“In the hands of lesser musicians, this would simply sound sloppy. In D'Angelo's hands, it’s perfectly imperfect – the precise right amount of wrong”: A music professor breaks down the genius of D'Angelo

"He only recorded three albums and a handful of guest vocals, but those recordings possess extraordinary musical depth"

Michael Eugene Archer, known to the world as D’Angelo, passed away on 14 October at the age of 51. He only recorded three albums and a handful of guest vocals, but those recordings possess extraordinary musical depth.

D’Angelo songs have a smooth and inviting surface, but there is always something strange about them, and the closer you look, the stranger they get. In this column, we will examine four of his classic tunes to find out what gives them their uniquely off-kilter funkiness.

Brown Sugar

The title track from D’Angelo’s debut album is a love song. However, it’s not dedicated to a romantic partner, but rather to a strain of Cannabis Indica. It joins the company of such love songs to the devil’s lettuce as the Beatles’ Got To Get You Into My Life and Black Sabbath’s Sweet Leaf.

D’Angelo co-wrote the song with Ali Shaheed Muhammed of A Tribe Called Quest while they were waiting for a crashed computer to reboot (a lengthy procedure back in 1995). D’Angelo was experimenting with a chord sequence on the piano, and Muhammad programmed a beat for them on an Akai S950 sampler.

The S950 only stored about a second and a half of audio at a low bit-depth, so it required significant creativity to get the most out of it. The most distinctive aspect of the beat is the steady “ching ching ching ching” sound. I thought at first that it was a sleighbell, but on closer inspection it sounds more like a pitched-down tambourine layered with a hi-hat. The 12-bit audio gives a crunchy edge to the sound.

