“He said ‘Look, I want you to take all those albums and destroy them'”: Why did Prince abruptly retract his new album days before release in 1987?

A record allegedly driven by supernatural forces, Prince swiftly disowned the stark funk of the Black Album - but what caused him to pivot so dramatically?

It’s common that artists come to resent their most popular work, Kurt Cobain soon developed a distaste for Smells Like Teen Spirit and its chart-busing parent album, Nevermind, REM’s Michael Stipe grimaces at the mention of Shiny Happy People and just try and ask Thom Yorke about Creep, we dare you.

But while artists often develop less-than-positive hindsight perspective of output that might have shifted their creative trajectory, it’s extremely rare for a musician to create, record and mix a whole album, have hundreds of thousands of copies pressed, and then, out of nowhere, startlingly make the call to abandon it, a matter of days before it was due to hit shelves.

Few had the power to make such a call. One man who did, was Prince.

The infamous aborted record in question was originally intended to be the follow-up to Sign o' the Times. A title-less, completely black-sleeved, LP that is now universally known as the 'Black Album’. Slated for release on the 8th of December 1987, Prince pulled it at the eleventh hour.

So, just what motivated Prince to ditch a record he'd spent months working on so close to the wire?

By all accounts, the ‘epiphany’ moment came on the night of Tuesday December 1st 1987. It's a calendar date forever enshrined in Prince mythology as ‘Blue Tuesday’.

The tale is often told that Prince was gripped by the belief that potentially evil, demonic entities were guiding his hands and mind towards making a record suffused with negative energy.

Prince then was compelled by a spiritual duty to prevent the record hitting the ears of the masses.

To interrogate the truth of this wild story, we have to provide a little context…

