“One night Zeppelin were all going down the boozer and I said, 'You guys bugger off but Bonzo, you stay behind because I've got an idea’”: The genius behind John Bonham’s towering When the Levee Breaks drum sound

It’s one of the best drum recordings in history, but the resulting sound was just as much a feat of engineering as it way playing

DRUMS WEEK 2025: Sporting one of the most beloved (and most heavily sampled) drum tracks of all time, Led Zeppelin’s spin on Memphis Minnie’s When the Levee Breaks is widely hailed as one of the rock behemoth’s finest moments.

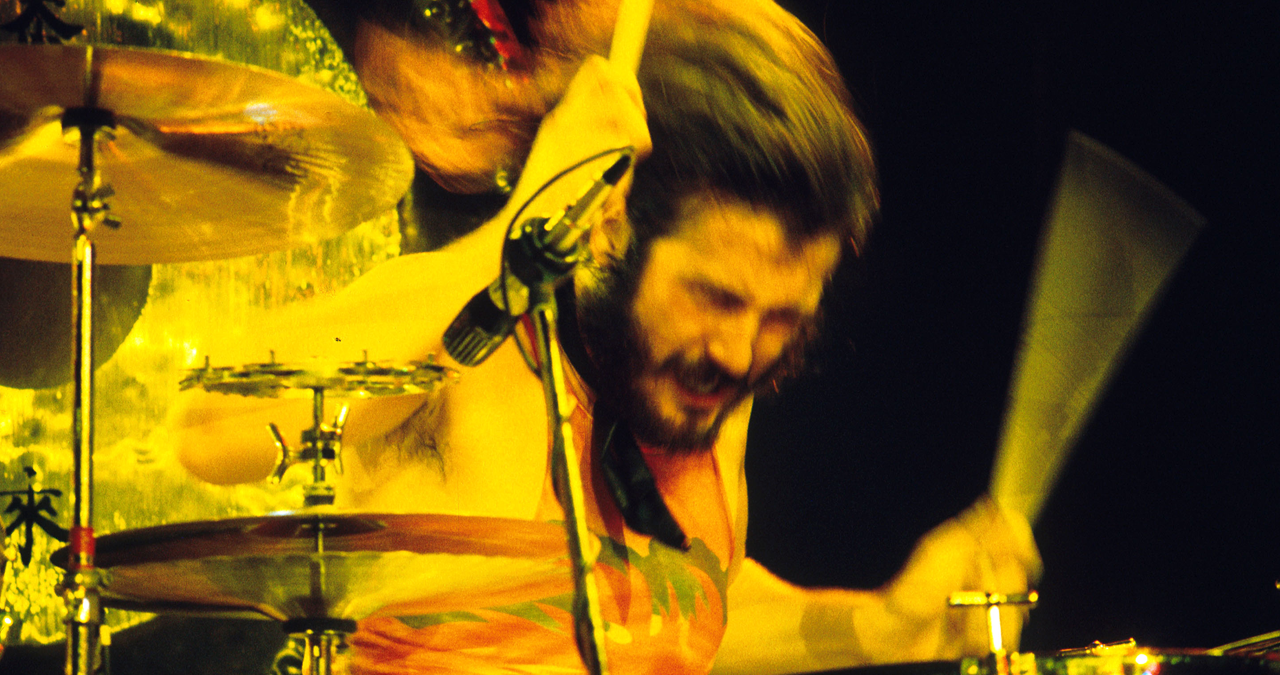

Though Robert Plant, Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones were in fine fettle across the song’s ever-shifting sands, it’s the perfectly-tailored punch and swagger of John Bonham’s drums that everyone continues to cite as its most crucial element.

Serving as the towering finale of Led Zeppelin IV, When the Levee Breaks almost entirely hinges on the momentum of Bonham’s relentless groove, captured at (and haunted with the presence of) the legendary Headley Grange.

This charming yet slightly spooky former Victorian workhouse had become a haven for the band as they attempted to return to more fundamental themes.

“It was a manse, an old Victorian house, a wonderful place, and very imposing,” Page told Classic Rock magazine in 2014. “I liked the idea of the whole band being in the same house, in residence, working. Fleetwood Mac had rehearsed there, although they didn’t record there. So I knew there wouldn’t be noise problems. It was in the countryside, so you weren’t going to have neighbours complaining. It seemed ideal.”

By 1971, a torrent of negative reviews for the band’s muddled, folkier third album had motivated Page and Plant to reconsider their direction. Though Headley Grange had been used during the recording of Led Zeppelin III, it was a location that jibed well with their next record’s ‘return to the roots’ concept, and they headed back to warm embrace of its cosy rural Hampshire environs.

With the Rolling Stones’ hyper-modern mobile recording unit (the truck-based studio which was the first of its kind in Europe) parked-up outside, the band were freed from the confines of an inner-city recording studio yet could still professionally track records as a band, whilst also soaking up the country atmosphere.

