“There’s a freedom of thought that doesn’t exist elsewhere”: How and why California became the heart of the synthesizer world

Many of the biggest players in the genesis of modern music-making hailed from California, but just what made the state such fertile ground for the synth pioneers to flourish?

California has been - and remains - home to a surprisingly large number of synthesizer companies, from Buchla to Oberheim to Sequential and many more. But why is the Golden State so verdant with technological innovators?

Here’s the story of how California turned into a synth Mecca - and why so many of its major players ended up working together.

When we think of where synthesizers come from geographically, we tend to think of countries: the big, brash sounds of American Moogs, and then there’s the polite and versatile Japanese Rolands.

Look closer at the countries, though, and you’ll find the companies are spread out all over the map. Synth engineers live all over; they tend to set up shop where they are.

California is different though.

The American state is home to a staggeringly large number of companies, a roll call that includes such luminaries as Buchla, Oberheim and Sequential. And that’s just scratching the surface.

Dig a little deeper into the history of California synthesizers and you’ll find not only a wealth of companies but important connections to some of the state’s other major industries, technology and entertainment, as well as a unique spirit of collaboration achieving a real-world synthesis that mirrored what was happening musically.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

California in the 1960s was a wild and fertile place. Although you could argue that the California technological revolution started in 1939 with the establishment of Hewlett-Packard in a garage in Palo Alto - part of what would come to be called Silicon Valley - it was the 1960s when things really started to happen, both technologically and, yes, chemically.

Stanford University was the home of bleeding edge experiments in computer science, artificial intelligence, and digital synthesis thanks to John Chowning’s work with frequency modulation.

Although you may think of engineers as being buttoned-down and straight-laced, the book What the Dormouse Said by John Markoff paints a different picture, one of psychedelic awakenings happening concurrently with technological ones.

“His idea is that the San Francisco ‘60s utopian counterculture, psychedelic drugs, defying authority, breaking rules, and a general sense of severing from the past for a brighter future all led to an explosion of new ideas,” says California native and instrument luminary Roger Linn.

Another place where psychedelics and the counter culture were building up steam was in San Francisco, just up the road from Palo Alto.

It was here, specifically at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, that the seed for the Buchla 100 modular was born out of a need for a new kind of instrument that could allow a single musician to create full compositions on their own.

Don Buchla was in the right place at the right time to make that instrument for the Tape Music Center, and his revolutionary circuits would go on to inspire countless other musicians, not to mention soundtracking some of Ken Kesey’s ‘Acid Test’ parties.

Don would remain at the forefront of synthesizer design for his entire life, particularly pioneering alternative control systems such as touch-sensitive keyboards and even collaborating with Moog on the Piano Bar, a non-invasive device that turned any piano into a MIDI controller.

Another engineer to benefit from Don’s brilliance was Serge Tcherepnin. A European transplant, Serge made the move to California to teach at the California Institute of the Arts in the early 1970s. Also known as CalArts, this was to be the headquarters for Serge’s own modular experiments, many of which were inspired by Don’s open source circuit designs, an unusual business choice but one in keeping with the counter-culture spirit, and certainly one encouraging collaboration.

