenty-sixth studio album, Blackstar, months prior. I received it on the Friday (8th) before that fateful weekend on which he passed.

It's tricky to remember my exact feelings on the album during that odd interstitial period before its defining context became clear, but I do recall listening to Blackstar multiple times during that rainy weekend.

I was captivated by the jazzier direction of musical travel, but I also definitely felt that there was a deeper theme that I was not quite latching onto - an elusive subtext that seemed to permeate those seven tracks that was hard to put my finger on.

A few days later, and in the wake of the news of Bowie’s death, the record’s underlying meaning suddenly revealed itself.

That spectral presence hanging over every minute of Blackstar was no simple stylistic choice. It was the sound of the very weight of David reckoning with his last days on Earth, channelled into every note and word of the album.

How could we not have known?

It turned out that Blackstar was Bowie’s artistic response to the reality that his time was coming to its end. And where do you begin to take stock of a life as lived as his?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Diagnosed with liver cancer 18 months before his eventual death, Bowie had been undergoing energy-sapping chemotherapy and mentally coming to terms with the strong possibility that his time was short. He opted to keep his condition quiet, sharing it only with his closest collaborators.

Making another studio album, then, would be a tall order for most people facing such a debilitating treatment plan. But for David Bowie, an artist long fascinated with mortality, the knowledge that his life would likely soon end seemed to only stoke his creative fire.

Though death had been a long-recurring theme in Bowie’s body of work, on Blackstar it would be an omnipresent character.

This was to be no comfortable retread of previously explored musical ground either. Bowie and his long established producer Tony Visconti enlisted the Donny McCaslin jazz quartet to expand the often vibrant and often unnerving musical language of an adventurous and at times audacious record.

“When David saw us he heard how electric and aggressive we were - more than he anticipated - which really sold us to him,” said the group’s bassist Tim Lefebvre in an interview with Mojo.

Inspired by the group’s loose, reactive and instinctual performance style, Bowie directed the McCaslin band to respond without inhibition to his work-in-progress songs.

Amid this clutch of cuts were a few that Bowie had penned for his off-Broadway musical, Lazarus - another project undertook during this intensely creative timeframe. Chief amongst them was its title track. The song that would become most synonymous with David’s death.

“Every song was really strong and the demos were really strong,” recalled McCaslin in an interview with NPR. “In fact, when we ended up recording, we pretty much were true to the demo forms he had sent. So it was tremendous."

With much of the music tracked at New York’s Magic Shop between January and May 2015, Blackstar’s seven songs spanned the driving, art rock snarl of ’Tis a Pity She Was a Whore, the resolute (and Berlin trilogy-quoting) I Can’t Give Everything Away, the intense jazz-prog opus that was the title track (which we discuss in greater detail here) and at the centre of it all, that aforementioned title track of Bowie’s musical - and the record’s most pointed meditation on death - Lazarus.

The song’s liminal arrangement was presaged by a meandering one-note riff that resembled a gradual trickle of liquid.

Its up-and-down momentum snaked around the intro, establishing the boundaries of an arrangement that suggested inertia, isolation and meditation.

“The intro didn’t exist on his demo,” said drummer Mark Mark Guiliana in an interview with Modern Drummer. “But after the first take we kept playing and Tim [Lefebvre - the group's bassist] started playing this beautiful line with the pick, which David liked and thought it would make for a nice intro. He was very much in the moment crafting the music.”

The prevailing purgatorial mood was fully defined once the further instrumentation kicked in, hinging mainly on a gradual lurch back and forth between A minor and F major. A morose, descending sax motif levitated above this foundation, while a pulsing central drum beat kept a rigid pace.

Anguished howls of despairing electric guitar scratched violently across the arrangement, and McCaslin’s jazz quartet gradually ramped up their intensity with each successive verse.

Even leaving aside the lyric, Lazarus’ music itself was imbued with constriction, obvious pain and - as implied by its perpetual chord cycle - a crushing feeling of inevitability.

