"What were the skies like when you were young?": How The Orb's Little Fluffy Clouds showed the world that sampling could be an art form

The story of the blissfully psychedelic bricolage that launched The Orb's career, introduced ambient house to the masses and even prompted a lawsuit from Rickie Lee Jones

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the 21st century, sampling has become an essential technique in pop music’s toolbox: from Britney Spears’ Toxic to Sabrina Carpenter’s Espresso, modern chart history is lined with hits built on snippets of other songs or ready-made loops from commercial sample packs.

Back in the ‘90s, though, sampling was still a new frontier in music-making. Having entered the vocabulary of mainstream music in the ‘80s via the groundbreaking efforts of American hip-hop producers, sampling's abundant creative potential inspired a generation of electronic musicians on the other side of the Atlantic, armed with bold new ideas and music technology that was becoming more sophisticated and affordable with each passing year.

Artists like Orbital, The Prodigy, Aphex Twin, Fatboy Slim and Moby all played a decisive role in pushing the boundaries of what sample-driven music-making could do. But amid this golden age of sample-based creativity, one widely beloved and blissfully psychedelic track stands tall, symbolizing the alchemical magic of sampling’s ability to collide disparate sounds from different worlds together to create something thrillingly new: The Orb’s Little Fluffy Clouds.

The disparate sounds in question? An interview clip of American singer Rickie Lee Jones dreamily reminiscing about the “beautiful skies” and “little fluffy clouds” of her Arizonian childhood, a Pat Metheny performance of Electric Counterpoint, composer Steve Reich’s minimalist masterpiece for electric guitar, and a harmonica sample from Ennio Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West. Throw in a time-stretched drum break from a Harry Nilsson tune, a handful of sound effects and a bubbling synth line, and you’ve got the recipe for Little Fluffy Clouds.

In the three-and-a-half decades since it was founded, The Orb has been made up of a shifting line-up centred around one consistent member: Alex Paterson. While the group began as a duo with Jimmy Cauty of The KLF, the pair unceremoniously parted ways in 1990 during recording sessions for what they thought would become The Orb’s debut album, before Cauty was replaced by Martin “Youth” Glover, a childhood friend of Paterson’s and a founding member and bassist of the band Killing Joke.

“Jimmy and Alex were making an album called Space when they had a big argument,” Glover recalled in a 2016 interview with The Guardian. “Jimmy stormed off, took all of Alex’s bits off the record and released it under his own name. Alex was mortified. I told him not to worry – we’d make a record that was even better.” That record was Little Fluffy Clouds, a song that helped to launch The Orb’s career, introduced ambient house to the masses, and even prompted a lawsuit from Rickie Lee Jones.

But Paterson and Glover couldn’t have made Little Fluffy Clouds without the help of one of their fans, an enterprising listener that mailed them a cassette tape with the very same sample combination that became the song’s foundation. “The cassette had Pat Metheny on one side and the Rickie Lee Jones interview on the other,” Paterson told Sound on Sound in 2011. “It came with a note saying something along the lines of, 'You guys are going to have to make a track out of this. It is definitely Orb material.'”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

