“He had this toy, but one day he came to work and told us that the toy had become a man”: How an advanced drum machine saved a difficult Steely Dan album

The innovative machine also received its own platinum record for its painstaking drum replacement

During our recent Drums Week here at MusicRadar we were reminded of the fits and starts history of the drum machine. One particularly fascinating and pioneering device we felt was worth exploring a little more was invented during the making of Steely Dan’s 1980 seventh studio album, Gaucho.

Assembled out of necessity, this early drum sampler was hand-built and programmed by the group's executive engineer and technology-obsessed inventor Roger Nichols.

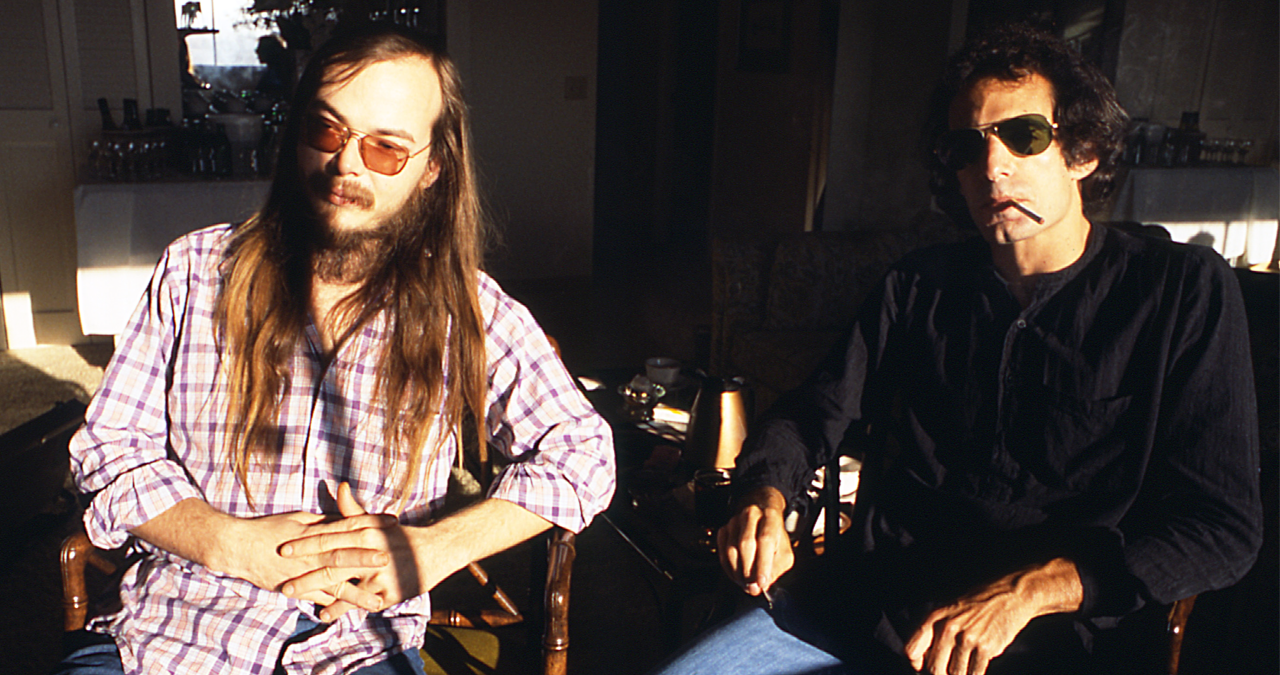

Essentially the musical vehicle of two men, Steely Dan’s co-head honchos Donald Fagen and Walter Becker were well established as studio perfectionists. No facet of a track was left un-scrutinised. But, on this occasion the difficulty in achieving what the polymath musician pair wanted for their song Hey Nineteen, using session drummers, was proving endlessly frustrating.

Recording for the follow-up to their best-selling album Aja began in 1978 but would take a further two years to come to fruition. The first hurdle was establishing a solid drum track - the basic foundation for the pair’s musical exploits.

The standard route was recording with a session drummer and rotating the surrounding instrumentalists (in the hopes that the drummer would adapt to their myriad playing styles in interesting ways).

This is best illustrated by the fact that although more than forty musicians were brought in during the recording sessions for Gaucho, only seventeen appeared on the final record. While some takes were better than others, the core drum parts were just not quite right.

What Fagen and Becker sought was the then-impossible ability to move constituent drum elements around after the fact, as we can comfortably do now within our DAWs.

Producer Gary Katz recalled in a NAMM tribute to Nichols that, after slaving over hours (and room-spanning meters) of drum recordings on tape, Donald turned around to Roger and bluntly asked; “Can’t you make a f*****g machine that would be perfect?”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Nichols had already been thinking along similar lines. A mainstay of the Steely Dan production team and a keen technologist, Roger had speculated about devising such a system, cutting down the time taken in the studio whilst also developing his coding abilities to push further the abilities of computers in helping to sequence music to order.

Requesting a not inconsiderable investment of $150,000 and six weeks time to build his solution, Nichols set to work. Using a CompuPro S100 computer as the foundation for a new, beat-focussed machine.

