“The title came up as a joke at first, but it fitted the song so perfectly – we just had to use it”: How Massive Attack created the groundbreaking ’90s hit that propelled Bristol’s unique music scene into the global spotlight

“We were trying to create dance music for the head rather than the feet"

Shara Nelson was midway through recording vocals at Coach House Studios in Clifton, Bristol when the vocal melody and lyrics for the song that would become Unfinished Sympathy came to her.

It was the summer of 1990 and Nelson was guest vocalist on the debut album Blue Lines by Massive Attack, the Bristol trip-hop collective formed in 1988 and featuring Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja, Grant ‘Daddy G’ Marshall and Andrew ‘Mushroom’ Vowles.

On the day Unfinished Sympathy came into being, they had been struggling to record a track called Safe From Harm.

“I couldn’t concentrate very well,” Nelson told Uncut magazine in 2010. “So we were told to take a break, have a cup of tea.

“I didn’t drink tea at the time, so I just stood in the corner and started trying to put together this idea that had been going around my head for a while. I started mumbling to myself, half singing the lines, ‘I know that I’ve imagined love before.’ The melody and the words started to come into shape.”

In the studio with Nelson at that moment was producer Jonathan ‘Jonny Dollar’ Sharp and Andrew ‘Mushroom’ Vowles.

Nelson recalled: “Mushroom heard what I was doing and said: ‘What’s that? Sing up, girl.’ So I started to sing and Mushroom put some beats towards it and Jonny Dollar started playing synthetic strings, and that was it. It was a real rogue track.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The song, co-written by Nelson, Vowels, Del Naja, Marshall and Dollar, would become the second single on the album.

With its heart-rending vocal and sweeping strings, Unfinished Sympathy showcased a unique fusion of musical styles that were as emotive as they were chilled.

