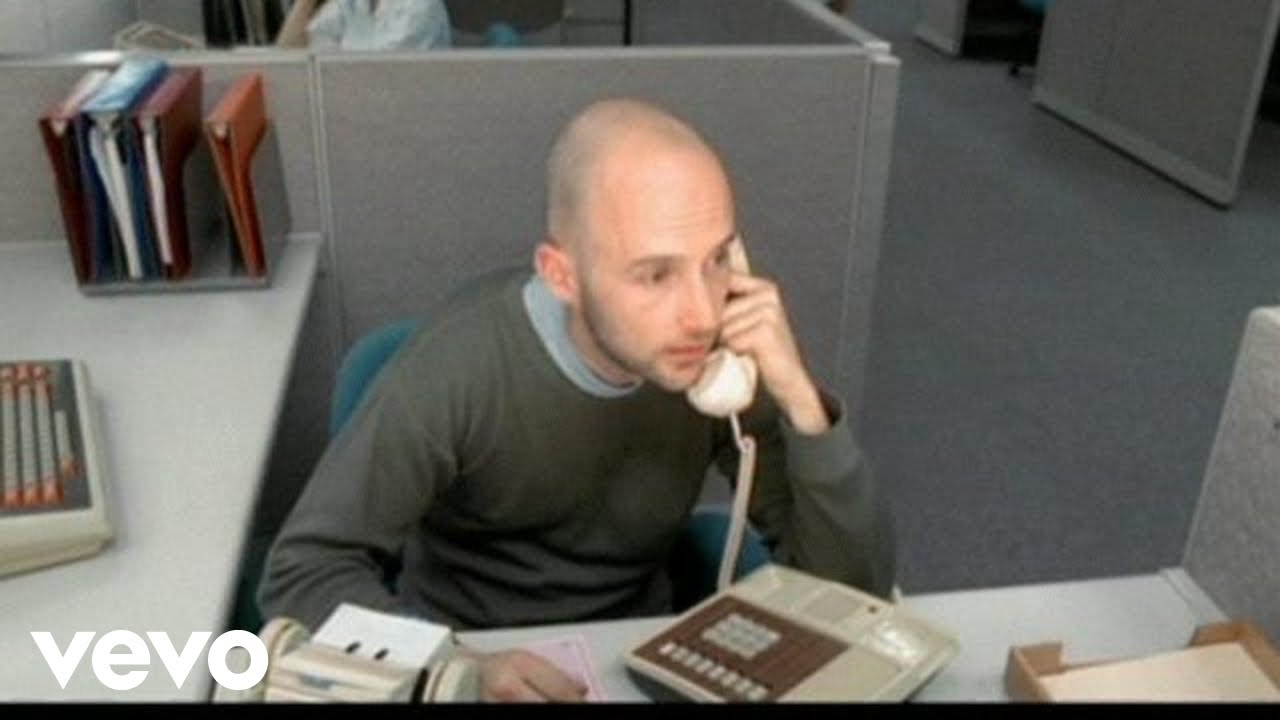

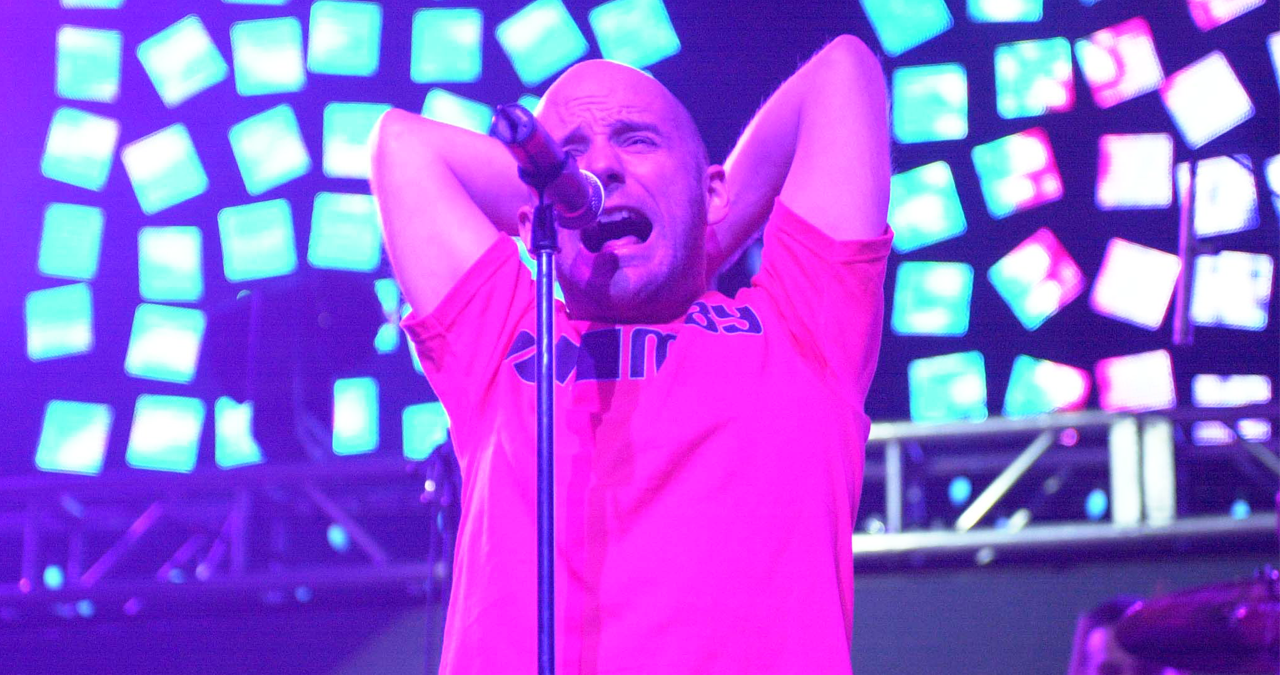

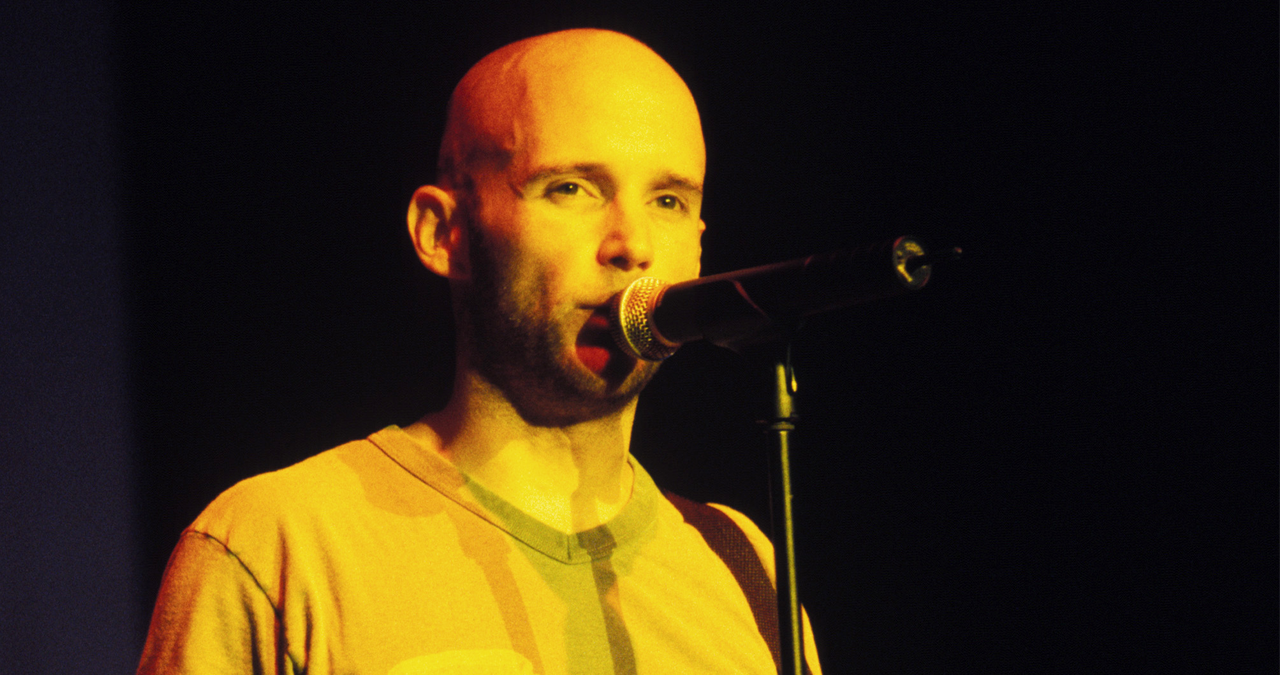

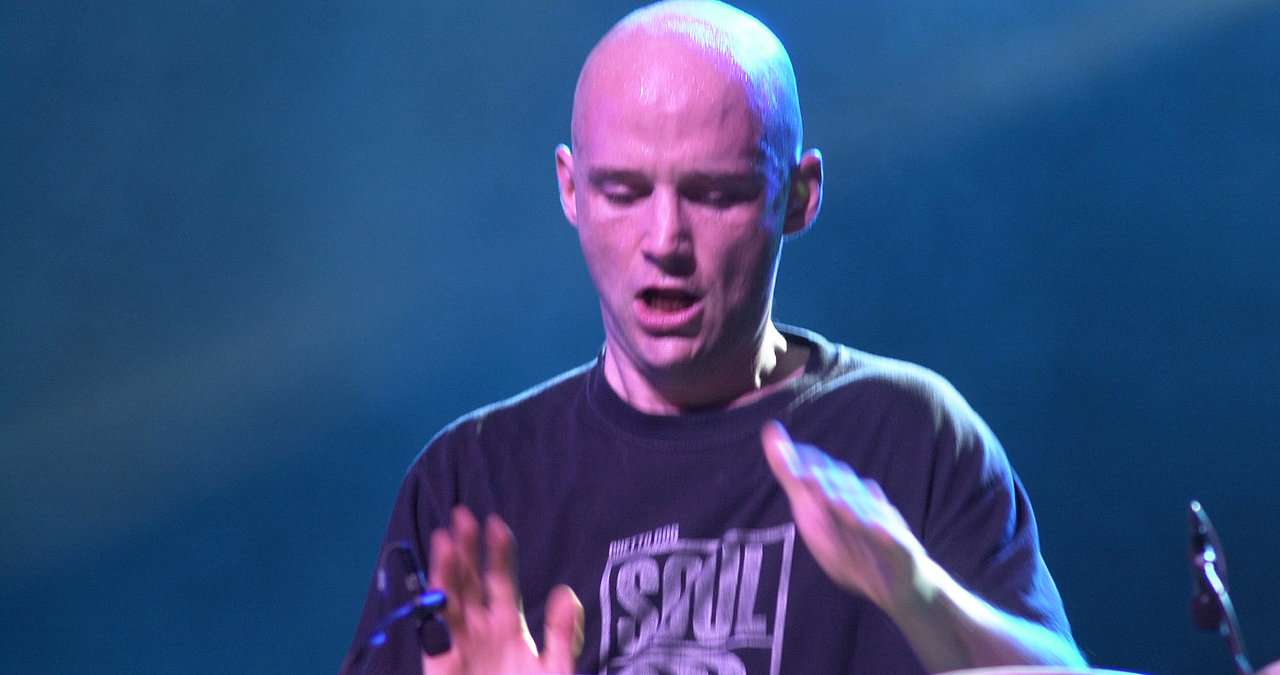

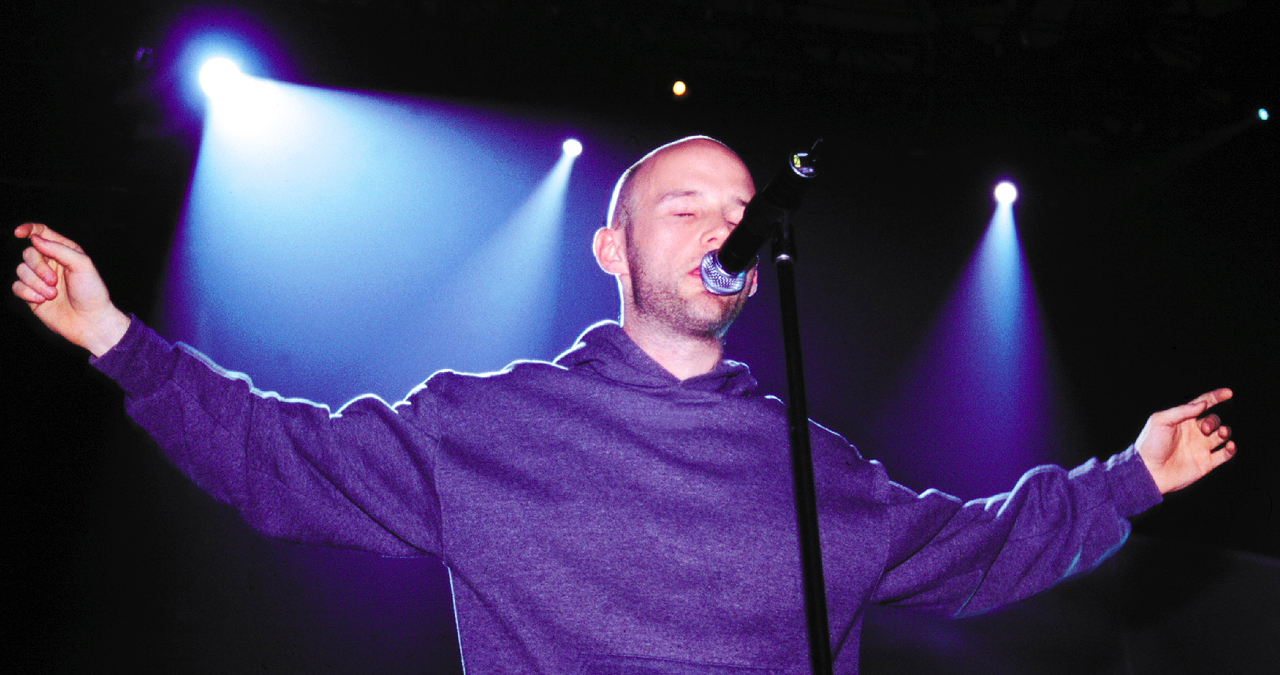

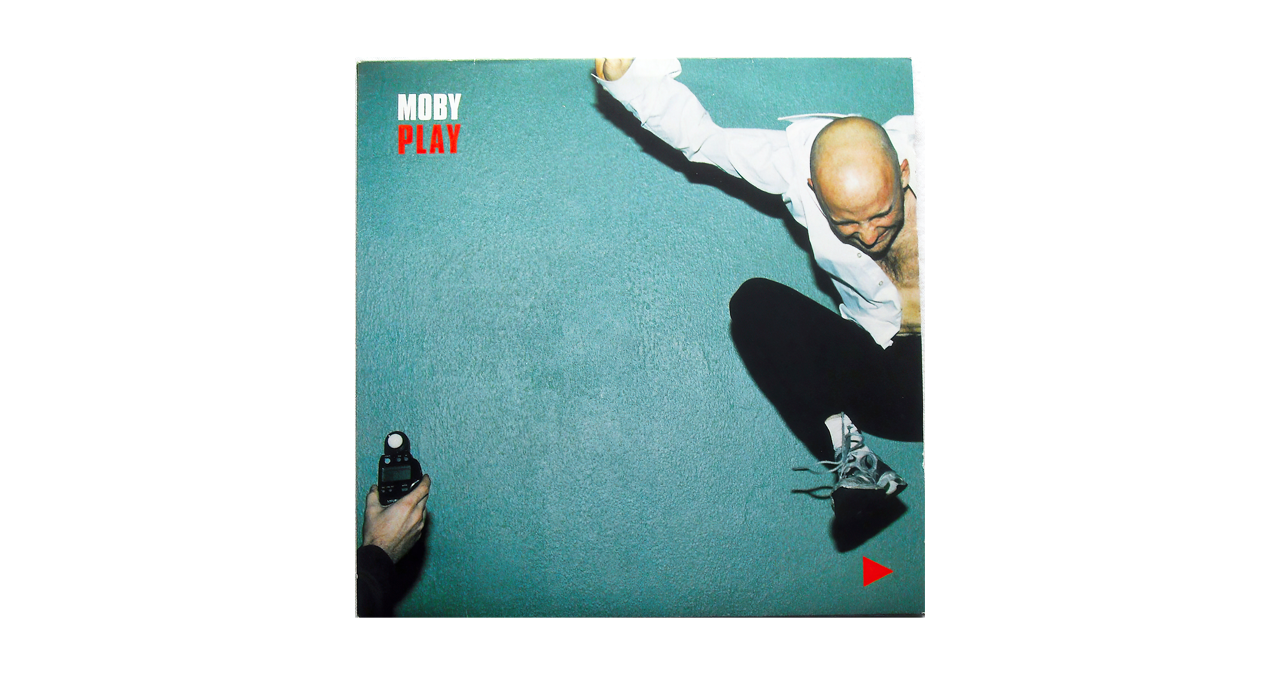

“When it was finished, I collapsed in exhaustion”: How Moby carefully crafted Play and rescued his career

Moby had all but thrown in the towel, but the surprising success of his eclectic 1999 masterpiece forever changed his fortunes

