“If you’re given the choice between boxing kangaroos and John Lennon you choose John Lennon”: The strange, brief existence of the John Lennon-fronted supergroup hidden for decades

Back in 1968, Lennon, Keith Richards and an unlikely collection of musical cohorts tore through a White Album highlight

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Who’d be in your ultimate rock and roll supergroup? If you’re anything like us, there’d be at least one Beatle in the mix. But for John Lennon himself, when similarly tasked with putting together a collection of players to back him up for his appearance in the Rolling Stones’ ill-fated 1968 television special, Lennon looked toward some of the era’s most proficient players

Conceived as a vibrant musical celebration, the Rolling Stones' Rock and Roll Circus awkwardly dabbled in the aesthetics of the current psychedelia-meets-Victoriana trend, yet was brimming over with a sublime array of talent.

It was dreamt up and directed by visionary, music-centric filmmaker Michael Lindsay-Hogg. He was the man who would very shortly oversee the making of the Beatles’ Let it Be film. The footage of which would ultimately form the basis of 2021's Get Back documentary series.

Lindsay-Hogg had previously directed the Stones during television appearances of British pop cultural staple Ready Steady Go!

Always a joy to work with, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and co had continued to lean on Lindsay-Hogg, entrusting him with handling promo clips (essentially prototype music videos) for Jumpin’ Jack Flash and its B-side, Child Of the Moon earlier in 1968.

But, nearing the end of the year, the Stones were keen to tap deeper into a more cinematic world which their rivals, the Beatles had successfully scaled.

When asked about the origin of Rock and Roll Circus, Lindsay-Hoog told Rock Cellar Magazine that, “I think the genesis was that the Beatles had done Magical Mystery Tour. But it was not that the Stones wanted to copy what the Beatles did in any way - they didn’t want to copy the Beatles because the Stones were The Stones and the Beatles were The Beatles, but the Beatles set an example,” Michael said.

“They [The Beatles] laid down a big footprint of how to go ahead with your career. Although [Rolling Stones’ legendary manager] Andrew Loog Oldham was out of the picture by the time came to do the Rock and Roll Circus, he was always trying to get them to do a movie.”

The idea for the special, which sported a $50,000 budget, was simple. Underneath a faux big top (erected within a sound stage at Intertel Studios in Wembley, London) an invited audience of Rolling Stones fans would bear witness to, ostensibly, a rotating mini-festival.

An assortment of artists would perform songs, culminating in the Rolling Stones themselves delivering a selection of cuts from Beggars Banquet - their upcoming seventh record. It was a release that they were keen to mark. Once edited, the show was planned to be broadcast on the BBC.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Michael Lindsay-Hogg is a very creative guy,” Mick Jagger reflected years later. “We came up with this idea and the whole idea, obviously, is to make it a mixture of different music acts and circus acts, taking it out of the normal and making it slightly surreal, mixing the two up. And also we wanted as many different kinds of music as possible. So that’s why we thought about who would be the best kind of supporting acts.”

Among the guests the Stones recruited for the show were a young Jethro Tull (featuring future Black Sabbath legend Tony Iommi), Marianne Faithfull, The Who and influential bluesman Taj Mahal. Although Cream and Traffic were invited to appear, the former had already announced their split, and the latter would soon follow suit a few months later.

The film was really built around the idea that the Rolling Stones themselves would be the star draw. They were the headliners, and the host band to which all the other performers would pay homage.

Therefore, although they were on good terms, they knew that including the then-biggest band in the world on the bill would take the wind out of their sails somewhat. “They thought if they had the Beatles on the show then the Beatles would be the tsunami and the Rolling Stones would the high tide, you know?,” said Michael Lindsay-Hogg.

But John Lennon, was increasingly being drawn to projects outside of the Beatle-verse.

Buoyed by his own latest batch of songs which he’d penned and recorded for the Beatles’ 1968 double-album (aka the White Album), he was keen to start playing with a wider family of other musicians.

Speaking to both Michael Lindsay-Hogg and Mick Jagger over the phone, Lennon was excited at the prospect of participating. After all, Mick Jagger had appeared in the studio audience to mark the live television broadcast of the Beatles' All You Need is Love the previous year. This would very much a be a returning of the favour.

There was one snag, Lennon didn’t (yet) have a solo band.

Easy, thought Jagger. Why not form a supergroup?

The suggestion instantly brought his good pal Eric Clapton to mind, whom he’d recently been jamming with with after joining the Beatles in the studio to track the wiry, pained leads of George Harrison's While My Guitar Gently Weeps.

