“They were doing things nobody was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous”: How the Beatles won over America with one performance

We look back on that magical night when John, Paul, George and Ringo entranced a grieving nation and fired up the engine of Beatlemania stateside

On the night of February 9th 1964 something extraordinary happened. A scant two and a half months since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963 had deflated the optimism of a new decade, a besieged nation looked again to those newfangled machines sat in the corner of their living rooms.

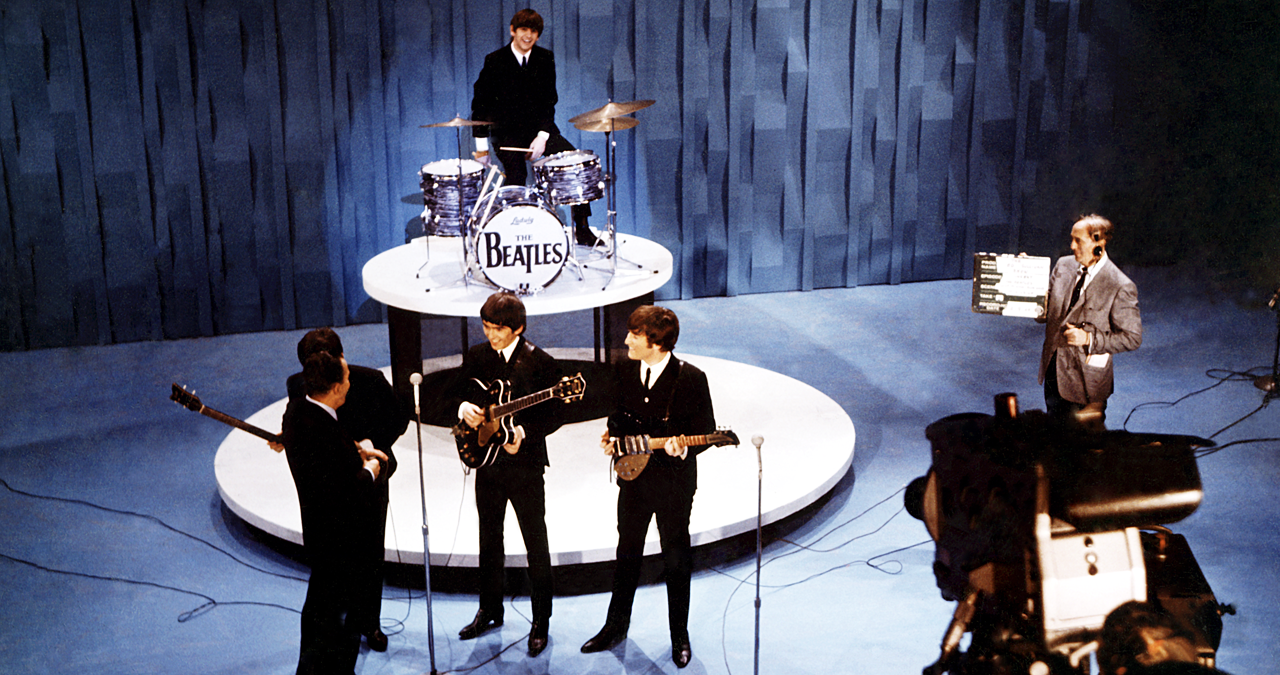

They'd promised so much, these television sets, yet instead had provided a window on horror beyond imagining. But, tonight, this still ultra-modern contraption was offering Americans a front row seat for what was Europe was insisting was the next biggest thing in music. The Beatles were appearing for the first time on US TV.

For newcomers to the Beatles myth, it might seem somewhat hyperbolic to look back on the group’s first Ed Sullivan Show television appearance with such grandiosity.

Indeed, the black and white footage of the four mop-topped Beatles, sealed in their formal suits, delivering heartfelt songs to delirious female screams might seem fairly anodyne through a 21st century prism, especially when stacked against the media-saturated landscape which we all now live.

Yet, for many of the future innovators of rock and pop, this was the fountainhead moment, out of which everything else flowed.

“I wasn’t prepared by how powerful and totally mesmerising they were to watch. It changed me completely,” Aerosmith’s Joe Perry told us back in 2009. “I knew something was different in the world that night. Next day at school, the Beatles were all anybody could talk about. Us guys had to play it kind of cool, because the girls were so excited and were drawing little hearts on their notebooks: ‘I love Paul,’ that kind of thing. But I think there was an unspoken thing with the guys that we all dug the Beatles, too. We just couldn’t come right out and say it.”

On that night, over 60 years ago, some 73 million American viewers, many of whom children, had their first proper introduction to John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

The Beatles’ performance that night was an event far more profound than simply a memorable entertainment fixture. For some, it unlocked a realisation that aspirations were entirely possible to achieve, and that the future shape of popular culture could be dictated by young people, including themselves.

The Ed Sullivan Show appearance that February night was hotly anticipated. Finally, it gave millions the chance to actually put faces to the voices they’d begun hearing repeatedly on the radio, and to far-flung stories of international conquest circulating in the media.