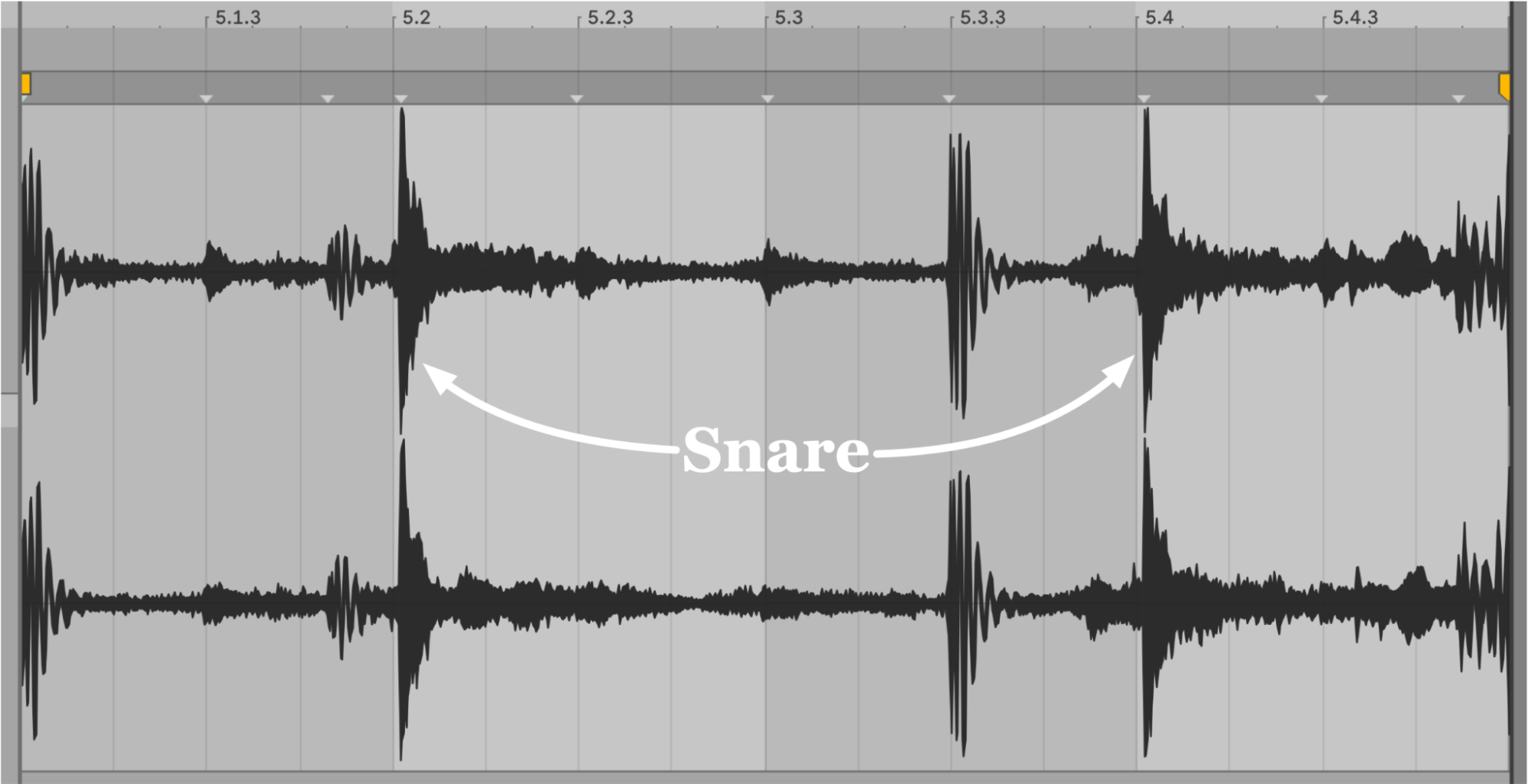

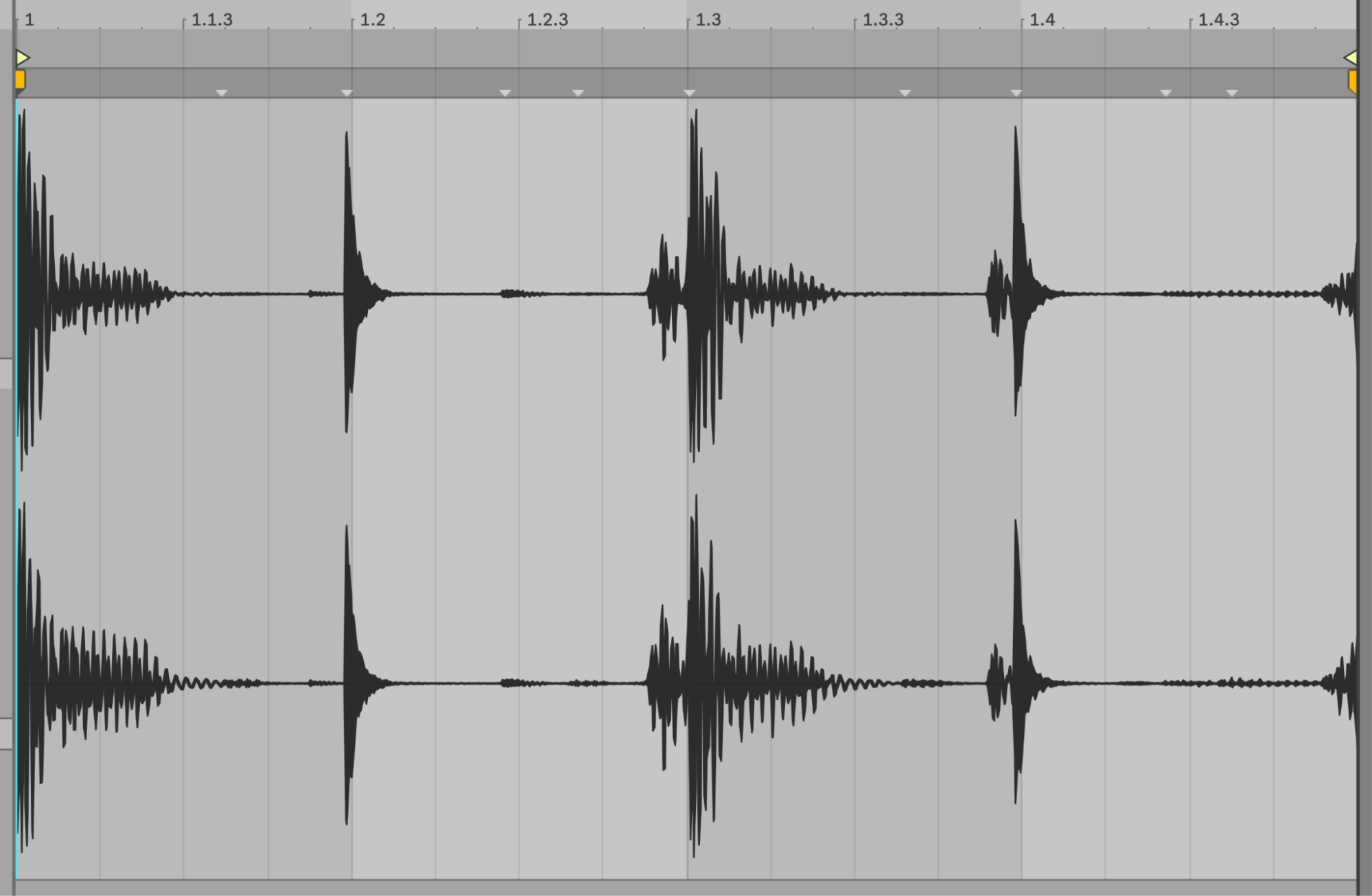

Here’s the audio waveform from the first complete measure of the drum pattern, ten seconds into the track. Each big spike is a drum hit. The two biggest ones are the snares on beats two and four. If you look closely, you’ll notice that they are ever so slightly late. Meanwhile, the 'ching chings' are precisely aligned to the grid, which makes the snare’s offbeat timing that much more apparent.

This kind of slightly wonky groove would become crucial to D’Angelo’s aesthetic, especially after he met J Dilla. Dilla was present either physically or spiritually for many of D’Angelo’s recording sessions, and his drum programming style was a key influence on everyone present. You can learn more about Dilla’s style in Dilla Time by Dan Charnas, a must-read for any fan of this music.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

On Brown Sugar, D’Angelo rides Ali Shaheed Muhammad’s drum groove effortlessly with his Hammond organ. (He’s playing the bassline with his feet on the pedals.) In addition to his smooth falsetto vocals, he also layers in lots of little samples of his singing and speaking, creating a kind of sonic carpet in the background of the track.

Pioneers: How J Dilla and his MPC changed beatmaking forever

