“They had the arrangement and I went, ‘Oh, this is finally my David Gilmour moment.’ The hair on my arms stood up”: Keith Scott on the making of Bryan Adams’ (Everything I Do) I Do It For You – the record-breaking hit no one saw coming

Scott remembers how a “plaintive melody” from Michael Kamen intrigued Mutt Lange and was shaped into Bryan Adams' biggest, hit, giving Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves the anthem it needed

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It lasted not weeks but months and it seemed like years, as though an entire era of popular music was dominated by one song. From July to October 1991, the UK charts, and the radio that shaped them, was conquered by (Everything I Do) I Do It For You, the unstopppable Bryan Adams power ballad from the box office hit Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves.

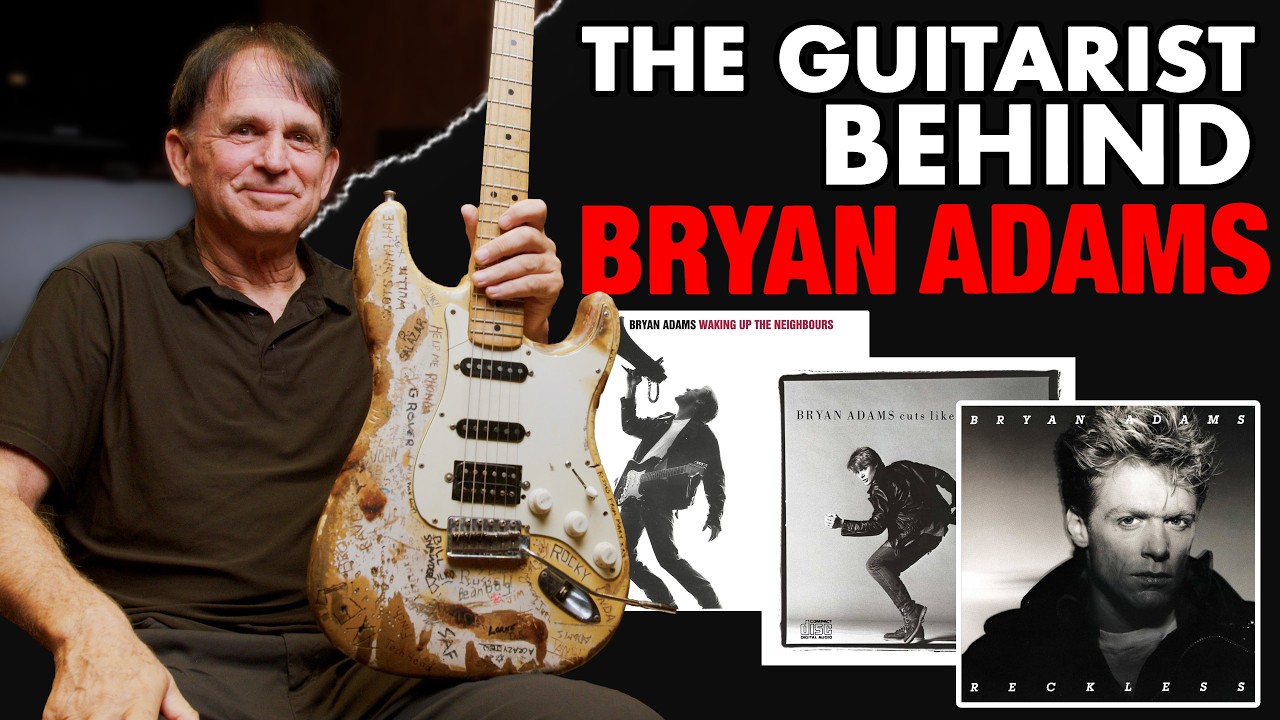

The single sold more than 15 million copies, and to think the song came together almost as an afterthought. That’s how Keith Scott, Bryan Adams long-serving guitarist remembers it.

In a recent YouTube interview with Vertex Effects’ Mason Marangella – an epic, must-see conversation for Adams fans – Scott recalls that the song started in the most unassuming fashion. Michael Kamen recorded himself whistling a melody over some keys and sent the tape to Team Adams.

The legendary Mutt Lange was skippering production on Adams’ sixth studio album, Waking Up The Neighbours, and it was progressing nicely. Scott says they were nearly done when Kamen’s tape reached them.

“Things kind of drop into your lap at times, and this song specifically, we were finishing up in North London. We moved out of Mutt’s house studio into the Battery Studios up in Willesden, and I think we were coming near the end of the overdub guitar part,” says Scott. “A cassette came in from Michael Kamen; terrific songwriter, musician and composer in every respect, film you television, you name it.

“He sent about 30 seconds of music on a cassette, and it was him playing on his little home keyboard, on a piano sound or something, and whistling a melody [Whistles]. That was it. And Brian went, ‘Well, what are we gonna do with that!?’”

Lange had some ideas. He could hear the potential in Kamen’s melody, where the electric guitar might fit in. When the band broke up on the Friday, Lange took some time to work on it.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It really wasn’t on our radar, as far as, ‘Okay, this will be a real big contender for our record

“Mutt said, ‘Mmm, it’s a pretty plaintive melody.’ I remember him saying that,” says Scott. By the time Monday came around, Lange had something, and Adams had the building blocks of a hit. Not that anyone had any idea of how big it would be – even when it started to take shape. Think about it. Waking Up The Neighbours is aptly named. It has its share of up-tempo rockers. Where did this mournful ballad fit in? Scott admits that he was just not feeling it.