With Cream set to tie up their loose ends shortly (with their final farewell concerts taking place the month prior to filming) he knew that Eric would be free, and expected him to be up for the gig.

As suspected, an eager Clapton said yes on the spot.

Behind the kit, none other than flexible Jimi Hendrix Experience drummer Mitch Mitchell. Mitchell was held in huge regard, and was an adept sticksman to boot. He leapt at the chance to head up kit duties for the Beatle and his new band.

One slot remained vacant. The bassist.

“Well, I think Keith [Richards] would like to do that,” Mick offered.

It was of course a given that Lennon's soon to be wife, Yoko Ono, would also be a key creative participant.

Ever the joker, Lennon’s name for this new outfit was a characteristically cheeky one: The Dirty Mac.

Either a dig at the rising blues pop trailblazers Fleetwood Mac or Paul McCartney (depending on who you ask), the Dirty Mac would have a limited, one night-lifespan.

This performance would mark Lennon’s first live performance outside of the Beatles who had, of course, stopped touring to focus on studio work in 1966.

Though rehearsals took place between the 6th and 8th of December at the Marquee Club and Olympic Sound Studios, Lennon only joined the flurry of pre-production the following day for a (rather hilarious looking) photo shoot.

According to Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Lennon arrived to rehearse for the show with Eric, Mitch and Keith on the morning of the special’s filming (December 11th) at Intertel Studio at 10am. All seasoned players, the four clicked together easily.

Lindsay-Hogg’s plan was to get the whole show in the can in one whistle-stop day, however due to a number of unexpected delays between acts, the filming process would extend until 5am the following morning.

The assembled, enthusiastic crowd consisted of fans from the Rolling Stones’ fan club alongside dancers hand-selected from London’s clubs

Beyond the musicians themselves, and to emphasise the circus-theme, there were a gaggle of performers from Sir Robert Fossett’s Circus, which included fire-eaters, trapeze artists, a medley of clowns and even, controversially, some live animals.

“The circus people brought various things which they thought we’d like,” Lindsay-Hogg told Rock Cellar Magazine. “It was in the morning and John was there with Yoko and his son Julian and I think Eric Clapton was there. We were auditioning boxing kangaroos. These are kangaroos who stood up on their back legs and wore boxing gloves and boxed."

Michael continued, “Yoko came up to me afterwards and said, ‘If the boxing kangaroos are in the show John won’t be in it,’ ‘cause she thought it was a cruel act. If you’re given the choice between boxing kangaroos and John Lennon you choose John Lennon. I don’t know if she talked to John about it; it may have been something that she thought. But she sort of spoke for him in many ways as well. Anyway, we didn’t have the boxing kangaroos, but we did have John and the others.”

The two songs the Dirty Mac settled on were rehearsed backstage and a few times on-stage that morning. The first was the Beatles’ Yer Blues. Lennon's slick 12-bar blues juggernaut had been one of his personal highlights from the White Album (which was released just one month prior). To follow, a freeform bluesy jam the four had hurriedly rustled up entitled 'Whole Lotta Yoko'.

With their slot approaching, Mick Jagger mock-interviewed John Lennon (aka ’Winston Thigh-Leg’) on camera, before Lennon stepped up to join his Dirty Mac bandmates.

