“Marc is criminally underrated as a guitarist. All rock ’n’ rollers love T. Rex, and there’s a little bit of T. Rex in every rock ’n’ roll band”: When T. Rex opened the floodgates of glam rock with the riff-driven groove of Get It On

T. Rex's signature song was written and recorded while on a hectic US tour, and would be their only stateside hit

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

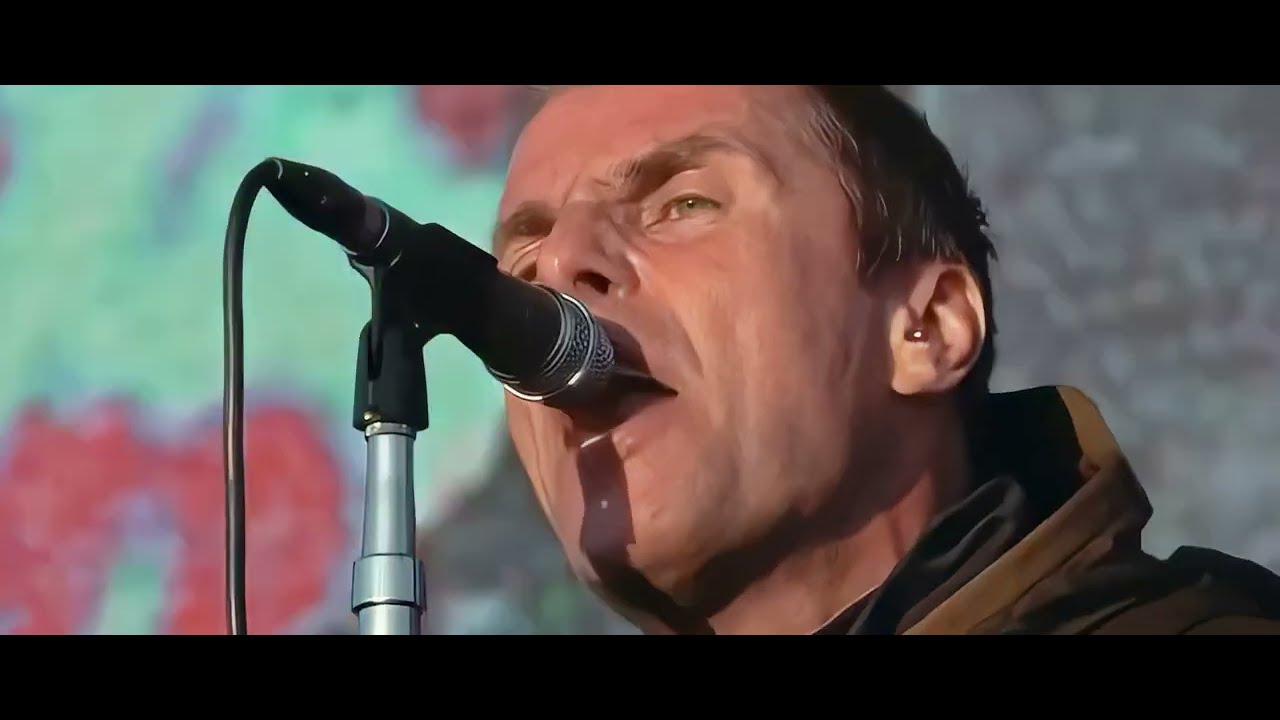

One of the most memorable moments during the world tour undertook by the resurrected Oasis this year, has been the anticipation-stoking, nightly ritual where Liam Gallagher commanded the tens of thousands of assembled fans to turn away from the stage, put their arms on the shoulders of the people next to them, and bounce in unison to the growing, growling chug of the central riff of their 1994 monster, Cigarettes & Alcohol.

Also known as the ‘Poznań’ (after a traditional backwards-facing football celebration), this ritual of connectivity is locked tightly to the retro-flavoured rock 'n' roll groove defined its bluesy E-major-pentatonic riff.