Like many D’Angelo songs, Brown Sugar’s harmony is simple but unusual. The entire track is a loop of four chords: Em7, A7, Bm7 and F7. That last chord is the outlier, and we will get to it in a minute. The tune is in B minor, and the first three chords are all from within that key. However, it’s not immediately obvious which chord is the tonic, because they are all also found in E Dorian mode, and the Bm7 chord is in a metrically weak spot. Before the vocal melody comes in, you might reasonably wonder if you aren’t actually in E minor.

The final chord in the loop confounds the confusion. The F7 chord is not from B minor or E minor. This chord is called a tritone substitution. In order to make sense of it, first imagine that the final chord in the loop is B7. This is the dominant chord in the key of E minor, and it sets us up to feel Em as our harmonic home base.

D’Angelo loves to have his vocal melodies fight the chords in subtle ways

The active ingredient in B7 is the tritone between the third, D-sharp, and the flat seventh, A. When B7 resolves to Em, the D-sharp resolves up to E, and the A resolves down to G. Back in the 1940s, jazz musicians noticed that there is another chord that shares the same tritone: F7. The E-flat (enharmonically equivalent to D-sharp) is the flat seventh, and the A is the third. It resolves to Em the same way, but now there’s the extra tension from that very dissonant F, and extra relief when it resolves down to E.