“We had heard of them, but nobody had ever seen them,” recalled Ken Erlich, producer of the documentary The Night That Changed America. “It was before VCRs - it was before colour - and we were sitting there, and all of a sudden these kids came on. They didn’t really look like us, but they looked like we wanted to look, and they sang these great songs. They sounded familiar but they sounded different.”

The timing of the Ed Sullivan Show appearance was no fluke. In fact, it marked the carefully orchestrated conclusion of a deftly-steered PR campaign, overseen by hyper-perceptive manager Brian Epstein. The man who'd transformed the group from weathered, leather-clad rockers into a saleable, besuited, pop offering.

Epstein had harnessed the Beatles’ international ‘mania’ narrative to its obvious endpoint, a televised storming of the barricades that would introduce the band to a continent who could make or break the band's longevity.

Epstein had been angling to get his boys on US television for months, but the Beatles themselves had become tactical enough operators over their many years of self-governance, to realise that US momentum could be built externally, and then seized with a debut tantamount to a victory lap.

“I think one of the cheekiest things we ever did,” Paul reflected in The Beatles Anthology, “was to say to Brian Epstein, ‘We’re not going to America until we’ve got a Number One record.’”

Cheeky it might have been, but the blueprint for unprecedented fame had been drawn.

“It just seemed ridiculous - I mean, the idea of having a hit record over there,” John Lennon told Playboy a year later. “It was just something you could never do. That's what I thought, anyhow. But then I realised that kids everywhere go for the same stuff; and seeing as we'd done it in England, there's no reason why we couldn't do it in America too."

Over in Europe, the Beatles early conquests were being hurriedly reported by the at-times bemused, and other times triumphant British media. As nation after nation succumbed to the Beatles' charms, tastemakers in the US grew increasingly curious about just what power this mop-topped troupe of conquerers held.

Before long, headlines such as “Thousands of Britons Riot”, “The New Madness” and “Britons Succumb to Beatlemania” underlined the hysteria around the Beatles. But while these pieces were penned by fad-conscious, skeptical journalists, America’s youth were wide-eyed and ready.

With no access to any way of watching the band visually, many had to make do with catching a fleeting glimpse of the Beatles arriving at an airport somewhere on TV news, or fawning over static images in newspapers. There was a growing feeling from US audiences that they were being neglected.

And, they were right.

Capitol Records - the US subsidiary of the Beatles’ label, EMI - was proving an intractable issue for the Beatles' management.

Snobbishly disinterested in promoting the Fab Four, Capitol had settled early on the assumption that the Beatles, like countless other British hopefuls, would prove too unknowable - too 'British' - to win over the US market.

They had, therefore, been siphoning off the band’s earlier singles to a roster of smaller labels (Swan and Vee Jay) with minimal promotional spend.

But as international sales began to rocket, homegrown interest was heightened. Calculated pressure from Brian Epstein managed to coerce Capitol down from their stubborn position, finally relenting and agreeing to put out a freshly minted new single (tailor-made for the US market, at the behest of Brian) stateside. And, with it came a sizeable amount of promotional spend.

The timing was critical, as the Beatles had also won over Ed Sullivan - then one of the US’s key cultural tastemakers via his weekly televised variety show.

The Ed Sullivan Show was appointment, communal viewing for American households, relied upon to deliver an eclectic mix of entertainers that the entire family could get something out of.

Sullivan had witnessed Beatlemania firsthand during a trip to London in October ’63, as the four had returned from their first Swedish tour at Heathrow Airport. Sensing a potential spectacle on a par with Elvis, the judicious Sullivan was keen to secure them for his own show.

Hearing of Ed’s interest, Epstein fixed a date to meet with the titular host during that same, eventful US trip in which he’d managed to sway Capitol.

Epstein played to Ed's pride, and sold him on the event angle.

This could be the big catch. And Ed could be the one to reel it in.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Now fully courted. Sullivan booked the band on US television over three separate appearances over successive weekends. Two live, and one pre-recorded.

And, as fate would have it, the band’s own brash stipulation that they wouldn’t play America until they gained their long-hungered for number one was also met.

Fuelled by the rising sense that something big was coming, the Capitol-backed I Want to Hold Your Hand finally galloped up the US chart and into top spot the week prior to their appearance.

Everything was lined up, now was the time to strike.

And strike they did. On the night of February 9th 1964, at 8pm, the Beatles commandeered the nation’s television sets.

"Close your eyes and I’ll kiss you, tomorrow I’ll miss you", sang Paul, as the four sprang into the effervescent All My Loving. In that one line, the four working class Liverpudlians demanded, and eagerly received, the attention of the most powerful country on Earth.

While many screamed at the sheer romantic joy of it all, for the musically-minded too, the appearance was eye-opening. Surprisingly, this group, whom many had already pre-judged to be a flash in the pan, had unlocked a new way of looking at what a pop group could be.

Demonstrating remarkable musicianship across their debut song (McCartney’s kinetic bass part and Lennon’s jagged rhythmic triplets), the Beatles were comfortable musicians.

