“I’ve never fully gelled with Logic and Pro Tools – they kind of feel like Microsoft Excel to me”: Jacques Greene and Nosaj Thing on the making of their new collaborative project, Verses GT

As two mainstays of modern electronica unite as Verses GT, we hear about the Sequential synths, $20 plugins and Eurorack gems behind their debut full-length project

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Two mainstays of modern electronic music, Philippe Aubin-Dionne and Jason Chung – better known as Jacques Greene and Nosaj Thing – have each charted a distinct creative course over the past two decades.

Aubin-Dionne is a Montreal-born producer/DJ that writes sleek and evocative dance music that pulls as much from R&B as it does UKG, its restless rhythms tempered by yearning vocal cuts and warm, expansive chords. While his music is kinetic enough to move a dancefloor, its structures often venture beyond the boundaries of the club; in Aubin-Dionne’s words, these are songs, not tracks.

Chung’s music is slower and more spacious, emerging out of the fabled L.A. beat scene in the late ‘00s, a community of producers, DJs and musicians aligning leftfield sound design with head-nodding hip-hop beats. His cerebral glitch-hop has since morphed into a singular strain of minimal electronica, and recent releases have called on a varied cast of collaborators that includes Toro y Moi, Coby Sey and Panda Bear.

Meeting early on in their career, Chung and Aubin-Dionne spent a decade throwing around ideas whenever they happened to land in the same city, but it wasn’t until 2023’s Too Close that they realized they’d touched on something that transcended their solo outputs, becoming more than just a marriage of two styles. Uniting under the name Verses GT, they embarked on a B2B DJ tour while working on the material that would become their self-titled debut, testing ideas in the club before fleshing them out in spontaneous Ableton jams in rented studios.

The result is a ten-song project that lives in the moody, nocturnal space where the duo's Venn diagram overlaps, a synthesis of styles that’s far more than the sum of its parts. Drawing on their shared gift for building atmosphere and tension through dextrous sound design, it’s an absorbing listen, rising and falling through ethereal ambience, ghostly textures and quavering Prophet pads.

Aubin-Dionne tells us they were trying to capture the vibe of "driving alone at night", and it shows. The album sustains a dusky, sombre tone while touching on multiple reference points: Intention is woozy deep house, Forever channels dubstep rhythms and the reverb-streaked UKG of Unknown and Your Light is a testament to Burial’s enduring influence. Though it’s spare and subtle, there’s sensuality here too, and vocal turns from George Riley, TYSON and KUČKA lend a sense of warmth and humanity to Verses GT's jittery, skeletal beats.

We caught up with Jacques Greene and Nosaj Thing to find out more about the making of Verses GT.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Could you both take me back to your first experiences with electronic music-making?

NT: “I have two memories. I remember visiting a family friend’s house when I was a teenager and he had a Roland JX-305 – I guess that’s kind of like a synth version of the MC-505 groovebox. He was using it to make covers of big trance songs, and I was just blown away, but also kind of heartbroken, because it was too expensive. We couldn’t afford anything like that.

“Freshman year of high school, I had some older friends that got me into DJing and scratching. When I was in ninth grade, I ran into a friend, and he was like: ‘yo, meet me here tomorrow in between classes’. Of course, I met him there, and he gave me a burned CD of Reason and FL Studio. I installed it on my computer and that was it, that was a wrap for me. I was on it every day.”

"I got a cracked copy of FruityLoops, then worked all summer in a shitty bakery so I could buy an MPC1000 on Craigslist"

“I was also in drumline in high school, so I was using that to create drum cadences and stuff. At the same time, I was obsessed with The Neptunes and Timbaland, so I was recreating Neptunes beats. The production in the early 2000s resonated with me because I could understand it. You could go to a Guitar Center and use the keyboards that they were using, like a Triton or a Motif or something. I was like, ‘oh damn, they’re just creating all of these sounds and writing it themselves.’”