But wait, if F7 is a jazzy setup for Em, how do we know that we’re actually in B minor? Listen to the vocal melody. In the verses, D’Angelo mostly hammers away at the flat seventh A before resolving to B at the end of each phrase. Listen to the opening line: “Let me tell you 'bout this girl, maybe I shouldn't.” The entire line is on A until the word “shouldn’t”, which releases the tension by finally going to B.

The chorus is a more conventional B minor pentatonic, but there is audible friction between that scale and the F7 at the end of each time through the loop. D’Angelo loves to have his vocal melodies fight the chords in subtle ways.

Playa Playa

This is the leadoff track from D’Angelo’s second album Voodoo, considered by many fans to be his masterpiece. It features guitar by Mike "Dino" Campbell, bass by Pino Palladino, drums by Questlove, and trumpet by Roy Hargrove. D’Angelo sings and plays keys. The track includes a looped sample of Players Balling by the Ohio Players.

This song’s most distinctive feature is its deliberately crooked rhythmic phrasing. The bass, guitar and keys are consistently ahead of the drums. You can see it most clearly in the waveform from a measure 43 seconds into the track. Questlove’s snare drums are hitting on beats two and four like you’d expect. Pino Palladino’s bass hits a 32nd note ahead of them. That is tense!

D’Angelo pairs this woozy groove with woozy vocals, densely stacked but mixed quietly and with soft enunciation that makes them sound more like a texture than like actual English words.

As with Brown Sugar, the harmony seems simple, but it has some quirks. The main loop sounds like Fm7, but the guitar and bass are playing F7#9, which includes both the major third A underneath and the minor third A-flat on top. This is known as the “Hendrix Chord” because Jimi featured it prominently in Purple Haze and Foxy Lady. D’Angelo was an admirer of Hendrix and recorded extensively in Electric Lady Studios. Anyway, the key seems like F minor but is really “F blues”.

D’Angelo was an admirer of Hendrix and recorded extensively in Electric Lady Studios

The tune’s other section, starting at 1:05, is a repeated two-bar loop of Fm7, Ab, and Bbm7. You might think that we’re in real F minor now, since the section starts on the same F as the main loop, but no – the vocals and horn part center around the Bbm7 in the back half of the loop, so really we’ve shifted uncertainly to Bb minor. The off-balance harmony is matched by an off-balance form: after the two-bar loop repeats four times, there’s an extra bar of Bbm7. Then this larger nine-bar loop itself repeats three times, making for a 27-bar phrase.

Against all of this ultra-hip backing, D’Angelo’s main vocal melody is weirdly stiff and corny, all on straight eighth notes rather than the swinging sixteenth-note offbeats that the groove would make you expect. But he delivers this melody extremely far behind the beat, deep in the cracks in a way that I’m sure J Dilla approved of.

The Root

This Voodoo tune began as an instrumental by the eight-string guitarist Charlie Hunter. Engineer Russell Elevado recounts that Hunter and D’Angelo had been jamming on some Jimi Hendrix tunes at Electric Lady, and Hunter began playing his instrumental. D’Angelo wrote the melody and lyrics, and also played drums on it. I had assumed it was Questlove on drums; D’Angelo sounds remarkably like him.

Charlie Hunter is a very unusual guitarist. He uses the guitar’s bottom three strings to play basslines while using the top five strings to simultaneously play chords and leads. You normally associate eight-string guitar with prog metal nerds, but Hunter uses it for jazzy funk. You can watch him play The Root and tell its backstory in the video below.

D’Angelo’s beat is a classic limping Dilla feel. Here’s the audio waveform of the first complete measure. The four big spikes are drum hits. The first and third spikes are kicks, and the second and fourth are snares, playing a simple quarter note pattern.

