“When I asked him what he thought of what I was doing, glam rock, he said, ‘Yeah, it’s great, but it’s just rock ’n’ roll with lipstick on!’”: How David Bowie and John Lennon bonded to create a funky No.1 hit that slammed celebrity culture

“We spent hours and hours discussing fame," Bowie said

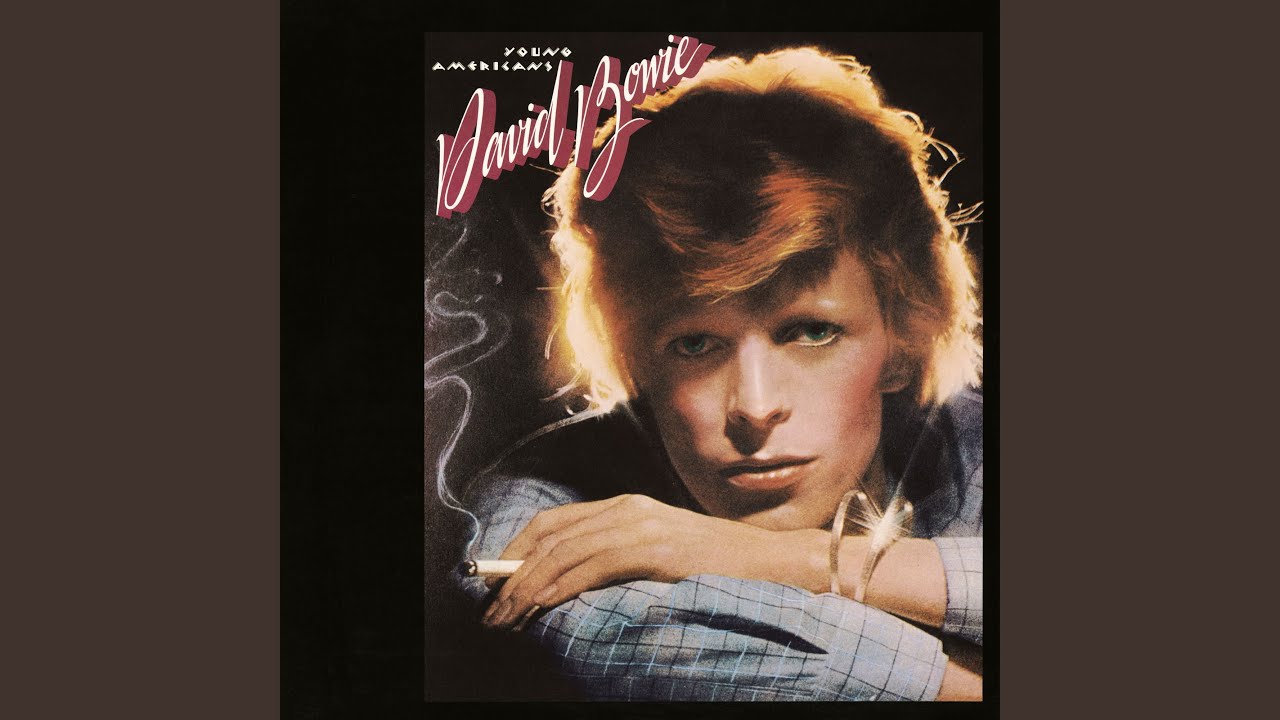

David Bowie was in the closing stages of recording his Young Americans album when he decided to record a cover of The Beatles’ Across The Universe — primarily as a strategic move to entice John Lennon to come down to the studio.

It was January 1975 at Electric Lady Studios in New York’s Greenwich Village, and Lennon had only just reunited with Yoko Ono after his infamous ‘lost weekend’ period of estrangement.

Lennon accepted Bowie’s invitation, but any thoughts of Across The Universe were soon forgotten.

Instead, over the course of one day, Bowie, Lennon and guitarist Carlos Alomar wrote and recorded a whole new song — Fame, a biting critique of stardom and celebrity that blended funk and soul with Bowie’s idiosyncratic avant-garde style.

The song would give Bowie his first No.1 single in the US, knocking Glen Campbell’s Rhinestone Cowboy off the top slot, and giving him his first crossover success in the United States.