But it was the song’s lyric, and Bowie’s impassioned vocal performance, (recorded at Human Worldwide Studios in New York City a few months after the backing track was completed) that would be the most touching component.

“He’s in that song, in that feeling, in that moment,” remembered Bowie’s long-time producer Tony Visconti in the documentary film David Bowie: The Last Five Years. “He would stand in front of the mic and for the four or five minutes he was singing, he would pour his heart out.” Visconti then demonstrated that the final vocal take had also captured Bowie’s intense breathing.

“It wasn’t that he was out of breath, it was that he was hyperventilating in a way,” Visconti continued. “Like, he was getting his energy up to deliver this song. I could see him through the window he was really feeling it.”

The titular allusion to the Biblical figure of Lazarus, whom Jesus Christ rose from the dead, is never referenced directly in the song, instead its lyric is seemingly a communiqué from an abstract, post-death space.

With references to being ‘in heaven’ and of looking down on the world from a great height (‘I’m so high it makes my brain whirl, dropped my cell phone down below’), it felt as if Bowie is framing the song as if he had already ascended. Here he was, inhabiting his own immortal shade, viewing events of both past, present and future omnisciently.

Look up here, I'm in heaven

I've got scars that can't be seen

I've got drama, can't be stolen

Everybody knows me now

It’s tempting to read that last line as Bowie anticipating the impact his death would have on his legions of fans, and the sudden re-appreciation that would take place across popular culture in the wake of the news coverage.

For key Bowie author Nicholas Pegg, these lines were a culmination of yet another ongoing theme in Bowie’s work - the unpicking of the notion of celebrity.

“This was merely the latest in a long line of pointed quips about the pitiless flip-side of celebrity,” Pegg wrote in his analysis of the song in his weighty (and compulsory!) Bowie tome, The Complete David Bowie. “From Space Oddity with its ‘papers’ who wanted to know whose shirts Major Tom wore, to the bullet in the brain that ‘makes all the papers’ in It’s No Game. On that dark day in January 2016, everybody knew David Bowie.”

The song’s bridge shifted gear, and leapt momentarily into a brighter-sounding (but still somewhat uneasy) C major-led section that housed a frank reminiscence of a prideful, lust-driven youth, now long in past.

By the time I got to New York

I was living like a king

There I used up all my money

I was looking for your ass

The song’s final verse hit particularly poignantly after Bowie’s departure. Its lyrics delivered with palpable emotion as McCaslin and co frenetically pushed into a full jazz-freakout.

While the lines pertaining to being free and soaring like a bluebird were undeniably affecting, it was the ‘ain’t that just like me?’ line that landed most heavily with this writer.

It was almost like a hand of reassurance - Bowie's nod and a wink to his fans from the afterlife.