Most people assume that Dilla feel involves dragging behind the beat, and sometimes that’s true. In this tune, however, D’Angelo plays the snares consistently a little bit early. Because they are so loud and crisp, your ear orients around them, and you assume that they must be on time, and that everything else must therefore be a little late by comparison.

Charlie Hunter says in the interview above that he recorded his part conventionally on the beat, and that they must have shifted it a little late during mixing and editing. He’s a little miffed about it, because he thinks it makes it sound like he can’t keep time. “Dilla feel” is evidently a generationally divisive sound; Hunter is ten years older than D’Angelo and formed his sensibilities in the pre-hip-hop world.

The harmony in The Root is smooth and euphonious but deeply confusing

The harmony in The Root is smooth and euphonious but deeply confusing. The main loop is four chords: Em7, G9, Cmaj7 and Fmaj7. I think Charlie Hunter probably conceived of this groove as being in C major, so the chords are iii, V, I, IV. That’s what I hear too, at least, until the vocals enter. However, when D’Angelo comes in, he sings in clear G major, recasting the guitar part as vi, I, IV, bVII in G Mixolydian.

The chorus is more complex, both in terms of its harmony and form. It’s a three-bar loop:

| Cmaj7 Bm7 | Bbmaj7 Ebmaj7 | Dm7 G |

The first bar sounds like IV and iii in G major. The second bar could be I and IV in Bb major or bIII and bVI in G minor. The third bar could be i and IV in D Dorian, or v and I in G Mixolydian. The second time through, there’s an extra bar of Cmaj7 on the end, making the phrases seven bars long. That is unusual!

The final chorus, beginning at 4:34, runs through the three-bar loop eleven times, with D’Angelo layering on more and more ad-libs. Loren Kajikawa talks about this chorus in an article, “D'Angelo's Voodoo Technology: African Cultural Memory and the Ritual of Popular Music Consumption”.

You might think that a minute-and-a-half of the same loop would get boring, but Kajikawa explains that the one-man call-and-response keeps the intensity building through cross-rhythms and countermelodies. Also, D’Angelo’s vocal timbre changes from sweet falsetto to chest and throat sounds with more raspy intensity, evoking the emotional climaxes of gospel music.

Kajikawa calls this “a contrapuntal wall of sound that overwhelms our sense of the original tune”, and says that the effect gives listeners “a visceral sonic representation of what spiritual transcendence might be like.” That sounds like an excellent description of D’Angelo’s music as a whole.

Really Love

D’Angelo co-wrote the first single from his third and final album with Gina Figueroa, who recites the Spanish monologue during the long and cinematic intro. In addition to drums by Questlove and D’Angelo’s keys, the track features two more great instrumentalists: Isaiah Sharkey on guitar and Pino Palladino on bass.

This tune is harmonically the most straightforward of any that we’ve discussed here, but the phrasing is by far the weirdest. The key oscillates between E minor and G major, using simple progressions: ii-V-I in G, and V-I, iv-V-I and ii-V-I in E minor. These are the kinds of changes you hear in jazz standards like Autumn Leaves or Fly Me To The Moon, and they give the tune a comfortable old-timey quality.

However familiar the chords are, however, their placement in musical time is wildly unconventional. The phrases in the verses are two and a half bars long. In the first verse, there are four of these phrases, and the last one has an extra bar tagged on, making the section eleven bars total.

| (4/4) Am7 D7 | (2/4) Gmaj7 | (4/4) B7 Em7 |

| (4/4) Am7 D7 | (2/4) Gmaj7 | (4/4) F#ø7 B7 Em7 |

| (4/4) Am7 D7 | (2/4) Gmaj7 | (4/4) B7 Em7 |

| (4/4) Am7 D7 | (2/4) Gmaj7 | (4/4) Am7 D7 |

| (4/4) Gmaj7 F#ø7 B7 |

How did D’Angelo ever come up with this? And why does it sound so natural? I have no idea. To add to my confusion, this section is a little different every time it occurs, in the intro, the other verses and the guitar solo. These musicians must either be sight-reading a complex chart or just have excellent memories.