The song’s lean, muscular funk groove — self-deprecatingly dubbed “plastic soul” by Bowie — alienated many fans, particularly in the UK.

But as ever, Bowie’s creative instincts were flawless.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

50 years on from the release of Fame, the song still sounds vital, fresh and remains an enduring classic within his peerless back catalogue.

Bowie and Lennon first met via actress Elizabeth Taylor on 20 September 1974. Four days earlier Taylor had attended a Bowie concert in Anaheim, and she and Bowie quickly became good friends.

Taylor invited Bowie to the 21st birthday party of Dean Martin’s son Ricci, in Beverly Hills. When Bowie arrived he found Taylor talking to John Lennon, his then partner May Pang, and Elton John.

“I think we were polite with each other, in that kind of older-younger way,” recalled Bowie in a speech while receiving an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of Music in 1999. “Although there were only a few years between us, in rock ’n’ roll that’s a generation, you know?

“So John was sort of [in Liverpool accent] ‘Oh, here comes another new one’. And I was sort of [thinking] ‘It’s John Lennon! I don’t know what to say. Don’t mention The Beatles, you’ll look really stupid’. And he said, ‘Hello, Dave.’ And I said, ‘I’ve got everything you’ve made – except The Beatles’.”

Bowie made contact with Lennon again at the beginning of January 1975.

In a 2021 BBC Radio 4 and 6Music programme called Bowie: Dancing Out In Space, producer Tony Visconti recalled that Bowie was terrified of meeting Lennon again and asked Visconti to accompany him to “buffer the situation”.

Visconti recalled: “About one in the morning I knocked on the door and for about the next two hours, John Lennon and David weren’t speaking to each other. Instead, David was sitting on the floor with an art pad and a charcoal and he was sketching things and he was completely ignoring Lennon.

“So, after about two hours of that, he [John] finally said to David, ‘Rip that pad in half and give me a few sheets. I want to draw you’. So David said, ‘Oh, that’s a good idea’, and he finally opened up.

“So John started making caricatures of David, and David started doing the same of John, and they kept swapping them and then they started laughing and that broke the ice.”

One week later, Lennon arrived at Electric Lady Studio after being invited by Bowie, for the one-day session that would yield Fame.

It was guitarist Carlos Alomar who provided the sonic catalyst for the creation of the song that became Fame.

Bowie had asked Alomar to come up with a guitar riff for a cover of Foot Stomping, the 1961 hit by Los Angeles doo-wop group The Flares, with the idea that he and Lennon might record it.

But when Bowie heard the infectious riff that Alomar had created, he immediately latched on to it and deemed it too good to waste on a cover version.

Alomar’s riff is a funky and infectious one-line syncopated phrase, built around the chord of F7. It’s a simple yet powerful hook that inspired both Bowie and Lennon.

Opinions vary as to exactly who was in the studio that day. Certainly, Bowie, Lennon, Alomar and producer Harry Maslin were. And it seems likely that the core band on Young Americans — guitarist Earl Slick, bassist Emir Ksasan and drummer Dennis Davis — were also present, as were Bowie’s backing vocalists Ava Cherry and Luther Vandross.

But in his autobiography, Guitar, Earl Slick recalls meeting Lennon — for what he thought was the first time ever — five years later on the sessions for Lennon’s Double Fantasy album in 1980.

When Slick walked over to Lennon and said, ‘Good to meet you’, Lennon reportedly laughed and said ‘Good to meet you again’.

Slick wrote of Lennon: “He insisted we met during the Young Americans sessions, but I didn’t remember any of it. I took his word for it, though, because he seemed sure and I was pretty out of it in 1975, so anything was possible!

"I mean, my fingers were working just fine, because the record sounds okay, but who knows where my brain was at. But how could I forget meeting John Lennon?”

On that January day in 1975, as Alomar played his cyclical riff, Lennon began singing the word ‘Aim’ over the pattern, which Bowie soon changed to ‘Fame’. From that point, the song took on its own momentum.

