Which piano scales should you learn first?

Build the foundation of your piano or keyboard playing with these essential scales - plus video lessons

There are some mildly annoying things in life that are, sadly, unavoidable - taxes, car insurance and ‘Accept All Cookies’ buttons on websites are just three that spring to mind. If you’re learning to play the piano or keyboard though, there’s a fourth contender that you could conceivably add to that list, and that’s scales.

The mere mention of scales is usually enough to elicit groans of dismay from most piano students. Love them or hate them however, it’s an inescapable truth that learning and practising scales is an extremely helpful, if not essential part of the process, especially if you’re self-teaching. Not only do they teach you the all-important intervallic patterns needed for improvising over chords, as a form of exercise scales are incredibly useful for building finger strength, accuracy and dexterity.

There are many different types of scale out there though - 12 major scales and at least 36 minor scales just to begin with - so a common question asked by beginner pianists is, which scales should I learn first?

What is a scale anyway?

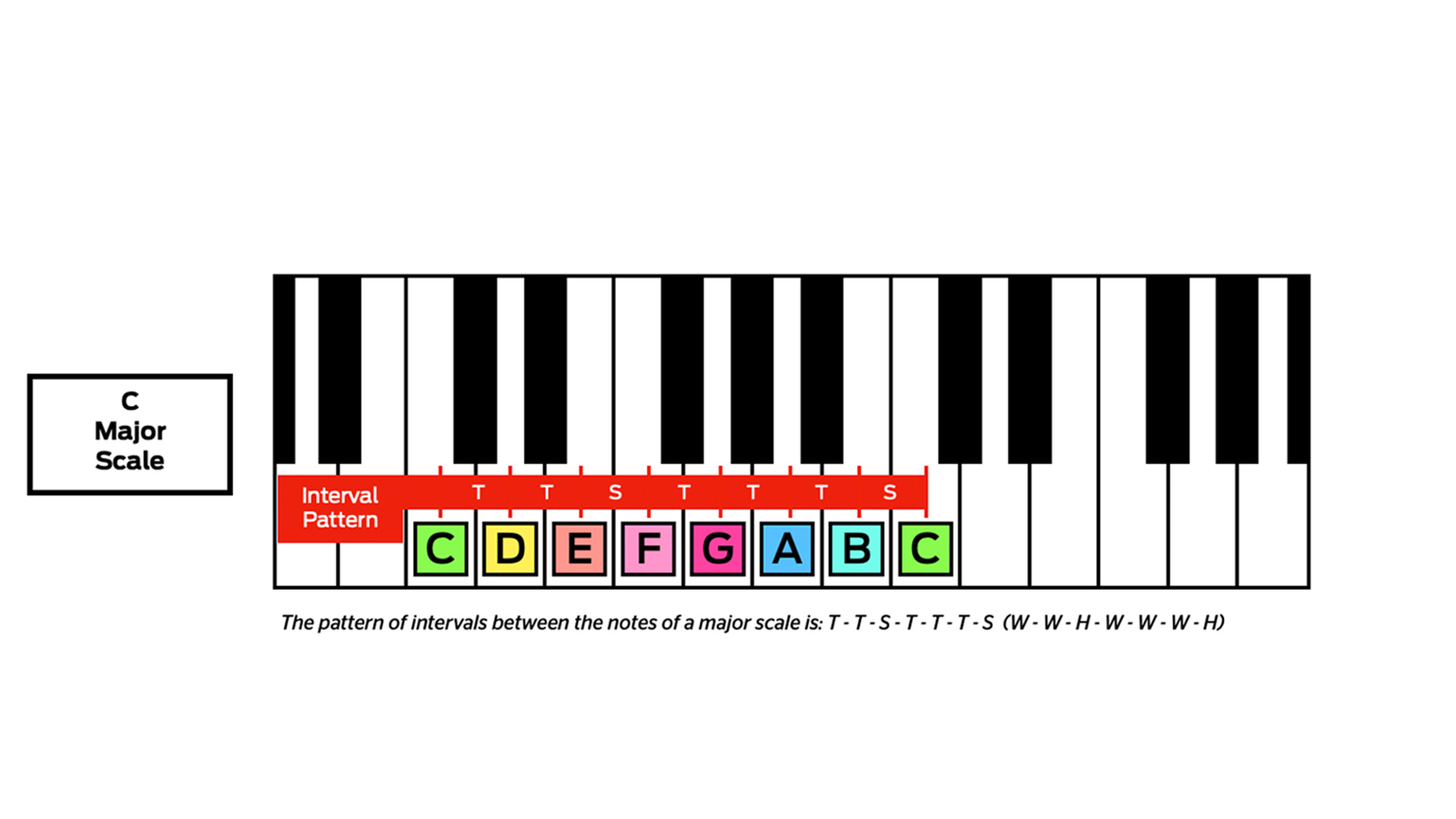

When you play any two notes on a piano keyboard, there will be a difference in pitch between them known as an interval. For example, the interval between the notes C and D is two semitones, or a whole tone. Alternatively, the interval between the notes E and F is one semitone, or a half tone. A scale is just a predetermined sequence of consecutive notes with a particular pattern of intervals between them, and the note that the scale starts from is known as the root note of the scale. So if you start from a C note and play the set pattern of intervals for a major scale, you’ll be playing a C major scale.

So, listed below are the most commonly used scales that represent the best starting points for new players to use when practising, whether you’ve just purchased yourself a new beginner keyboard or a fancy digital piano. We’ve included a short video clip of how each scale should look and sound, a diagram of the notes involved, each scale’s interval pattern and a guide to the most effective fingering for each.

