“It’s unfamiliar, intimidating, and seemingly impenetrable for producers raised on DAWs like Ableton Live - but it can unlock a whole new world of creativity”: I tried a music tracker and it rewired my brain (in a good way)

Beloved by artists from Aphex Twin to Deadmau5, trackers swap the trusty piano roll for a text-based, vertically-scrolling interface that looks like something out of The Matrix. Let's find out how deep the tracker rabbit hole goes

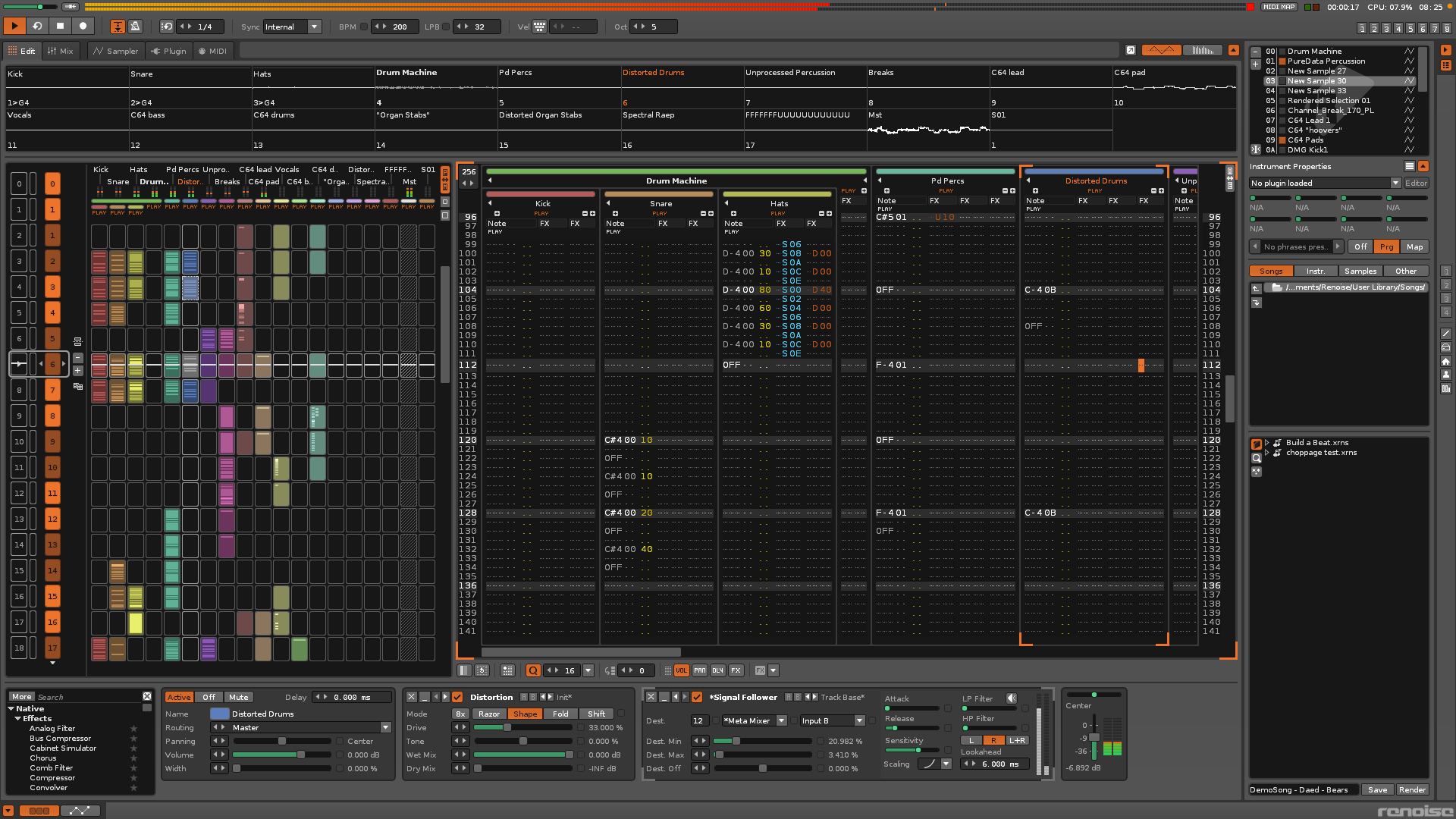

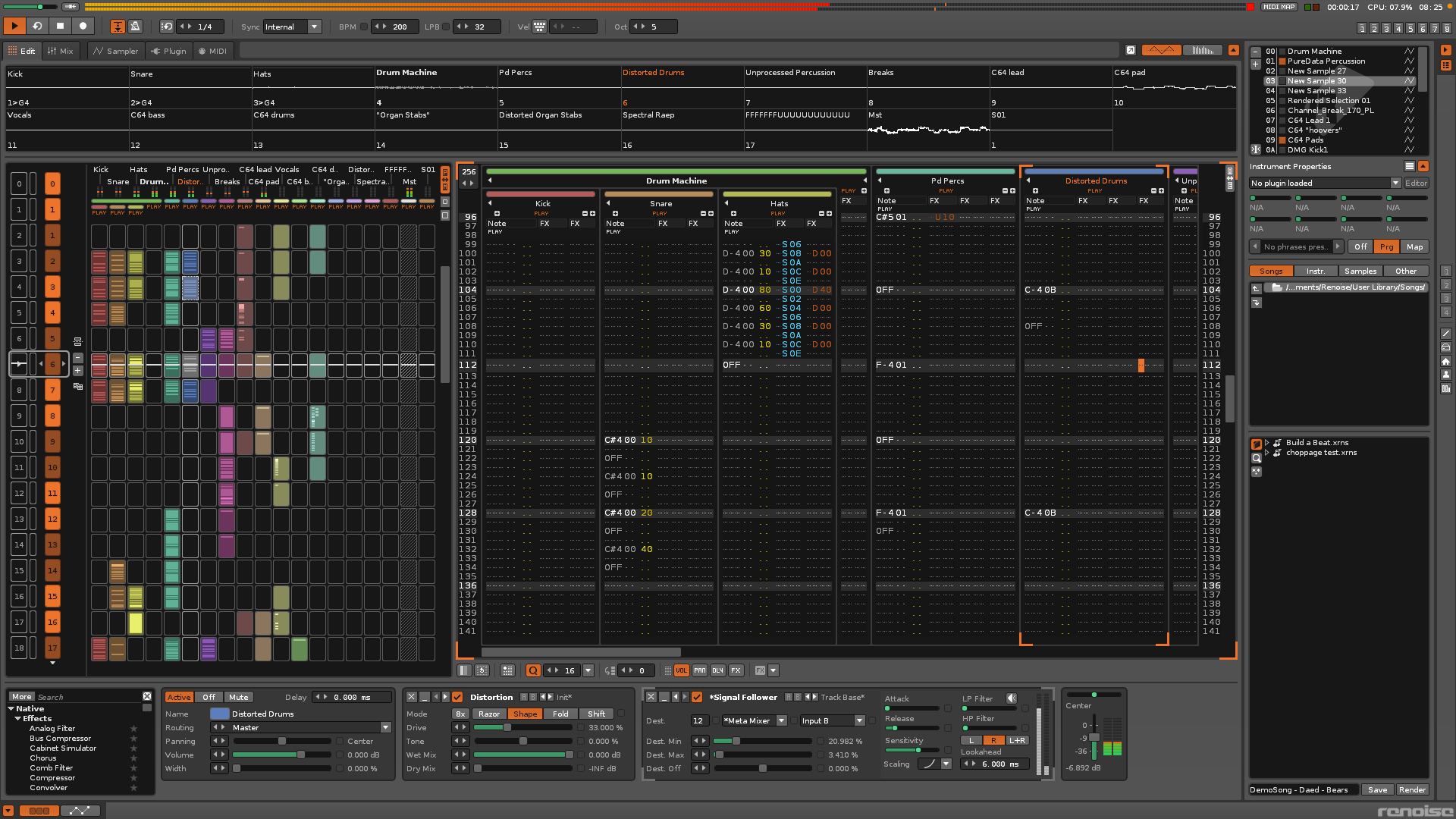

My computer screen is awash with numbers and letters careening upwards like The Matrix in reverse. With every beat, my ears are assaulted by a high-speed flurry of notes, sample chops and effects changes, everything happening much quicker than I ever thought possible.

Graphic bars have been replaced by letters and numbers, parameter values represented by the cryptic hexadecimal system. I've been transported to another dimension of music production and I’m barely in control: I’m programming with a tracker and I’m loving every minute of it.