“For me personally – because compared to the other songs, which were full-on like AC/DC, some of it – this song didn’t make a lot of sense,” says Scott. “But history proves otherwise.”

This is one of the leitmotifs of Scott’s conversation with Marangella – with many of his conversations with some of the session aces behind pop and rock’s biggest tracks – that no one in the studio could say for sure that it was going to connect with the public.

“Obviously with a song like that it, had its own sort of destiny. We had no idea,” says Scott. “It came in at the very end of the Waking Up The Neighbours sessions as a possible movie choice, so it really wasn’t on our radar, as far as, ‘Okay, this will be a real big contender for our record.’

“If you look at that song compared to the sound of the other the rest of the songs, it just has no context whatsoever – it’s so different. But this is the thing, and I think one of the things you questioned me about earlier was, ‘Do you have any idea what is a hit or isn’t?’ No. Who does? There’s no way to know.”

In the case of Everything I Do, there was even a movie to help spread it far and wide, but even so, this was another case in which the principals were too close to the material to think clearly about how it is going to connect with an audience. Scott believes its success helped Adams negotiate a tough time for hard rock and pop as Nirvana's Nevermind changed the cultural zeitgeist.

The movie connection certainly came in handy when they were writing it. The music wasn’t hard work. Scott says the song “kind of just assembled itself”. But the Prince Of Thieves script helped them get the lyrics together and get the whole thing done in the week.

“We tracked that really quickly, certainly in Mutt Lange terms. The premise of it was pretty quick, but they still had to write the lyrics,” says Scott. “They used the script that they had a copy of. They were pretty fast, specifically Mutt. Once he got on the train, here was no looking back. He would go for it, and still does today.”

The script would also come in handy when it came time for Scott to track the solo. Here, he has some good advice for any session player about to approach a solo. Look at the lyrics first. They’ll tell you what sort of emotion you need.

“A lot of people say, always listen to the lyric before you go in and try something because it’ll give you insight into what emotion hopefully is required, and sometimes it comes out of the sky,” he says. “More often than not, and it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m just standing here and it’s coming through me here.”

The track had everything Scott had been waiting for. Once he heard it put together, and saw how much open space he had to work with for the solo, his eyes lit up.

“I heard it back. They had the arrangement, and I went, ‘Oh, this is finally my David Gilmour moment.’ You could just hear that kind of sentiment there, you know that end of Comfortably Numb,” says Scott. “ It was like, ‘Oh, this is gonna be so fun.’ The hair on my arms stood up listening back to the open space that I was hopefully going to be afforded to do something.”

“We literally sat there and Mutt said, ‘Away you go!’ The first lick, which is the D to this to the E note, which becomes the major seventh of the four chord, and it was a total accident Somethings just fall into place and you don’t know why you do them, and it’s just amazing.”

Lange sang the next part of the solo. Then Adams joined in, singing out what the guitar solo should be. “We all chipped in,” says Scott. “And then 15, 20 minutes [later], we had a sketch, and then I just played it a whole bunch of times.”

Scott says working on Waking Up The Neighbours with Lange challenged him to adjust his playing. Lange still thought the solo needed something else. He wanted Scott to work the whammy bar more towards the climax of the solo. In the end, all of these little details add up.

I came in with more of a bluesy Clapton sort of vibrato, you know – that was kind of my background. But I think Mutt was hearing a quicker tremolo

“That was Mutt,” says Scott. “I came in with more of a bluesy Clapton sort of vibrato, you know – that was kind of my background. But I think he was hearing a quicker tremolo, and he loved, like, David Lindley with a slide, and things like that, really rapid.

“A a lot of the solos on that first record was me with a trem trying to make a faster shake to it. It just made more of a statement with the music, and I had to adjust to that a little bit, along with a whole bunch of other things with how I played.”

Scott tracked it on Adams’ 1962 Fender Stratocaster through a Vox tube amp. He had a Pete Cornish treble booster and a Soft Sustain boost/compressor pedal for the sessions. The Strat was a keeper.

“His has a certain midrange to it that especially Mutt really liked,” says Scott. The Strat was perfect for Scott’s hybrid picking style, where he would use his fingers on the lower notes to give them “more of a vocal quality”.

But Lange has a thing about Strats. When the treble booster is working the amp hard, that overdriven sound has a harshness circa 2000Hz that needs dialled out.

“We spent a lot of time with a notch filter on the console, and you basically just play a bunch of stuff, and Mutt would listen back and notch it out,” says Scott. “You wouldn’t really notice because it was so narrow. It was something like 1980 cycles or whatever. We always were able to do that.

“Because there’s a harshness to it, it really interferes with other sounds. Everything is in the same register – the voice, the snare drum, the guitars, drums – and they are all vying for the same space, especially the vocalist.

“You do not want to interrupt that when you are working with a singer, so this was one of the problems with the guitar that we used on all those sessions. We always had to notch that nastiness out.”

(Everything I Do) I Do It For You needed to be done quickly. There was no time for multiple takes. The movie’s production team needed the track as soon as possible.

But there was still time for Scott to get his Hollywood ending, playing the song out with a second – and extended solo – that would be just the thing as the credits rolled.

“I think because it was for a film, maybe they thought when people were in the film theatre and they’re leaving, the credits are going and they’re sweeping up the popcorn, they want the song to trail off, so you just keep playing, and they just tacked on a bunch of stuff at the end. ‘Away you go, kid! …Do your thing, kid!’ I had a lot of fun.”

You can watch the full interview with Keith Scott – plus conversations with Dann Huff, Lee Ritenour and more – at Vertex Effects YouTube channel.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.