Major Scale

In the notes for each scale in this article T = tone, S = semitone, W = whole step, H = half step

The major scale, in particular the C major scale, is the most common starting point for beginners to learn and practice, largely because of the fact that it’s made up of the white notes on the keyboard, making it easy to memorise. If you start on a C note anywhere on your keyboard and play all the white notes going up to the next C, you’ve just played a one-octave C major scale.

The correct fingering for a scale is important - it may sound obvious, but when playing eight notes with only four fingers and a thumb, putting the right fingers on the right keys makes things much easier to cover the whole scale from the outset. In the case of the C major scale, the first three notes are played with thumb, index and middle finger respectively, after which your thumb should pass under to play the fourth note, followed by all remaining fingers in turn. When descending, the reverse is true, with the middle finger crossing over the thumb to play the sixth note.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

- Name: Major Scale

- Interval Pattern: T-T-S-T-T-T-S / W-W-H-W-W-W-H

- Fingering (Right Hand) (C): 1-2-3-1-2-3-4-5

- Fingering (Left Hand) (C): 5-4-3-2-1-3-2-1

Since there are 12 notes in an octave, it follows that there are 12 possible major scales, each based or rooted on a different note. It’s a good idea to learn these in order of difficulty, which essentially translates to the number of sharps and/or flats (black notes) involved in each scale. The traditional order in which to learn major scales goes like this:

C Major

G Major

D Major

A Major

E Major

B Major

F Major

F# / Gb Major

C# / Db Major

A# / Bb Major

D# / Eb Major

G# / Ab Major

You’ll find that the most effective fingering will change according to which scale you’re playing - the thumb-tuck that works so well for the fourth note in the C major scale won’t be so easy in F major, for instance, where the fourth tone is Bb. In this case, it’s fine to play it with your fourth finger and tuck the thumb under to play the C that follows.