JG: “Timbaland and The Neptunes are weirdly also my entry point too. You’re 13 years old, and the fact that they were in the videos and communicating in a very mainstream way that they were the ones making the beats, to me was like… ‘oh, without being the vocalist, there’s room in this kind of music to be a bit of a nerd’. That was a real inspiring window into a role that I didn’t know existed. There was something about how they were presenting themselves that I just understood. Like, you can actually just make beats.

“That was definitely a viewpoint into electronic music for me. Around the same time, I had a very young high school teacher, and I had a bit of a School of Rock moment where he gave me a stack of CDs to take home. There was Autechre, Squarepusher, Boards of Canada, Amon Tobin and Aphex Twin… that was a real jump in at the deep end. I never wanted to play in a rock band ever again after that. I got a cracked copy of FruityLoops, then worked all summer in a shitty bakery so I could buy an MPC1000 on Craigslist.”

When did you both meet?

JG: “We met roughly 15 years ago. I was 18 or 19, and a mentor of mine that makes music as Sixtoo was putting on a monthly party where he was booking Low End Theory-associated, experimental instrumental hip-hop stuff. He brought Jason to play in Montreal. We only started making music a decade after that, and even then it was very loose - whenever I’d be in LA, we’d make a couple tracks.”

When did you decide to join up under a new name and work on a full-length project?

JG: “Two years ago, roughly. We would meet up whenever I was in town and make some music, but then we had this first track that really connected for us personally, Too Close. Both the way that it was made, and just the feeling of it was just like… ‘damn, this is kind of cool’. That one feels more like a real blend of two of our approaches, but a lot of the work that ended up on this album feels like a third completely different thing. In a way, that was more exciting than a fusion.

“Two years ago, we had a moment where we're like, ‘okay, not only do we have a lot of stuff that we both are pretty excited about, but it all feels like it would never fit on my own record, and it would never fit on a Nosaj Thing record’. This is really its own thing. So at that point, we had quite a lot of demos, but we also had a defined sandbox of what this project was and what it wasn’t. Then we could then begin to work towards something where we knew where we were going.”

What were the limitations of that sandbox?

JG: “Part of it was in the arrangement and the process of reduction. Letting our instruments take up space, reducing layers, it was a headspace thing. Also it was some of my kit, some of his, depending on where we were recording. The Prophet-5 takes up a lot of space on the album, and we ended up really honing in on one reverb that gave a sense of space to the whole record. Part of it was definitely subconscious; we didn’t sit down with a notepad. We just looked back at this stuff and said, the sound of our record is drums that kind of feel like this, it’s sections that feel loopy and heady... It’s like driving alone at night.”

NT: “Even after Too Close came out, when we first decided to get out there and do some B2B sets together, those experiences really helped to inform our sound. A couple of the singles that came out, testing them in the venue and then having conversations the next day or at the airport about what worked and what didn’t work, that really helped us shape the sound as well.”

Tell us about your collaborative process as a duo. How does that play out in the studio?

JG: “We almost surprised ourselves by switching roles. People that have followed both of our music for a long time would maybe be surprised to find out that on a lot of the songs Jason was the one cutting up a vocal, for instance. We traded roles a lot.

“One of the very important ways this record came together was through Ableton Link. In Ableton Live, if you're on the same network, two computers running Live can be perfectly synced, and we could have both of them running through the speakers. So there was this real jamming element. Pretty much every single song was started in the room together – after that we could argue over a snare sound months later over shared files, but everything was started in the same room, and we’d just have both laptops running.

“To be honest, I'd say the most exciting tracks to us were literally wordless. We'd start working, stop talking to each other and enter this weird trance-like state. One way that really differs from when you're making music alone is that you can only do one thing at once.

“On the track Unknown, for instance; we're working at Nosaj’s studio in LA and he goes over his Prophet-5 and he’s playing a few different melodies. But while he's doing that, I'm responding, I'm over at the arrangement, being like, ‘okay, if he's playing this kind of thing, maybe we can remove the shaker’. There's this real call-and-response going on as multiple things are happening at once.”

The press release mentions the album was recorded across a number of different locations?