It was an important move, as Led Zeppelin IV would end up eventually being hailed as the band’s masterpiece. And, their time at the Grange would yield arguably their most popular song, Stairway to Heaven.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But we’re here today to talk about the album’s only cover, and the genesis of - in our view - the coolest sounding drum beat ever.

When the Levee Breaks was originally written back in 1929 by American Delta blues legends Kansas Joe McCoy and Memphis Minnie. A part-tribute to those that lost their lives in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the song had become a well-regarded part of the Delta blues canon.

A keen student of Memphis Minnie, Robert Plant had long earmarked it as a potential cut for Led Zep to put their own stamp on.

While Minnie's 1929 original was recorded with a humble acoustic guitar backing, it was clear that an entirely new piece of music was needed for Zepp’s 1971 interpretation.

Jimmy Page jettisoned the song’s original blues (I-IV-V) chord structure and instead concocted a more driving piece that pushed a repetitive riff relentlessly over a drone.

Written and performed by Page in open-G tuning (which was pitched down for the final studio version, which is a tone below in F), Jimmy's slick new pull-off riff was suitably propulsive, whilst also nodding to the song's bluesy origins.

Alongside a further gamut of fresh elements he’d had kicking around for a while (including that dazzling slide riff at the song’s center), Jimmy Page constructed a lengthy original framework, that had much space for the band to flex.

Pivotal to this essentially all-new song would be John Bonham’s drums. Characteristically, it didn’t take Bonham long to hit upon the perfect groove once he'd pulled up his stool.

As forceful as Page’s riff, the sturdy thrust of John's kick and snare would dissolve into a considered fill, before rhythmically punctuating the end of the verse. A deep breath, then an instant snap straight back onto that simple but powerful groove.

All the while, Bonham’s hi-hat sashaying daubed the beat with personality. It was another feat of Bonzo brilliance.

But while the beat itself was cracking, Page - who was producing the record - was keen to make sure it sounded even more heavyweight.

By dent of his lengthy studio career, he already had some ideas…

“When I was playing sessions, I noticed that the engineers would always place the bass drum mic right next to the head,” remembered Page in an interview with Guitar World in 1993. “The drummers would then play like crazy, but it would always sound like they were playing on cardboard boxes. I discovered that if you move the mic away from the drums, the sound would have room to breathe, hence a bigger drum sound.”

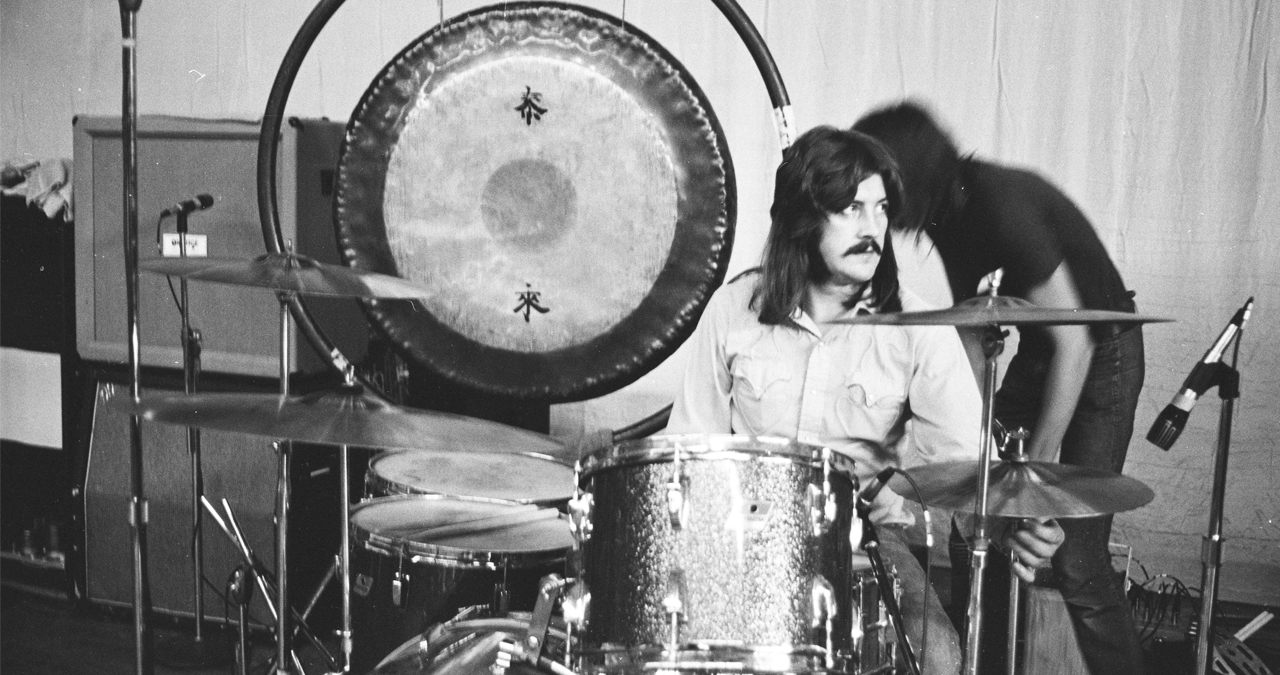

According to Page’s recollection, he was reminded of this once he heard Bonham, who’d setup his Ludwig drum kit within the Grange’s high-ceilinged lobby, knocking out a beat in the space, and summoning a jaw-dropping natural echo.