It's a riff that seems to peel back to the skeletal blueprint of just what rock music is; a reminder of the raw promise of pop music as salvation from a life - as dictated by Cigarettes & Alcohol’s lyric - where there’s nothing worth working for.

But that riff isn’t just some vaguely sketched ghost of a more optimistic age, the familiarity of that riff stems from a very specific origin.

As Noel Gallagher was well aware, just a little over twenty years prior to the release of that Oasis single, a riff almost identical to it was deployed to propel one of Britain's most era-defining acts into the pantheon of rock legend.

With it, they scaled the summit of that same UK chart that Oasis were hungrily eyeing.

“I remember going down to the rehearsal room with this song and Bonehead used to always be the tut-tutter,” Noel Gallagher recalled back in an interview for Oasis’ 2006 compilation Stop The Clocks. “I went ‘I’ve got this tune called Cigarettes & Alcohol’ and he does his tut-tut and then I did the riff and he went ‘Whoa, you can’t do that, that’s T. Rex’ and I was like, ‘I don’t give a s**t who it is, no-one’s gonna hear it anyway’.

By leaning into that particular riff, Noel was deliberately cribbing from the halcyon explosion of British glam rock, spearheaded by T. Rex and cemented by their totemic transatlantic smash, Get It On.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It wasn’t the only success story from the British pop music bible that Noel would mine from when penning Oasis’ run of hit mid-1990s singles… but it’s that T. Rex triumph that we’re here to look deeper at today.

Colliding past, present and future, T. Rex in 1971 almost single-handedly built a new chart-friendly context for rock in the wake of the Beatles' abdication.

T. Rex's take on the rock ’n’ roll form stripped away the machismo and underlying air of threat then exuded by their denim-clad, electric blues contemporaries.

