"When he felt the spirit, he was untouchable" – the story of Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton and Peter Green

Two legendary players. Two near-mythical Les Pauls. Two all-time-great blues albums and the greatest guitar handover in blues history

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

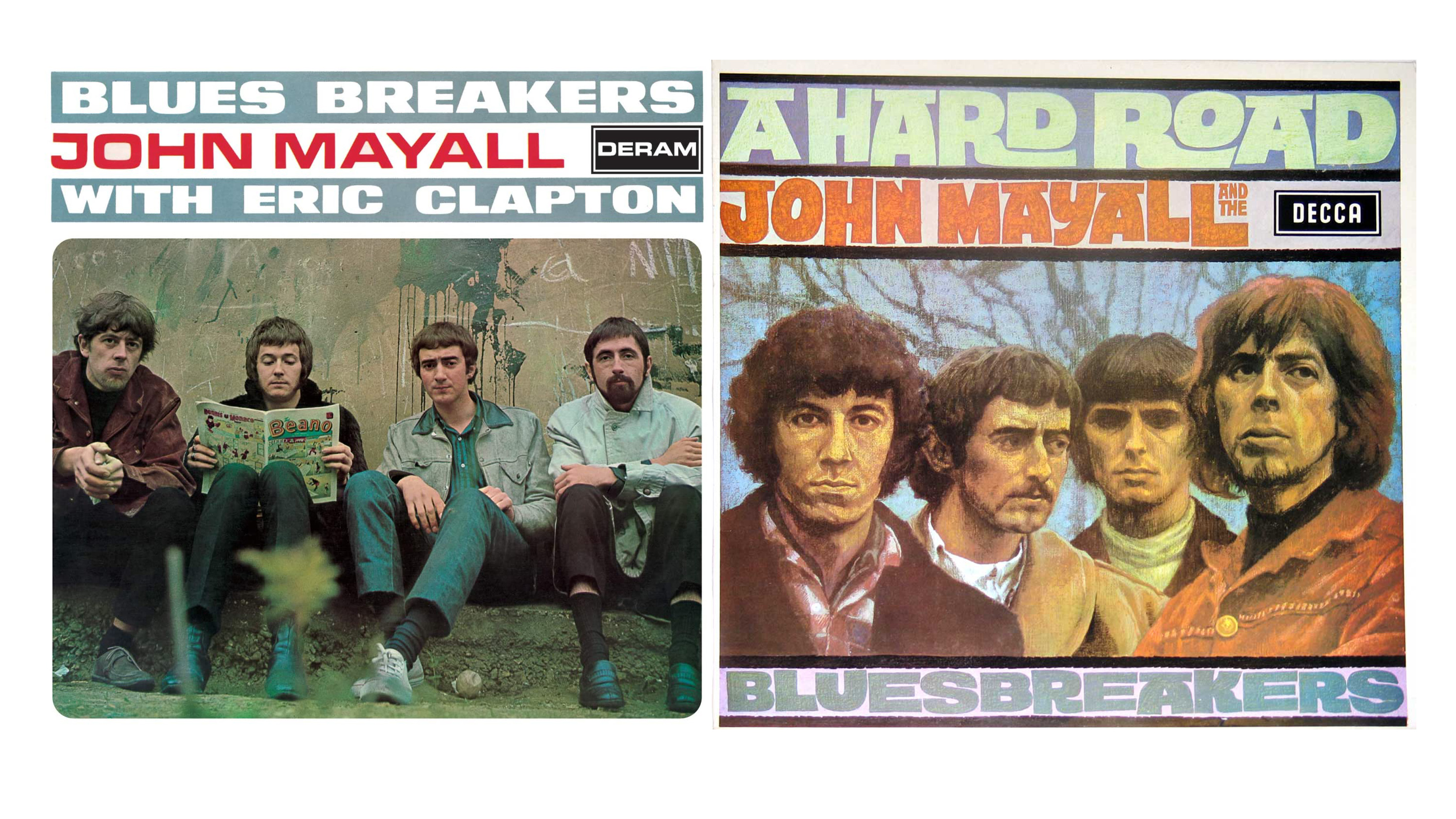

Between 1965 and 1967, Eric Clapton and Peter Green blew through John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and lit the fuse of the British boom. This is the true story of the greatest handover in blues history…

It is May 1966, and the Decca Studios are quaking. Work stops. Employees wince. In the canteen, the seismic shudder rattles teacups and prompts angry objections. Little do the complainants realise that this racket is history being made.

