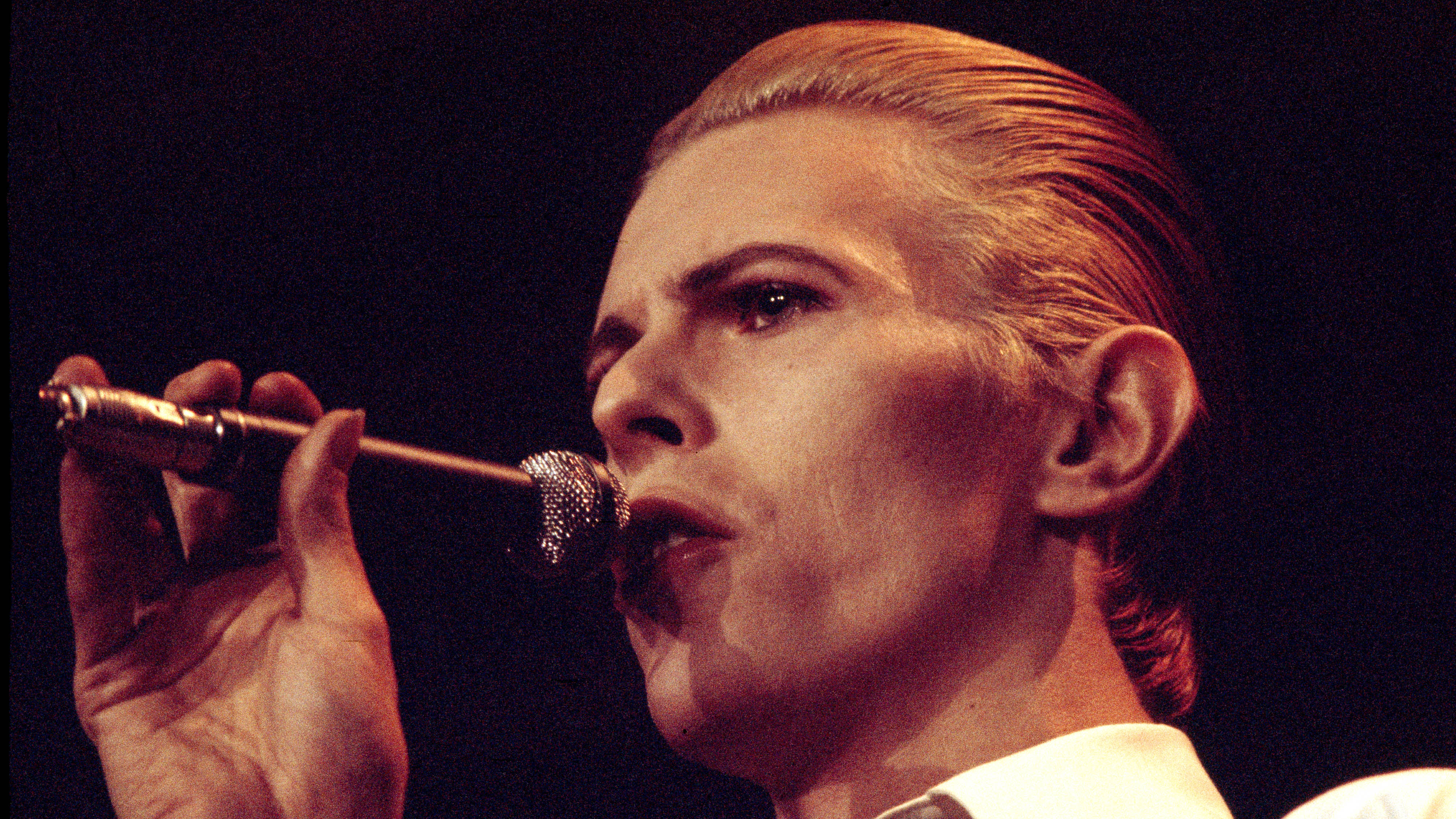

“I have only flashes of making it. I was personally going through a very bad time”: How a disillusioned and drug-addicted David Bowie reinvented his music with a groundbreaking song he could barely remember recording

A dazzling epic that ushered in Bowie’s new persona, the Thin White Duke

One day in September 1975, David Bowie walked into Cherokee Studios at 751 N Fairfax Avenue in West Hollywood to begin recording the song that is now regarded as one of his greatest, Station To Station.

Bowie had only recently returned from New Mexico where he had been cast in Nicolas Roeg’s cult sci-fi film The Man Who Fell To Earth, starring as Thomas Jerome Newton, a humanoid extraterrestrial from a drought-stricken world who crash-lands on Earth.