The bridge sections are simpler, but with a lopsided harmonic rhythm. The first one arrives at 2:48:

| B7 | B7 Em7 | B7 | B7 Em7 |

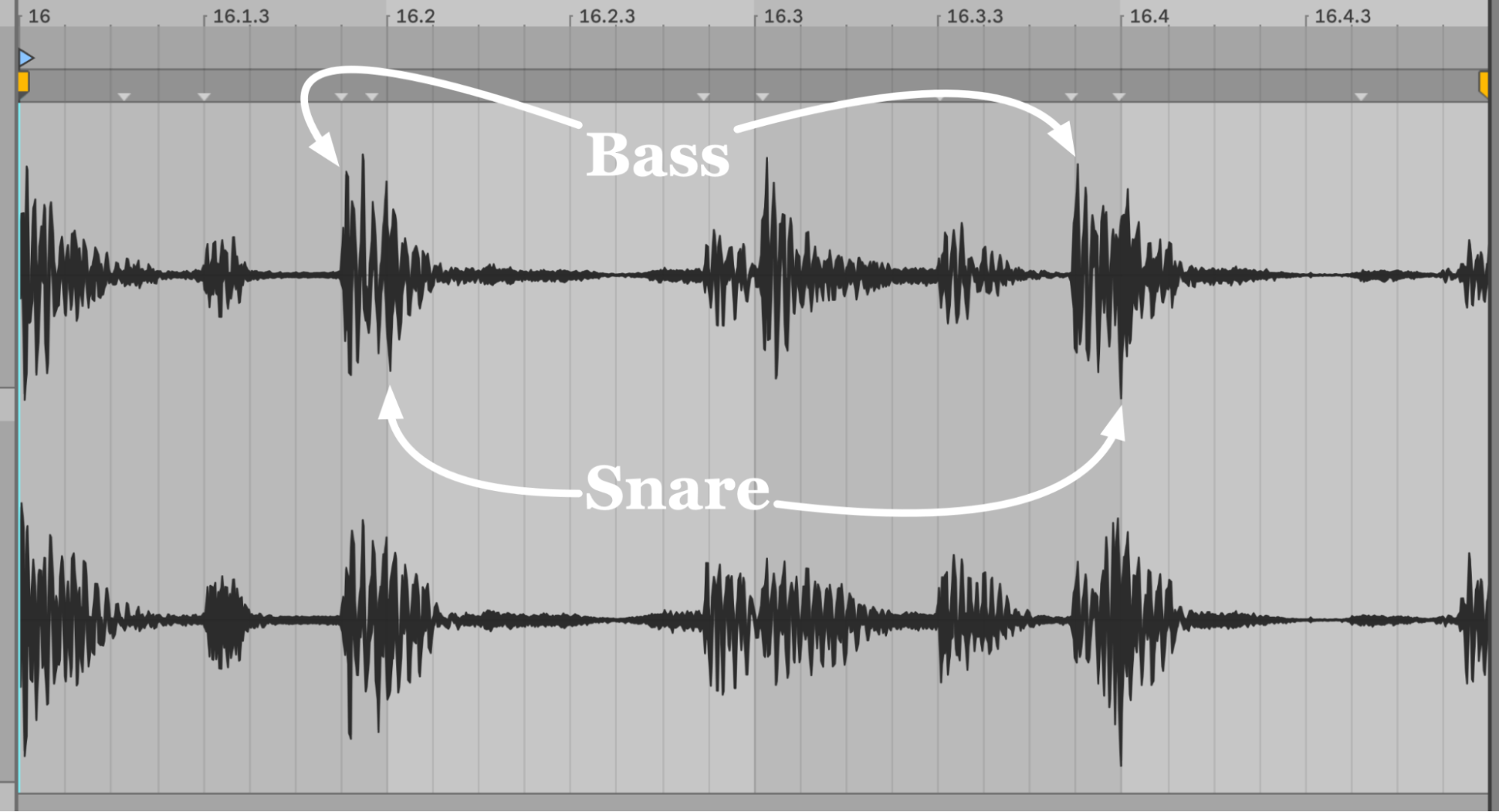

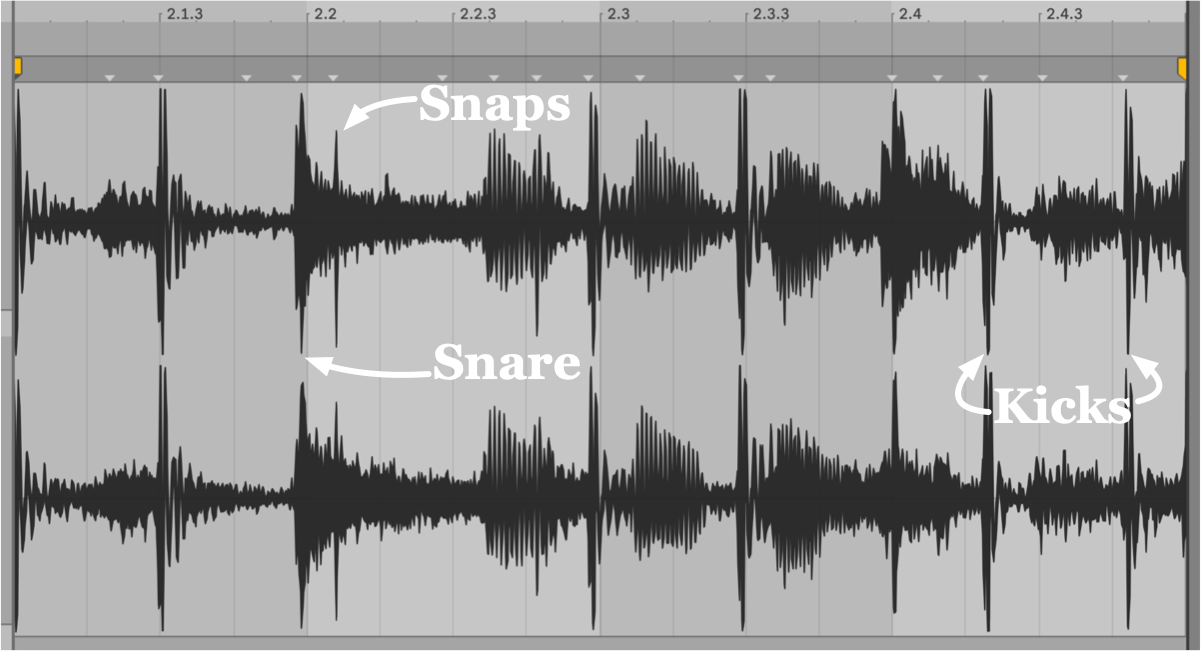

All this strange meter and phrasing is further destabilized by the underlying Dilla groove. Here’s a screencap of the second measure of the main groove, at 1:31.

The snare drum on beat two is a little early, while the layered finger snap on beat two is extremely late. The snap is multiply overdubbed, so it couldn’t possibly be an accident. The kick drums in the final beat are also extremely late.

In the hands of lesser musicians, this much misalignment would simply sound sloppy. In the hands of these players, it’s perfectly imperfect – the precise right amount of wrong, like the angle of D’Angelo’s hat in this Saturday Night Live performance of the tune.

Like many people who stumble upon fame when they are very young, D’Angelo struggled in his personal life. His looks, his personal charisma and his sensual lyrics made him a sex object, especially after the Untitled (How Does It Feel) video, which is one unbroken, lingering shot of his glistening and apparently nude body.

It’s hard to be taken seriously as an artist when the fans are constantly screaming at you to take off your shirt. But D’Angelo was an artist, an excellent one – a songwriter, singer, instrumentalist and producer with few equals. I’m sure that is how he would want to be remembered.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.