Trackers, video games, soldering irons and bitter rivalries: 5 reasons why the '80s was the ultimate decade for computer music-making

If you thought the '80s was just about big phones and haircuts, think again; it was also the start of a music production revolution

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it comes to music production, the '80s will probably be remembered for great synths, rubbish synths, great music and terrible music. What it probably won’t be remembered for is its contribution to the history of computer music making. This is, frankly, wrong. Here's why…

I started making music properly with a computer towards the end of the 1980s with an Atari ST, but I was actually dabbling by way of a ZX Spectrum much earlier in the decade.

And plenty of other socially-challenged people like me were spending way too much of this time on their own, tinkering with various Commodores, Oric Ones, BBC Micros, Jupiter Aces and more to make them produce sounds.

The Mac and the PC were born in the decade too, of course, but I’m talking about the other home computer revolution, in which small companies could make computers that rocked. This was a time well before Ableton Live, the iPad, cloud and phone, and people like me would dig deep into coding and electronics to make… well, often not very much.

People like me would dig deep into coding and electronics to make… well often not very much.

But boy did we get into the guts of these machines. At the start of the decade I was loading games into a ZX81 with a dodgy 16k RAM pack, all by cassette. By the end, I could program in around eight different languages including BASIC, Forth, Fortran, Pascal and C.

And as amazed as I am looking back that I could do this, it wasn’t uncommon. Everyone I knew could program computers, although ‘everyone I knew’ went to a dingy computer club on a Thursday evening where very few words were exchanged, just binary.

We didn’t rely on other people to write the code for us if we wanted to make music; we did it ourselves, and even built the hardware. By the late '80s I was even making MIDI interfaces for ZX Spectrums. Admittedly, the first one I built blew up both devices, but my point is that if you dug deep in that decade, computer music was there to be had.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Of course, my spectacles may be rose-tinted, but it seems that kids today would rather Snapchat than solder, TikTok than tinker. But before I get too 'things were better in my day', that's enough about why the '80s was my computer music decade, because here are five reasons why it could actually be yours, too.

1. Video games and music

Music started to be proper 'computer music' in the 1980s. Yes, there were synth wizards in the 1970s, all cloaks and solos, but the popularity of the synth exploded in the 1980s and gave us a brilliant first flavour of electronic music, as we talk about in this feature on the synths that defined the 1980s, and as we discuss one of the most important '80s synths, here.

Throughout the 1980s, computer game music became more complex, memorable and, in many cases, iconic.

But it wasn't just the synth that exposed us to 'computer music'. If you were anything like me, your first introduction to electronic sounds was probably in a tacky seafront arcade, shovelling pocket money into what seemed like an endless line of exciting arcade games. The music in these games was (almost) as important as the gameplay, and throughout the 1980s, computer game music became more complex, memorable and, in many cases, iconic.

And there were even moments in the '80s when the synth-pop and video games worlds collided…

