“You sacrifice things you love. I love my guitar”: How a journalist’s joke led Jimi Hendrix to set fire to his guitar for the first time

It was a ritual that would symbolise Hendrix’s esoteric allure, but the first night he did it, the incendiary act was quickly thought up backstage

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

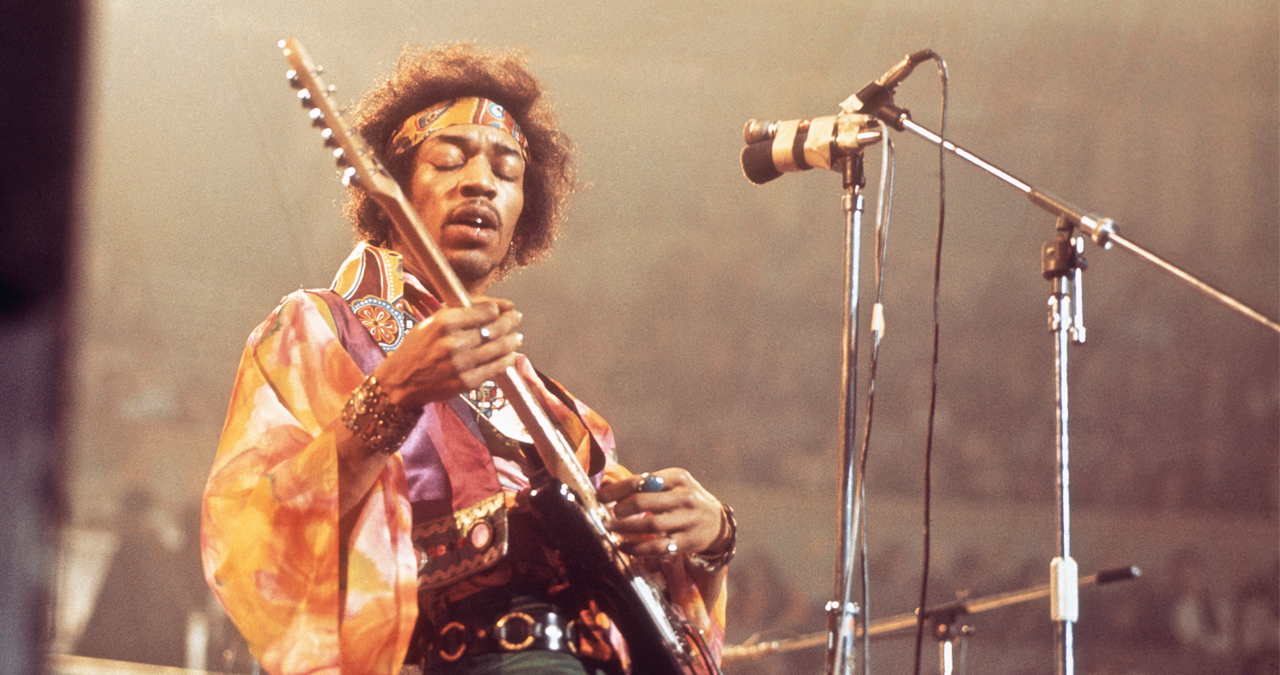

It’s an image that has become synonymous with the explosion of 1960s counter-culture; guitar demigod Jimi Hendrix lighting his guitar on fire at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967.

Hendrix's spellbinding act seemed to perfectly convey the spirit of an era where post-war rigidity was being ripped down - set ablaze you might say - by a new generation, with new ideas, fuelled by the spirit of revolution.

Yet despite its iconic, well-documented status in the Hendrix canon, Monterey wasn’t the first time that Hendrix had performatively abused his guitar in this way. It did prove to be the most enduring, by dent of it being enshrined in history by the godfather of live music filmmaking, D.A. Pennebaker, in his film Monterey Pop.

But the spectacle of Hendrix setting his Stratocaster ablaze had actually started back in his adopted home city of London.

Having moved to the UK capital in September 1966, Hendrix had already developed a name for himself amongst the cream of London’s coolest underground musicians and creatives. But it was the Animals’ bassist Chas Chandler who knew that this astonishing performer had the stones, and musical brilliance, to take the world by storm.

If only the record buying public would give this unpredictable, yet often sonically abrasive, artist a chance.