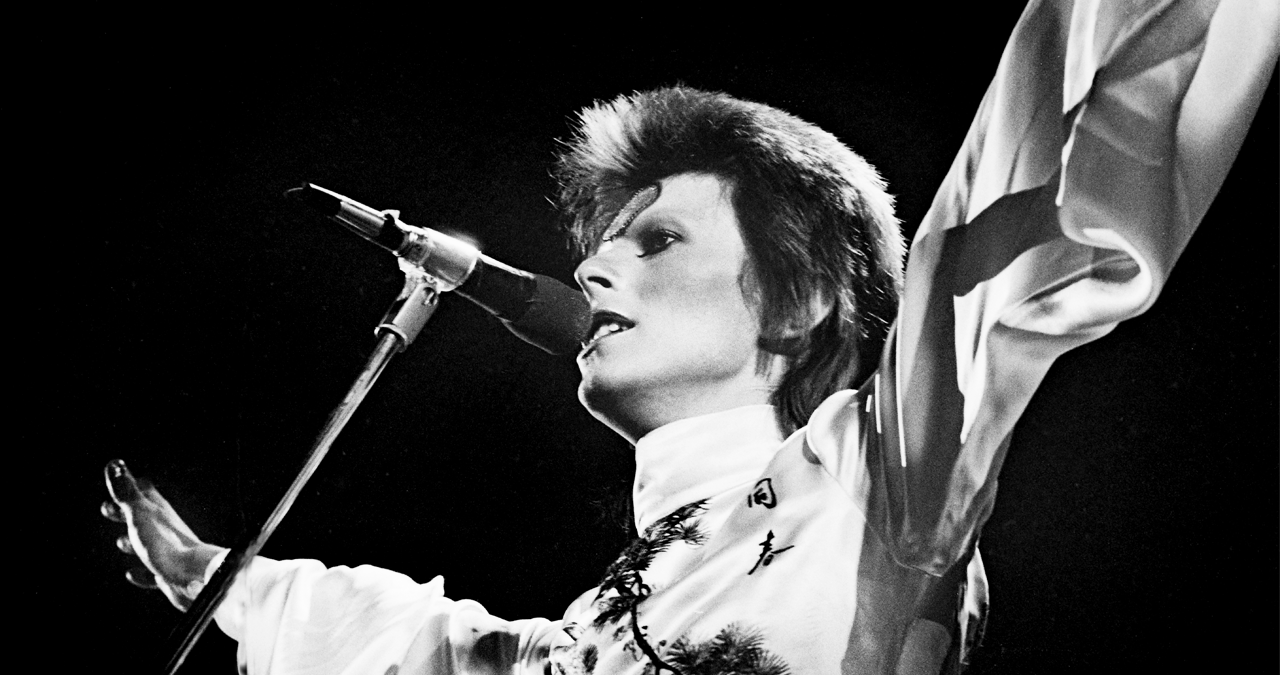

To me, it read as self-acknowledgement that the orchestration of Bowie's final bow was as knowingly and characteristically shrewd as his 'killing' of Ziggy Stardust at London's Hammersmith Odeon all those years ago.

As with that seminal moment in music history, Bowie was still the puppet-master, cannily engineering great art. This time, though, it was great art framing his actual death.

This way or no way, you know I'll be free

Just like that bluebird now, ain't that just like me?

Oh, I'll be free, just like that bluebird

Oh, I'll be free, ain't that just like me?