Lyrically, the song hones in on the hollowness of celebrity, examining Bowie’s disaffection with stardom, the destructive nature of fame and the immense pressures it places on artists. It was a subject that Lennon clearly had a great deal of experience of too.

By 1975, the subject of fame had a far more personal and literal meaning for Bowie.

He was embroiled in impending lawsuits that would result in the end of his relationship with manager Tony Defries over a costly musical theatre project called Fame, conceived by Defries and his company MainMan.

The show closed after just one night on Broadway and its failure had a devastating impact on Bowie and Defries’ relationship.

Bowie would go on to describe the song Fame as “nasty, angry” and admitted it was written with “a degree of malice” which was aimed at MainMan.

As Peter Dogget noted in his 2012 biography The Man Who Sold The World: Bowie And The 70s: "Every time in Fame that Bowie snapped back with a cynical retort about its pitfalls, he had [Defries] and [Defries's] epic folly in mind."

Doggett cited the line "bully for you, chilly for me" as an example.

Lennon also had a similarly sour experience, reportedly telling Bowie that he had been cheated out of money.

The whole subject of fame inspired Bowie and Lennon to vent their own feelings and experiences through the song, throwing lines about in a fast and furious creative fusion.

Questions have been raised over the extent of Lennon’s contribution to the writing of Fame.

In his book, Doggett suggested that Lennon made the “briefest lyrical contributions” but Bowie later said that Lennon was the energy and inspiration for the song, which was why he received a songwriting credit along with Bowie and Alomar.

Fame is an inspired work. Alomar’s guitar riff is both rhythmic and melodic, a spiky and spidery funk line that anchors and elevates the whole track. Maslin and Bowie’s production is inspired as they take Lennon’s acoustic rhythm track and twist and corrupt it with myriad techniques, while the vocals are transformed into both rhythmic and melodic elements.

Bowie contributes stabs of fuzz-drenched guitar that are positioned like a brass section in the mix. The whole approach is one of angular techniques and boundless levels of lateral thinking.

Fame was released as the second single from the Young Americans album on 2 June 1975 in the United States and on 25 July in the UK.

While it reached only No.17 in the UK, it rose to No.1 in the States.

In a 1987 issue of US publication Musician, Bowie said he had “absolutely no idea” the song would do so well, adding: “I wouldn't know how to pick a single if it hit me in the face.”

The song thrust Bowie into the mainstream and opened up a whole new vista of opportunity, such as in November 1975, when he appeared on the iconic TV programme Soul Train.

Bowie later confessed he was extremely nervous and had a few drinks to calm himself before appearing on the show.

Fame and the album Young Americans marked a whole new blue-eyed soul and R&B direction for Bowie, one that he would pursue until embracing electronic music on Station To Station (1976).

The Fame collaboration was the beginning of a special friendship between Bowie and Lennon, forged by mutual admiration. It was a friendship that would last until Lennon’s tragic death in 1980.

On the JohnLennon.com site there is a comment Lennon made about Bowie: “I must say I admire him,” Lennon said. “The vast repertoire of talent the guy has. I was never around when the Ziggy Stardust thing came because I’d already left England, so I really didn’t know what he was, and meeting him doesn’t give you much more of a clue because you don’t know which one you’re talking to… but we seemed to have some kind of communication together and I think he’s great. The fact that he can just walk into that and do that. I could never do that.”

For Bowie, the collaboration and subsequent friendship was particularly special.

“It was just a joy to work with him in the studio that one time,” said Bowie, also quoted on the JohnLennon.com site. “When I asked him what he thought of what I was doing, glam rock, he said, ‘Yeah it’s great, but it’s just rock and roll with lipstick on!’ I was impressed, as I was at virtually everything he said.

“He was probably one of the brightest, quickest-witted, earnestly socialist men I’ve ever met in my life… a real humanist. And a really spiteful sense of humour, which of course being English, I adored.”

Bowie recalled that as their friendship developed, he and Lennon spent a lot of time getting to know each other in “a lot of bars” in New York.

“We spent hours and hours discussing fame, and what you had to do to get it, to get there," Bowie said. "If I’m honest it was his fame we were discussing, because he was so much more famous than anyone who had been before.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.