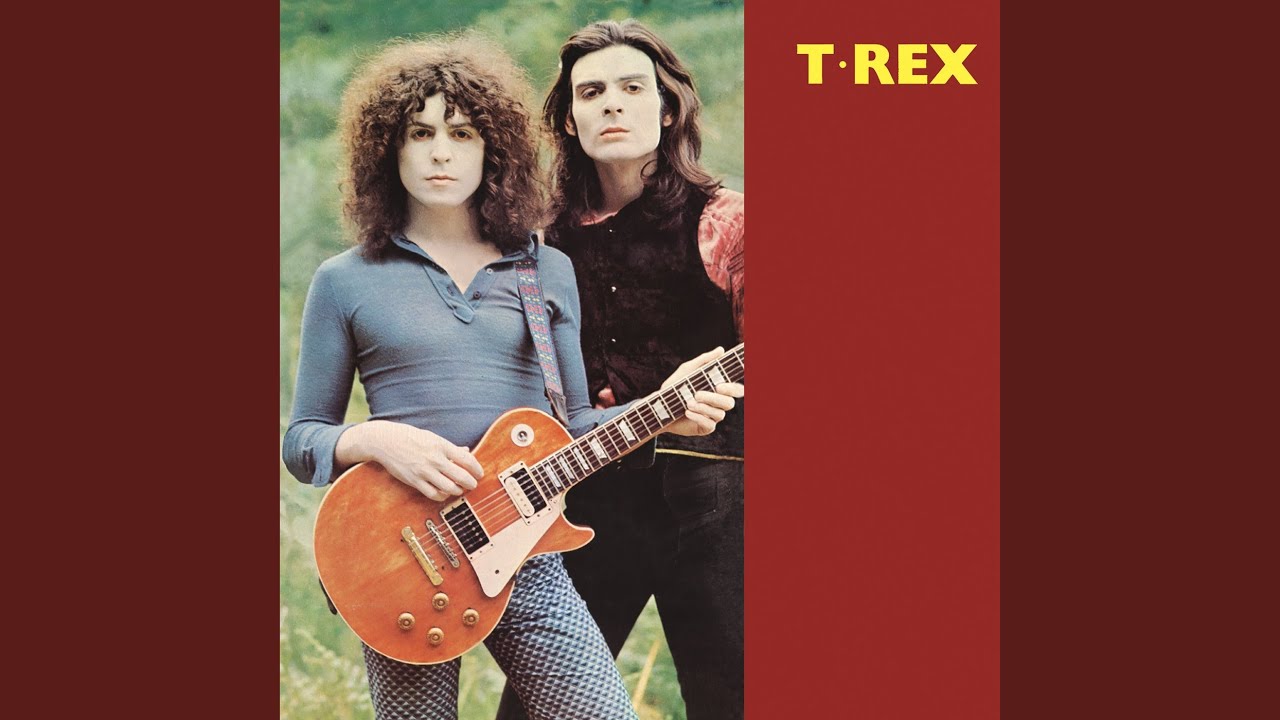

Led by the Pied Piper-like figure of Marc Bolan, T. Rex’s music coupled infectious hooks with exhilarating rock riff-age and dense musical arrangements, helmed by longtime producer Tony Visconti.

As sub-genres began to splinter music fans into myriad warring tribes during the early seventies, T. Rex lay firm claim to the centre ground.

Into this verdant new mainstream pasture came the more cerebral, art-rock futurism of Roxy Music while on the other-end of glam rock's Venn diagram, came the trashier stomp of The Sweet and Slade. It was also a moment in Britain's ever-shifting pop narrative that would usher in David Bowie’s most celebrated incarnation, Ziggy Stardust.

But in the beginning, there was Marc.

“It’s always nice to be looked on as some kind of innovator,” Bolan reflected to NME a few years on from the dawn of glam. “If it hadn’t been me, it would have been somebody else. Look man, when that whole thing happened, visually the whole scene was a bit dead. I just brought back the weirdos.”

Initially dubbed Tyrannosaurus Rex upon forming back in 1967, London-born singer/songwriter Marc Bolan (real name Mark Feld) and percussionist co-star Steve Peregrine Took (later replaced by Mickey Finn) landed on a limited form of success as a duo with a knack for penning acoustic-driven ditties that swam deep within the rivers of fantasy and whimsy.

On early LPs, My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair…, Prophets, Seers & Sages and Unicorn, the activities of druids, fairies, wizards and occult rituals were regular topics of concern for the throng of Bolan's devotees, but the rest of the world weren't listening.

The most famous of Tyrannosaurus Rex's devoted fanbase was influential BBC radio DJ John Peel, who championed Bolan and instructed listeners to indulge in his idyllic visions of a magic-infused Britain seemingly tacked-on to a map of Middle Earth.

“They had a very limited audience, who were mostly John Peel fans,” Tony Visconti, the producer of the majority of Bolan's records, recalled to The Guardian in 2015. “They wanted the most underground thing going and they wanted to preciously hang on to that. We know how many of those people there were: it was 20,000. We always hit the ceiling at 20,000 album sales.”

Dissatisfied with this seeming ring-fence around their fame, Bolan was increasingly pondering how the band could build their profile, whilst also maintaining their mystical spirit.

Purchasing a white Fender Stratocaster (decorated with a paisley teardrop motif) from his friend, Pink Floyd's then-frontman Syd Barrett, Bolan began to slowly incorporate more rock ’n’ roll-leaning licks and riffs into the material found on fourth LP, A Beard of Stars and the first eponymous record of the rechristened T. Rex.

With the growing prominence of electric guitar, T. Rex would undertake the most unexpected of revolutions, digging themselves out of their self-imposed Hobbit-hole and exploding into the public consciousness.

These initial folk and blues rock-blurring efforts would crystallise with the incredible Ride a White Swan.

This strange little song was repetitious, driving itself into listeners' heads with lyrics performed as if they were some wizard's incantation, but the song was underpinned with a loose, electric guitar-hinging swagger

It was the moment of regeneration, enmeshing Bolan's cuddly pastoral fantasy with his newfound chops for classic rock 'n' roll.

Though initially entering the lower reaches of the chart, Ride a White Swan would slowly seep its way into homes via continual radio play. It was a mantra that, to the surprise of everyone, bewitched a nation.

