"I remember in the studio thinking: ‘Oh my God, how am I going to deliver this to the label tomorrow?’ I’d totally lost sight of its potential": A music professor breaks down the theory behind All Saints' Pure Shores

As the William Orbit-produced Pure Shores turns 25, we put the blissful '00s hit under the musical microscope

2025 marks the 25th anniversary of All Saints’ chart-topping '00s classic Pure Shores, so let’s find out what gives the track its dream-pop magic.

Group member Shaznay Lewis and producer William Orbit wrote Pure Shores for the soundtrack to the 2000 Leonardo DiCaprio film The Beach. All Saints also included it on their second album, Saints & Sinners.

The song debuted at number one on the UK Singles Chart, and was also a major hit across Europe and Australia. It didn’t make the same kind of impression in the US, maybe because the movie didn’t do much business here either, but my friends who are fans of William Orbit appreciate it.

Orbit produced the instrumental track first, and then Lewis wrote the vocal part on top of it, referencing a clip from the film where Leonardo DiCaprio and Virginie Ledoyen swim underwater. Lewis only sings on the bridge; the lead vocals elsewhere are by fellow All Saints member Melanie Blatt, with backing vocals by the sisters Natalie and Nicole Appleton.

It’s common to combine chords from Mixolydian mode in rock and pop, but you don’t usually use these chords in this order

The tune is a simple one in its basic construction. It’s organized around a four-bar chord loop in C# Mixolydian mode: C#, D#m, B, F#. It’s common to combine chords from Mixolydian mode in rock and pop, but you don’t usually use these chords in this order. The move from D#m to B doesn’t feel like a move at all, since they are practically the same chord.

The main loop runs uninterrupted through the entire song aside from an eight bar bridge toward the end. That bridge alternates G#7 and G#7sus4, moving us temporarily from C# Mixolydian to C# major. Anyway, the song’s main interest is not in the notes. It’s in the rhythms and sounds, the dreamy vocals floating above the gently abstract electronic textures.

William Orbit is best known to Americans as the producer of Madonna’s Ray of Light album from 1998, which still sounds sleek and futuristic all these years later.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

There is not much information out there on Orbit’s production for All Saints, but we know that it was a lengthy and difficult process.

In a 2021 interview with The Guardian, Orbit recalled that the track took so long to make that he ended up thinking that it was “pure shite” - though he now has a more charitable view. “I remember in the studio thinking: ‘Oh my God, this is a turd. How am I going to deliver this to the label tomorrow?’ I’d been working on it for two months and had totally lost sight of its potential,” he later told Classic Pop.

Though the details of the production behind Pure Shores aren’t well-documented, Orbit’s work on Ray of Light was, and it’s fair to assume that he will have used some of the same gear and techniques.

He explains his process on Ray of Light in a Keyboard Magazine interview from 1998: "It's not a ton of gear. Most of it is pretty retro: a Korg MS-20, a [Roland] Juno-106, a [Roland] JD-800. Much of the album was done on a Juno-106. You can get so much out of that synth.

"Also a significant amount of it was done on the MS-20 - the more spiky sounds. A few things that people think are guitar are actually the MS-20. And then there were a few more bits and pieces: a few modules, a Yamaha DX7, a Novation Bass Station, a [Roland] JP-8000, a lot of Roland stuff. I've always liked Roland stuff."

William Orbit: "Pro Tools is a lot better than drugs, that's for sure!"

Orbit confesses that he is not much of a keyboard player, that he is a “two-fingered virtuoso” who marks up the keys with wax pencils. He uses sequencers, but he doesn’t quantize everything, preferring to combine quantized and unquantized rhythms. He also likes to record the output of his samplers and synths to tape, and then take new samples from the tape and manipulate them further. The multiple trips through the sampler, the compressor, the mixer, the tape and the sampler again creates a desirable sonic grunginess.

Orbit sequenced Ray of Light on Atari ST using an early version of Cubase, which was a pretty primitive setup even by 1998 standards. After watching Marius DeVries of Massive Attack putting tracks together in Pro Tools, Orbit was impressed and switched over to it by the time he worked with All Saints.

The most interesting production touch on Pure Shores is the organ riff, with its distinctively groovy rhythm. It enters in the first second of the intro, and continues through most of the rest of the track.