Natural Minor Scale

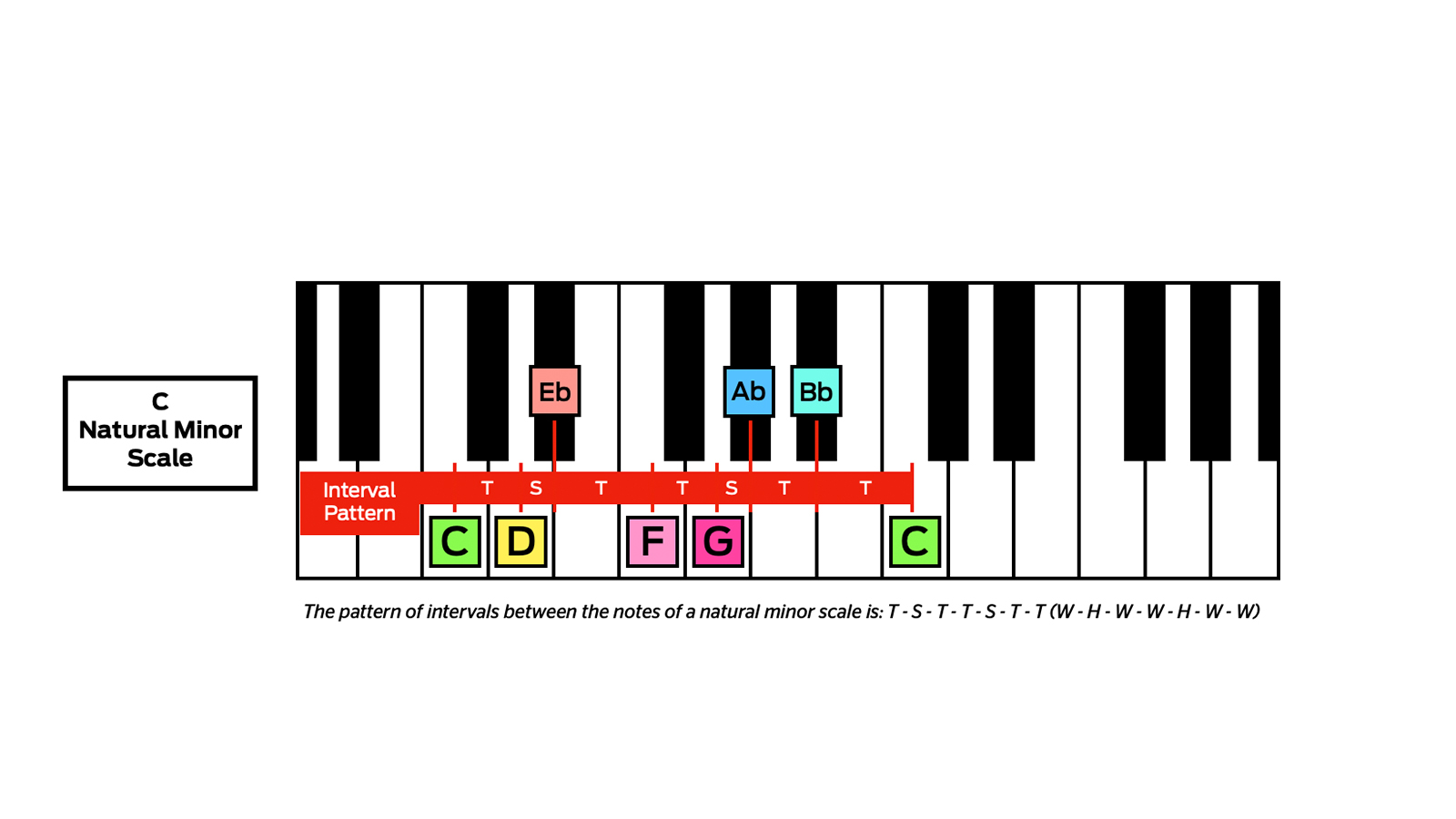

There are actually three types of minor scale - natural, harmonic and melodic, but in terms of which to learn first, we’d say that the natural minor scale is the most important, as it’s by far the most commonly used, especially if you’re just starting out.

You can play an A natural minor scale by playing all the white notes from A to A on your piano keyboard. The fingering is just the same as the C major scale, and indeed they’re all the same notes, but because we’ve started on A instead of C, it generates a different interval pattern with a different, sadder sound. Because they share the same notes, A minor is the relative minor to C major. If you play that sadder interval pattern starting on C, you get the C natural minor scale.