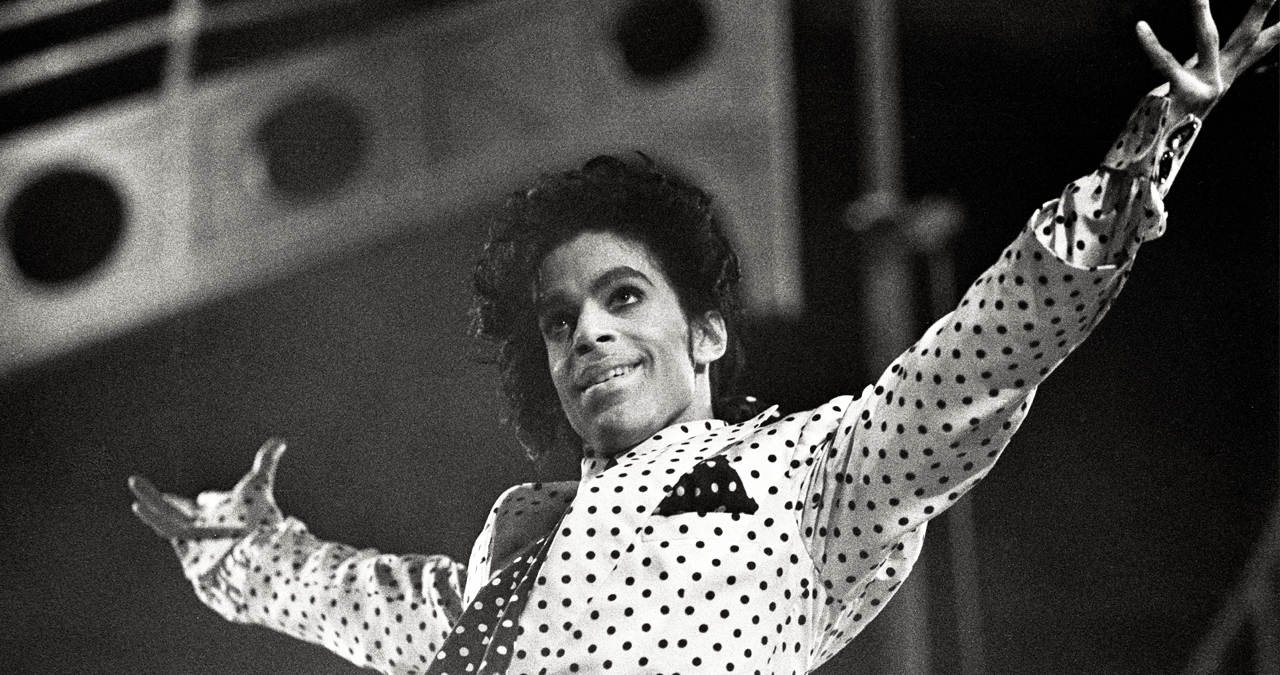

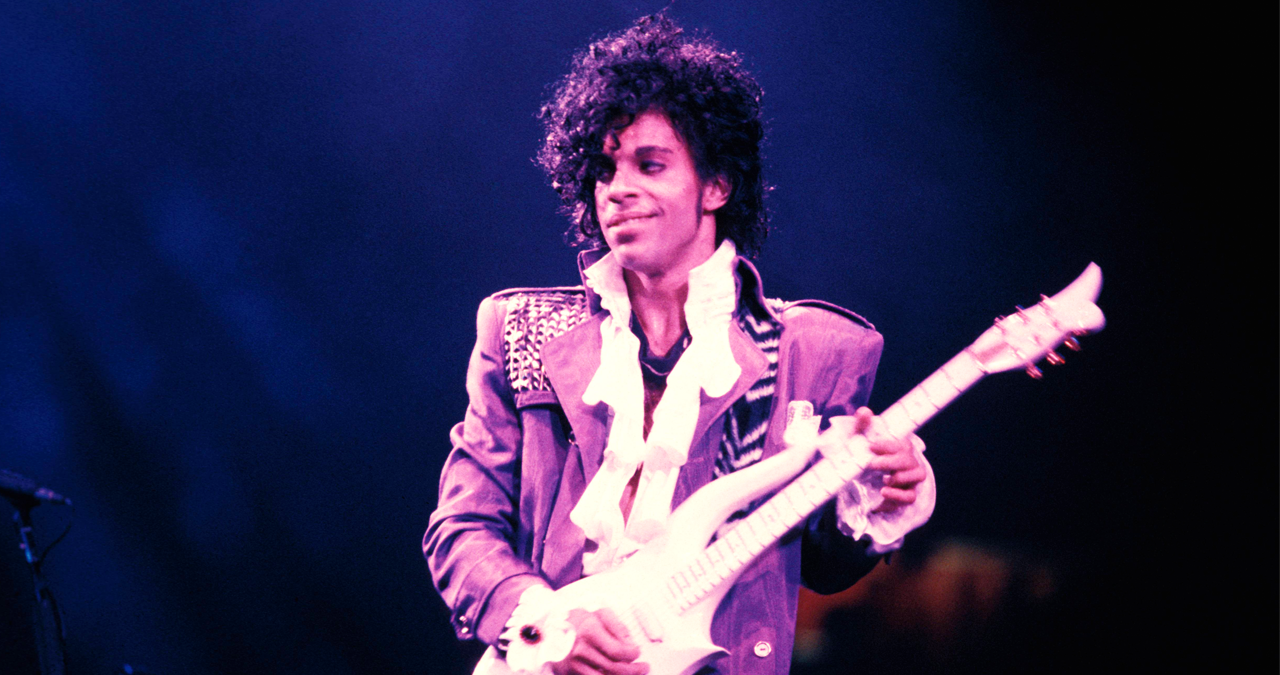

On the heels of the exceptional double-album, Sign o’ the Times, released in March of 1987, Prince was buoyed by a surge of creativity.

Invigorated by new technology such as the Fairlight CMI and the Linn LM-1 drum machine, and wallowing in world-beating chart success, Prince had reached that admired position, like the Beatles before him, of being able to have unfettered free rein to explore whichever musical ventures he saw fit to pursue.

But there was an itch that Prince just couldn't scratch.

A few had criticised the more chart-aligned, epic sweep of his most recent work, and his stadium rock-adjacent posturing in general.

To those critics, Prince had ‘sold-out’ his principles in favour of commercial clout.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Determined to prove them wrong, Prince shifted direction and cut a record that was more pointedly directed at his black audience. Perhaps motivated by a fear, as suggested by some commentators, that he was in danger of losing them by dent of his guitar-toting, rock-leaning post-Purple Rain stature.

Originally dubbed ‘The Funk Bible’, the basic shape of many of the tracks that became the Black Album were first rustled up spontaneously in an attempt to write ‘music to dance to’ at drummer Sheila E’s upcoming birthday party.

Across these tracks, Prince - channelling his artistic alter-ego Camille - carved out a peeled-back variant of funk rock, married to surreal and somewhat jarring lyrics with typically inventive, proto-electronic flavouring.