Bowie’s performance as the gentle, vulnerable and emotionally dislocated Newton, who succumbs to earthly vices such as alcohol and television, was acclaimed by critics. Bowie’s heavy cocaine use at the time only fuelled his depiction of alienation.

In Nicholas Pegg’s book The Complete David Bowie (2000), Bowie recalled that his drug-fuelled state enhanced the feeling that he “wasn’t of this Earth” and made the role feel like a “natural performance”. So natural, in fact, that by the time Bowie began recording Station To Station and the album of the same name, he was arguably still in character.

He was also barely eating. According to writer Emily Barker in a 2018 article in the NME, Bowie “starved his body of all nutrients (besides milk, red peppers, and cocaine)” during the recording.

It was a fragile psychological state. The result was that he had almost no recollection of having recorded the song or the album from which it came.

“I have only flashes of making it,” Bowie said in David Buckley’s 2005 book Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Despite such issues, or perhaps because of them, the song that emerged was a dazzling, multi-part epic that spanned religious mysticism and the occult, and ushered in Bowie’s new persona, the Thin White Duke.

50 years on from its release the song still stands as one of the most thrilling and innovative moments of Bowie’s peerless back catalogue.

Station To Station is a deeply ambitious album, a transitional work which bridges the ‘plastic soul’ of Young Americans (1975) with his Berlin trilogy of albums – Low (1977), Heroes (1977) and Lodger (1979).

Clocking in at over ten minutes long, Station To Station was also the longest studio track of Bowie’s career.

1975 marked a major transition in Bowie’s life. His marriage was falling apart and he was embroiled in a long-running lawsuit to end his management contract with MainMan, the company formed by Tony DeFries in 1972.

Bowie was also disillusioned with Los Angeles, where he lived for much of 1975. Three years later, he told Angus McKinnon of the NME that the city “should be wiped off the face of the planet”.

In April 1975, as noted by Cameron Crowe, Bowie announced his retirement. “I’ve rocked my roll,” he said. “It’s a boring dead end. There will be no more rock ’n’ roll records or tours from me. The last thing I want to be is some useless fucking rock singer.”

The retirement was short-lived. By September, he was looking towards Europe, inspired by the work of artists such as Neu!, Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream and Brian Eno.

“The overriding need for me was to develop more of a European influence, having immersed myself so thoroughly in American culture,” recalled Bowie in a 1983 interview with Musician magazine. “As I was personally going through a very bad time, I thought I had to get back to Europe.”

Bowie’s co-producer on the Station To Station album was Harry Maslin, who had worked on tracks such as Fame, Bowie’s collaboration with John Lennon.

It was Maslin who selected Cherokee Studios as the location for recording Station To Station. Cherokee had only just opened and boasted a custom 80-input A-Range mixing console, one of the first in the US.

Artists were quickly drawn to the warm analogue sound of the new studio, which featured five live rooms, 24-track mixing consoles, 24-hour session times and a lounge bar. It also boasted a 35 x 58 ft live room, known as ‘Frank Sinatra’s string room’ after the legendary crooner recorded The Sinatra Christmas Album there in October 1975.

Cherokee’s 24-hour opening times proved hugely appealing for artists. With no time constraints and the advanced studio technology, it was a perfect environment for the Station To Station album to take on an experimental ethos. But Maslin had other reasons for selecting this studio. It was new, quiet and attracted far less media attention.

Bowie didn’t need much convincing. He reportedly arrived at the studio on the first day, sang a few notes in Studio One, played a piano chord and said, “This will do nicely.”

Some of the musicians on Station To Station had featured on the Young American sessions. These included guitarists Earl Slick and Carlos Alomar, and drummer Dennis Davis. One addition was bassist George Murray, who would go on to play on the next five Bowie albums after Station To Station.

Bowie’s old friend Geoff McCormick, later known as Warren Peace, was brought in on backing vocals, while Harry Maslin provided effects. At the suggestion of Earl Slick, keyboardist Roy Bittan from the E Street Band was brought in to contribute piano and organ on Station To Station, to replace the departed Mike Garson.

“David knew we were coming to town and he wanted a keyboard player,” Bittan told Rolling Stone magazine in 2015. “It must have only been about three days. It's one of my favourite projects I've ever worked on.”

The song Station To Station is directly influenced by Bowie’s extreme cocaine addiction at the time and his dark and paranoid state of mind during its recording. This is referenced directly in the lyrics. “It's not the side-effects of the cocaine/I'm thinking that it must be love,” he sings.