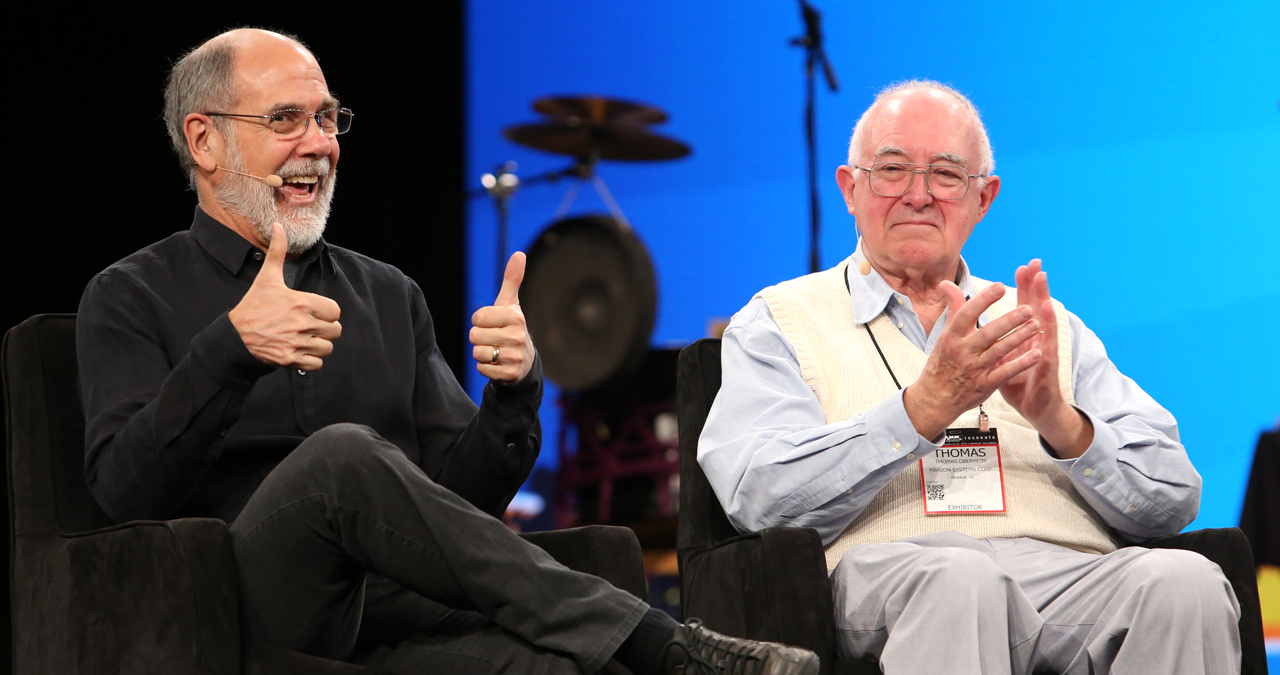

In 1956, a 20-year-old from Kansas named Tom Oberheim moved to Los Angeles to be closer to the jazz music that he loved. While taking classes at the University of California, Los Angeles, he befriended a number of musicians and began making effects units for them. This started him designing circuits for pedal company Maestro and eventually his own synth, the ‘Synthesizer Expander Module’, also known as the SEM.

Being the center of the entertainment industry, Los Angeles was a great place to headquarter a synthesizer company - especially when your products were as good as Oberheim’s.

“The Northern Californians got the benefit of proximity to technology, while us Southern Californians had the benefit of proximity to artists and the L.A. session scene,” says Marcus Ryle, who would join Oberheim in the ‘80s and spearhead development of the Xpander and Matrix-12. “Sometimes the synths got used on records before they even shipped.”

Artists who used Oberheim synths are legion, including Prince, Van Halen and Rush, as well as Joe Zawinul of Weather Report, who benefitted from a personal lesson from Tom at his home in Los Angeles on how to program his new 8-Voice, a session that ended up yielding the signature sound on Birdland.

Oberheim also benefitted from collaboration with engineers from outside the company. Tom was already friendly with ARP, having been the company’s sales representative for the Los Angeles area, and so was able to tap Dennis Colin to design the state variable filter for the SEM.

“Those of us in the business are friends with East Coast folks, British folks, on and on,” explains Tom. “That's what is great about our business.”

Another engineer who lent a hand with the SEM was E-mu’s Dave Rossum, who not only worked on the expander unit’s oscillator, he designed the digital polyphonic keybed that allowed Oberheim’s 4-Voice to be the first polyphonic synthesizer in shops - as well as the one for the Prophet-5.

Dave Rossum is something of an unsung hero in the history of synths, his name not nearly as widely recognised as that of some of his contemporaries. He’s known for his work at E-mu Systems, most notably the Emulator series and SP-1200 sampling drum machine, but his contributions go not only deeper but also, crucially, wider, with his work on the Oberheim SEM just one example of his work outside of E-mu.

A native of the San Francisco Bay Area, Dave caught the synthesizer bug while studying graduate-level molecular biology of the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1970.