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Its tracks have graced innumerable adverts, trailers and soundtracks, but the emotion-stirring brilliance of Moby’s Play album was roundly ignored when first released back in May 1999.

Failing to chart at all in Moby’s native US, and landing at a paltry #33 in the UK album chart (where the lion’s share of Moby’s fanbase then resided) the man behind the literary-alluding monicker, Richard Melville Hall, had resigned himself to a depressing reality. It seemed that this diverse assortment of home studio-assembled tracks might just be the last hurrah of an ailing music career.

Ignoring the largely unfavourable reviews were those few who gave Play the benefit of the doubt in mid-1999, and discovered that, actually, it wasn't a shoddy record at all. Far, far from it.

They'd soon be proved right.

Though initially maligned, Play would, of course, become an inescapable phenomenon once propelled into the ears of the mainstream. It was smuggled into popular culture as a result of a canny decision to license its music across a wealth of advertisements and soundtracks.

Eventually topping the UK album charts (much to the astonished surprise of its creator) Play's staggering success would elevate Moby into the public conversation, leading him to become a respected elder statesman of electronic music's 21st century renaissance.

Well ahead of the advent of web-based sync-licensing agencies, Moby bypassed the traditional - and wholly disinterested - recording industry, and licensed every single track on Play for commercial usage.

It was an innovative tactic. But, this was a move facilitated by desperation above all else.

“The only interest we received was from people who wanted to licence the music for advertisements, TV and movies,” Moby told Billboard. “We kind of just said ‘Yes’ to almost everything, because it was the only sort of interest we were getting.”

This masterstroke exposed Play’s most pervasive cuts to those who'd never even heard of Moby - and perhaps had never even bought an electronic music record before.

Tracks were beamed into people's living rooms, tied to British commercials for Volkswagen, Nissan, Galaxy Chocolate, Rolling Rock and many, many more. Soon, television viewers couldn't shake these irrepressible ear-worms.

They liked what they heard, and they wanted more.