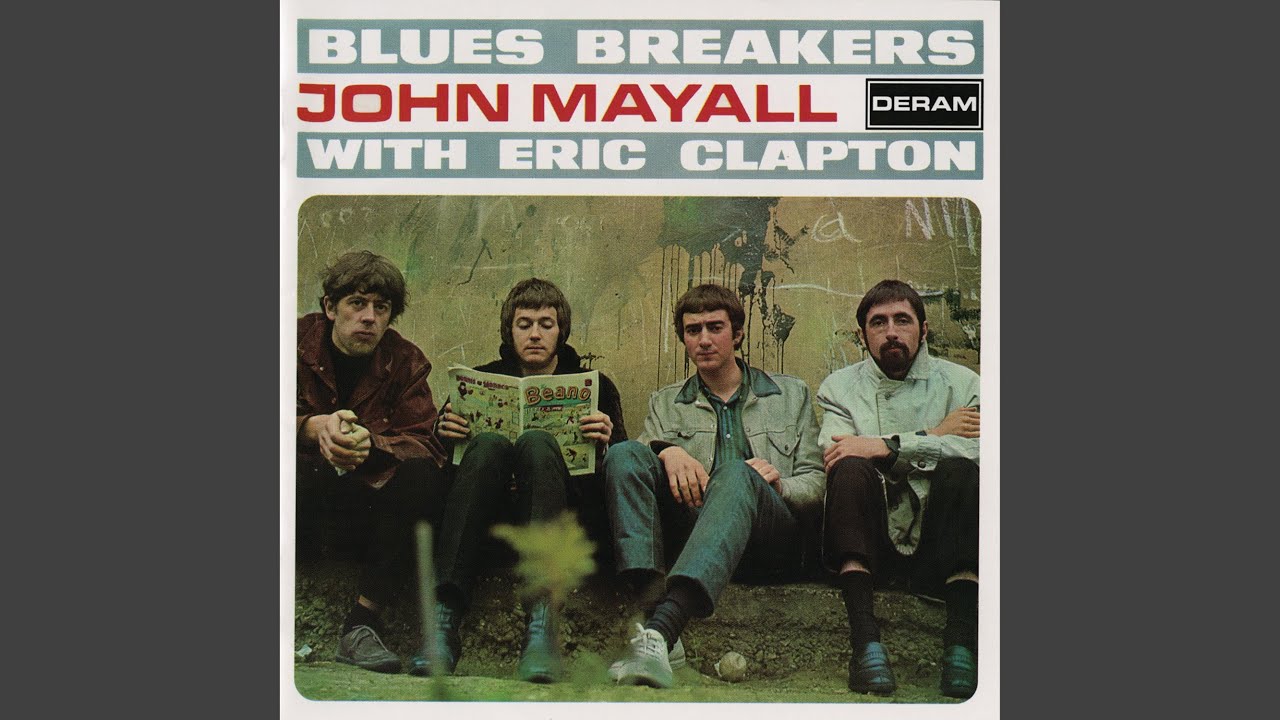

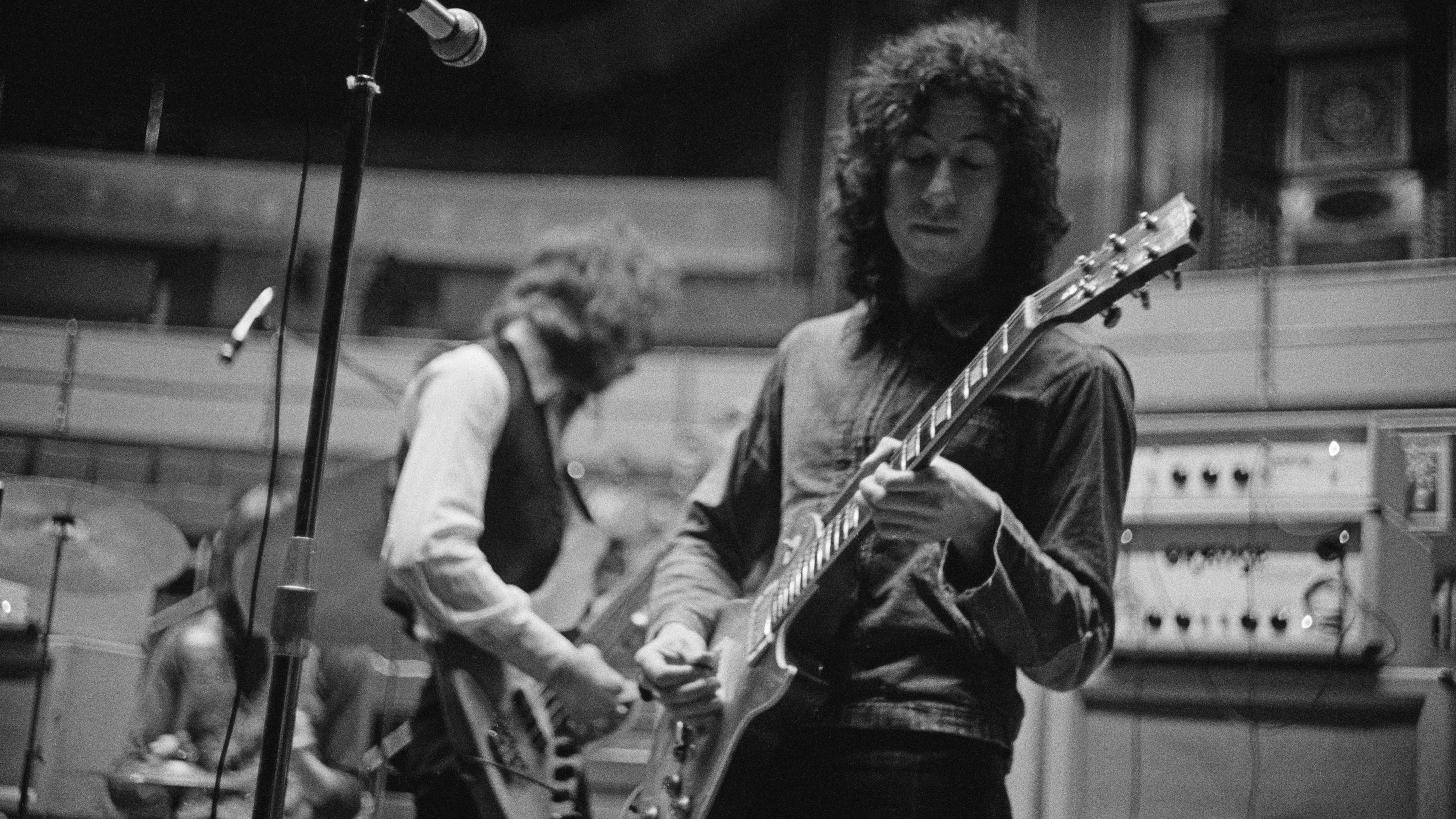

Had anyone been brave enough to enter the studio and fight through the wall of sound, they would have found a 21-year-old Eric Clapton at the eye of the storm, toting a Les Paul, driving a Marshall into the red, tracking the songs that would light the fuse of the blues boom on an album officially titled Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, but would become known to all as ‘Beano’. “Nobody had witnessed someone coming into the studio, setting up their guitar and amp, and playing at that volume,” the album’s producer, Mike Vernon, recalls.

Article continues belowPerhaps Clapton’s primal scream was understandable. By the time he came to record Beano, the precocious guitarist already had plenty to get out of his system. A troubled young man with a tangled family background, his eye-popping ability had seen him deified in the Yardbirds, but by March 1965, he was despairing of the pop direction taken by the R&B combo and hungry to play the blues. “We had completely sold out,” he wrote in his memoirs. “By then, I was a pretty grizzled and discontent individual.”

New directions

While Clapton retreated into the Oxfordshire countryside to lick his wounds, another pivotal figure was eyeing his progress. Older and wiser, with a gruff authority and a scholarly appreciation of American blues, John Mayall had moved from Manchester to London in 1963 at the suggestion of scene figurehead Alexis Korner. Mayall’s band – the Bluesbreakers – were well-respected, but his 1965 debut album was too purist to compete with the prevailing R&B-lite, sold poorly, and saw him dropped from the Decca label.

I was very grateful that someone saw my worth, and my thinking was that maybe would be able to steer the band towards Chicago blues, instead of the sort of jazz blues they were currently playing