Before long, it was number 2 in the British chart, and Bolan was sure he'd hit upon a recipe for success.

In the newly christened outfit were Steve Currie on bass, Bill Legend on drums and Mickey Finn on percussion, and the next T. Rex hit would firmly cement Bolan as the heir apparent of British pop's crown.

Even more than Ride a White Swan, Hot Love presented T. Rex's new modus operandi in a little under five minutes.

Into the cauldron bubbled danceable grooves, sexually-suggestive lyrics (with a light garnish of the old Tyrannosaurus Rex magic), surging flurries of intense electric guitar, irresistible melodies, tight tension leading to euphoric release and, atop it all, Bolan’s camp but indomitable vocals.

It effortlessly grooved its way to number one.

“Marc is criminally underrated as a guitarist,” Visconti told Guitar World. “All rock ’n’ rollers love T. Rex, and there’s a little bit of T. Rex in every rock ’n’ roll band”

But it was an appearance on Top of the Pops to promote Hot Love where Bolan inadvertadly invented a new genre.

With the most modest of touches of glitter applied under his eyes (actually a last minute suggestion of stylist Chelita Secunda) Bolan's underlying magical magnetism was accentuated. It was the coolest - and, for the time, bravest - thing that many youngsters had seen on television.

Glitter, sparkles and colour were in, and T. Rex stood at the vanguard of the nascent ‘glam rock’ scene.

In their music and in Bolan's flamboyant persona, T. Rex also seemed to represent a riposte to traditional gender norms - something which David Bowie was all too keen to develop even further.

But for now, this was Marc's time to shine.

Though there was some consternation from some viewers at the feminine-coded performance, Bolan made no apologies for his make-up clad, sexually ambiguous pose and vocal delivery.

“I'm sorry if my actions upset some people but I'm absolutely honest about what I'm doing and I know it gives a lot of people pleasure. Those who are offended can always switch off,” Bolan told Record Mirror at the time.

Proving to all cynics that T. Rex were far more than just a chart-angled singles act though, was the towering Electric Warrior. It was the band’s second album as T. Rex and sixth overall when counting their folkier earlier incarnation.

Driven by the immense surprise that strangely enough, his once tiny fanbase had now swelled to encompass the entire country, Bolan's sights were fixed across the pond.

Now constantly busy with press appointments and gigs, Marc struggled to find time to build out the array of (blinding) songs that would make up the album, and ultimately prove hugely influential over successive British pop luminaries.