Invited to unpack a new Moog Model 10 for the music department, he soon found himself studying its schematics and, eventually, starting E-mu Systems with a number of friends, chiefly Scott Wedge, who would go on to play a major part in the company. Their first product was the E-mu Modular System, with customers including Frank Zappa, Hans Zimmer and Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Hideki Matsutake.

Here was where Dave’s influence began to expand. Dave was a prolific circuit designer, and many of these ended up as chips for California’s Solid State Music Technology. Better known as SSM, the company emerged out of Silicon Valley’s Homebrew Computer Club, which also counted Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak as members.

Some of Dave’s chip designs included the SSM2040 VCF, 2020 VCA, and 2030 VCO. Not coincidentally, all three of these are in the first revision of the Sequential Prophet-5.

Dave and Scott designed a polyphonic keyboard for the E-mu Modular that could play up to four notes. Called the E-mu 4050 Modular Keyboard, it was also licensed to Oberheim for the 4-Voice. “What made our polyphonic keyboard unique was that we chose to make the logic so that rather than assign voices by lowest and highest note, we assigned them by first played, second played, etc.,” Dave told Amazona.de.

“We were the first to market with a solution that actually worked.”

The follow-up to the 4050 was the 4060 Microprocessor Keyboard. Again designed for the E-mu Modular System, it supported up to 16 voices and included a polyphonic sequencer. It would also be licensed, this time by another California engineer, Dave Smith.

There are so many smart people here in Northern California, and there’s a freedom of thought that doesn’t exist elsewhere,” says Roger Linn, a Southern California native who moved north later in his career. “There’s a wave of intellectual momentum that is both rare and a pleasure to surf on.”

The San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s was a hotbed of technological innovations. The two Steves were famously developing the first Macintosh computer in a garage, but not too far away another fledgling company was working on a different technological revolution.

Dave Smith founded Sequential Circuits in 1974 and, along with a handful of SSM chips, the keyboard licensed from E-mu, and a Z80 processor, he and John Bowen were able to create a first: a polyphonic analogue synth with patch memory. Called the Prophet-5, the programmable poly beat many established companies to market and became the synth to have in the late 1970s.

Of all of the California synthesizer companies, Sequential is probably the most representative - and long-lasting, having come back officially in 2015 when Yamaha, who had bought the company in 1987, returned the name to Dave as a goodwill gesture.

Among many of its releases was 2016’s OB-6, the first pairing up of Sequential and Oberheim. That collaboration, which Tom says is a ‘one of a kind’ thing, continued with 2022’s OB-X8, the same year that Oberheim was officially revived under its original name.

Tom, for his part, doesn’t agree that California synthesizer companies are so different from those in other parts of the world. “For the most part, collaboration has been rare,” he insists, likely referring to the kind of deep partnership he achieved with Sequential. Taiho Yamada, the Head of Marketing at Sequential and Oberheim, believes instead that the real force of collaboration in the state was Dave himself.

“Unfortunately, we can't ask for his take directly,” Taiho says, “but I think Dave Smith was the common denominator in some standout collaborations. Beyond the revival of Oberheim that he worked on with Tom, there was his relationship with Ikutaro Kakehashi of Roland that spawned MIDI and earned them a joint Grammy. And we'd be remiss not to mention Dave's collaboration with Roger Linn on the Tempest drum machine.”

Released in 2011 under the Dave Smith Instruments brand, the Tempest drum machine was a true collaboration between Dave and Roger Linn, who had developed the LM-1 (with a little help from Dave Rossum!), LinnDrum and Akai MPC60, among other instruments.

When asked how that collaboration came about, Roger casually explains, “Dave and I were hanging out and it was something like, ‘Roger is the drum machine guy and Dave is the synth guy, so let’s make a drum synth together.’” So very California.

Roger sums up the spirit of California collaborations like this: “When I and the other people were starting out, we weren’t business people but rather people with a strong passion about what we viewed as the magical intersection of music and technology. There weren’t many of us, so it wasn’t long before we all met each other, which eventually led to collaborations. What’s better than meeting people who share your passion?”

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.