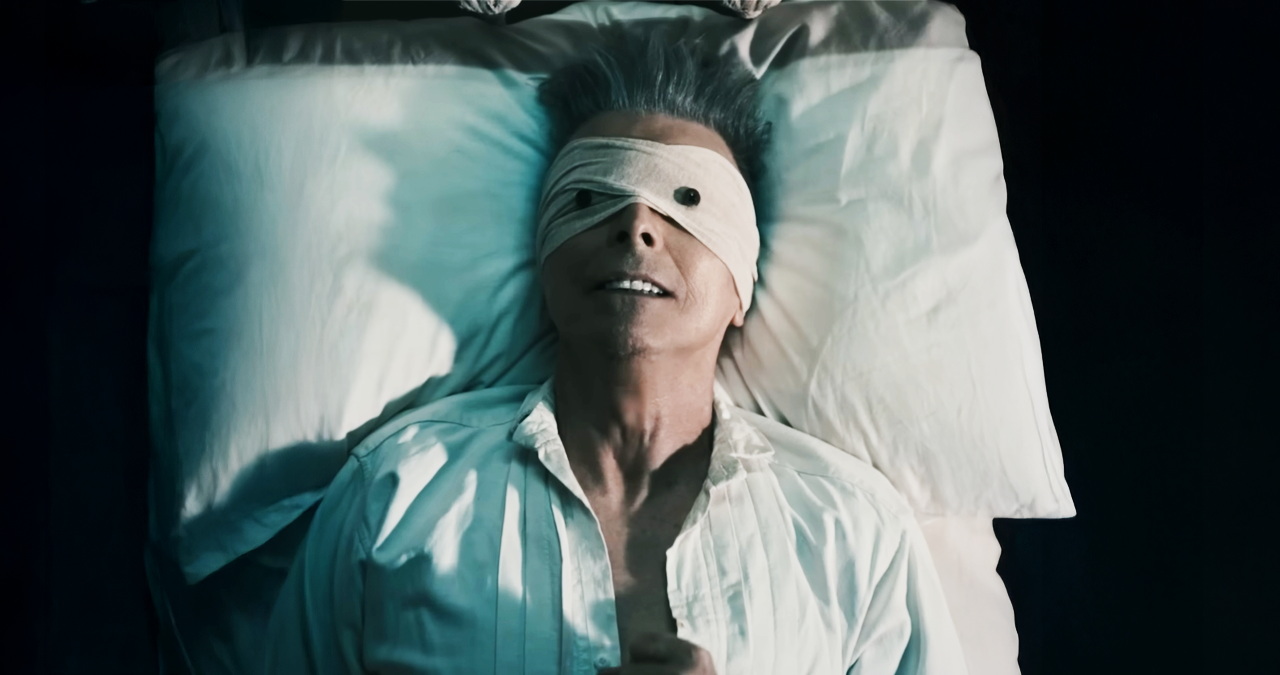

Lazarus would become an enduring lament on mortality and legacy, but it was the imagery of its tear-inducing video, directed by Johan Renck, that would be instantly summoned to the mind's eye when hearing the song.

Many found it just too painful to watch.

Previously collaborating with Bowie on the exemplary Blackstar video, Renck directed the Lazarus shoot that was conducted in November 2015, just two months prior to Bowie’s death.

Although conceived before his treatment was drawn to a close, the Lazarus video project would ultimately be Bowie’s final music video, and its creators were very cognisant of the fact that this project would be Bowie’s final work as a musical artist.

“Over Skype he said ‘I feel I have to tell you this. I’m very ill and I may not make it’,” Renck recalled in an interview with The Guardian, remembering his conversation with David prior to filming the Blackstar video.

“I had been in this playful mood, pitching ideas back and forth with him like giddy 12-year-olds and I was absolutely shocked. He said: ‘I don’t even know if by the time we shoot this video you will have to have a replacement for me to perform in it’,”

The Lazarus video depicted a hospital bed-bound Bowie, alone within a drab, tiled room. Clad in the same ‘button-eyes’ eyemask that had previously been worn in the Blackstar video. The mask has been read as an allusion to the mythological notion of pennies being placed on the eyes of the dead, in order to pay for passage to the afterlife.

As the video progressed, the bedridden Bowie delivered the song’s lyrics, clutching the bed-sheets fearfully before levitating upwards - an apparent visual signifier of a heavenward, saint-like ascent.

Meanwhile, another figure crept around the room unnaturally, appearing underneath the bed, within an ominous, looming wardrobe and at the door with outstretched arms.