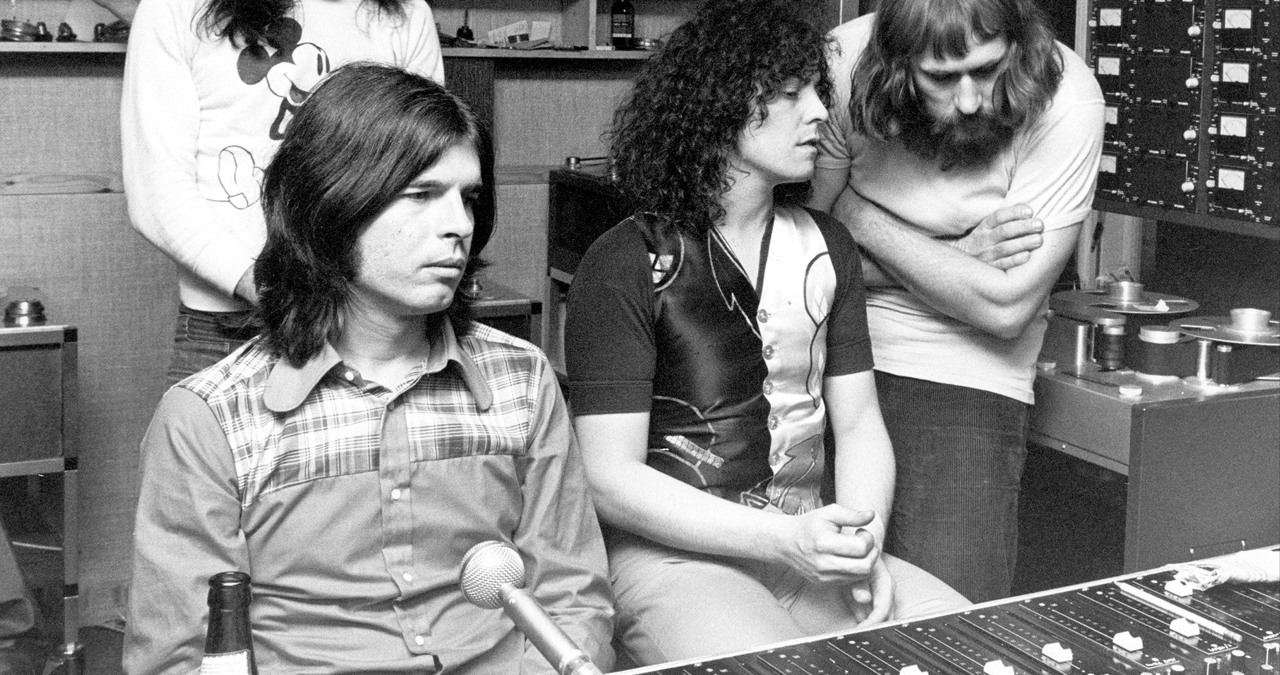

Produced by the brilliantly inventive Tony Visconti, Electric Warrior’s tracks were recorded across a range of studios as the band toured the US (although a few preliminary recordings took place at London’s Trident Studios).

Songs were largely carved-out on tour buses or in quiet evenings in hotel rooms. Largely embracing the more electric guitar-driven direction came such formidable cuts as Lean Woman Blues, Mambo Sun and future single Jeepster, while elsewhere, Bolan's more esoteric spirit flourished via the philosophical Life’s a Gas, the bucolic Girl and the utterly exceptional Cosmic Dancer.

"It's probably the loosest album I've ever recorded because it was done between gigs in America,” Bolan told Record Mirror. “I was essentially concerned with putting down rough tracks to establish a sound but they felt so good that we kept them after for the finished track. It's a highly communicable album and that is the name of the game as far as I'm concerned.”

The song which would become T. Rex’s most ubiquitous was also birthed during this frantic period.

“By the time we made Electric Warrior we were hungry for the hits, to be regarded to be in the same league as the big boys,” Visconti recollected to The Quietus.