They made their quite intimidating-looking guitars seem flexible toys. Weapons which could be seized and mastered.

While to all intents and purposes, this was the band's introduction, Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr had long since earned their stripes, from the clubs of Hamburg to their years-long fixture at the Cavern.

Now, they made it all look so easy, so attainable.

Others were struck by the sheer oddness of their appearance. These weren't familiar Californian surfer dudes, or run-of-the-mill, choreographed stage performers. These were four, northern English working class boys, seemingly having the time of their lives just playing music together.

It was something for which Americans had no context. They may as well have been aliens.

But, they just couldn't take their eyes off them.

For the Beatles themselves, holding court before the 728 members of the studio audience - and some 73 million watching across the length and breadth of America, it felt like they had finally reached the summit. The place where they were always long-gaming to be; the proverbial toppermost of the poppermost.

Amongst the multitudes of television watchers that night, one Bob Dylan, who later remarked to Rolling Stone “They were doing things nobody was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid.”

After that blistering launch, their second song demonstrated their musical breadth. A cover of Broadway musical The Music Man’s Till There Was You, laid out a more intricate, sensitive and romantic side which spotlighted the group’s aptitude at translating others’ work into the Beatleverse.

During this performance, useful overlaid text introduced each member (which included the legend ‘Sorry girls, he’s married’ beneath Lennon). It all built up to the sense that this was the official ‘launch’ of the Beatles, just as Epstein had promised Sullivan.

“I was in my parents’ bedroom, huddled around our sole vacuum tube television with my two brothers, my mom, and my dad. What we saw changed everything,” recalled one viewer. "The long hair, the sharp suits, the cute well-scrubbed faces, the infectious personality, the audience of hysterical teenage girls, and the music… Oh, their magnificent music! Beatlemania, broadcast live, right in our own home.”

Following a brisk streak through their finest early single, She Loves You, a viewer-teasing pause then followed.

Sullivan had chosen to astutely break up the Beatles’ performance, gambling that this would kept the now Beatles-hooked on the line, eager for their return for the show’s stunning finale.

True to his word, the Fab Four returned to seal the deal via the kinetic workout of I Saw Her Standing There and, to climax, a victory roll through US chart-topper I Want to Hold Your Hand.

The overwhelmed hysteria of many of the young female fans, and the peculiar, staunchly un-American bowl-cut hair of the four Liverpudlians, caused some critics to sneer. Yet seeds had been sown that night that could never be unsown.

A new way into fame, and just what a successful musician could be had been revealed. A definition that would continue to be pushed ever-outwards as the band’s career evolved throughout the 1960s.

From the outset, one of the Beatles' key USPs had been that they were a creative unit who wrote their own songs, played their own instruments and, as far as anyone watching was concerned, had been the architects of their own destiny.

Lennon, McCartney, Starr and Harrison represented something different. These weren't just the hired hands of a songwriting enterprise, the attractive salesmen working for the profit-books of shadowy industry types.

The Beatles were a youth-driven creative endeavour, with a vibrant songbook that had been birthed organically from their own minds.

It's hard to express today how seismic these implications were back then. For some guitar-curious young viewers, it was tantamount to a revolution.

The showroom doors of pop music's potential as a creative medium had been opened for the first time.

“I was watching The Ed Sullivan Show and I saw them,” recalled Kiss legend Gene Simmons in the Liverpool Echo. “Those skinny little boys, kind of androgynous, with long hair like girls. It blew me away that these four boys from the middle of nowhere could make that music. Then they spoke and I thought ‘What are they talking like?’ We had never heard the Liverpool accent before. I thought that all British people spoke like the Queen.”

Charles Pfeiffer, interviewed for Garry Berman’s We’re Going to See the Beatles!, watched the performance with his family in Kansas. “On that Sunday night in February of ’64, we gathered around the black & white Zenith, and gosh, when they struck that first chord it just sent something through me. And I was a 12-or 13-year-old boy with a crew cut, and I remember I turned around and said, ‘I’m growing my hair out.’ That was the first thing I was gonna do, which I started to do. And just the minute they started to play, I thought, ‘Gosh, this is what I want to do.’”

Two days later, the buzzing foursome took a train to Washington for their first full-length US concert show at the Washington Coliseum (thankfully documented for the ages by Albert and David Maysles in their sublime time-capsule documentary, The First U.S. Visit), and would re-appear on Ed’s show later in February for their further two scheduled episodes, one live from Miami on February 13th and their pre-recorded appearance playing out on the February 23rd edition.

But, in one night, the Beatles had left a permanent footprint on American culture. Imitators would come in their thousands, and self-sufficient, songwriting-driven guitar bands became the prerequisite norm. The British Invasion had begun.

America, watching as one homogeneous entity, began a passionate love affair with four boys from Liverpool that, to this day, shows no signs of abating.

As Ringo remarked (in the Beatles Anthology), “I still have people talking about where they were that night, it’s like where were you when Kennedy was shot.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.