JG: “Yeah, we booked a couple places. Part of it was because we were on this extensive back-to-back DJ tour last fall. We were very much in the midst of finishing a lot of this music, and we were testing out our own songs at night and being like, ‘maybe we should edit this little thing, or maybe this part should be a little longer’. Playing tracks out, you can really get direct feedback and see how they occupy space.

“One moment we both remember fondly: we were DJing in Leeds and we reached this part of the set where we’re playing this very hazy, moody deep house. I turn to Jason and I’m like, ‘the way the room feels right now, remember this. We need a track that feels like this.’ Not even going back to the particular songs we were playing, but just trying to make a note of how the dancers are responding and how thick the air felt in the moment.

“The next day, we’re on the train back to London, and we’re asking around for studios we can book for the day. That’s when we wrote Intention, one of the tracks on the album, with the title being a reference to entering the studio with an intention. That was one of those where it’s like, 55 minutes after entering the studio, the bedrock of the track is done, because we had such a particular idea of what we wanted.”

Could you talk us through one or two instruments or pieces of gear that were fundamental to the making of the new project?

JG: “The Prophet-5 definitely feels instrumental in that it has so much character that you can really let it do its thing. A lot of the stuff that we are gravitating towards are things that carry a lot of their own personality, in the way that you don’t feel you need to drench it in 1000 different effects. Once you dial in exactly what you want from it, you can really let it breathe.