Eric Clapton

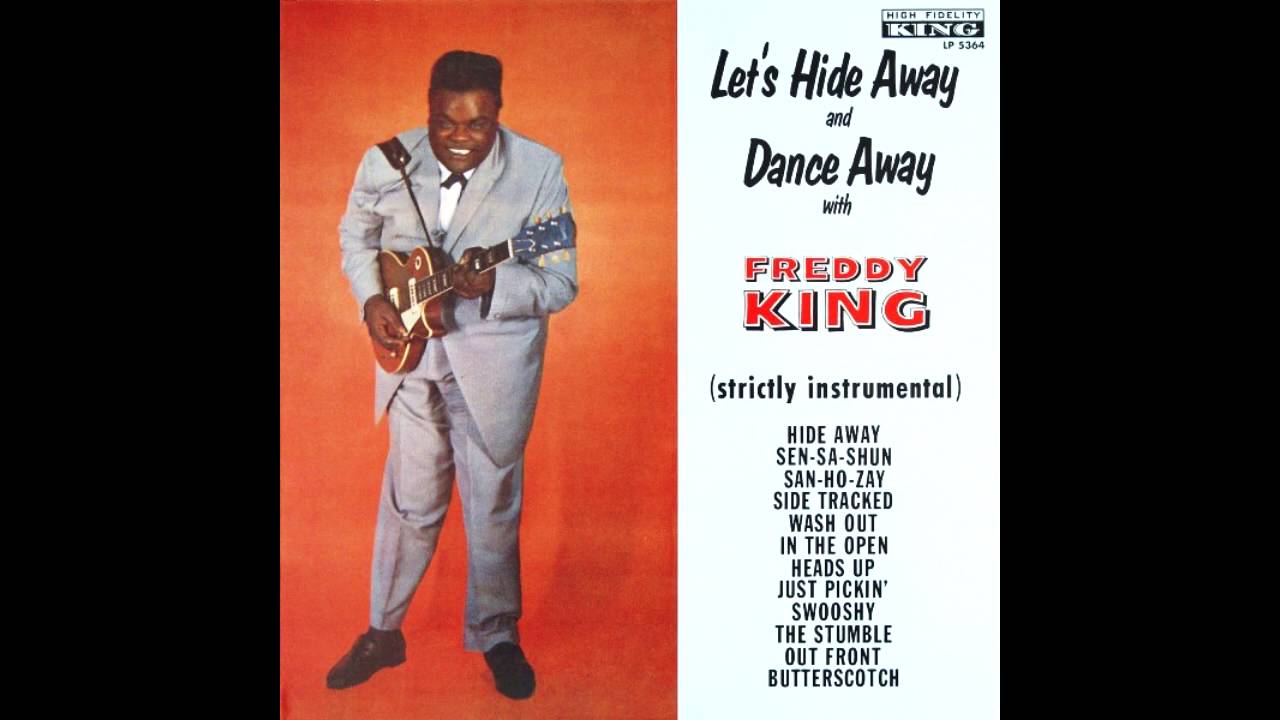

Mayall recognised that the Bluesbreakers lacked a guitarist to channel the hard, lean, electrified attack of Chicago players such as Freddie King. And so, on 28 March 1965, he gathered his rhythm section around a jukebox in Nottingham, played the Yardbirds’ necktingling B-side Got To Hurry, and suggested they hire the ousted guitarist. “Eric was the first guitarist I heard,” remembers the bandleader, “who had it.”

“I was very grateful that someone saw my worth,” picks up Clapton, “and my thinking was that maybe would be able to steer the band towards Chicago blues, instead of the sort of jazz blues they were currently playing.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Joining the lineup in April 1965, Clapton’s days were spent absorbing Mayall’s extensive vinyl collection in the bandleader’s attic. “Modern Chicago blues became my new Mecca,” he remembers. “It was a tough electric sound, spearheaded by people like Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker.”

By night, for a flat weekly fee of £35, Clapton stepped out with the Bluesbreakers to play shows that left a crater in the London club scene. Aware that his new recruit was the group’s selling point, the wily Mayall had chosen material to suit, with cuts such as Freddie King’s instrumental Hideaway offering a showcase for Clapton’s molten phrasing and perfectly weighted touch. “When Eric felt like playing,” reflects Mayall, “You really took notice.”

Trailblazer

When the lineup descended on Decca Studios the following May, the Beano sessions were the perfect fusion of material and performance. Scan the track listing and you found a run of covers that confirmed Mayall’s fathoms-deep blues knowledge, spiced with a fistful of the bandleader’s originals.

There was Hideaway, of course – Clapton tearing through its three-minute duration with peerless soul and swagger – then there was the smack-in-the-mouth lick of Mayall’s own Little Girl, and the swooped bends and thrilling double-time break of Otis Rush’s All Your Love.

When he felt the spirit, he was untouchable

John Mayall

Memphis Slim’s Steppin’ Out was closer to a swagger, while Mayall’s slow-blues, Have You Heard, achieved lift-off when Clapton’s combustible solo entered the fray. No less powerful was the Mayall-Clapton co-write, Double Crossing Time. “One of the greatest blues guitar solos ever,” says Joe Bonamassa, who described Beano as the “template and universal language” for his 2012 album Driving Towards The Daylight. “The fire he puts into that solo is unbelievable.”

“No doubt about it, Beano was a trailblazer,” says Mayall. “It’s Eric’s first stab at notoriety. When he felt the spirit, he was untouchable. It was a novelty back then for British musicians to be playing guitar like that.”

Les Paul resurgence

What I would do was use the bridge pickup with all of the bass turned up, so the sound was very thick and on the edge of distortion

Eric Clapton

Another line in the sand was Clapton’s choice of guitar. In his early years, instruments had come and gone, from the Kay Red Devil of childhood to the ‘63 Telecaster of the Yardbirds era. But his interest in the Les Paul had been piqued by the sleeve of Freddie King’s Let’s Dance Away And Hide Away, and he didn’t hesitate upon spotting a ’59 to ’60 Cherry Sunburst example in the Lew Davis music shop. The price tag was just £120: testament to the discontinued Les Paul’s rock-bottom popularity compared to semi-hollow models.

The Chicago bluesman could also take indirect credit for Clapton’s feted Beano tone. “It had really come about by accident,” the British guitarist wrote of that honeyed roar. “I was trying to emulate the sharp, thin sound that Freddie King got out of his Gibson Les Paul, and I ended up with something quite different, a sound, which was a lot fatter than Freddie’s. What I would do was use the bridge pickup with all of the bass turned up, so the sound was very thick and on the edge of distortion.”

Another critical factor was Clapton’s amp. In this department, too, the guitarist had floundered, dabbling with a Vox in the Yardbirds, but finding the combo “too toppy”.