Most music sequencers use some kind of left-to-right arrangement. Whether that’s the intricate hopscotch of a step sequencer or the endless piano roll of a digital audio workstation, for the most part, sequencers tend to advance horizontally.

Not trackers. They buck the trend by scrolling upwards. They also replace graphic notes on a bar with lines of numbers, like computer code with no GUI veil. It’s unfamiliar, intimidating, and seemingly impenetrable for producers raised on DAWs like Logic and Live.

And yet - working with a tracker can yield surprising and unexpected results, unlocking whole new worlds of creativity for those brave enough to take the red pill. Are you ready to see how deep the tracker hole goes?

What is a tracker?

The first tracker was Ultimate Soundtracker in 1987. Released for the Commodore Amiga by EAS Computer Technik, it gave users access to a then-fairly generous four channels of audio. Crucially, these were 8-bit samples pulled from the Amiga’s Paula audio chip. This focus on sampling in trackers continues to this day.

Four channels of audio expanded to eight with the release of RBF Software’s OctaMED in 1991. More than just granting users access to the internal sound chip, however, OctaMED allowed producers to sequence external gear via MIDI. OctaMED was soon adopted by hardcore and fledgling jungle producers for its ability to create intricate sequences of chopped breaks, either from hardware samplers like the Akai S-950 or via the Amiga itself.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

DJ Zinc used OctaMED for Super Sharp Shooter, and Aphrodite famously made his early records with two Amiga 1200s paired together. Modern jungle producer Pete Cannon still uses an Amiga to produce, telling Polyend, maker of the Tracker hardware sampler: “I love trackers for chopping. I still use the Amiga for its sound and the nostalgia it gives me.”

Trackers soon made the jump to PC, upping track counts as they evolved. Impulse Tracker, released in 1995, had 64 channels. Both Deadmau5 and Machinedrum cut their teeth on Impulse Tracker and the latter actually revisited it on his album, 3FOR82. And of course, Aphex Twin made the most of the tracker PlayerPro for Drukqs, as you can see in a video he shared for album highlight Vordhosbn.

Usually confined to computers, trackers have also made the jump to hardware in recent years, with both Tracker from Polyend and Dirtywave’s M8 bringing the tracker/sampler workflow to standalone devices. LSDJ, an unofficial sequencer for the Nintendo Gameboy, transforms the portable gaming device into a tracker and was instrumental in the formation of chiptune as a genre.

Renoise: the tracker DAW

Which brings us to Renoise, and my introduction to trackers, music production’s parallel universe. First released in 2002, Renoise has developed into a fully-fledged DAW complete with plugins (AU and VST), MIDI for controlling external instruments, and even ‘tools’, user-programmable scripts that add functionality to the program, like Max For Live devices in Ableton Live.

The main difference between Renoise and other DAWs is, of course, the tracker sequencer. Where most DAWs have a piano roll, Renoise has the vertical-scrolling tracker window. And, rather than a vertical timeline, you arrange songs by assembling blocks of sequences in a horizontal fashion.

As well, being a tracker at heart, the Renoise workflow is centered on working with samples, with the sampler an integral part of just about everything. Of course, you can create tracks with third-party soft synth plugins, but what look like Renoise factory ‘instruments’ from the outside are actually just samplers at their core.

Lastly, although Renoise supports MIDI controllers like other DAWs, trackers have always been computer programs first and foremost; they work best when your interface is a computer keyboard. Arrow keys, F keys, and a separate number pad: this is how you interact with a tracker, and the fastest way to work with Renoise.

Taking the red pill

I was sat in front of my computer, staring at Renoise in bewilderment. I had a demo song loaded up and running, a 200BPM breakcore monster called Bears by someone named Daed. The tracker grid launched upwards in a riot of numbers and letters while a flurry of beats and bass jettisoned from my monitors. What had I gotten myself into? I couldn’t make heads nor tails of what was happening, my four decades of music production experience rendered suddenly useless.

It didn’t help either that the vibe was all so ‘personal computer.’ Trackers come from a world of hackers and computer enthusiasts. For me, computers had only ever been a tool to do the things I wanted, like writing and making music. I have also only ever used a Mac, while Renoise looks like a Windows port. And all the numbers! I’m a words guy, right-brained: maths gives me panic attacks. I was, in all honesty, intimidated.

