“A synthesizer enhances worship. When we use the synthesizer, we sing even more enthusiastically”: Exploring the link between spirituality and synthesizers

Why has the synth has become a key navigational aid for those seeking deeper truths?

From Alice Coltrane’s devotional music to modern ambient interpretations of Sufi mysticism, synthesizers are everywhere in spiritual music. But what is it that makes synthesizers so attractive to those inclined towards the deeper mysteries? We spoke to four artists about their personal, transcendent relationships with synths.

In the early 1980s, jazz musician Alice Coltrane started incorporating the Oberheim OB-8 into her bhajans - traditional Hindu devotional songs performed at her ashram.

Best known for playing the harp, Coltrane - who was famously something of a luddite - embraced the OB-8 after her daughter Michelle recommended she check out modern synthesizers. “I said, Mom, you gotta check out Roland and Korg and all these products that are coming out,” Michelle said in an article in the Guardian. “The next thing you know, we’re on that Oberheim.”

You can hear the big analog poly all over the music on World Spirituality Classics 1: The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda, a compilation collected from self-released cassettes from her ashram era.

Full of lush chords and swooping, rising portamento, it’s a potent and often surprising accompaniment to the joyful group singing. While you might not expect synthesizer in such a religious context, in practice it makes perfect sense. Both musically and, dare we say it, spiritually.

In the four decades since Coltrane electrified her bhajans, the synthesizer has come to be accepted around the world as an acceptable element in devotional music of many kinds.

It’s common in Christian church worship sessions (“A synthesizer enhances worship. When we use the synthesizer, we sing even more enthusiastically,” said an article called 'Praising God with a Synthesizer' in 1987), in nondenominational ambient/New Age epics, and in pretty much any other type of spiritual music you can imagine.

But why? What makes a synthesizer such a spiritual instrument? Four artists from different places around the world, and with different spiritual leanings, all attempted to get to grips with this question.

“Sound is a wave”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“For me, synthesizers are deeply spiritual because they resonate with my Sufi practice,” explains Dr Kamal Sabran, a musician and teacher in Malaysia who releases music under the name, Space Gambus Experiment. “In Sufism, sound is not merely vibration; it is a carrier of presence, a mirror of the unseen. Life begins with sound, the divine command ‘Kun’ (Be). Everything that exists is an echo of that original vibration.”

Dr Sabran uses his synthesizers to create vibrations that “speak directly to the body and the soul.” It’s clear that, to him, the entire process is profound and deeply spiritual. “When I engage with a synthesizer, I’m not composing in the traditional sense. I approach it as a form of tafakur, a meditation through sound. The synthesizer allows me to sculpt subtle shifts, drones, and textures that bypass the intellect and touch the soul directly.”

Marqido, the Japanese musician handling synthesizers for the pan-Asian family band Tengger, also points to sound as a fundamental spiritual aspect of synthesizers. “As you learn about synthesizers, you encounter philosophical questions such as, ‘What is sound?’” he says. “Sound is a wave, so it affects the mind and body of the listener. Waveforms are invisible to the eye, but the sound exists. I think the sound creation of synthesizers is truly mysterious.”

For Jeremy Arndt, who blends mindfulness-based practices of yoga and meditation with his music, synthesizers represent a personal escape into an inner world. “I believe any musical instrument can be spiritual if it takes the player on an inward journey,” he opines. “For me, synthesizers offer a unique personal experience when I'm playing them.” Although his primary instrument is the handpan, an acoustic instrument, he stresses that he has a deep passion for synths. “I oftentimes feel like creating a new patch or playing the synth is giving my body, mind, and spirit its own personal tune up.

“Electronic sounds can expand the imagination”

Shinto, the native religion of Japan, focuses on nature and imbibes everything in the world, living or inanimate, with a spirit. For Tengger, synthesizers are a way to represent this in their music. “Regardless of whether they are analog, digital, or plugin synthesizers,” he says, “we used them all in the same way, with a preference for repetitive and simple methods. This is because we use them to express the simple essence of nature and the dynamism of the universe.” Summing up, he adds, “Electronic sounds can expand the imagination. I think it is the perfect instrument for expressing the invisible world.”

The sound of the synthesizer is important to Dr. Sabran as well, who identifies them as being unique amongst the world’s instruments because they grant the user access to sound in its purest and most elemental form. “In Sufism,” he explains, “there is an emphasis on the unseen (ghayb), on subtle realms beyond the material. Synthesizers, especially analog ones, allow us to sculpt these unseen energies directly.”