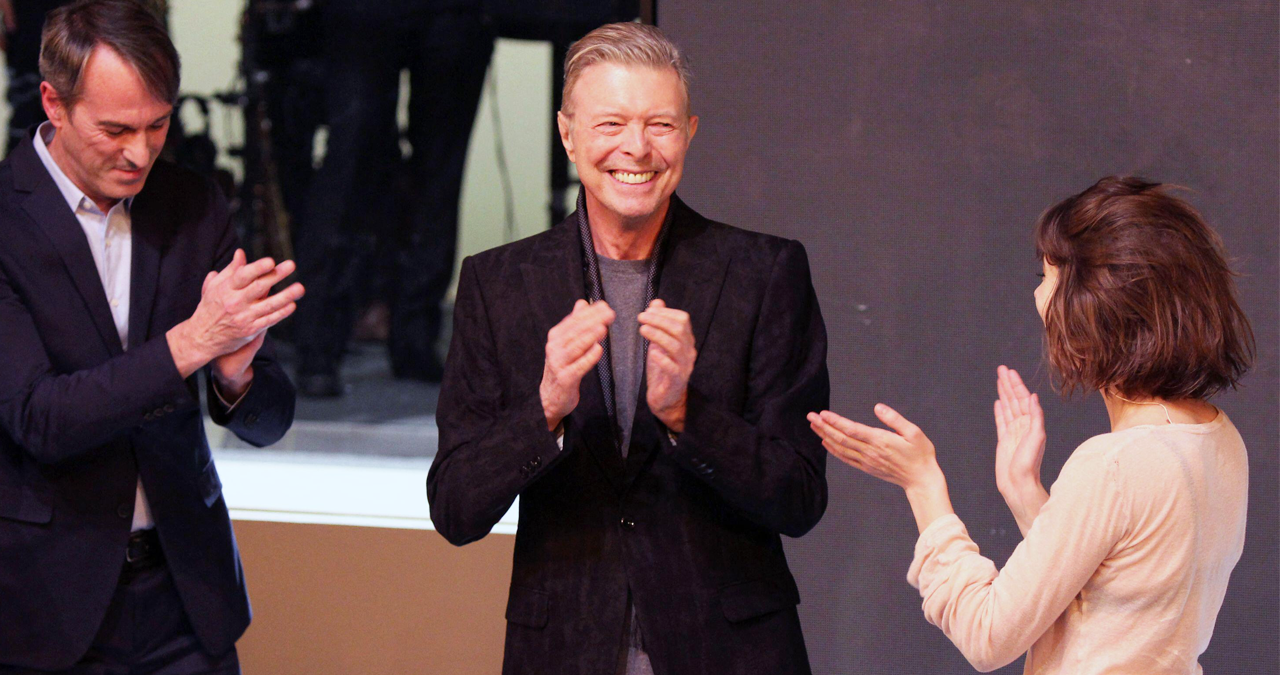

For the bridge part and during the finale, Renck cut to a very different Bowie, who (as any Bowie-geek will tell you) was wearing the same striped bodysuit previously worn during a notable photoshoot from the 1976 Thin White Duke era.

David's mannerisms and performance style were wholly different to the Bowie in the bed, this incarnation posed and hip-swung in a theatrical and stylized manner. The last strut of glam rock's most enduring titan.

The final verse of the song also intercut back to the bedded button eyes-Bowie, now lifting his hands evangelically and joyfully smiling in a seeming embrace of death.

Johan cut back to the energy-fuelled Bowie, now sat at an old schooldesk, making big, mime artist-like movements that implied being struck by a creative idea, and furiously jotting them down in his notebook. An acknowledgment of the delirious rush of a man who still had so much to give, working against the clock.

As the song concluded its crescendo, this second Bowie retreated backwards into the coffin-like wardrobe, his steely eyes fixed on the camera.

While the visual concepts were conceived before Renck was made aware that Bowie’s treatment was coming to an end, David himself was processing his imminent death throughout the shoot.

“I found out [that] the week we were shooting, it was when he was told it was over, they were ending treatments and that his illness had won,” Johan said in The Guardian. “I just thought of it as the Biblical tale of Lazarus rising from the bed. In hindsight, he obviously saw it as the tale of a person in his last nights.”

10 years on, and the pain of Lazarus still cuts deep, but it has also become the cornerstone of Bowie’s final record.

David's last act was both a reckoning with his mortality, and an artistic high that will forever leave us wanting more from a creator who gave the world so much.

That period after Bowie’s death was, without hyperbole, a genuinely upsetting time. To suddenly be in a world without David Bowie was a reality that I, and I’m sure many other fans, didn’t quite realise would be as unbearable as it was. But Blackstar was a faith-confirming feat of ascendancy over death - a wily capstone that kept us guessing until the last possible minute.

It was so Bowie.

“I knew for a year this was the way it would be. I wasn’t, however, prepared for it,” said Tony Visconti on Facebook when Bowie’s death was announced.

“He always did what he wanted to do. And he wanted to do it his way and he wanted to do it the best way. His death was no different from his life - a work of art. He made Blackstar for us, his parting gift.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![David Bowie - Lazarus (Official Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/y-JqH1M4Ya8/maxresdefault.jpg)