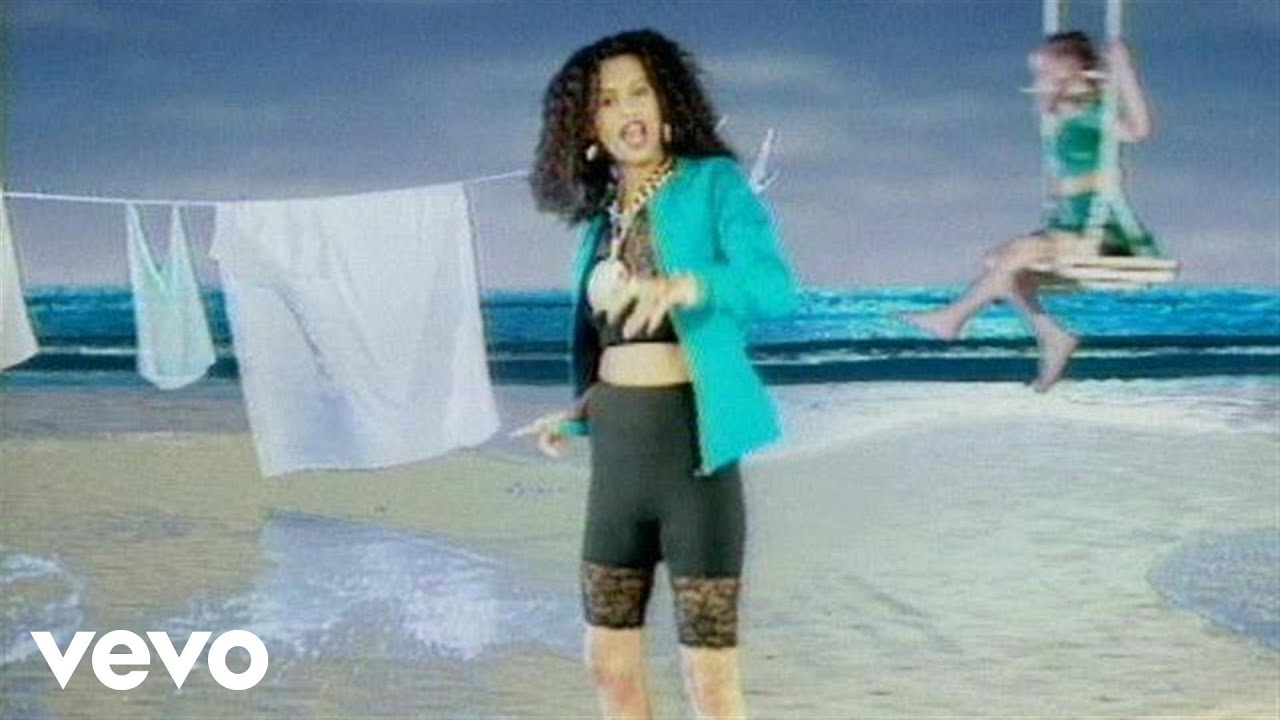

The song and the cutting-edge video that accompanied it, would propel Bristol’s unique music scene into the global spotlight.

The musical climate that forged the Bristol sound can be traced back to 2 April 1980, when police raided the Black and White Cafe in the heart of the St Pauls area of the city. The heavy-handed tactics of the police became a flashpoint, sparking a riot, fuelled by community grievances, racial tensions and the government’s controversial ‘sus’ laws.

The outpouring of anger from the St Pauls community took the police by surprise and they were soon outnumbered. In the aftermath of the riot, the police gave St Pauls a much wider berth and this created a climate where communities would come together through impromptu street parties, with custom-built sound systems.

These sound systems provided the musical backdrop to inner city Bristol and would become a unifying force for young people, regardless of their skin colour.

“Sound system culture was all about DIY,” said Roni Size in a 2016 BBC documentary Unfinished: The Making Of Massive Attack. “It was about learning how to string up amps, how to cut the wood, how to load the speakers onto the van properly, even [learning] how to drive a big HGV lorry down the narrow roads in St Pauls.”

The sound system culture shared a DIY ethos with punk and there was one seminal post-punk Bristol band, The Pop Group, that would have a huge influence on development of the Bristol sound.

The Pop Group’s sound was aggressive and avant-garde, incorporating elements of funk, free jazz, and dub. Their tours took them to New York, where they became entranced by the emerging hip-hop culture.

“We were virtually living in New York,” recalled former singer and founder Mark Stewart in the Unfinished documentary. “Suddenly, somebody says there's a really cool radio show on this thing called Kiss FM and WBLS.

“We used to have big ghetto blasters of double cassette machines back in the day. We copied these tapes, brought them back to Bristol. Copied, copied, copied.

“3D would draw on them. Suddenly, everybody was getting into hip-hop in Bristol. London was not even aware of it.”

By the mid-’80s, the Bristol scene was thriving and its epicentre was the now legendary Dugout club, in the city’s Park Row, where the Wild Bunch performed a regular slot and dominated the Bristol club scene.

In 1988, Massive Attack was created as a spin-off group from the Wild Bunch and featured Daddy G, Mushroom, 3D and, in the early days, Tricky.

3D had been a co-writer on Neneh Cherry’s song Manchild.

Along with her husband, singer, songwriter and producer Cameron McVay, Cherry would help Massive Attack to record Blue Lines, which they started work on in 1990.

“One of the things that made Massive Attack into the phenomenon they were was meeting and knowing Neneh Cherry and Cameron McVay,” said Sheryl Garratt, former editor of The Face. “They supported them financially and gave them lots of resources and really encouraged and nurtured their talent.”

Cherry also injected the drive necessary to cut through the chilled-out languor of the Bristol scene.

For all their talent, Massive Attack were not driven by ambition or any desire to be celebrities.

“We were lazy Bristol twats,” Daddy G told writer Ben Thompson of The Observer in 2004. “It was Neneh Cherry who kicked our arses and got us in the studio.

“We recorded a lot at her house, in her baby's room… what we were trying to do was create dance music for the head, rather than the feet. I think it's our freshest album, we were at our strongest then.”

By then, the sound that music journalist Andy Pemberton would define as ‘trip-hop’ in the June 1994 issue of Mixmag magazine was taking shape, a melding of New York hip-hop with homegrown dub, soul, funk, jazz and electronica, and all imbued with an achingly melancholic and laid-back feel.

This was the sound that would distinguish Blue Lines and would first come to prominence on Unfinished Sympathy, released as a single two months before the album.