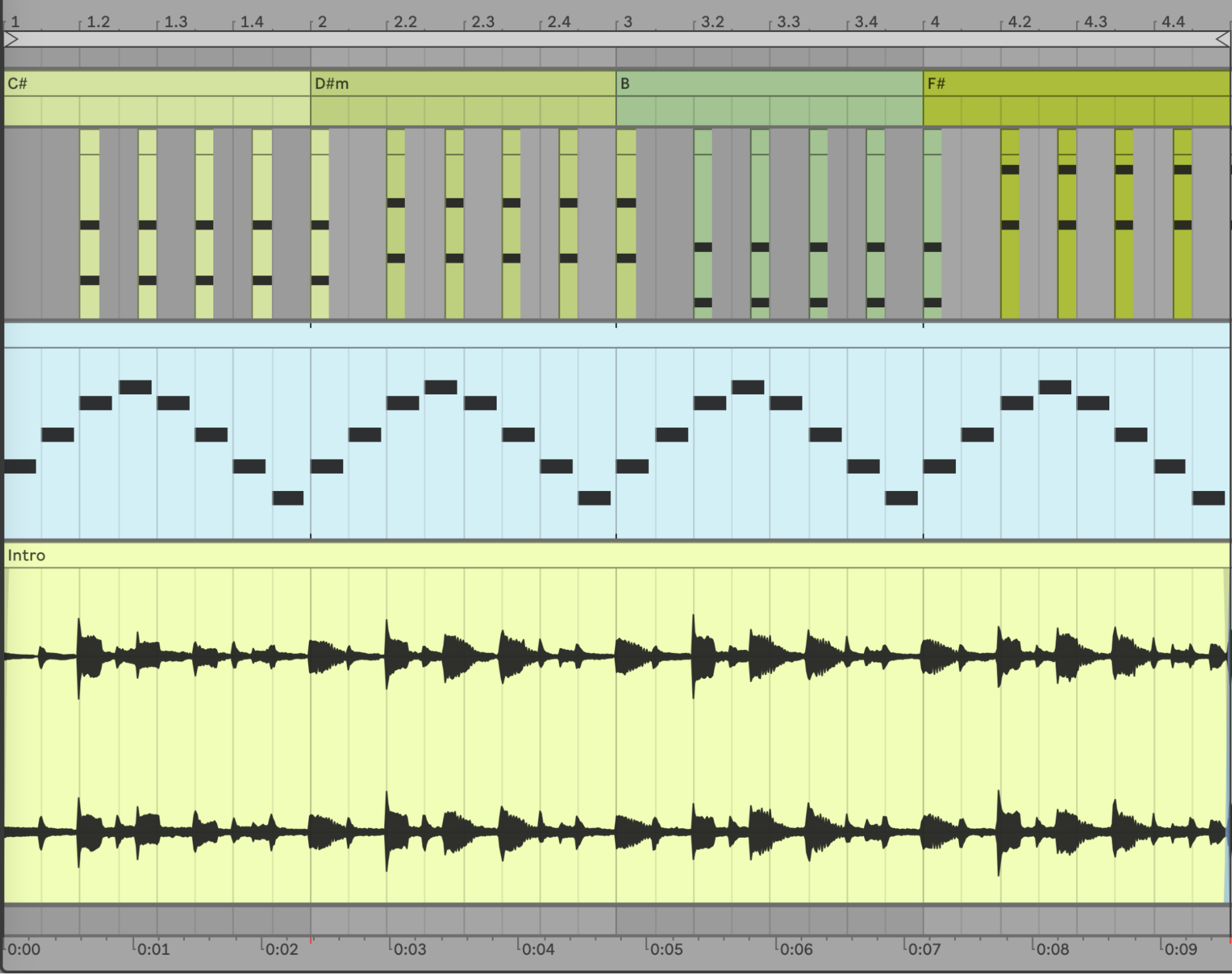

To help you understand how it works, I reconstructed the organ and “guitar” parts in the intro in Ableton Live. (I put “guitar” in quotes because it’s probably a synth.) In the image below, the organ chords are on top in green, and the guitar part underneath is in blue.