And because they can generate sound from nothing, he adds, “they reflect the Sufi concept that everything comes from One Source and returns to it. The synthesizer’s ability to sustain, to evolve infinitely, becomes a metaphor for the soul’s journey back to the Beloved.

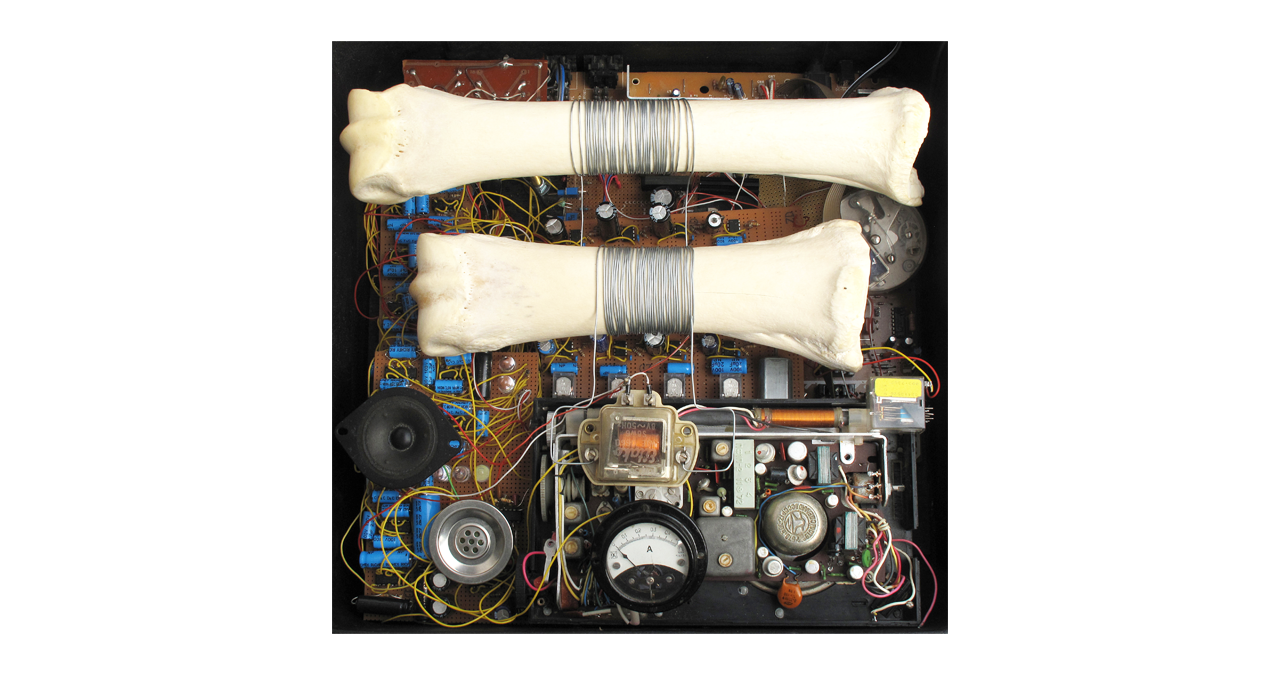

Guido Henneböhl, a Berlin-based artist and musician who records under the name Mondo Skull and creates all of his own instruments (“A lot of the building is like meditation: I usually don’t draw my circuits beforehand, but rather solder my ideas directly to the board, which requires a maximum amount of concentration”), sees synthesizers as more spiritual than other instruments because of the conscious decisions made by the synth’s designer. “A violin, for example,” he says, “is, at its core, only a piece of wood with strings. It takes years and years of hard work and practice to reach the point at which a player can produce a deep spiritual experience with the instrument.” With a synthesizer, however, “the designer … has already done a good part of the spiritual work, has thought through the various sonic possibilities of the instrument, and has made these sonic possibilities easily accessible to the player.”

Dr Sabran sums up the difference: “Other instruments are like rivers; they carry deep emotion, tradition, lineage. But the synthesizer is like the wind: invisible, ever-changing, untethered. It invites you to trust, to surrender, to listen inwardly. That is its spirituality.”

“Electricity and magnetism are fundamental forces in the universe”

Another area in which the synthesizer can be seen as particularly spiritual is in its use of electricity. Many instruments are electric; synthesizers allow one to create sound with electricity itself.