“Blue Lines kind of had this impact where they recognised Bristol having a sound,” recalled Roni Size in Unfinished. “It was that underlying sub-bass from the dub. It was the breaks from hip-hop and the two gel together. It just summed up the culture and I think Massive Attack really tapped into that.”

Once Mushroom, Nelson and producer Dollar had worked up the basis of Nelson’s vocal melody and lyric, Massive Attack worked on the song during a jam session.

The song’s title, Unfinished Sympathy – a pun on Franz Schubert's 1822 Unfinished Symphony No.8 in B minor – was decided that same day.

“I hate putting a title to anything without a theme,” said Robert Del Naja in Select magazine in 1992. “The title came up as a joke at first, but it fitted the song and the arrangements so perfectly, we just had to use it.”

The song’s arrangement incorporates scratching and drum programming from Mushroom.

Chilled hip-hop beats set the tone and there is a percussion break sampled from jazz trombonist, composer and arranger JJ Johnson’s 1974 instrumental Parade Strut.

One major decision taken in the early stages of the song was to use a real orchestra on the track.

“The synth sounded too tacky,” Mushroom told writer John Robb of Sounds in 1991. “So we thought we may as well use real strings.”

Dollar contacted the music producer Wil Malone (who had worked on Iron Maiden’s debut album in 1980) to arrange and conduct the strings, which were recorded in Studio Two at Abbey Road Studios, London.

A 42-piece orchestra was hired to perform the surging string arrangement. Dollar had instructed Malone to “do what you feel like” with the string arrangement.

“My approach for Unfinished Sympathy was that it’s a really open track,” Malone told Uncut magazine. “Basically it’s just a groove – keyboards, and a great vocal by Shara Nelson – so you just let it drift, just let it chill.

“With most string arrangements that I do, the strings are ‘put back’ in the mix. In other words they are so quiet you don’t really hear them, or they’re mixed up, so that you can just hear the top lines.

“But on Unfinished Sympathy, the strings are exposed. You can really hear them and I think that makes something different.”

Vowles told John Robb of Sounds that the orchestra “were really good [but] it took them about five takes to do it because they were slightly behind the beat”.

The orchestra is a haunting and enigmatic addition to the song.

Unfortunately, as Massive Attack never set out to use a full orchestra on the album, they hadn’t budgeted for it. Mushroom had to sell his car – a Mitsubishi Shogun – to cover all the hiring costs for the orchestra.

One surprising aspect of Unfinished Sympathy is that there is no actual bassline on the original album version of the song.

The bass is provided by the orchestra.

Unfinished Sympathy was released on 11 February 1991, in the midst of the Gulf War.

On the advice of their record company and management, the group dropped the word ‘Attack’ from their name, to allegedly prevent the song being banned by the BBC, releasing the track simply as ‘Massive’.

Unfinished Sympathy was groundbreaking and hugely influential, a unique blend of electronic and orchestral elements that is both melancholic and uplifting.

The song is justifiably considered a masterpiece, one that set the template for the trip-hop genre, with its ethereal strings, dub-heavy bass and shuffling beats.

It’s a sophisticated arrangement elevated by Shara Nelson’s effortlessly emotive vocals.

Commercially, the song fared well, reaching No.13 in the UK singles chart and No.1 on the Dutch Top 40. But critically, it received widespread acclaim.

Melody Maker named Unfinished Sympathy its Single of the Year, concluding that that it would “unquestionably stand as one of the greatest soul records of all time”.

In a retrospective piece in 2005, BBC journalist Stuart Bailie later wrote that Unfinished Sympathy had “an emotional power that was hard to figure. It sounded anxious and lost. But there was a grandeur in the music also. People who came across the record became obsessed, spinning it endlessly.”

In 2012, the enduring emotional power of the song was also noted by John Bush of All Music in a retrospective review.

“Unfinished Sympathy remains one of the most elegant, sophisticated works in the history of electronic dance.” he wrote. “The emotional effect is extraordinary when coupled with Shara Nelson's searching vocal.

“A sleek, catchy drum programme and a little shadowed scratching (the only reference to their b-boy past) complete this simple, but tremendously moving, dance production, a tribute to the continuing emotional tug of great music – whether the source is organic or electronic.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.