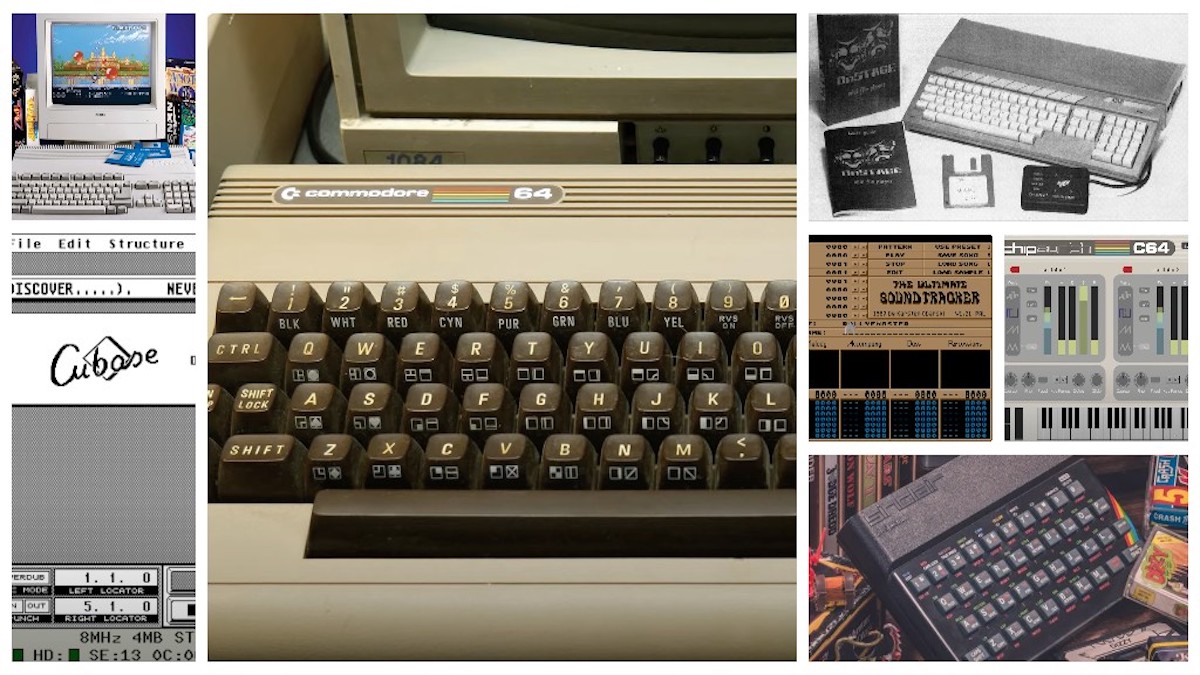

The music made by those early video game and computer chips lives on today in the chiptune scene. A large chunk of credit for this must go to the Commodore 64 computer and its SID (Sound Interface Device) chip; this was one of the first computers to be able to generate decent music across several channels.

A large chunk of credit for chipmusic must go to the Commodore 64 computer and its SID (Sound Interface Device) chip.

The fascination spread via handheld gaming devices like the Nintendo Game Boy, which even has its own titles (such as LittleSoundDJ) specifically for composing this 8-bit style music.

Chiptune music can be created with ease now, and in a variety of ways. On a basic level, you could use simple square and triangle waves, a noise generator and low bit-rate samples in any DAW. However, there's such a thriving scene out there – with artists like Remute creating complete chiptune albums – that plugin manufacturers have been quick to produce chiptune plugins that cater to it.

Plogue's chipsynth C64 which emulates the SID chip, is one of the latest.

Another piece of notable chipmusic software is Deflemask. This 'tracker' software creates music very much in a way that '80s tracker programs did, stretching the audio capabilities of the then home computers to create complete tunes (more on these below).

So video games in the 1980s were just as important to the history of computer-based music as the synthesizer. And both got us so excited listening to it that we wanted to create it. Luckily, the 1980s gave us the tools to do that, too.

2. The 'home' computer

The 1980s were the dawn of computing – at home, anyway. As I mentioned above, there were many machines released that barely cost more than $/£100; the first computers designed for home use, and machines that would (eventually) enable you to create both graphics and sound.

Way before any Mac versus PC nonsense, there was bitter computer rivalry in the early 1980s – as if we didn’t have few enough mates as it was.

Incredibly – and way before any Mac versus PC nonsense – there was bitter computer rivalry in the early 1980s. As if we didn’t have few enough mates as it was, we would decamp to one side of the computer abyss and not speak to anyone who didn’t own our particular machine.

If you were in the ZX Spectrum camp in 1982, as I was, you pretty much ignored Commodores, because they were owned by fancy-pant rich kids who needed all the extra colours and sound the machines afforded.

The first such Commodore I recall was the VIC-20, very much the 8-bit yin to my Spectrum yan. I hated it because it was basically a lot better than my rubber-keyed Sinclair. It had proper keys and looked like an office computer. Capable of four (some say five) sound channels, you could ‘Poke’ pitch, octave, volume and even add noise.

With a ZX Spectrum you could basically ‘Beep’ the duration and pitch and that was it, although it and the VIC-20 would both get their own tracker titles as you can see here.

This meant the Commodore was already a more capable sound creator than anything I used, the noise giving it an often rhythmic and grungy quality. Basically, it was a Schmidt synthesiser compared to my Wasp.

However, the importance of both machines was that they made sound and you could change it. That's called 'composition' in my book. Pop charts here we come.