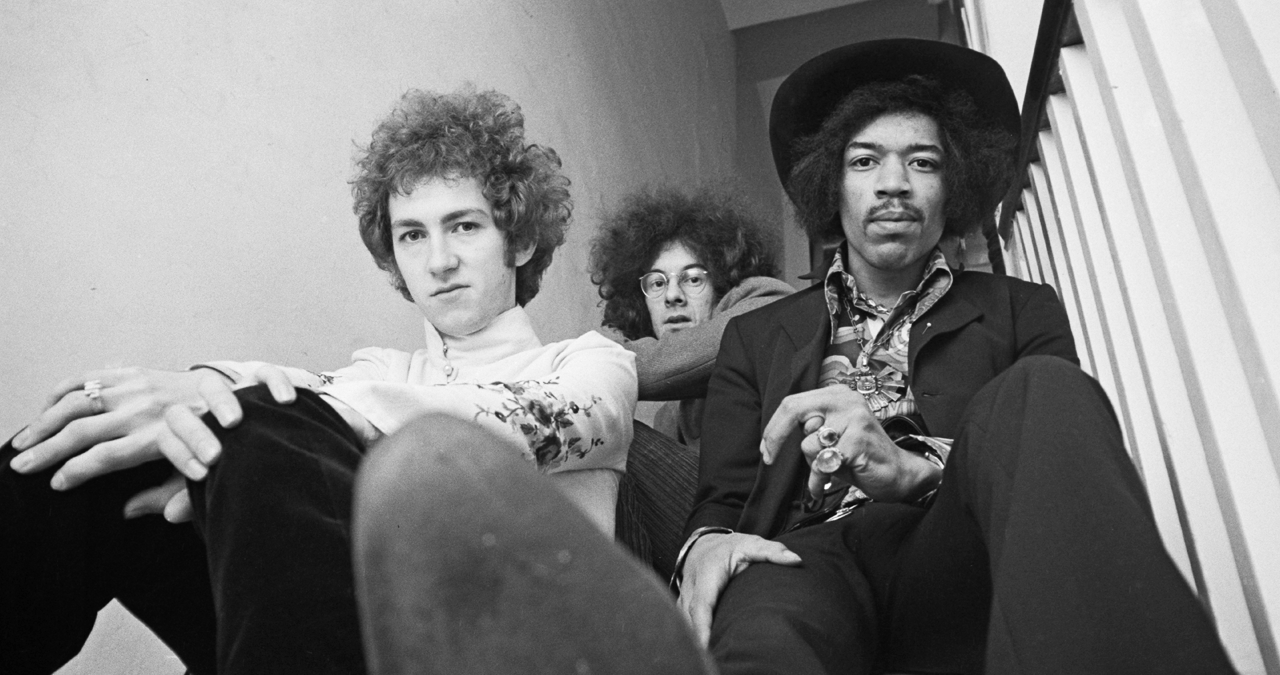

In early 1967, Hendrix and his band, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, were still on the ground floor when it came to getting on live bills - and therefore getting attention from a more widespread audience than the ‘happening’ underground scene proved to be an uphill struggle.

Jimi was a stunning live performer from the off, manipulating feedback, improvising divine solos gracefully and frequently prone to ecstatic, enrapturing freak-outs in front of his amplifier.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Music makes me high onstage, and that's the truth. It's almost like being addicted to music. You see, onstage I forget everything, even the pain,” Hendrix was quoted as saying in Starting at Zero: His Own Story.

For the youth of Britain, where Hendrix sought to make a name, there was an increasingly destructive energy in the air, best exemplified by proto-punks the Who. Pete Townshend was renowned and worshipped for his ferocious smashing of the guitar at the end of the Who's live shows.

Perhaps something a little more in this visceral vein was needed to catch the kids' attention.

Jimi, and his manager, knew that he’d need to do something rather extraordinary to turn the nation’s heads to his abilities.

On the first night of his first major UK tour, Jimi would light the spark.

However this wasn't billed as the kind of rock tour you'd expect today, this was a multi-artist, travelling roadshow package tour in support of the Walker Brothers, with Cat Stevens, Engelbert Humperdink, the Californians and the Quotations also on the bill. All of which were formally introduced by compere, Nick Jones.

NME journalist Keith Altham, had been an early convert to Hendrix’s brilliance, and begun floating around the band’s inner circle.

“The first time that I met Jimi was the time that Hey Joe go into the charts, which Chas [Chandler] helped along the way by buying a few extra copies,” Keith told Classic Rock magazine in 2015. “Then it took off on its own. He was very timid, quite shy, he punctuated everything with ‘so on’ and ‘ you know.’ In those days, journalists were much closer to the artists than they are now. They didn’t mind you going to their home or being with them in the studio as they worked, they weren’t so on their guard."

In his capacity as both journalist and entourage member, Altham recalled being present backstage before this first night at London’s Finsbury Park Astoria on March 31st 1967, where Jimi was set to kick of proceedings as the opening act.

