Master the seemingly impossible old style of stride piano

Known to push jazz pianists to the edge

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Nothing strikes fear into the hearts of piano players like the mention of stride piano. This seemingly impossible old style is like ragtime on steroids and pushes jazz pianists to the limit.

The left-hand alternates a low bass, frequently played in tenths, with close position midrange chords, while the right hand provides melody, syncopations, lines, and runs. The total effect is a relentless, locked-down swing eighth-note feel.

Even if you can’t invest the hours necessary to master stride, studying its fundamentals will increase your harmonic language skills and centre your time feel.

Plus, there’s nothing wrong with gaining an appreciation of an almost-lost art that has inspired everyone from Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, and Oscar Peterson to Dick Hyman, Marcus Roberts, Kenny Werner, and Bill Charlap.

Beyond the flash and the bluster of stride is a deep awareness of song structure, chord voicing, root movement and harmony, and most of all, swing.

- The best MIDI keyboards for beginner and pro musicians

- Best synthesizers: keyboards, module and semi-modular synths

- Best acoustic pianos: budget to premium instruments for home and studio

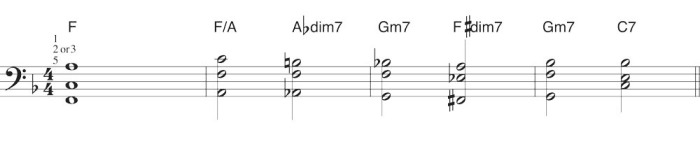

Ex. 1. When playing stride, your left hand is the rhythm section, and it never lets up. Practice getting used to the motion of your left arm, aiming low with your fifth finger to hit the bass note, then moving quickly to the middle register to grab a chord. In example 1a, the chords move from I to V7, F to C7, using an alternating bass note on beats 1 and 3. One trick: Start the V7 (C7) on the fifth (G) of the chord instead of the root. This way you don’t have to repeat a note (C). Make your bass line more melodic in 1b by starting the F6 on the third (A) in the second measure, then move down to the V7 through a passing diminished chord (Abdim7). Since you start the V7 on the fifth (G), substitute Gm7 and make a ii7-V7. Upstairs, notice the chord voicings in the last two measures. The top notes in each chord create a nice melody — D, E, D, C — and you can use your thumb to bring these out.

Ex. 2. Most of the great stride players like James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, Earl "Fatha" Hines, and Art Tatum played tenths in the left hand and sometimes added a third note with the second or third finger. The top thumb note adds a tenor voice and a rich counter-line; the effect is harmonically dense and exponentially more difficult to play. Give it a shot but don’t push it.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

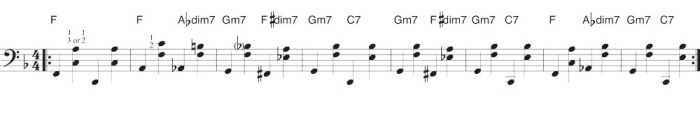

Ex. 3. Try the same constructions show in Example 2 with two hands, to make things a bit simpler. It’s not cheating to break up the tenth and, at fast tempos, this is an effective technique. Here is a complete eighth-bar A-section with a turnaround, using the passing diminished and ii7-V7.

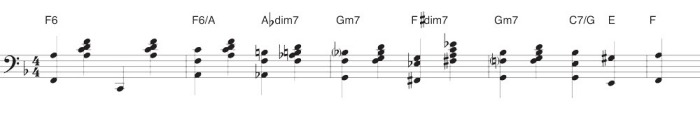

Ex. 4. If you can handle tenths, here’s how it’s done. Notice the embellishing pickup at the end of bar 4 — E to F.

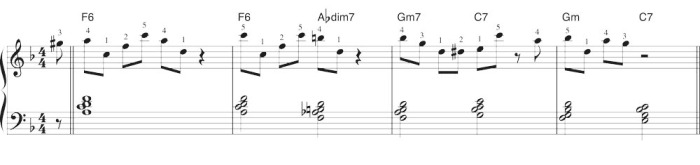

Ex. 5. The right hand in stride is based on swing eighth-note lines, usually built on broken-up chord tones. Practice this example with simple chords in the left hand and get used to really swinging the right-hand line.

Ex. 6. Using the same chords in the left hand, add some thirds. The off-beat accents really make the riffs pop, and any syncopation in the right hand will play against the pumping quarter notes of the left hand — when you add them in with the next example!

Ex. 7. Syncopate the right hand and you’re in full stride. In measure 1, the left-hand walks up in tenths; in measure 2, the right-hand syncopations push against the quarter-note pulse. You can grab an octave in the right hand whenever you want for emphasis.