3. Trackers and the Amiga

Another even bigger '80s computer rivalry – with double the bits making it so – was the Atari ST v another of the Commodores. (No, not those Commodores, although Nightshift was another great thing to come out of the '80s.) This time it was the Commodore Amiga. And so big a battle was this in the '80s, that the fallout is still with us today, and you can probably still find many a platform or forum on which to pick a fight on either side.

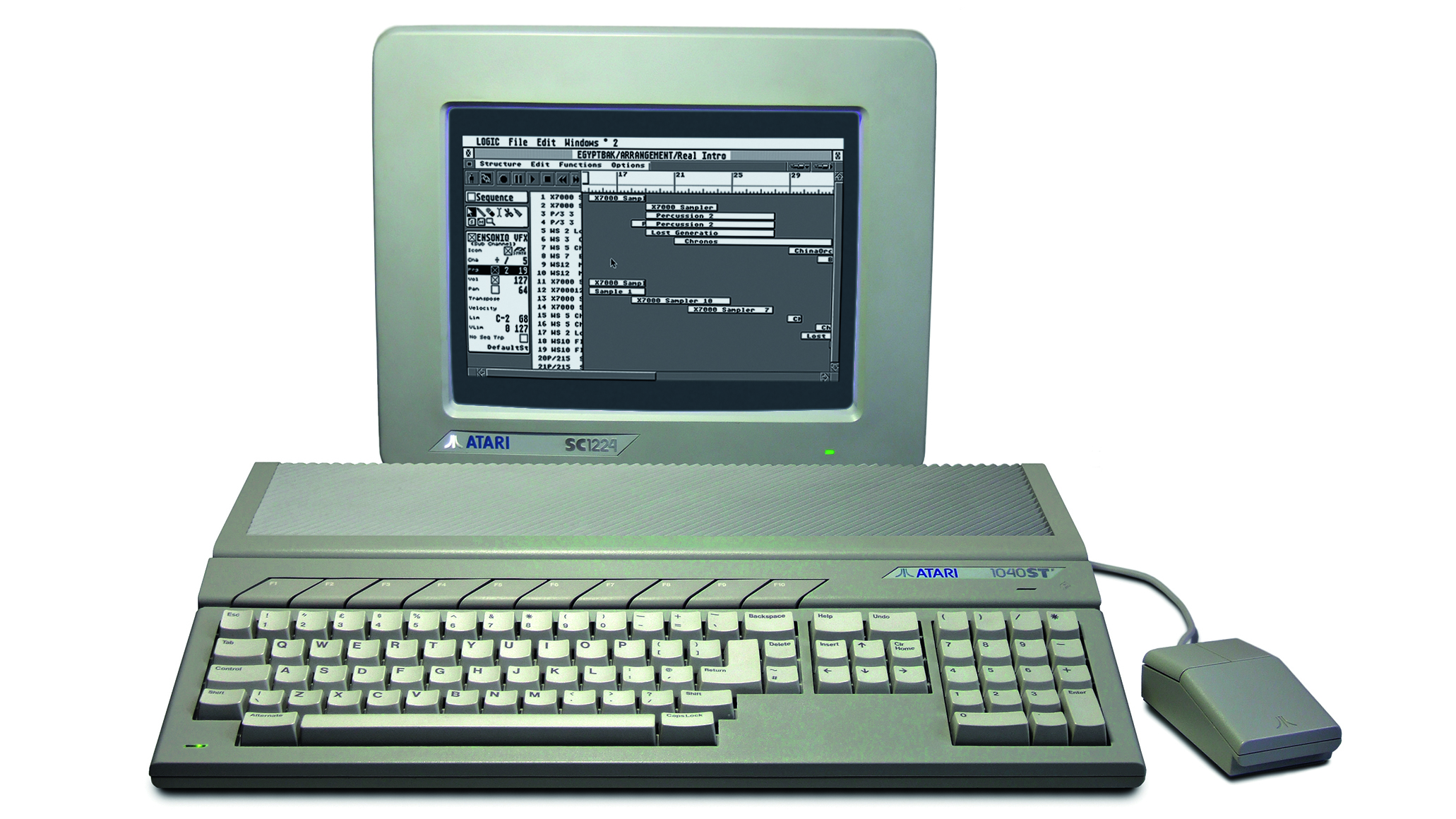

I fear I was on the losing side again here with my later '80s computer choice, the Atari ST – especially when listening to side-by-side demos of their sonic capabilities now.