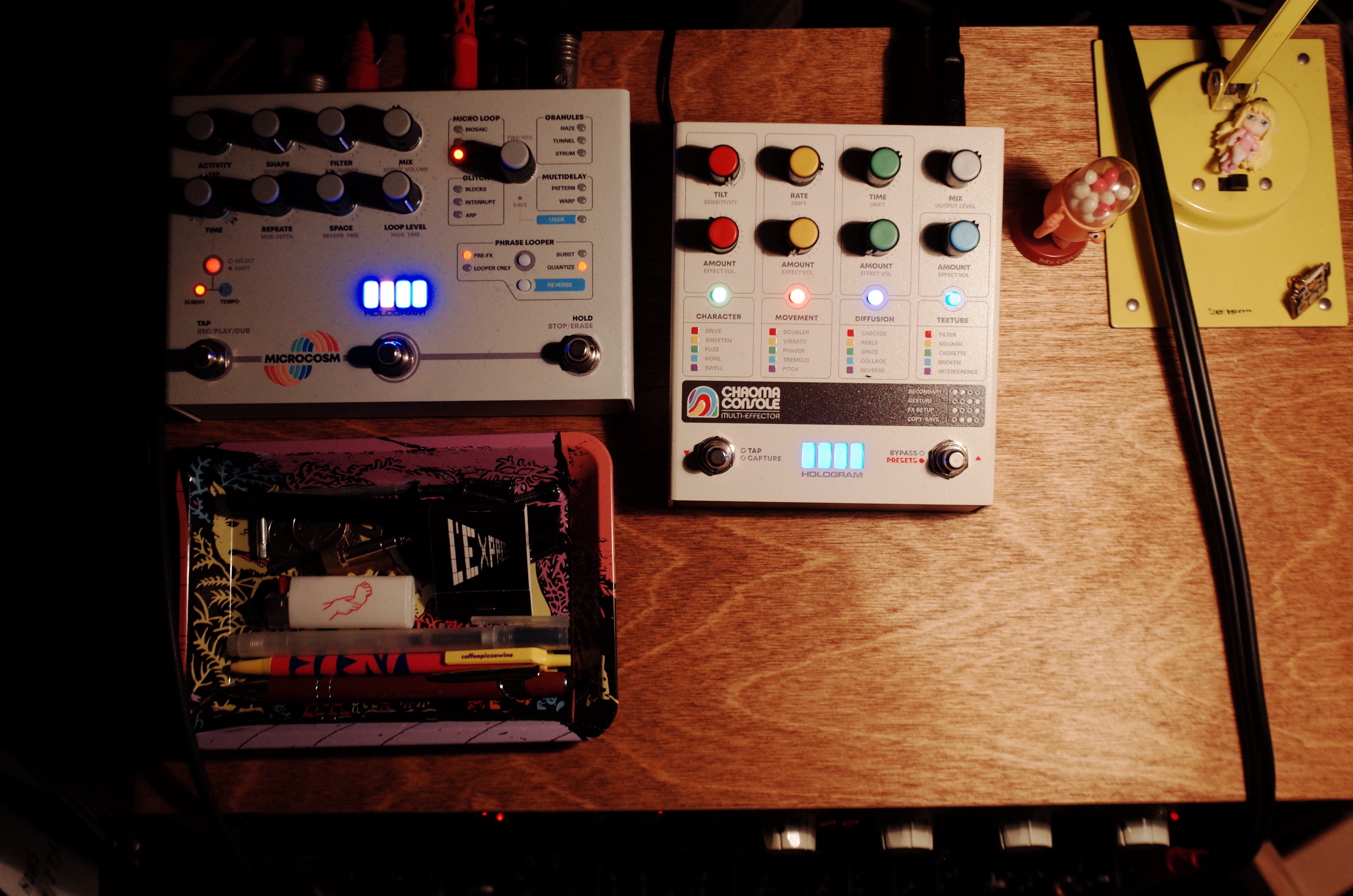

“The Prophet-5 is a good example of that, and the Erica Synths Perkons drum machine is another example. I go to my Chroma Console effects pedal a lot. I like pedals as a way to bounce out extremely digital stuff you've done, like MIDI drums or whatever, and then send that top end percussion through it, just to spice it up a little bit.”

NT: “Definitely Erica Synths, Intellijel, Instruo. They make amazing modular pieces. Our setup was pretty minimal. We don’t have tons of gear.”

JG: “But everything is good. It’s the way I want a restaurant or a fashion design to be. I don’t want a jacket with 100,000 zippers and patent leather, I just want a well-cut simple jacket. The studio set-up reflects that approach; it’s not about having a thousand different things happening at once. It’s a perfectly dialled pad sound, or the perfect little scratchy hi-hat.

"I had a realization during Covid and sold all my gear that requires menu-diving"

“After that, though, you still obsess over those things. We worked at Motorbass in Paris, which was a really special day for us, and there’s some crazy stuff there that we had a chance to work with – there’s a Yamaha CS-70 on the record. The guy’s got a wall of Pultecs and really nice compressors, and we’re like ‘this one snare, how do we make it really pop?’ Just sitting down with him and making sure that we really fine-tune the few things that are there.”

NT: “Software is so good now, as well. We used a lot of Arturia stuff, there’s a lot of Pigments across the record. I had a realization during Covid and sold all my gear that requires menu-diving. Every piece of hardware I have now is immediate, and it’s mostly analogue equipment.”

JG: “That’s where the Erica Synths stuff comes in, it’s so fun to use. Whenever I see a video of Erica Synths gear, they’re making noisy slam techno. [laughs] It’s fun to repurpose gear into another genre. Even when it comes to sample packs, it’s cool to make techno using UK drill drums, for instance – it’s cool to take something and bring it somewhere else. To me, having the Perkons do a really small, elegant percussion pass where you’re only using a certain section of the drum machine, is where some of that gear becomes exciting, when it can still surprise you.”

You mentioned you’re both using Ableton. At what point in your career did you switch to Ableton? Why does it work for you?

NT: “I’ve used Ableton since 1.0, which is kind of crazy. You got a free copy of Ableton Lite with the M-Audio Trigger Finger Pro. That was before it was even a full-on DAW, it was almost like ReCycle, just for chopping and stretching loops. I’ve been using it since then and slowly transitioned from Logic to Ableton.”

JG: “It was Ableton 4 for me, in 2004, which is insane. In FL Studio, the design feels like you're playing a PlayStation music-making video game. It’s fun when you're like, 13 or 14, getting into it. And that’s not to say that people that use it as adults are childish, that's not what I'm saying at all. But I think for me, there was something about Ableton that in its look and feel and use has always been that perfect blend of serious-feeling but extremely playful.