“I think electricity and magnetism are fundamental forces in the universe,” says Henneböhl. “It’s all about energy, load, polarity, oscillation, and so on. These are very basic concepts, but ones that can teach you a lot about music, aesthetics, and spirituality when you dive deeper into them.”

“I don't really know of any other instruments that allow you to create with electricity the way a synth does,” agrees Arndt. “To take an electrical signal, that we typically take for granted in our daily modern lives, and be able to pass this signal through oscillators, VCAs, envelopes, filters, etc., and shape them to your creative will, is something that I find very fascinating."

“The synthesizer becomes an extension of inner life”

Another way that artists can channel the spiritual through their synthesizers is by making or modifying their own. While the building of most traditional instruments can require years of dedicated practice and effort just to attempt, the electronic nature of synths means that anyone with a soldering iron can at least modify them. “There’s a kind of intimacy in that process, making something imperfect, unstable, and alive,” says Dr Sabran, who often builds his own instruments through circuit bending and modifying old electronics.

Dr Sabran quotes from Hazrat Inayat Khan, a Sufi musician and teacher, to illustrate his point: “The more one becomes acquainted with the inner life, the more one sees that all is music.” The synthesizer, says Dr Sabran, “especially when you’ve built or bent it yourself, becomes an extension of that inner life.”

Henneböhl, who builds his own instruments – often in a trance-like state – likens playing his self-built creations to discovering a new world, one that he couldn’t imagine during the building process. “It’s a bit like a fascinating journey where the machine itself is carrying me to places and experiences that I can explore and then present to the listener.”

“The sound takes on a life of its own”

When asked if they had ever had a profound spiritual experience when playing a synthesizer, everyone answered in the affirmative; and almost everyone highlighted a feeling of being transported beyond the self.

“When playing improvisationally,” says Marqido of Tengger, “there are times when I feel as if my fingers are being moved by something. The more unconscious I become (of what I’m doing), the more I feel this way. Intuitive playing connects me to something greater than rational playing.”

Jeremy Arndt mentioned a similar experience when working on one of his recent albums, Distant Vistas. “It was a quite profound time of deep sonic meditation for me,” he remembers, “and to this day I've not been able to recreate some of the handpan music that came forth during that period, which was inspired by layers of synthesizer exploration. It was there for a fleeting moment, captured, and gone forever.”

Dr Kamal Sabran has also had many many deep spiritual experiences while playing the synthesizer, especially when using self-oscillating patches. “In those moments, it feels as though the sound takes on a life of its own, beyond my control,” he explains. “The frequencies begin to evolve infinitely, shifting and morphing in ways I did not plan. This unpredictability becomes a spiritual lesson, a reflection of tawakkul, the Sufi concept of surrendering to the Divine will.”

He continues: “In those self-generating, feedback-rich sonic environments, especially with analog synths, I’m reminded that I cannot control the journey. I can only participate, surrender, and listen deeply. That is where the Divine whispers.”

Sound is spiritual

Ultimately, the sound of the synthesizer itself can be deeply spiritual. “Though it may sound contradictory,” said the article advocating for synthesizers in worship music in 1987, “there is nothing more stirring, uplifting, and human than a pair of analog oscillators producing a warm, lush string sound.”

“It happens a lot that I suddenly discover a sound that touches me in a deep way that could well be called spiritual,” says Guido Henneböhl. “Even a simple sine wave for example, or two of them running against each other, can create a strong spiritual experience – if you know how to listen.”

Marqido has also found the sacred in sine waves. Although some of the musicians quoted in this piece noted analog as being particularly spiritual, Marqido instead leans towards FM synthesis. As with Shinto, which recognizes the spirit in everything, Tengger finds it even in a Yamaha DX7.

“The DX7 is truly an enlightening synthesizer,” Marqido enthuses. “The theory behind it, that all sounds in this world can be broken down into sine waves, and all sounds can be created by combining sine waves, is very cool and, above all, spiritual. I often find myself consciously listening to sounds, realizing that even the sounds I hear casually every day contain various overtones.”

The Sufi poet Rumi said, “Try to be like the nightingale who sings regardless of who listens.” For Dr Sabran, this often comes true when working with synthesizers. “The sound is not mine,” he says, “it is a gift moving through me. Hazrat Inayat Khan spoke beautifully about this, saying that ‘music is the language of the soul, the bridge between the form and the formless.’ I deeply believe that."

Adam Douglas is a writer and musician based out of Japan. He has been writing about music production off and on for more than 20 years. In his free time (of which he has little) he can usually be found shopping for deals on vintage synths.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.