And the specs of both machines appear to back up that fear. The Amiga had four voices and could play 8-bit PCM waveforms and the Atari ST had a 3-voice chip that could play square waves. Some might say - Ok, they did say - that it was a generation behind.

As both computers strove for supremacy, they ended up becoming the solid base on which much of our computer music making stands today.

However, as wrong-sided as I might have been, this computer rivalry ended up getting so big that, as both computers strove for supremacy, they ended up becoming the solid base on which much of our computer music making stands today.

Both had the first proper generation of powerful – for the time – music-making applications. The Amiga’s big draw was the release of The Ultimate Soundtracker, developed by German computer wiz Karsten Obarski. (Not the first, nor last, German to be involved in computer music history.)

This 1987 title helped spawn the whole tracker/MOD music scene – oft used to create those chiptunes we talked of earlier – and one which is frequently cited as one of the most important developments for computer music.

Trackers could create module (MOD) files which initially included four tracks of music via the Amiga’s four channels, and while they sound complex in terms of their operation – and look like spreadsheets – you could make amazing tunes on an Amiga with them, and they made music creation a lot easier than it was before. It was early sequencing, Excel style.

While Tracker music did spread to other platforms, and even earlier machines, it is the Amiga on which it made its name, and it's a name that is still influencing music today. Polyend’s Tracker, for example, is very much a software tracker in hardware form.

4. MIDI and the Atari ST

While the Amiga had – OK, I admit it now – the looks, the sounds, trackers and the cooler users, the Atari ST, my choice, had MIDI. Yes you could add MIDI to the Amiga, but with a couple of MIDI ports built-in – and to this day no-one seems to know why – the ST became the first conventional home computer for music making with software titles like C-Lab's Creator and Notator, and Steinberg's Pro-24 and Cubase.

With a couple of MIDI ports built-in – and to this day no-one seems to know why – the ST became the first conventional home computer for music making.

The ST became the central hub of a studio, in fact. Some say this was possibly helped along by the rise in software piracy, but I wouldn't know. My most daring activity was that, yes, I didn’t pay for my copy of Cubase, but that was only because my chosen music dealer sent me two copies by accident, so I sold the spare one.

Either way, I used my Ataris ST as my base for music making from the late '80s well into the '90s. It was a rock-solid machine that people still talk about with tears in their eyes today.

5. The software

1983 was the year that MIDI first rolled out, giving devices like the Atari ST and the DX7 ways to connect together. But you also needed something to introduce them to one another and make wonderful music, and that was why the DAW came along in the same year.

You needed something to introduce MIDI devices to one another and make music, and that was why the DAW came along.

Keyboard player Manfred Rürup and engineer Karl ‘Charlie’ Steinberg first had the idea of a MIDI-based sequencer in 1983 just after MIDI came out – talk about being on the ball – and so began a company called Steinberg.

Its first product was the 16-track sequencer, Multitrack Recorder, for the Commodore 64. That became Pro-16, then Pro-24, Cubit and eventually Cubase. By way of the Commodore 64, Atari ST, and Commodore Amiga, that software became the platform we use today on our Macs and PCs. And if you used Cubase on the ST, this video will take you back.

Incredibly, Logic was also developed in Germany but slightly later in the mid '80s. It began life as a Commodore 64 sequencer called C-Lab Softtrack 16+, which then became C-Lab Creator and Notator for the Atari ST. These were more pattern-based than DAWs you'd recognise today, with blocks of MIDI data creating arrangements.

The C-Lab developers, Gerhard Lengeling and Chris Adam, would go on to form Emagic in 1992, and release Notator Logic for Atari, Mac and PC, which eventually, of course, became Logic and then Apple Logic Pro for Mac only in 2002 (it's now also available on the iPad).

The '80s were important after all!

So you see, the '80s should be given a lot more credit in the history of computer music making. History might well remember the decade for its shoulder pads, soap operas, greed, mullets and synth jams like this…

… but in truth there was an army of musicians ready to embrace the computer for its music playing and creating potential, even though it was an army that really didn't talk much to one another.

Andy has been writing about music production and technology for 30 years having started out on Music Technology magazine back in 1992. He has edited the magazines Future Music, Keyboard Review, MusicTech and Computer Music, which he helped launch back in 1998. He owns way too many synthesizers.