Before the show, a group deliberation was had. How could Hendrix and the band take their profile to the next level, and grab attention from the wider music press beyond the four walls of the Astoria?

Altham recalled, in an interview with YouTube channel TheMyths, that Chandler turned to him and said,“You’re a journalist, what can we do to grab all the headlines this week?”

Altham, with a smirk, looked over at Jimi and responded, “It’s a shame you can’t set fire to your guitar.”

It was meant as a joke… but Jimi’s eyebrow raised at Keith's suggestion.

Hendrix and Chandler locked eyes in silence. This was happening.

Chas turned to the band’s roadie, Gerry Stickells, and told him to rush out to the nearest shop and grab some lighter fluid.

As the band’s five song set (which included Hey Joe and Purple Haze) came to its blistering conclusion, Hendrix launched into the scintillating - and apt - Fire. As Altham watched in the wings, Jimi reached for the fluid.

Putting his guitar between his legs, Hendrix doused the guitar’s body and promptly sparked up several matches. The heat was on.

But, try as Jimi might, the guitar wouldn’t take.

Altham was nervous, but had suspected that his (what he thought was) silly suggestion wouldn’t be possible.

“I knew you couldn’t set fire to a solid-state guitar, it just wasn’t gonna burn - unless you had a flamethrower or something,” Altham recollected.

But then Keith was taken aback when he to started to see fire begin to dance atop the guitar's body. The fluid had caught, surrounding the body itself with fire.

Hendrix leapt up in delighted surprise before seizing his now flaming axe as if it were the result of some arcane witchcraft.

An elated Hendrix whirled it above his head with wild abandon - not noticing that his hands were being lightly burned. The burns would require hospital treatment later that night.

"You thought, Christ, this is really what rock'n'roll should be. When Jimi set fire to his guitar I was absolutely stunned," remembered Polydor's George McManus in an interview with Classic Rock.

“The guy in charge of security [at the Astoria] went potty, absolutely potty,” Altham remembered. “Jimi was waving the guitar around his head. [The security guard] came onstage with a fire extinguisher, somehow the compere (Nick Jones) got in the way and he got fire extinguished - he got all these chemicals in his eyes. He put out the guitar and Jimi at that point had left the stage.”

“You’ll never work in this theater again!” shouted the enraged security guard (who, amusingly, went by the name of Tito Burns) at the fleeing Hendrix.

By now though, the crowd were wide-eyed at the sheer unbridled chaos that Hendrix had unleashed.

Jimi Hendrix was not someone they'd forget in a hurry.

As Polydor's George McManus remembered, "The feeling in the audience was more shock than fear. We'd been watching this man playing wonderful music, and now he'd set his guitar on fire. What was that all about? We were literally gobsmacked."

Word would, naturally, spread of what the crowds and journalists had witnessed that night at Finsbury Park. Hendrix and Chandler had created their story, and the first domino had fallen.

By the year’s end, Hendrix was a pop culture icon.

He'd go on, of course, to inspire subsequent generations to come via both his technical brilliance and his breathtaking performances.

Sadly, he’d die in September 18th 1970 of an unintentional sleeping pill overdose at the all too young age of 27.

“I’m not sure I will live to be 28 years old, but then again, so many beautiful things have happened to me in the last three years. The world owes me nothing,” Hendrix was quoted a saying in the book Starting at Zero: His Own Story.

Jimi’s ritual guitar burning would only actually take place a further three times, but due to the iconic footage captured at the Monterey Festival, it’s become widely assumed to be have been a staple of Hendrix’s live set, with only a few people knowing that this only occasional act was first triggered by a journalist’s quip.

“I felt like we were turning the whole world on to this new thing, the best, most lovely new thing,” Hendrix was quoted as saying in Starting at Zero. “So I decided to destroy my guitar at the end of the song as a sacrifice. You sacrifice things you love. I love my guitar."

Years later, the original Fender Stratocaster that Hendrix torched that night in March 1967 was sold at auction for £280,000 to collector Daniel Boucher from Boston, Massachusetts. "It was something I wanted to have," he told the BBC after picking up the still-singed axed. "I decided I would go the distance to get it."

For Altham, his career would continue to intertwine with Jimi’s, remaining close to the guitar giant until Hendrix's untimely death three years later.

In fact, Altham was the journalist for whom Jimi sat down with for his final interview.

“Jimi was not eternally grateful [for coming up with the guitar-burning] I have to say,” Altham recalled. “[Before] he went on at Monterey he said to me, ‘I’ve got a good idea, why don’t you set fire to your typewriter.’”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores the inner-workings of how music is made and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for a range of titles including NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.