Though by no means an outright Prince masterwork, there was some true gold amongst Prince’s Black Album set, from the tight, hypnotic funk of Superfunkycalifragisexy, the all-night-energy of Le Grind and the simmering kineticism of Rockhard in a Funky Place.

Nothing evil to see here. This was tight stuff.

In the words of engineer Susan Rogers, speaking to the BBC in 2012, the Black Album represented a fitful exercise in tension release after the focussed, creative intensity of Sign o' the Times.

“Those [Sign o' the Times] songs require a bit of time to write and produce and record. So Prince needed a break from all that. He just wanted to make some funky dance music, because he wanted music to dance to at Sheila's party.”

But the other side of the coin came a series of tracks fuelled by those underlying grievances. The sinister track Bob George was a portmanteau of two very real people who loomed large in Prince's mind.

First, there was (soon to be ex-) manager Bob Cavallo with whom Prince had a fractious relationship, and music journalist Nelson George. While broadly positive about Prince’s work, George's criticism of his Parade-era output had stuck in Prince's craw. Perhaps he had a point?

Then there was the hip-hop-parodying Dead on It, which took a dismissive swipe at the nascent genre’s emerging tropes. It was clear that the album was, at least in-part, stemming from the more insecure side of Prince’s psyche.

But upon completion of the record, Prince was generally happy with it.

A blunt counterpoint to the dense Sign o' the Times, the Black Album would suffice as the ‘next Prince album’ for now. A holding pattern until true inspiration struck.

It wouldn’t be long before that very thing happened.

Back to that infamous ‘Blue Tuesday’ of December 1st 1987…

That night, Prince and his entourage had met soon-to-be protégé, poet and songwriter Ingrid Chavez at a bar. Enamoured by her, Prince asked if she wanted to come back to Paisley Park and listen to the - as yet unheard - new record?

“We had met Ingrid Chavez that night, at a club in uptown - Williams Pub I think it was,” recalled Prince’s Director of Security, Gilbert Davison on the Funkatopia podcast in 2022.

“So we went back to play the album. I was waiting [in the lobby] to go home because it was late,” Davison continues. “Then he came out and said, ‘I’m not going to do the record.’"

What happened next is the stuff of Prince legend - frantic phone-calls were made to executives, and demands that the record be immediately destroyed were levelled. Costs, Prince made clear, didn’t matter one iota.

“I was awakened by a call from our [Paisley Park] office manager, Karen Krattinger,” recalled Prince’s tour manager and industry go-between Alan Leeds, in an interview with Wax Magazine. “Karen worked very closely as a personal assistant to Prince, and he had called her in the middle of the night insisting that the Black Album be stopped.”

The resulting incurred cost was going to be substantial. 500,000 copies of the Black Album had long since been pressed and were sat in boxes, awaiting distribution to record stores across the US ahead of its launch on December 8th.

“We told him we had spent a lot of money getting this thing ready for market,” Former Warner Brothers executive Mo Ostin told Billboard. “He said “Look, I want you to take all those albums and destroy them and I’ll pay for whatever cost you guys incurred in manufacturing.” And he actually paid us out of his royalties.”

So, just what happened?

It seems there’s, at the very least, three possible answers to that question.

The first, and most regularly-cited, seems to be a particularly intense reaction while partaking in recreational drugs. This is borne out by a few sources, who claim that on that same night, a euphoric Prince called them to tell them that he loved them.

Prince’s trusted engineer and producer, Susan Rogers is perhaps the most compelling source on this angle…

“It was two in the morning and [Paisley Park] was empty,” Rogers recalled in Per Nilsen’s Dance Music Sex Romance: Prince: The First Decade. “It was dark except for a couple of red candles and I heard a woman's voice say 'Are you looking for Prince?' I found out later the woman was Ingrid Chavez. And I said 'Yes. I'm supposed to meet him here at 2 am'. She said 'Well, he's here somewhere’”

Rogers continued, “As I came out of the room, I suddenly came face to face with him and I'm certain he was high. His pupils were really dilated and he looked unlike I'd ever seen him look before. He looked like he was tripping,” Rogers stated. “He was standing very close to me and he asked, 'I just want to know one thing. Do you still love me?' And I said that I did and that I knew he loved me. He said. 'Will you stay?' And I said 'No. I won't. Goodnight'. I headed to the door. It was really scary.”