"There were a few of these funny little one-trick-pony plugins that you pick up for $20 in a plugin sale, but they end up giving a huge amount of personality to something"

“I've never fully gelled with Logic and Pro Tools, they kind of feel like Microsoft Excel to me. [laughs] I don't feel a sense of play when I'm using them. Ableton has managed to get so good with time, the built-in stuff is just unbelievable. But there's still that genius of switching between the Session and Arrangement views. Really early on in making electronic music, I was playing live, and the fact that my projects could be ported from the studio to live extremely easily in the same kind of architecture was always really appealing to me.”

Phil, you’ve spoken before about how much you love your $40 Alesis 3630 compressor, saying that it’s often the “the tools of the people” and “the pieces of shit” that have the most character. Did you use anything on this record that falls into that category?

JG: “That’s a good question. There’s no 3630 on this record, which is too bad. In the last few years I’ve become slightly obsessed with an early Access Virus, the Virus B. A lot of the supersaw basslines on this record, that’s the Virus. In a way, to me that’s a bit of a tool of the people, because there’s not that many polysynths under $900 anymore. [laughs]

“What else? Jason, you showed me this one: Cableguys HalfTime. There were a few of these funny little one-trick-pony plugins that you pick up for $20 in some kind of plugin sale, but they end up unlocking a very strange texture or giving a huge amount of personality to something.”

Something I really liked about the record is the use of subtle textural elements to bring atmosphere to the music, like on Left. Can you tell us about how you create those kinds of sounds?

NT: “A lot of times I just cranked up the preamps and allowed the natural noise of the drum machines and synths to come to life, and we’d just leave it in.”

JG: “We obviously love heavy texture in music, from Madlib to Burial – two good reference points to this record – but we’re not sampling vinyl here, and it would be disingenuous and maybe a little boring to have vinyl crackle on the record for no reason. We were using some stuff that had genuine ground noise and surface noise, and instead of hiding it, within reason, we’re allowing that to enter the recording.

“Sometimes the pots are a little scratchy on a module, for example, and the Erica Synths stuff is super noisy. A lot of the fuzz on Unknown is letting a lot of that ground noise live in the track, and it gives an interesting sense of space and character to everything.”

Did you experiment with any new techniques on this record? Did you learn anything new?

NT: “Just from working with Phil, and seeing how he approaches arrangement, I learned a lot. That’s what I learned the most, arranging new ideas and thinking about what arrangement can be.”

JG: “What’s fun about it, and what felt so fresh to me is that the only reason a lot of these songs could end up the way they are is because they were made in person with someone else. When I’m alone, I end up with completely different results.

“My instinct has always leaned towards stacking different melodies or counter-rhythms, and sometimes there’s maybe one too many layers. But with Jason, there was more of trusting that this one element is enough to hold someone’s attention. Adding something else won’t augment this feeling or this groove or emotion, it’s actually going to detract and confuse your brain. It was an exercise in reduction and focus that I’ve never quite been able to get to on my own.”

I suppose when you’re working collaboratively, you become accountable to someone else. That’s an entirely different headspace – it’s not just about you any more.

JG: “Yeah. Another thing that was really cool – as we started finishing some tracks remotely was, sometimes we’d send each other an idea, and it’d be something that maybe I would do that Jason would never do, or vice versa. But then I’d catch myself and think, ‘it’s cool if part of this song is a Nosaj creative decision and not my way. It’s cool if there’s a push and pull’.

“It was about allowing that feeling of like, ‘yeah, I would never do that’, in a way that would at first make me uncomfortable, but then I’d sit with it for a couple days before I even reply – because in the end, maybe it’s more interesting, and it broadens the scope of the creative decisions that are made on the record.”

NT: “I agree. That’s the fun of it, you know what I mean? Especially for what we do, as solo electronic producers or beatmakers in our own head, starting out in headphone mode for so many years. Phil and I, our tastes are pretty aligned, not just in music, but even in food, and film and things like that. So there were moments working remotely when we had to just trust the process. If I was traveling, or Phil was traveling, and one of us had to finish up one part of the song, the trust was 100% there. That’s all part of the fun.”

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.