Across its 10 minutes and 14 seconds running time, the song blends the lean funk of Young Americans with experimental sounds. Bowie looked towards the austere synth-dominated soundscapes of artists such as Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream.

Details are hazy about when exactly the song was recorded, but it was seemingly created across a two month period along with the rest of the Station To Station album.

The song opens with a train-like noise, echoing Kraftwerk’s seminal 1974 track Autobahn, which begins with the closing of a car door, the starting of an engine and the sound of the car being driven away being panned across the two stereo speakers.

The train sound on Station To Station was reportedly created by Earl Slick using flangers and delay effects. The sound then pans from right to left across the stereo channels before fading. Bowie biographer Nicholas Pegg likened this to a train “disappearing into a tunnel”.

In a 1977 quote for the Sound And Vision liner notes, Bowie praised the sounds and textures that Slick contributed. “I got some quite extraordinary things out of Earl Slick,” he recalled. “I think [Station to Station] captured his imagination to make noises on guitar and textures, rather than playing the right notes.”

Slick’s train-like sound is evocative as it swirls and pulsates, while a suggestion of brakes or a whistle, 30 seconds in, fuels the illusion.

According to author David Buckley in his 2005 book Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story, the only memory that Bowie later had of the sessions was “standing with Earl Slick in the studio and asking him to play a Chuck Berry riff in the same key throughout the opening of Station To Station”.

At 1:08, a thick squall of feedback enters the mix as the train noise subsides, and one by one the band members enter, with percussion and keyboards playing chords in and out of key. Bittan’s ominous C#-C piano motif is soon underpinned by George Murray playing a punchy G-A pattern on the bass, which would become a defining element of the song.

At 1:53 the whole band kicks in, with Dennis Davis laying down a hefty, dexterous groove, a slow march of sorts beneath an Am-F-G chord pattern. Clipped pizzicato-style guitar and rattling percussion occupy the higher frequencies while Slick’s squalling feedback dips and dives. It’s an engaging sonic stew with enough spiky, atonal elements to give it edge.

It takes 3 minutes and 19 seconds for Bowie’s voice to finally appear. The drums stop and the whole song opens up into a beautiful refrain over a Cm-G-F#m--D chord progression: “The return of the Thin White Duke/throwing darts in lovers’ eyes”. Bowie’s voice sounds rich and full, his deep croons bolstered by rich backing vocals from Warren Peace.

Lyrically, Bowie drew on an array of religious and mystic texts. These included the works of Aleister Crowley, the Russian occultist Helena Blavatsky, as well as works on the Tarot, Kabbalah, black magic, numerology, the Third Reich, and other written works on religion and conspiracy. And contrary to one prevailing view, the song is not about the railway network.

“The Station To Station track itself is very much concerned with the stations of the cross,” Bowie is quoted as saying in an article in MOJO magazine in October 2025. “All the references within the piece are to do with the Kabbalah. It’s the nearest album to a magik treatise that I’ve written. I’ve never read a review that really sussed it. It’s an extremely dark album. Miserable time to live through, I must say.”

Lyrically, it is dense and dramatic. “One magical movement/from Kether to Malkuth 1/There are you/You drive like a demon.”

Several verses later, at 5:20, the whole thing shifts tempo as the band lurch into what sounds like a disco-infused prog rock suite, with Bittan’s piano vamps and some sprightly funk rhythms from Carlos Alomar.

A searing overdriven guitar solo piles in at 7:40. From that point out Bowie and the band pretty much jam it out to the end.

Station To Station was released as the opening track to the album of the same name on 23 January 1976. It was released as a promotional single in some countries such as France – edited down to a lean 3:40 and featuring TVC15 on the B-side – although it largely remained an album track.

The song ushered in a whole new era of experimentation for David Bowie and was warmly received by critics. Alex Needham of The Guardian described the song as “monumental”, going on to write that “Bowie blasts away his immediate Philly soul past and speeds into a more experimental future over 10 totally exhilarating minutes”. The fact that the song didn’t overshadow the rest of the album, noted Needham, demonstrated just “how much Bowie was on fire”.

In his 2012 book The Man Who Sold The World: David Bowie And The 1970s, author Peter Doggett acknowledged Station To Station’s significant sonic shift.

“Here was Bowie's first nod of recognition to the so-called motorik sound of Krautrock,” wrote Doggett, “as the ominous, Wagnerian strains of the early segments of the song were succeeded by the propulsive dance rhythms of the finale.”

Station To Station was a cathartic moment, concluded Doggett, “suggesting that the spiritual journey might just be beginning.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.