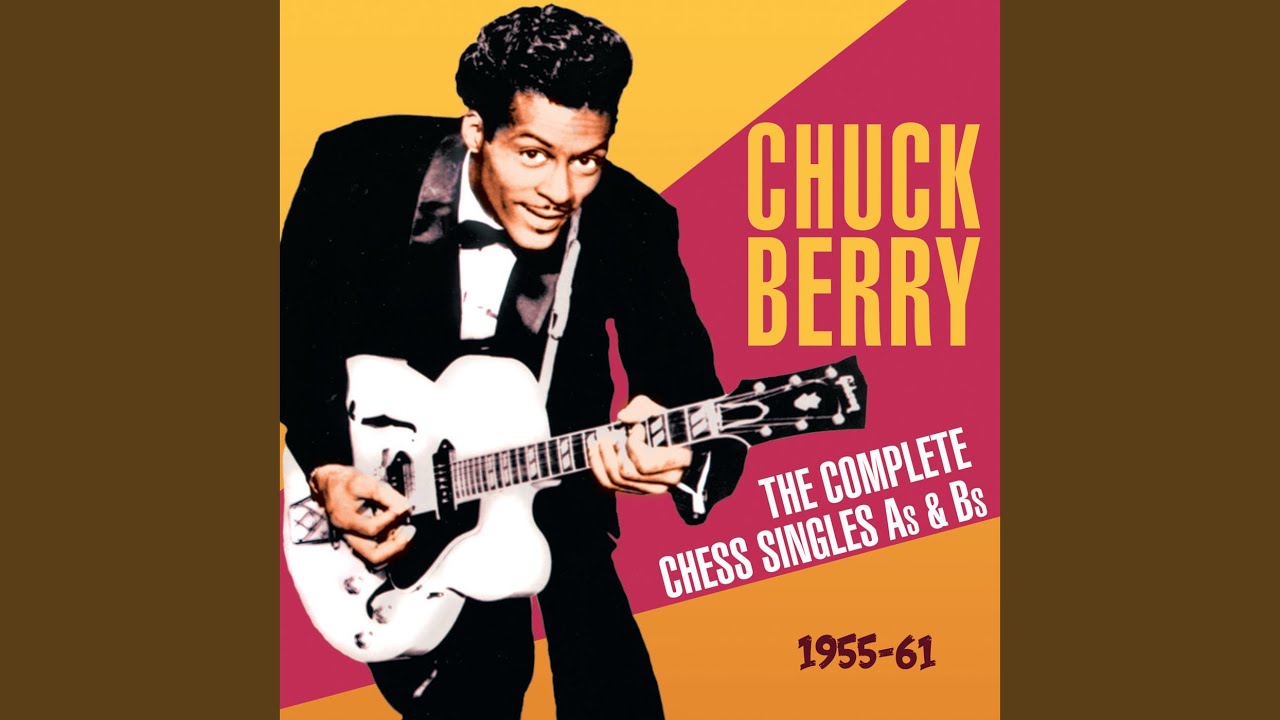

First rustled up during a break on that March 1971 US tour, Get It On’s iconic riff grew out of an attempt to learn and record Chuck Berry’s faster-paced foundational rock 'n' roll trailblazer, Little Queenie. Slightly altering the E-major riff, and tempo, Bolan morphed it into an entirely fresh song.

“I wasn’t really trying to do anything. All that happened was that I had become bored with the way rock was being presented, while musically I was… just into Chuck Berry,” Bolan told NME. “That’s why T. Rex sounds like it does. I mean, when I wrote Get It On I was just trying to re-write Chuck’s Little Queenie."

Bolan’s new lyric, as clear from its title, was an obvious allusion to sex.

“My music is all about sex. Get It On is a great screwing record,” Bolan told journalist Spencer Leigh in 1976. “I bet over 20,000 kids have been conceived to that one.”

More than just a producer, Bolan’s close friend Tony Visconti has later revealed that he personally believed that each of Get It On's three verses’ descriptions of its ‘you’re my girl’ subject were referring directly to a trio of women with whom Bolan had very real relationships with.

Well, you're dirty and sweet

Clad in black, don't look back, and I love you

You're dirty and sweet, oh yeah

Well, you're slim and you're weak

You've got the teeth of the Hydra upon you

You're dirty sweet, and you're my girl

As drummer Bill Legend recalled in an interview with Wall Street Journal, “In New York, I bought a black Gretsch wooden snare drum for touring. It had a bigger, solid sound. At our hotel, Marc had me come to his room with the drum. He sat against the bed’s headboard playing his guitar and singing Get It On. I accompanied him, and we worked out a few drum ideas."

While sat in his room, Bolan played the embryonic Get It On to its eventual producer. Wide-eyed with excitement, Visconti sensed that Bolan had landed on a potential contender for their first transatlantic hit. He giddily scribbled down production ideas and realised that time was of the essence.

Seizing on the momentum, Visconti booked some time (via former Turtles members Howard Kaylan and Mark Volman) at Wally Heider’s studios in Hollywood to bottle the future rock behemoth.

“First, I recorded a basic rhythm track with Bill’s drums, Steve’s bass and Marc’s rhythm guitar,” Visconti recollected in a fascinating interview with the Wall Street Journal. “This session included Marc’s opening riff played on his white Stratocaster.”

As Visconti recounted, his role in the studio during the making of Electric Warrior was much more integral than just that of the song's producer. He undertook a hands-on, creative director role, suggesting new routes and intrepid instrumental ideas.

For Get It On, Tony envisioned a kaleidoscope of instruments (piano, strings, sax and lush backing vocals) building out the arrangement to the point where it sounded like the most raucous, memorable party you've ever been to.