How Marshall’s debut amp opened a new chapter in rock ’n’ roll history

The answer came from the music shop run by one Jim Marshall, and a deceptively small 1962 45-watt 2x12 combo. “I thought the solution was to get an amp and play it as loud as it would go until it was about to burst,” says Clapton. “When I was doing that album, it was obvious that if you mic’d the amp too close it’d sound awful, so you had to put it a long way away and get the room sound of that amp breaking up.”

With the guitarist refusing to put the Marshall in an isolation room, it fell to producer Mike Vernon to help tame that shattering volume, his schemes including turning the combo to face the wall and draping a piano cover over the top. The guitarist, meanwhile, devised his own method to manage that power.

“I’d hit a note, hold it and give it some vibrato with my fingers, until it sustained and then the distortion would turn into feedback. It was all of these things, plus the distortion, that created what I suppose you’d call ‘my sound’.”

Enter Greeny

By the summer of 1966, that sound was everywhere, as Beano led the charge for Britain’s nascent blues movement, and sparked the apocryphal ‘Clapton Is God’ graffiti across London.

“The fact is,” he said, “that through my playing, people were being exposed to another kind of music, which was new to them, and I was getting all the credit, as if I had invented the blues.”

Peter Green was the next in line, that was a no-brainer

John Mayall

Perhaps not, but Clapton dragged it overground. Perhaps not, but Clapton dragged it overground. Released in July, Beano climbed to No 6 in the charts and made stars of the Bluesbreakers – but by then, their trophy guitarist had made other plans. Inspired by seeing Buddy Guy front a trio at The Marquee, Clapton had been jamming in secret with Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce since March 1966, and that summer he left for Cream.

“I had the unenviable task of explaining myself to John,” he says. “He was upset that I was jumping off the train just as it was beginning to gather speed.”

Mayall himself has always downplayed the impact of Clapton’s exit. Whether or not the bandleader felt betrayed, it doubtless softened the blow that he had another extraordinary young guitarist in the wings.

“Peter Green was the next in line,” Mayall shrugged in 2012. “That was a no-brainer.”