Take a moment, take a breather. I stopped the demo and tried a few others instead; tech house, ambient, dubstep. This was easier to understand, the pace less manic, the workflow less cryptic. I started clicking around at my leisure, figuring out the lay of the land. Here is the sampler screen, here’s the mixer. The effects are arranged at the bottom of the screen like Ableton Live, the mixer like Logic. I can do this, I said to myself.

Rewiring my brain

The big hurdle was, of course, the tracker sequencer itself. There’s always a learning curve when switching DAWs. That’s to be expected. For the most part though, the differences are minor. The basic workflow, the general layout; they’re essentially the same. Roadblocks are small and soon overcome.

But Renoise. A tracker? This was not just learning a few new words, it was like diving into an entirely new language. I speak Japanese, and because of the vastly different grammar, the process of becoming fluent required laying down many new neural pathways in my brain. Renoise was asking the same thing of me. Not left-to-right but bottom-to-top. Not a piano keyboard but a computer keyboard. Even the way that musical events are numbered: not 1-16 but 0-15, so a 4/4 kick pattern gets notes on 0, 4, 8, 12 and not 1, 5, 9, 13.

This was not just learning a few new words, it was like diving into an entirely new language

And then there’s hexadecimal. Renoise (and trackers in general) use the hexadecimal numeral system to express parameter values. Each line in the sequencer has a position for the note (expressed as a letter and octave, such as C-4), the selected instrument number, and then what are called “effects.” These are for volume, pan and delay (what Renoise calls note offset). These amounts are expressed not in regular numerals but hexadecimal notation, for example 3E or FF.

What’s going on here? Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system that uses the numerical digits 0-9 and the letters A, B, C, D, E and F. By combining these two, you can go beyond what would normally be allowed by just two decimal spaces. Where the maximum would only be 99, with hexadecimal you can go all the way up to FF, or 256. It’s actually a clever - and rather elegant - way of squeezing a finer resolution out of a limited space. In theory. In practice, it can be very confusing - as I found out.

Back on track

But, like anything else, practice and repeated use leads to familiarity, and Renoise is no exception. By the third day of struggling with its vertical orientation, hexadecimal notation and other unfamiliar elements, I finally started to get the hang of it. At a certain point I turned off my MIDI keyboard controller and just used the computer keys, and here is when things really started to speed up for me.