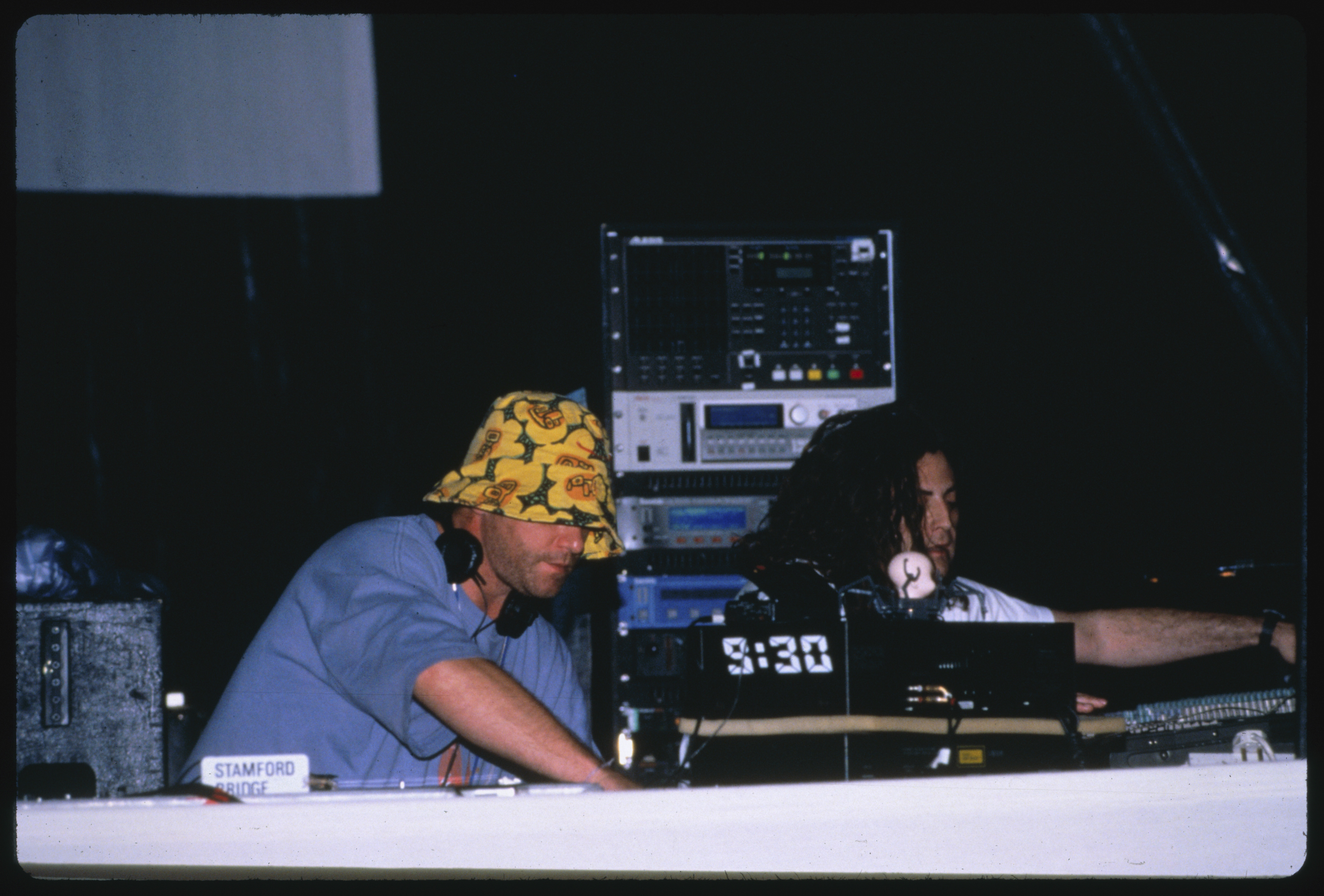

With this germ of an idea in hand, Paterson and Glover put together a demo for Little Fluffy Clouds in a bedroom studio in their Wandsworth flat, with the rackmount Akai S700 on sampling duties. Layering multiple samples together in a freeform and improvisational creative process, they drew inspiration from wide-ranging DJ sets they’d performed at London’s Heaven nightclub.

“We set up the first chillout room there, playing ambient music and film soundtracks,” Glover recalls. “No one danced; they were all lying down. There were five or six turntables, and we’d play different records all at once. We thought: ‘Why don’t we do this in a studio?’”

Alongside the two original samples, the duo pulled in an eclectic mix of sounds: the Morricone harmonica and the Nilsson drum break were joined by sound effects from the BBC archives and snippets of Paterson being interviewed on radio. The evocative line that opens the track ("Over the past few years, to the traditional sounds of an English summer - the drone of lawnmowers, and the smack of leather on willow - has been added a new noise...") was lifted from BBC Radio 4 programme You and Yours.

With their bricolage of samples arranged into a demo, Paterson and Glover decamped to Bunk, Junk and Genius - a studio a stone’s throw away in Fulham – to finish off Little Fluffy Clouds with the help of Kris “Thrash” Weston, a collaborator that would spend several years in The Orb’s line-up as a full-time member. “The track evolved over the course of about six months,” Paterson told SoS. “Working in a proper studio was different to being in the bedroom, where we could waddle in and out whenever we felt like it.”