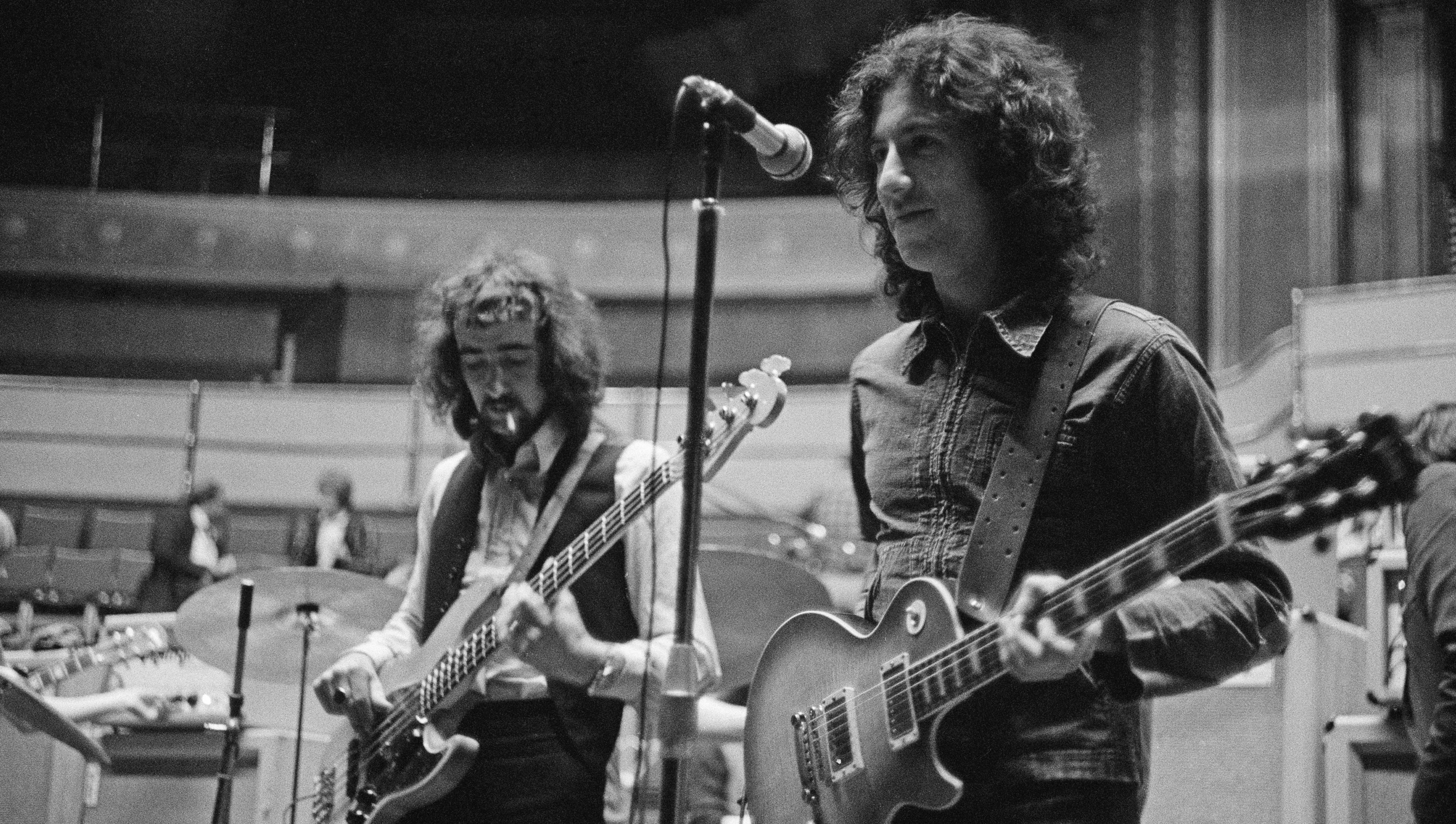

Peter Green. The name might not enjoy the same international recognition as Eric Clapton amongst fairweather music fans, but to blues aficionados, he occupies the same rarified heights. Born in Bethnal Green in 1946, and inspired by Stateside titans such as Buddy Guy, Freddie King, Otis Rush and BB King, Green had knocked about London playing bass in midtable outfits including Peter B’s Looners, until an epiphany brought him back to six strings.

“I decided to go back on lead guitar after seeing Eric Clapton,” Green remembered in 1998. remembers. “I’d seen him with the Bluesbreakers and his whole concentration was on his guitar. He had a Les Paul, his fingers were marvellous. The guy knew how to do a bit of evil, I guess.”

In August 1965, Green saw his chance to do more than spectate, as an increasingly egocentric Clapton blew off his Bluesbreakers gig to tour Greece with a motley bunch of musicians known as The Glands. “I was so unreliable, so irresponsible,” admitted Clapton. “I would sometimes just not show up at gigs and that’s how Peter Green was asked to play with John.”

Hard road to travel

While a flailing Mayall turned in desperation to a series of stand-in guitarists, Green did his best to undermine them. “Peter had pestered John to employ him,” remembers Clapton, “often turning up at gigs and shouting from the audience that he was much better than whoever was playing that night.

"Though I barely knew him, I got the impression that here was a real Turk, a strong, confident person who knew exactly what he wanted. Most importantly, he was a phenomenal player with a great tone.”

“Peter had a hard job,” says Tom Huissen, the Dutch fan whose bootlegs of the Green-era lineup were released in 2015. "He had to replace Eric, who was ‘God’ in those days. But after a couple of concerts, that whole idea was gone, because he was so amazing.

"What I remember about those concerts is that nobody was calling for Eric. They accepted Peter straight away. The way he played – it’s just phenomenal."

The fans weren’t the only ones with early reservations. As Mike Vernon admits, when the new Bluesbreakers lineup pitched up at Decca Studios in October 1966 to record A Hard Road, he struggled to believe this 19-year-old nonentity could fill Clapton’s hallowed shoes. “I noticed an amplifier I had never seen before,” recalls the producer, “so I said to John, ‘Where’s Eric Clapton?’ Mayall says: ‘He’s not with us anymore, but don’t worry, we’ve got someone better’.

I didn’t really know what I was doing on the guitar

Peter Green

I said, ‘Wait a minute, you’ve got someone better? Than Eric Clapton?’ John said, ‘He might not be better now, but you wait, in a couple of years, he’s going to be the best’. Then he introduced me to Peter Green.”

In more recent times, Green has brushed off his contribution to the album. “I’m only Eric Clapton’s replacement, I’m not Eric Clapton,” he insisted in a 1998 interview with Guitarist. “I didn’t really know what I was doing on the guitar. I was very lucky to get anything remotely any good. I used to dash around on stepping stones, that’s what I used to call it.”