The guitar part is simpler. It runs up and down C# Mixolydian mode from C-sharp up to G-sharp and then back down to B in a steady stream of eighth notes. It does this without regard for the chords as they go by. Everything in Mixolydian more or less works with everything else, so there aren’t any jarring dissonances, but you also don’t get a sense that the harmony is functioning or progressing.

The organ plays the root and fifth of the chords. The final echo of each chord is on the downbeat of the following measure, where the chord is supposed to change. When the bass enters, it changes chords on the downbeats, so the organ gently conflicts with it, adding to the harmony’s drifting quality.

The organ riff’s main interest is that rhythm. It enters on the second beat of each bar, and then repeats every three sixteenth notes (so, every three quarters of a beat.) Because the rest of the track is organized around patterns of two or four or eight sixteenth notes, the organ moves in and out of phase, creating a hypnotic polymeter. William Orbit was obviously proud of this idea, because he also used it in Madonna’s Frozen, the first single from Ray of Light.

You can hear how much of Shaznay Lewis’ vocal melody was inspired by the organ riff. Each phrase in the verse melody starts on beat two, and the other main notes line up with the organ riff too.

The chorus melody doesn’t align with the organ riff so closely; the phrases start on beat four and the “and” of beat one. But less-important syllables still fall on organ stabs, so the alignment never disappears completely.

The idea of overlaying groups of three time units onto a background of groups of two or four is a core feature of Anglo-American popular music of every kind, especially the funky/groovy styles. The more three-against-two there is, the funkier the music. The musicologist Richard Cohn explores this idea in his article A Platonic Model of Funky Rhythms.

"African-diasporic and popular repertories commonly stretch a series of three-unit, or 'dotted,' spans across a pure-duple frame, inducing pulse conflicts at one or more metric levels. The terms associated with this class of rhythms include tresillo (Cuba), bossa nova (Brazil), secondary rag (American ragtime), and second-line rhythm (New Orleans).

"When these durational patterns repeat cyclically over extended spans of time, as ostinati, they are among the core conveyors of a song’s identity, feel, or groove. They also arise more transiently, often at moments that listeners identify as hooks."

Cohn is right about three-against-two being a feature of hooks. Consider We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together by Taylor Swift.

Most of the song’s components are two or four or eight time units long. However, the phrase “never ever ever” in the chorus is in groups of three sixteenth notes, and it is no accident that it’s the energetic peak of the song, the part that really stays with you.

Richard Cohn points out some iconic tunes that use longer chains of three against two. One of them is It Don’t Mean a Thing (if It Ain’t Got That Swing) by Duke Ellington, first recorded in 1932.

Listen to the “doo-wah doo-wah doo-wah doo-wah” riff in the horns at 0:52. Each doo-wah is a one and a half beats long, and they go in and out of phase with the underlying quarter-note pulse. At the end of the tune, the horns play the doo-wah riff unaccompanied, and you quickly lose your sense of orientation in the main quarter-note pulse. It’s a cool effect.

Richard Cohn points to an even longer chain of three-unit phrases against a two-unit backing in Ain’t No Sunshine by Bill Withers. Listen to the “I know I know I know” part at 0:50.

Cohn calls this “a twenty-six fold trochaic spooling… stretching a dotted-eighth pulse across five slow measures of pure-duple frame.” You don’t need to understand the technical language to know that something cool is happening. Just tap out the three eighth notes in each “I know” against Al Jackson Jr’s steady sixteenth-note pulse.

The conventional way to understand a syncopated rhythm like the Pure Shores organ riff is to imagine a simplified version all on strong beats, and then displace the notes earlier or later.

However, Richard Cohn points out that this is not a helpful way to conceptualize a three-against-two groove. Are those organ stabs coming earlier or later than they are “supposed” to? It isn’t really either. It’s better to think of three against two as the most basic, fundamental form of the rhythm.

Once you are listening for three-against-two polymeter, you will hear it in the coolest parts of many songs that you love. In Pure Shores, the polymeter is right up front, and together with the drifting harmonies and abstract textures, it’s no wonder that the groove is so vast and oceanic.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Madonna - Ray Of Light (Official Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/x3ov9USxVxY/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Madonna - Frozen (Official Video) [HD] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/XS088Opj9o0/maxresdefault.jpg)