“As soon as the basic rhythm track was done, Marc picked up his second guitar - a late-‘60s Les Paul with an orange top,” continued Visconti in the Wall Street Journal interview. “Marc played lead with it and used some cool guitar effects - a wah-wah pedal, a treble booster and a Fuzz Face pedal for distortion.”

When tracking his vocal, Bolan spontaneously threw in a knowing nod back to its starting point, singing the Little Queenie-referencing line ‘Meanwhile, I'm still thinking’ during Get It On's outro.

With the basic track cut, once back in the UK the finishing touches were applied at Trident Studios, including the addition of then-session piano player Rick Wakeman injecting the song's sparkling piano glissandos (by all accounts, this addition was a favour to the struggling Wakeman, allowing him to be credited and paid for session work that month!)

King Crimson’s Ian McDonald overdubbed the bombastic sax parts - in fact a double-tracked baritone sax before switching to an alto for the conclusion of the song. “I don’t know Marc Bolan’s reasons to invite me, but I must have heard the track and said, ‘Could I come and play a sax solo on it?’ or something like that,” McDonald told Let It Rock.

Considering its impact as a single, Visconti realised the mix would need to be light and propulsive to grab those casually listening on lo-fi AM radio.

“I mixed it bright and thumpy. I also tightened up the sound of Marc’s guitars by compressing them on the mix,” Visconti relayed to the Wall Street Journal.

Upon release, that hard work paid off, and the jubilant Get It On roared to the top of the UK charts.

So far so good, but Get It On's real target was success on the US Billboard chart…

Having being renamed Bang a Gong (Get It On) in the US to avoid confusion with Chase’s own song titled Get It On - released earlier that year - heavy airplay and its classic rock-recalling riff motored Get It On upwards.

It finally achieved what had been long-though a distant dream of Bolan's, US chart victory. It reached the top ten (at a not to be sniffed-at number 10) of the US chart, proving Visconti and Bolan's hunch right.

Although it would be T. Rex’s only major US hit, in the UK, the international success of Get It On all-but coronated T-Rex as pop's ascendent sovereigns.

Suddenly, everyone wanted to be seen with them, from Elton John to Ringo Starr.

Waiting in the wings to grapple with Bolan for that baton, was one David Bowie.

“[Marc] struck it big and we were all green with envy,” Bowie reportedly told journalist Paul Du Noyer. “It was terrible: we fell out for about six months. It was ‘He’s doing much better than I am.’”

While some of T. Rex’s long-haul fans guffawed at this once niche concern becoming a household name, Bolan remained a strident figure, and declared Get It On as one of his high watermarks.

"I honestly believe Get It On was one of the best things I've ever done and the only kind of criticism I'm going to accept about it is that if someone can say, 'Well, that's out of tune or the guitar work is crap.' OK but I know it isn't."

Sadly, just six years later, Bolan would meet an untimely end following a tragic car accident in September 1977. However, his enduring legacy as one of British pop’s most compelling figures had long been settled by dent of the embarrassment of riches that T. Rex would continue to produce in the early 1970s.

The likes of Metal Guru, Children of the Revolution and 20th Century Boy have gone on to be key texts for anyone with a passing interest in learning the guitar and, perhaps, starting a band…

What Bolan represented, to the legions of youngsters watching at home was the technicolor promise of music as something to both invest yourself and believe in.

Bolan and his successors revealed a route out from the boredom and monotony of suburban life, Living proof that ascension via music was an achievable dream for all.

All they had to do was pick up their instrument, and, through sheer force of will, make it happen.

It's a contract that was echoed in that 1994 Oasis’ song, its riff re-conjuring that quintessentially Bolan-brewed sorcery that had seized the youth of Britain in 1971.

“I always say that T. Rex were my band when I was a kid,” Johnny Marr reflected to The Quietus in 2015. “What I mean by that is so much of my identity was about being a T. Rex fan. A bit like choosing your colours as to which football team you would support, when I was nine or ten I found T. Rex.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.