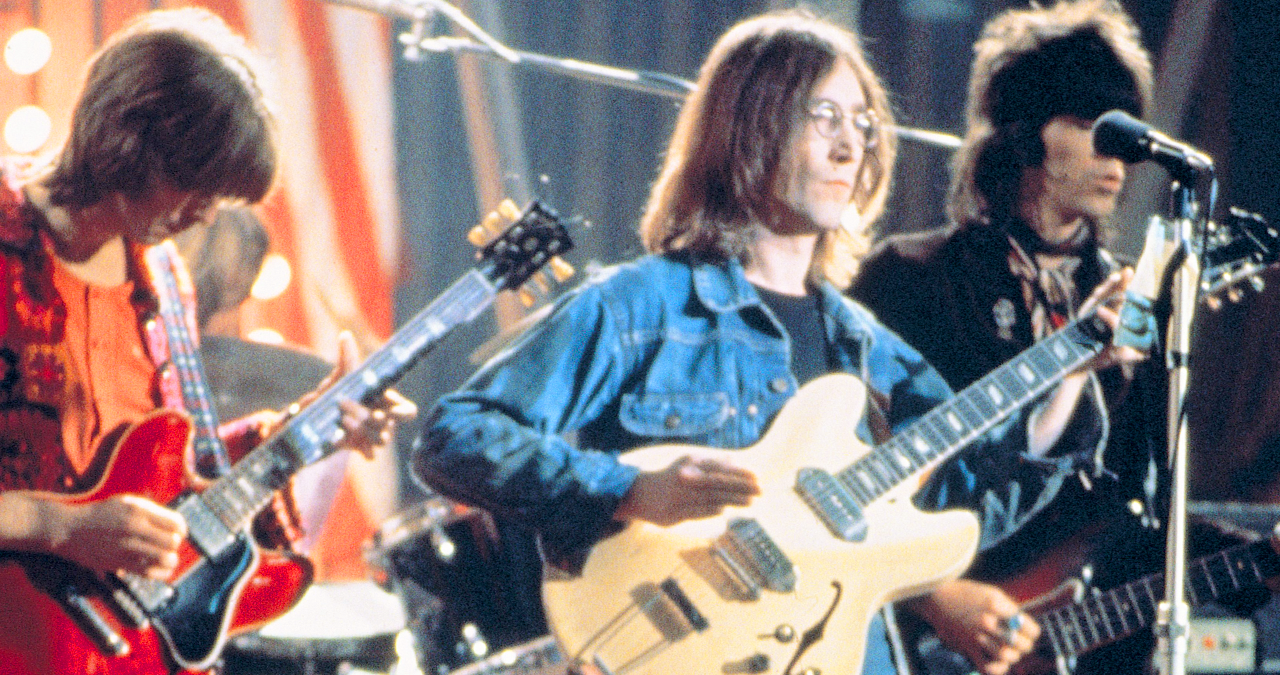

The Dirty Mac had arrived, like a mayfly, for one brief moment. And it was astonishing.

The four musicians delivered an exhilarating, dynamic rendition of Yer Blues which captured Lennon in superb voice, meanwhile the breakneck speed of Eric Clapton's fingers wrung out every possible lead route possible. The exemplary, impactful drumming of Mitch Mitchell ably supported the sultry, sludgy bass of Keith Richards. Here was the raw sound of the cream of the era’s musical heavyweights coming together.

Following Yer Blues, the band dove into the extended semi-improvised ’ Whole Lotta Yoko’, which featured Lennon’s vocally expressive partner on lead vox alongside spritely violinist Ivory Gitlis. Though this piece was much looser, the noticeable tightness of the core band is still remarkable. Very impressive, considering their brief rehearsal time.

Sadly, the Dirty Mac's thrilling two-song set would not be witnessed by anyone outside of that studio for another 28 years.

Feeling their own performance (captured during the early hours!) was sub-par, the Rolling Stones opted to shelve the entire film and pull it from its planned broadcast schedule.

The higher quality of the other musicians (particularly an astounding version of A Quick One, While He's Away from the Who earlier in the day) has been said to have been a factor. After all, the Stones' didn't want to be upstaged.

This decision proved a sad one for many reasons. The Rolling Stones’ performances themselves are actually great, and the resulting effect of canning the film meant the Dirty Mac's day in the sun would remain unseen for many, many years.

Even more sadly, this would be the final appearance of Brian Jones playing with the Rolling Stones prior to his untimely death seven months later.

Clapton would play again with Lennon at the Toronto Rock and Roll Revival in September the following year, and recorded lead guitar on Lennon’s anguished solo single Cold Turkey. But, alas, this would be the Dirty Mac’s first, and last ride.

Thought lost to history for many years, thankfully, nearly thirty years later, the 32 original film canisters which contained Lindsay-Hogg's show were re-discovered in the barn of former Stones' pianist Ian Stewart, and the world could finally witness this bewitching, semi-mythical performance for the very first time when it was released on VHS and DVD in 1996 and 2004 respectively.

"I would like it to remain not only as a great rock and roll show but also as a really insightful document about the times," said Michael Lindsay-Hogg. "There were all these talented people and they were all in a room together."

"The first time I performed without The Beatles for years was the Rock And Roll Circus, and it was great to be on stage with Eric and Keith Richards and a different noise coming out behind me," Lennon later remarked. "Even though I was still singing and playing the same style. I thought: 'Wow! It’s fun with other people'.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![The Dirty Mac - Yer Blues (Official Video) [4K] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/JeFwaWFTGYU/maxresdefault.jpg)