Weston helped to engineer the track and program the drum pattern, a beat constructed out of a slowed-down drum break pulled from Harry Nilsson’s 1990 song Jump Into The Fire. “My brother was a big Harry Nilsson fan, and I always wet myself when the drum solo came on,” Paterson told Electronic Sound in 2018.

“When we were sampling things for Little Fluffy Clouds, Youth said, ‘Do you know any good drum breaks? ‘Actually, I do – this one’. It’s just a short section programmed to work in such a way that it gives whatever else you want to put over the top even more oomph. The whole structure of the song is based on that loop, really.”

"If anyone actually knew where the drums on Little Fluffy Clouds came from, they'd all just die, but I'm not at liberty to tell"

Though The Orb’s use of the Nilsson break is now public knowledge, Paterson kept the origin of the drums a secret for many years, telling Remix Magazine in 2001: “If anyone actually knew where the drums on Little Fluffy Clouds came from, they'd all just die, but I'm not at liberty to tell. Record companies have always warned me, ‘Don't tell anyone where you got your samples until we get them cleared!’”

Paterson later told Electronic Sound that the sample would’ve remained a secret, if only he hadn’t revealed his methods after a few too many pints at the pub: “No one would have ever known that if I hadn’t told someone when I was really drunk one night”.

With their kaleidoscopic melange of samples in place, Glover added a keyboard riff and a bassline to round off the track and bring the elements together as a coherent whole, an aspect of the writing process that Paterson says was no easy task: “One of the main challenges was disguising so many things to make the track have its own identity and getting so many different areas of samples to stick together”.

Another challenging moment in the song’s creation was trimming down its runtime to create the four-minute version first released as a seven-inch single. (The Orb’s debut single, A Huge Ever Growing Pulsating Brain That Rules from the Centre of the Ultraworld, stretched to 19 minutes.)

“I thought it was too poppy, but people loved it,” Paterson says of Little Fluffy Clouds’ radio edit. And loved it they did. Released in late 1990, the song rose to No 87 on the UK Singles Chart, a level of success that few could have predicted for a relatively unknown group working in a then-nascent genre, building tracks from obscure samples using experimental production techniques. The song later featured on The Orb’s debut album in 1991, before a 1993 re-release reached No 10 in the UK.

Little Fluffy Clouds may have helped to launch The Orb’s career, but its success brought its own problems. Back in the ‘90s, when sampling had yet to become the established practice that it is today, The Orb held a decidedly laissez-faire attitude to copyright, a “punk rock attitude” that Paterson sums up as “if you want something, you can come and get us”.

That’s exactly what happened when Rickie Lee Jones’ record label heard Little Fluffy Clouds; threatening The Orb’s label with a lawsuit, they ultimately settled for a $5,000 payout. (Years later, she candidly referred to The Orb in an interview as “those fuckers”.)

“We got a letter from Steve’s lawyers, but he was a proper gentleman”

Thankfully, Steve Reich’s approach was a little softer. “We got a letter from Steve’s lawyers, but he was a proper gentleman,” Paterson recalls. “He wanted 20 per cent of the publishing, but only from the day he found us, not from when it was released, and he also asked us to remix a track for him in exchange. We obliged, very courteously. I have so much faith in artists like that.”

With their brazen, fast-and-loose approach to sampling, The Orb raised more than a few eyebrows back in the ‘90s, drawing criticism not only from those who challenged the legality of their musical plundering, but also those who questioned its artistic value. Many listeners and publications sneered at sample-based music, framing it as lazy and inauthentic – not like the “real music” of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Thanks to pioneering artists like The Orb, public perception of sampling has since evolved, as audiences have grown to realize that samplers are instruments like any other, and that the way that you use a sample is a creative act in and of itself. "I've always thought that plagiarism is creative," Paterson once said. "In no way did I consider it to be destructive, especially if you can twist that sample and make it become something else."

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.