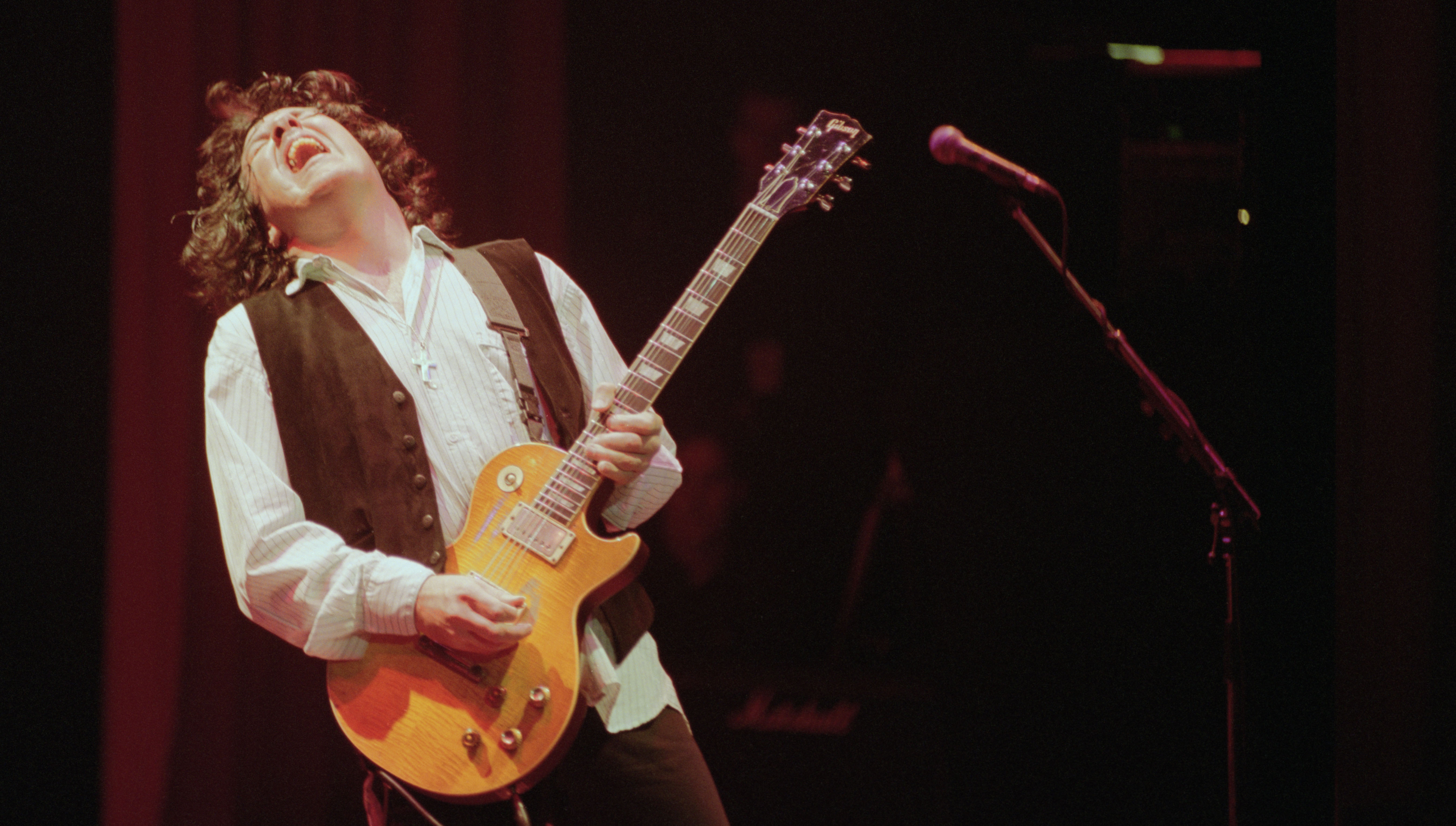

It’s hard to square that assessment with A Hard Road. The moment Green unleashed a tight, biting solo on the opening title track, any sense of Clapton’s loss evaporated, and from his soulful runs on Someday After A While (You’ll Be Sorry) to his fruity showboating on Freddie King’s The Stumble, this was a masterclass of phrasing and touch.

As the standout track, Green’s self-penned The Supernatural was spookily brilliant, the guitarist conjuring ten-second sustained notes that seemed somehow right next to you and worlds away.

Phase two

Kirk Hammett on owning Peter Green's 1959 Gibson Les Paul: "It just blew me away"