“We were playing in this drawing room to begin with, and then John Bonham had another drum kit set up in the hall, with this really high ceiling,” Page told Classic Rock. “When he started playing I said, ‘Right, we’ll have to do something in here now.’”

However, the late, great engineer Andy Johns recalled a slightly different version of events.

In fact, Johns claimed in an interview with us back in 2009, that recording Bonham’s kit in the lobby was solely his brainchild, and a technique which Page then picked up for the recording of 1975’s Kashmir.

“One night Zeppelin were all going down the boozer and I said, 'You guys bugger off but Bonzo, you stay behind because I've got an idea,’” Johns told us. “So we took his kit out of the room where the other guys had been recording and stuck it in this lobby area. I got a couple of microphones and put them up the first set of the stairs."

Regardless of whose idea it actually was, the pair had both cottoned on to the fact that, with the presence of Headley Grange’s natural reverb infused onto it, the drum part of When the Levee Breaks could potentially sound utterly incredible.

Back to the recording, and, as Johns recalled, two Beyerdynamic M 160 hypercardioid microphones were hung over the stairway which led up to the first floor above Bonham’s Ludgwig drum kit (which sported his colossal 26’ x 14’ bass drum).

The kit was positioned in the entrance hall/lobby area. Oddly, there were no microphones placed on or near the kit itself. Despite the fact that just two mics were used, the resulting recording captured a serendipitous balance of the kit’s components, with Bonham's drum hits expanding out organically into the atmosphere and enmeshing with the room reflections.

This output from the microphones was then routed to twin Helios F760 FET compressor and peak limiters which were programmed to process the incoming signal and output the result which sounded like the beat was somehow ‘breathing’.

However, another crucial element which is often underestimated is how Johns’ reigned in and manipulated additional artificial echo via Jimmy Page’s Binson Echorec.

As Johns told us back in 2009, “The [Binson Echorecs] were Italian-made and instead of tape they used a very thin steel drum. Tape would wear out and you'd have to keep replacing it. But this wafer-thin drum worked on the same principle as a wire recorder. It was magnetised and had various heads on it and there were different settings. They were very cool things!”

There was a hunch that by using the outboard compressor to expose more of the hallway’s reverberant character, and with the Binson Echorec set to 16th notes, Johns (and Page, depending on who you ask) was able to wrangle both the natural reverb and the generated echo to actually modify and expand upon Bonham’s groove with a shimmering proto-delay effect.

The Binson fused the echoey imprint of Bonham’s kick and snare in rhythmic tandem with his original groove. The manipulation of echo in this way was something that was quite unheard of at the time, but has since become commonplace in music production. It's a fundamental principle of the delay effect.

“That's how Bonzo got that 'Ga Gack' sound because of the Binson,” Johns told us. “He wasn't playing that. It was the Binson that made him sound like that. I remember playing it back in the Stones' mobile truck and thinking, 'Bonzo's gotta f*****g like this!' I had never heard anything like it and the drum sound was quite spectacular."

Upon hearing the end result of these deft engineering calculations, Bonham’s typically concise reply; “Oh yeah, that's more f*****g like it!”

With Bonham’s beat tracked, it took a little longer to get the remainder of the song’s components together. After a few unsuccessful attempts to get the full thing down at both Headley Grange and Island Studios, the band eventually finished and mixed the sprawling piece at Sunset Sound in Hollywood, California. Its vibrant musical colour fuelled by Bonham’s beat.

“When The Levee Breaks is probably the most subtle thing on there as far as production goes because each 12 bars has something new about it, though at first it might not be apparent. There's a lot of different effects on there that at the time had never been used before. Phased vocals, a backwards echoed harmonica solo. Andy Johns was doing the engineering, but as far as those ideas go, they usually come from me,” recalled Page in an interview with The Trouser Press.

Now considered one of the finest men to ever sit behind a kit, the legendary John Bonham died in 1980, and the inventive engineer Andy Johns passed away in 2013, yet the enduring influence of this feat of drum recording and production continues to resonate.

In subsequent years, of course, the magnificence of Levee's beat has become a thing of legend. With the first two bars of pure Bonham foregrounding this expertly tailored sound.

It was not unsurprising that it was clipped out and seized upon by many in the sampling era.

Perhaps most notably, it was used by the Beastie Boys on their track Rhymin' and Stealin' on their iconic debut Licensed to Ill.

As Robert Plant remarked upon hearing the Rick Rubin-produced record, in an interview with Rolling Stone, “I guess if he’s going to nick something, he might as well nick something good."

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.