Working with arrows and keys is so much faster than a mouse and piano

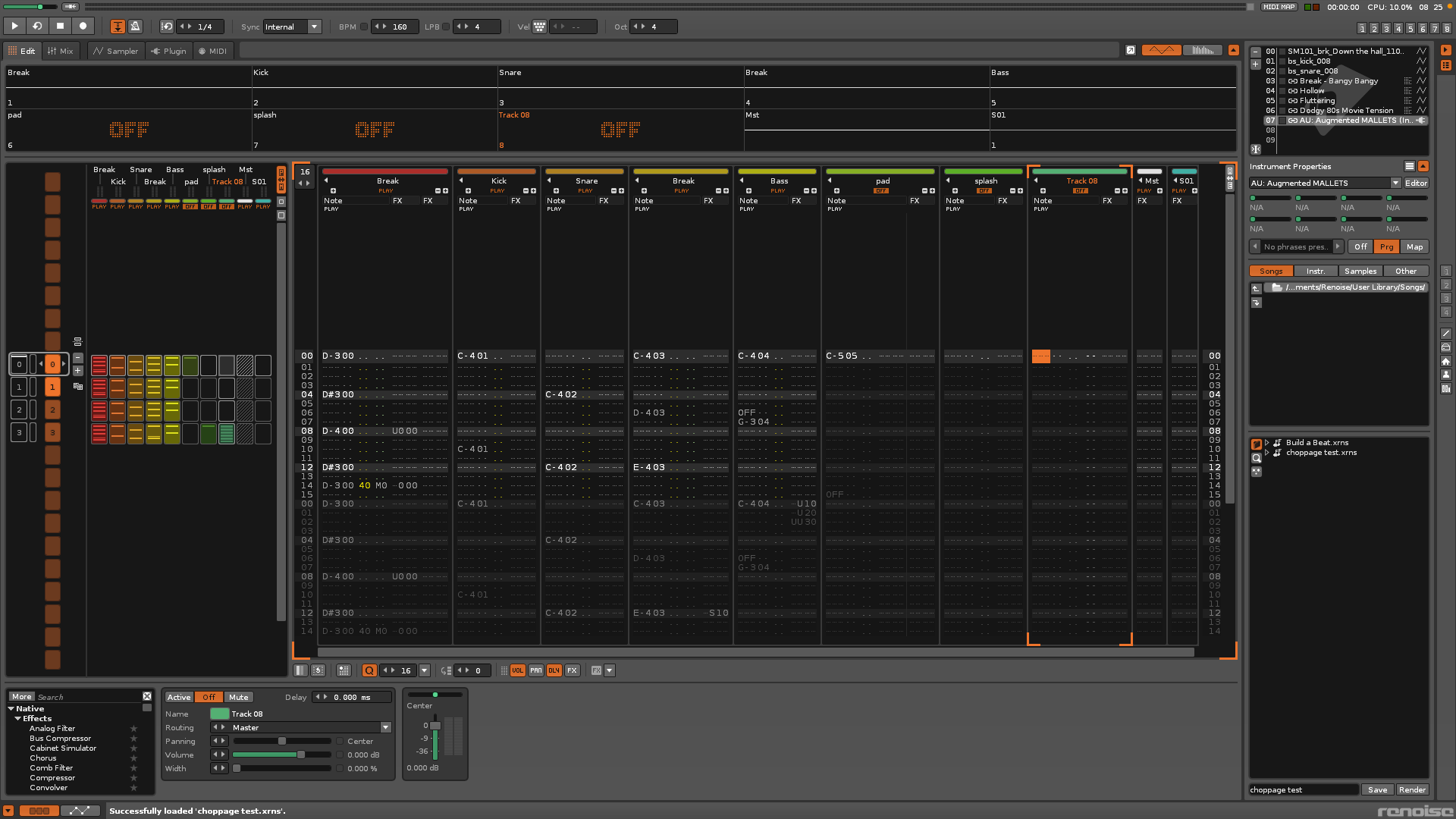

Working with arrows and keys is so much faster than a mouse and piano. With this new computer workflow, I was able to slot myself into the tracker mindset. It was like my brain started flowing vertically and thinking in terms of per-note parameter changes. Within a few hours, I had the beginnings of a not-terrible jungle track, something that I had always struggled to make in a traditional DAW to any degree of satisfaction.

By the end of the third day, I found myself grinning like Richard D. James on the Windowlicker album art as I banged out chopped breaks, pitch-bendy bass and gritty pads, all bolstered by Renoise’s superb built-in effects. I even had Arturia’s Augmented Mallets running in the tracker, playing a manic run of notes that I would never have programmed in a regular DAW.

Should you switch to a tracker?

I still have a long way to go in learning Renoise, but after a few weeks, I feel as if I have the basics down, and I can finally think in terms of its ‘language’. Will I be giving up Logic and Live in exchange for the tracker life? Probably not. While Renoise does some things extremely well - it chops breaks like nobody’s business and excels at abrupt structural transitions - it also has some undeniable drawbacks.

Renoise chops breaks like nobody’s business and excels at abrupt structural transitions - it also has some undeniable drawbacks

Being a tracker, it’s overly focused on working with samples. This is great for sample-based genres like jungle or hip-hop but when it comes to recording audio, you’re stuck using the sampler rather than recording to an audio track. There are ways around this, of course, but at the end of the day, they’re still just workarounds.

Better yet is to use Renoise in conjunction with other DAWs. Make your breaks in Renoise then export them to Live and continue from there, or sample soft synth sounds from Logic or FL Studio then compose within Renoise for the tracker vibe. You could even use Rewire to connect Renoise to your DAW of choice and work that way.

A few alternatives

If you like the idea of a tracker, or are a fan of the nostalgic sounds of ‘90s computer sampling, there are a few different ways to get the vibe of Renoise without committing entirely to a new DAW.

Redux is the sampler from Renoise (complete with tracker-style phrase sequencer) in a plugin format. This way you can utilize the powerful Renoise sampler and its unique approach to sample manipulation without fully committing to the tracker lifestyle.

Another option is Amigo Sampler from PotenzaDSP, an 8-bit sampler that recreates the crunch and funk of the Amiga’s sound chip in plugin form. There’s no tracker though.

Lastly, there are freeware music trackers available if you just want to test the waters. Try Milky Tracker or Schism Tracker, the latter of which is an open source reimplementation of Impulse Tracker, the software that Machinedrum and Deadmau5 learned on. If chiptune is your thing, try Famitracker.

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.