- Name: Natural Minor Scale

- Interval Pattern: T-S-T-T-S-T-T / W-H-W-W-H-W-W

- Fingering (Right Hand) (C): 1-2-3-1-2-3-4-5

- Fingering (Left Hand) (C): 5-4-3-2-1-3-2-1

As with the major scale, there are 12 natural minor scales to learn:

C Minor

G Minor

D Minor

A Minor

E Minor

B Minor

F Minor

F# / Gb Minor

C# / Db Minor

A# / Bb Minor

D# / Eb Minor

G# / Ab Minor

Major Pentatonic Scale

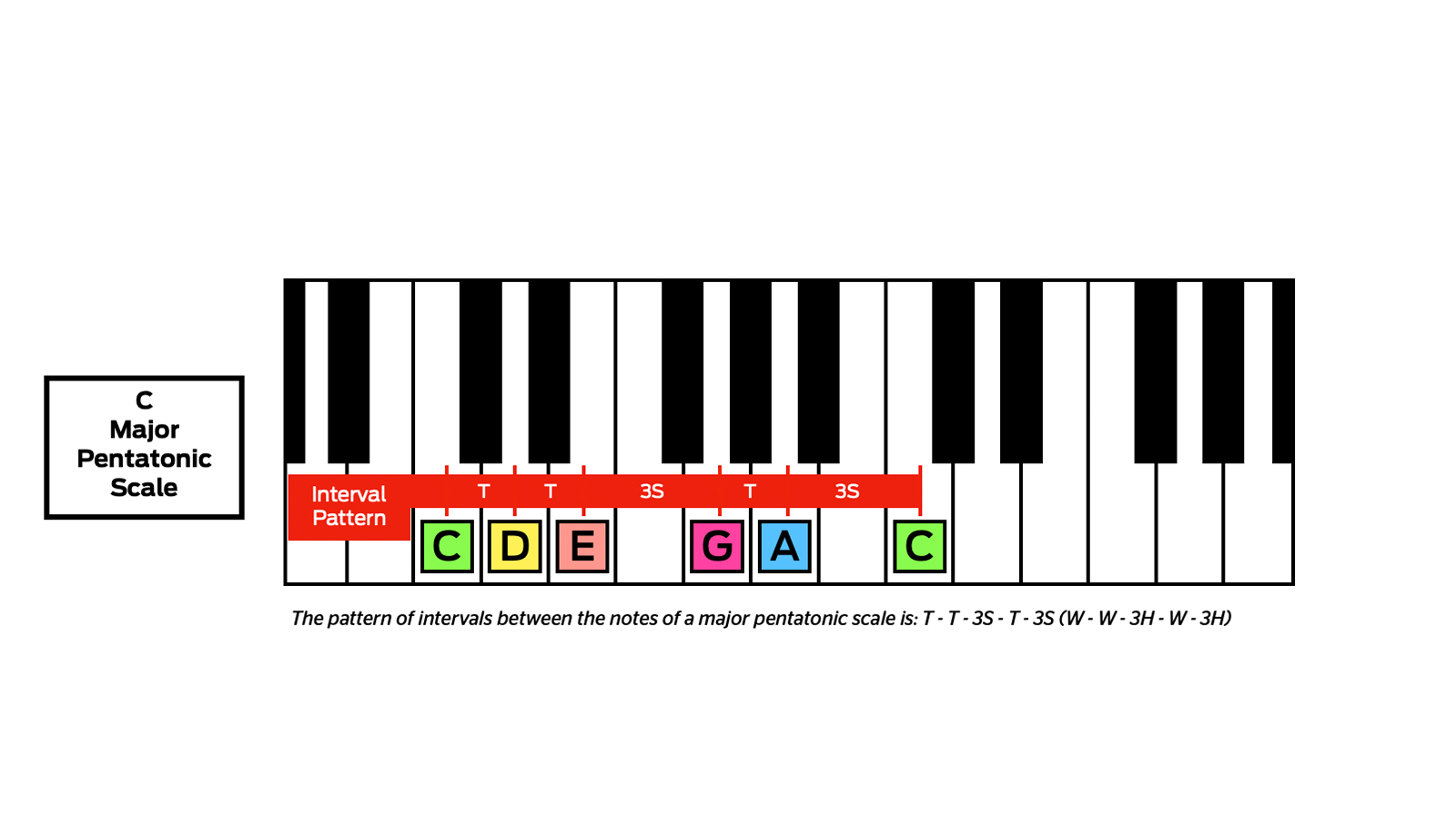

The term ‘pentatonic’ literally translates to ‘five tones’, so it’s no surprise to learn that pentatonic scales contain only five distinct notes, rather than the major scale’s seven (the eighth note is a repeat of the root but an octave higher). Pentatonic scales are extremely common in a variety of musical cultures, such as traditional Japanese, but because of their simplicity, they’re also used a lot to construct memorable melodies in pop songwriting.

The major pentatonic scale is very similar to the major scale, but with two fewer notes - the fourth and seventh tones are missing. In the case of C Major Pentatonic, that gives us the following:

- Name: Major Pentatonic Scale

- Interval Pattern: T-T-3S-T-3S / W-W-3H-W-3H

- Fingering (Right Hand) (C): 1-2-3-1-2-4

- Fingering (Left Hand) (C): 5-4-3-2-1-2

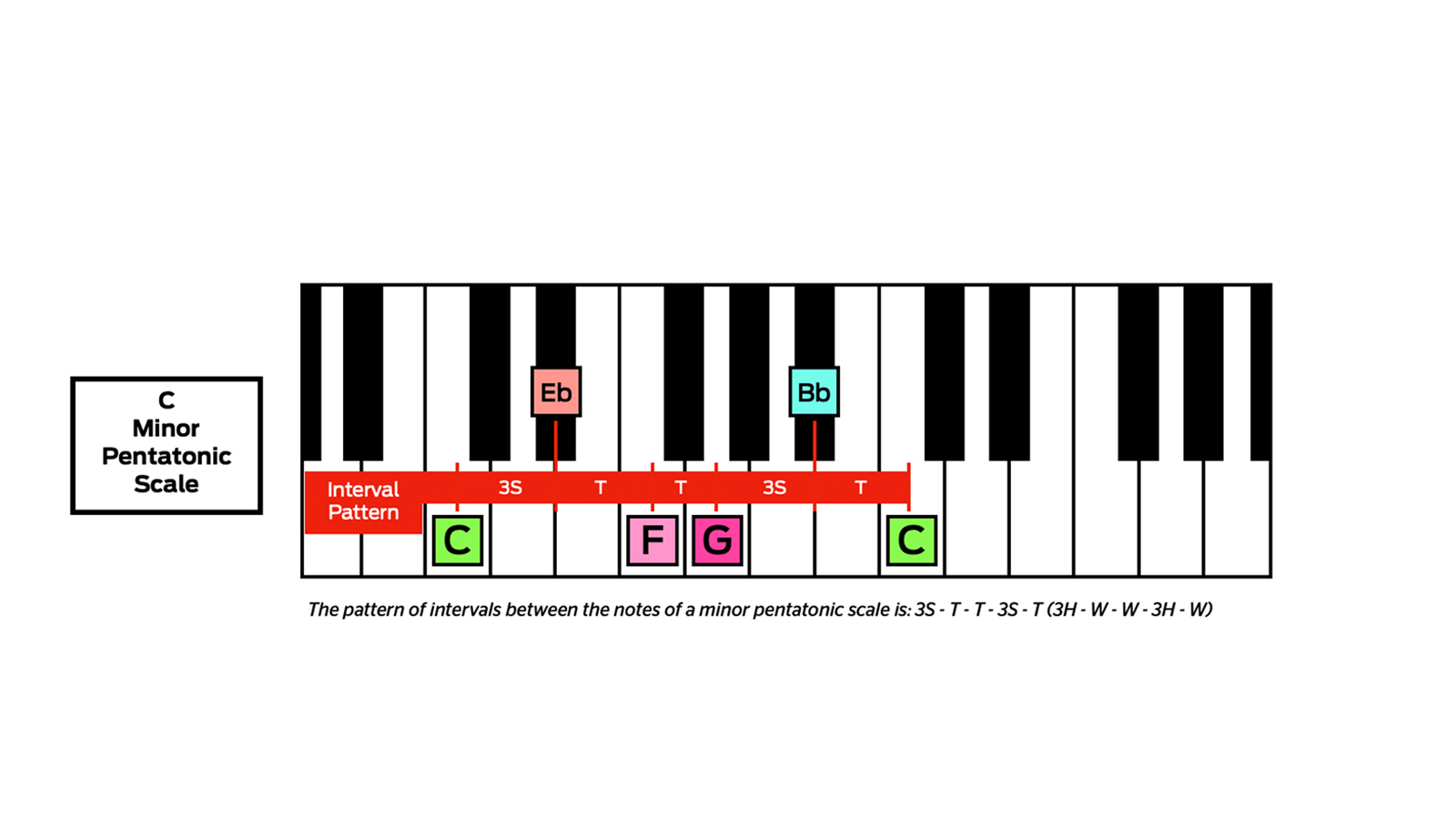

Minor Pentatonic Scale

In a similar vein, the minor pentatonic is a pared-down version of the natural minor scale, with five notes instead of seven, but the missing tones this time are the second and sixth notes. In the key of C, this delivers this result:

- Name: Minor Pentatonic Scale

- Interval Pattern: 3S-T-T-3S-T / 3H-W-W-3H-W

- Fingering (Right Hand) (C): 1-2-3-1-2-4

- Fingering (Left Hand) (C): 5-4-3-2-1-2

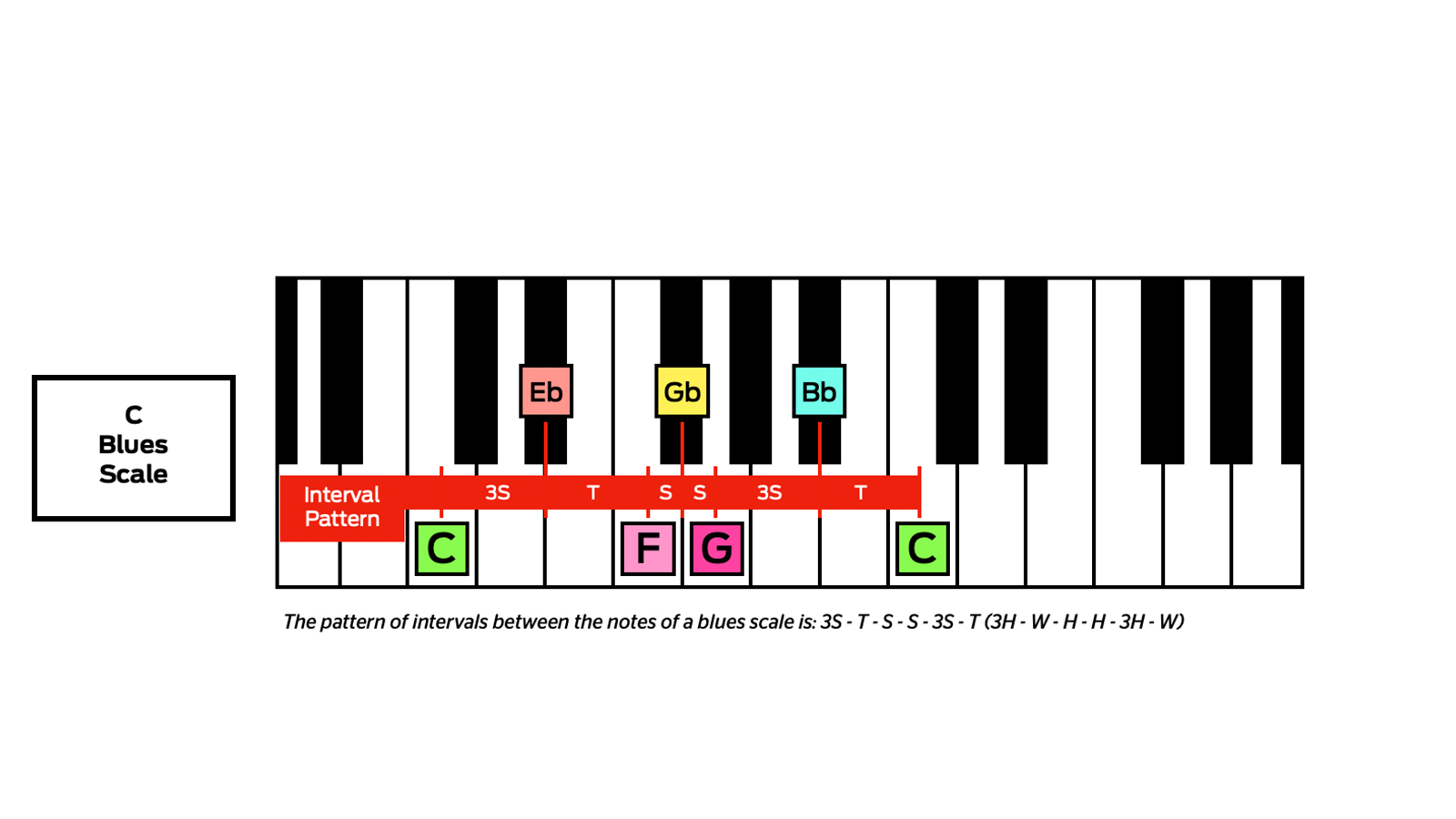

Blues Scale

The Blues scale is an adaptation of the minor pentatonic, identical except for the addition of one vital note, a sharpened fourth. With that one all-important additional ‘blue’ note, this scale is vital if you want to do any kind of jazz or blues soloing, so it’s a great one to have under your belt.

- Name: Blues Scale

- Interval Pattern: 3S-T-S-S-3S-T / 3H-W-H-H-3H-W

- Fingering (Right Hand) (C): 1-2-3-4-1-2-3

- Fingering (Left Hand) (C): 5-3-1-2-1-2

Taking things further

After a while, it may feel as if practising scales is holding you back, especially since most new players will want to rush on ahead to play the songs that inspired them to take up the piano in the first place, rather than laboriously repeating the same sequences of notes over and over. However, it’s scientifically proven that the more you stick at it, the better the end results will be.

Once you’ve mastered a scale with your right hand, practice it with your left hand, then both hands together. Use a metronome or a drum loop to keep you in time, and make sure that each note is played with equal strength. More advanced players can extend scales beyond a single octave, repeating the pattern every time the root note is reached.

If you manage to master all of these scales in all twelve keys, not only will your fingers be fit as fiddles, but you’ll be well on your way to having a solid vocabulary to build on when writing melodies and improvising over chord progressions.

Related buyer’s guides

- Sharpen up your scales with the best online piano lessons

- Boost your comfort with the best piano benches

- Enhance your set up with one of the best keyboard stands

Dave has been making music with computers since 1988 and his engineering, programming and keyboard-playing has featured on recordings by artists including George Michael, Kylie and Gary Barlow. A music technology writer since 2007, he’s Computer Music’s long-serving songwriting and music theory columnist, iCreate magazine’s resident Logic Pro expert and a regular contributor to MusicRadar and Attack Magazine. He also lectures on synthesis at Leeds Conservatoire of Music and is the author of Avid Pro Tools Basics.