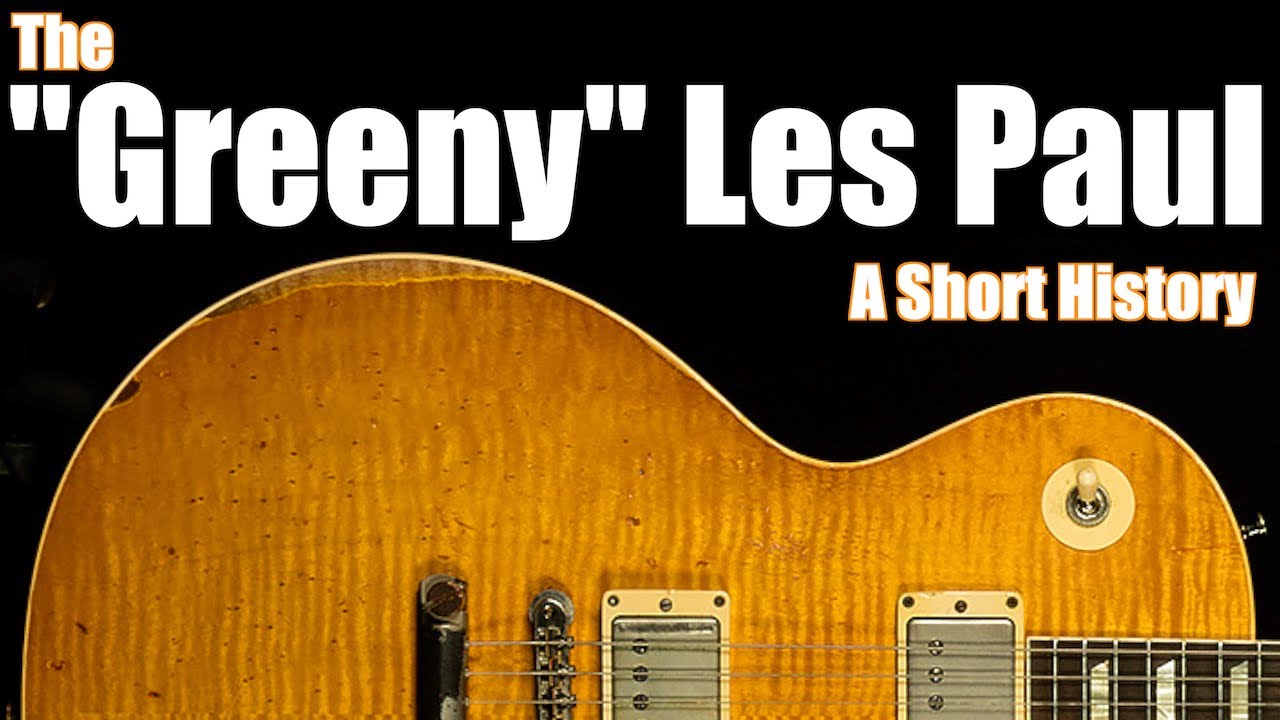

Green’s inimitable tone came from some off-kilter tools. During Clapton’s hiatus, the guitarist had auditioned using a Harmony Meteor; by the time he came aboard for A Hard Road, he was armed with a ’59 Les Paul whose quirks became legendary.

“I stumbled across one when I was looking for something more powerful than my Meteor,” Green recalled. “I went into Selmer’s in Charing Cross Road and tried [a Les Paul]. It was only £110 and it sounded lovely and the colour was really good. But the neck was like a tree.

Faced with such raw soul, it’s not hard to understand why BB King considered Green’s 'the sweetest tone I ever heard

"It was very different from Eric’s, which was slim. I’ve never seen another guitar with such an old-fashioned neck. But I couldn’t consider a Telecaster for some reason, and I didn’t want a Strat. Mine [LP] was a funny old fuddy-duddy, sweet old thing.”

The defining feature of Green’s ’59 lay in the electronics: the neck pickup had been removed, then replaced backwards. Combined with a Marshall amp, 4x12 cabinet, studio plate reverb and his position stood near the speakers, tracks such as The Supernatural had an out-of-phase quality and a sense of distance that was spellbinding.

Faced with such raw soul, it’s not hard to understand why BB King considered Green’s “the sweetest tone I ever heard”, or Walter Trout’s opinion that he was “the British blues guy who astounded me most in his heyday.”

The defining feature of Green’s ’59 lay in the electronics: the neck pickup had been removed, then replaced backwards. Combined with a Marshall amp, 4x12 cabinet, studio plate reverb and his position stood near the speakers, tracks such as The Supernatural had an out-of-phase quality and a sense of distance that was spellbinding.

Faced with such raw soul, it’s not hard to understand why BB King considered Green’s “the sweetest tone I ever heard”, or Walter Trout’s opinion that he was “the British blues guy who astounded me most in his heyday.”

Legacy

“Do I ever wish I’d had longer working with Peter? No. You can’t think in terms like that."

John Mayall

But no heyday lasts forever, and on its release in February 1967, A Hard Road proved a case of history repeating. The album gave Mayall another chart hit, reaching No 8, but once again, the bandleader found himself deserted by his star player, as Green left that same summer to form Fleetwood Mac with Breakers alumni Mick Fleetwood and John McVie.

“Do I ever wish I’d had longer working with Peter?” Mayall pondered. “No. You can’t think in terms like that.” Post-1967, the principals in this story enjoyed mixed fortunes. Clapton went from Cream to a solo career that thrives to this day. Green’s early flush of success with Fleetwood Mac was derailed by mental health issues, and though he later reemerged with the Splinter Group, many argue his touch never quite recovered.

Buoyed by the pair’s all-star patronage, the Gibson Les Paul was reintroduced in 1968, becoming the choice of bluesleaning rockers from Jimmy Page to Paul Kossoff.

Mayall, as ever, rolled on, snapping up future Rolling Stone Mick Taylor and recording Crusade. As for Beano and A Hard Road, the bold, ballsy, utterly British guitar playing on those two seminal albums kick-started the rise of a heavier, hairier brand of blues as the 70s loomed into view.

“If you want to know where it all began, in terms of both the '60s blues boom and the heavy rock we got into,” says legendary Black Sabbath guitarist, Tony Iommi, “it goes back to John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers…”