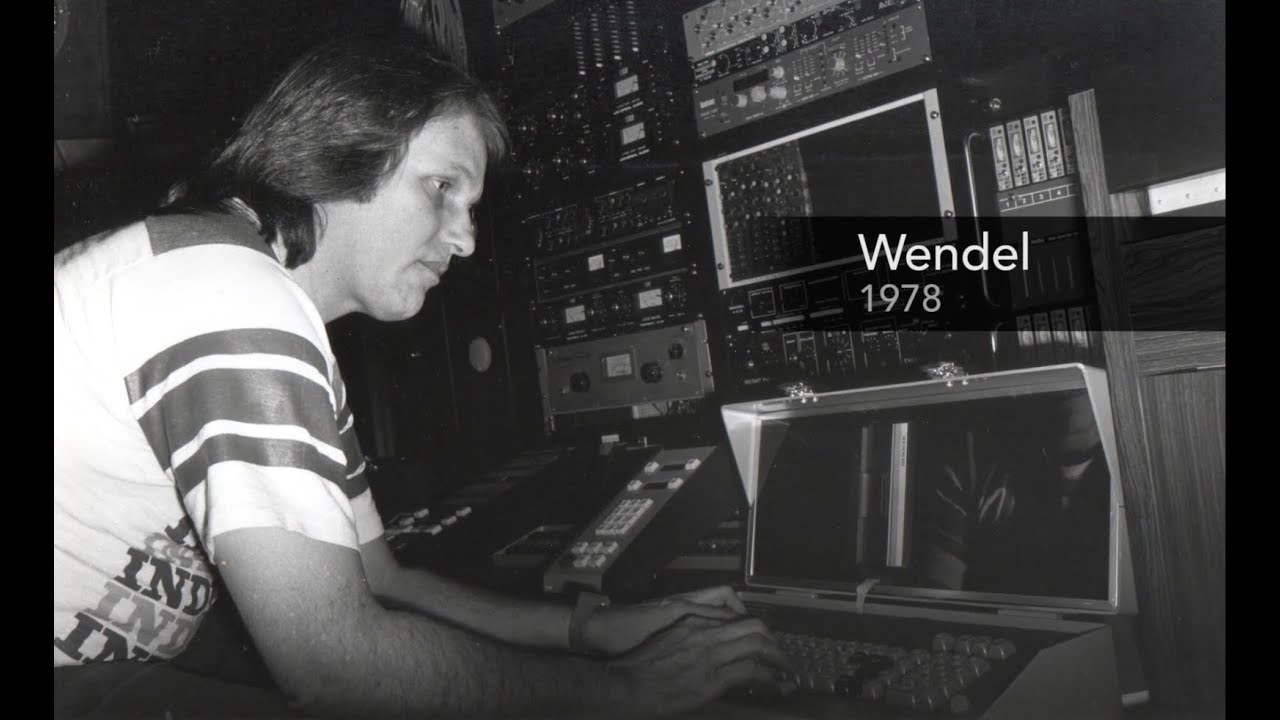

As documented in the liner notes for the 2000 reissue of Gaucho, Steely Dan’s chiefs recalled; “Roger Nichols had this toy - we thought of it as a toy - but one day he came to work and told us that the toy had become a man - one helluva man, in fact. A very talented man. A steady man. A man for all seasons - call him Wendel.”

What Nichols had come back with was in actuality a very early digital drum machine.

Although the technology unerpinning this 125kHz/12bit sample-rate machine was fairly basic by today's standards, Wendel enabled Fagen and Becker to replace the individual drum components recorded by live drummers, re-assemble them and try different, adjusted patterns without the time-sink of having to re-record.

“Wendel can be used to repair or to augment rhythm tracks in an almost infinite number of ways,” asserts Nichols’ operating manual for his device. “Wendel will not easily become obsolete because the entire operating system is loaded into the system each time it is used.”

Results weren’t instantaneous, however.

Roger (nicknamed 'The Immortal' after miraculously surviving electrocution by some un-grounded tape machines) had to program the machine using the ‘unforgiving’ (and now obsolete) 8085 Assembly Language, in which all the tiniest details of the drum sound had to be programmed into the machine one line at a time.

Allegedly it could take up to half an hour of coding to yield a single snare hit. As the manual (which you can read here, preserved by RogerNichols.com) indicates, it’s pretty perplexing to all those without a degree in late seventies computer science.

“Roger’s machine did not even have any switches; it only had a regular computer keyboard, and he had to type all these bytes out, huge lists of numbers, which took him 20 minutes, and at the end, he would hit Return, and we heard this one snare. It took so long,” Donald told Sound on Sound.

"There was no such thing as MIDI then," Nichols said in a speech. "So, we just put the click on tape, and have the click trigger the computer. Then we'd have to go back and do a second pass and do the snare drum. Another pass and do the hi-hat. Then we'd listen to all three of them together."

Although early drum machines were around at the time, the typical hi-hat sound was usually represented by an unrealistic ‘whoosh’ effect. Not so with Wendel, which offered 16 different hi-hat samples - adding that long-sought human player aesthetic.

In those days, computer memory was tiny, and its cost was at a premium. Storing high quality samples, therefore, was a tall order. According to Steely Dan Reader, one crash cymbal cost $12,000 worth of RAM.

But persistence paid off, and Wendel would prove its mettle. The eventual results delighted Donald and Walter. Wendel would be the architect of the drum sounds of key Gaucho tracks Hey Nineteen, Glamour Profession and My Rival and, for its efforts, this pioneering device would receive a platinum record following the million copies of the album sold upon its release on November 21st 1980. Nichols (and Wendel) would also bag a Grammy for the engineering of the record.

Building on this first successful deployment, the 16-bit Wendel-II was utilised on Donald Fagen's Nightfly album and, in 1984 the Wendel-Jr playback unit was released. Sadly, its creator Roger Nichols passed away in 2011, but Wendel remains enshrined in history as a significant step forward on the journey towards modern music production.

As Steely Dan’s pioneering pair reflected in the album’s liner notes, “[We] ended up adding perhaps 7 or 14 months, all told, to our already Augean labors, and hundreds of thousands of dollars to our monstrously swollen budget. And so was born the era of sampled drums and sequenced music - "The Birth of the Cruel", as we now think of it. History - read it and weep.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.