The intense drug trip-theory isn’t the only potential answer, others cite his evolving spirituality and growing reliance on communing with higher powers when deciding his next move. Prince would later suggest that he spoke to 'God' that evening, who told him not to put the album out.

Meanwhile, backing vocalist and choreographer Cat Glover maintained that she had been present on Blue Tuesday, and that - although she recalled that Prince had been partaking in substances that evening - affirms that his choice to scrap the record was dictated by something more spiritual.

“He opened up his heart and told me things that I’m sure he had never told anyone before,” Glover told Wax Magazine. “He loved that album, but it seemed dark to him. Something hit him that night that made him change - an enlightenment, a higher power.”

Prince would later double-down on the notion that the record was, in a sense, ‘evil’.

He even had a name for the very demonic presence that fuelled the record: Spooky Electric.

The mystique-stoking ‘Camille’s Poem’ found within the Lovesexy tour programme the following year is either the most intriguing insight into Prince’s contemporary reasoning for pulling the record, or an exercise of impish lore-building;

Tuesday came. Blue Tuesday.

His canvas full and lying on the table,

Camille mustered all the hate that he was able.

Hate 4 the ones who ever doubted his game.

Hate 4 the ones who ever doubted his name.

“Tis nobody funkier — let the Black Album fly.”

Spooky Electric was talking, Camille started 2 cry.

Tricked.

A fool he had been. In the lowest utmostest.

He had allowed the dark side of him 2 create something evil.

A trusted friend, confidante and employee, Gilbert Davison, strongly disputes that Prince took any form of drug that night, and instead points to a third motivation.

The pulling of the Black Album wasn't the end result of a drug trip, or religious epiphany, instead it was a gradually gnawing realisation, during that playback to Ingrid, that the album just wasn't that good.

Instead, inspired by his meeting with Chavez, Prince felt fired-up to make the artistically richer Lovesexy, and suddenly gained a new perspective on the sub-par Black Album.

“I never saw Prince take drugs, it just wasn’t his thing,” Davison told Funkatopia, who then cited a trio of abandoned projects shelved prior to the making of Sign o' the Times.

“For Prince [cancelling a whole album] was normal,” Davison continued. “You could have any conversation with this guy and he could turn that into more than just a thought.”

Davison also revealed that later that evening, he had said ‘welcome back’ to his seemingly happier friend and boss - whom he’d observed being in a gloomy mood for a few weeks. A weight seemed to have been lifted, it seemed.

Whether any drugs played a part or not, it was clear that Prince suddenly foresaw a new way to spend the looming 1988. That path would lead to Lovesexy - an adored central text of Prince’s canon.

Meanwhile, rather than being that most feared of things, a boring stop-gap, the esoteric allure of the 'evil' Black Album instead became a highly-sought after mythological artefact, coveted by the most dedicated of Prince's fanbase.

"We had no idea [The Black Album] was going to be this sought after, bootlegged, huge thing," said Davison. "It became this mysterious record. That never crossed our mind.”

Although the majority of copies were destroyed, a few were salvaged and duplicated on the bootleg market. Soon crummily-taped knock-offs were being passed around with awe and reverence. It would end up being one of the most bootlegged albums of all time.

Its sinister aura was, perhaps knowingly, encouraged by Prince who, in the video for Lovesexy single Alphabet St, included a split-second frame which read 'Don't buy The Black Album, I'm sorry.'

If Prince was being genuine in his plea, it roundly failed. The message only served to heighten the intrigue.

Eventually The Black Album was commercially released on November 22nd 1994 as a strictly limited edition before being deleted on January 27th 1995. Prince received a hefty sum to allow to the record to finally get its time in the sun, but still decried it as a record he was 'spiritually against'.

It would later be exclusively re-released on the Tidal platform and is now widely included in conversations about Prince's discography. Removed from its mystical context, while certainly a decent Prince record, it was clearly never going to be a standout in a body of work as bountiful as his.

Prince himself, was fairly revelatory - and honest - when pressed on the subject in a 1990 interview with Rolling Stone. Prince's response backs up Davison’s memory of the notion that it simply wasn't up to scratch.

“I suddenly realised that we can die at any moment, and we’d be judged by the last thing we left behind. I didn’t want that angry bitter thing to be the last thing. […] That doesn’t mean I don’t like the music, but I don’t want the people to feel that kind of depression coming through in my music”.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.