Over eleven months, Play's sales steadily increased from the initial 6,000 during the first week to an average 150,000 per week.

From techno-fiends to guitar-band obsessives and even people who just wanted some light dinner party accompaniment, Play became a regularly rotated CD.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But while this very modern exposure strategy was certainly pivotal to the record reaching a wider range of listeners, what really cemented its success was that the tracks in questions were, in a word, sublime.

“We kind of just said ‘Yes’ to almost everything, because it was the only sort of interest we were getting.”

Moby

Play is a tricky beast to characterise, primarily because it’s a record of (at least) two halves.

Most would consider the record’s soulful outriders, Natural Blues, Honey, Find My Baby and the glacial Porcelain to reflect the most notable sonic USP of the album.

These key tracks - all released as singles - were framed around haunting a cappella archive recordings, largely cribbed from folklorist Alan Lomax's collection of vintage field recordings, originally captured on open-reel tape during the 1940s to the 1960s

But that's by no means Play's singular hallmark. These tracks sit among the more hip-hop infused swagger of Bodyrock and the coruscating industrial EBM of Machete. Then there's a deluge of counterpoint vibes, from the reverb-swamped, downtempo drop-out of Down Slow and the bombastic pop strut of South Side.

But the most surprising cuts, for those who thought they had a handle on just who Moby was off the back of his advertising placements, were the sprinkling of lo-fi, demo-like songs that close out the album.

“The idea with Play is to have this narrative arc,” Moby told Rolling Stone in a fascinating track-by-track. “It starts off energetic and then by the end dissolves into an opiated haze.”

Play’s maker was born in Harlem, Manhattan in 1965, receiving the nickname 'Moby' from his father just three days after his birth. At age nine, Moby became entranced by music and began to learn classical guitar, before delving into jazz, music theory and percussion academically.

After a few teenage forays in noise-punk bands, Moby began to feel that the experimentalist end of the electronic music pool seemed a more inviting avenue.

Taking his childhood nickname as his artist identity, Moby embraced elements that spanned electronic music’s diverse plains, incorporating DJ techniques, synthesizer colours, distorted, fiery guitars and a creative application of sampling

A dedicated following in the UK helped get his 1991 - Twin Peaks soundtrack-sampling - single Go into the top ten of the charts.

“It starts off energetic and then by the end dissolves into an opiated haze.”

Moby

Despite this inventive early hit, Moby remained a niche figure throughout most of the 1990s, admired only by the electronica cognoscenti and his core fanbase.

Then came Animal Rights, a savage sonic rebuttal of everything that had come before, and a searing manifesto in favour of (you guessed it) animal rights.

A committed vegan since 1987, Moby poured his genuinely felt passion into this unexpectedly ferocious collection of thrash guitar-dominated tracks. However, rather than astounding his fans with his musical versatility, it left the techno crowd cold.

Animal Rights sold poorly, and received some of the worst reviews of his career to date. “Animal Rights was a self-indulgent record, very aggressive, just very self-indulgent,” Moby reflected in an interview with Chaos Control in 1999. The critics agreed.

A misjudgement then? Perhaps. But it’s inevitable that Play would be a very different record if not for Animal Rights’ near-career-ending failure.

The earliest work began on Play in the year following Animal Rights’ release in August 1997.

It was those Alan Lomax recordings we mentioned earlier that became an inspiring starting point. Moby was introduced to this archive when gifted a four-CD anthology by his friend Dimitri Ehrlich, entitled; 'Sounds Of The South: A Musical Journey From The Georgia Sea Islands To The Mississippi Delta'. These recordings had a reassuring impact on a disillusioned Moby - and were ripe to pilfered for musical ideas.

When affixed to insistent beats, sparkling piano, plaintive guitar and shards of synth-light, these haunting recordings came to life. These voices from the past became enmeshed with the sonic language of the present.

In contrast to its abrasive predecessor, the new material largely embraced a more meditative, downcast mood, perhaps informed by Moby's feeling that his career was nose-diving. Much of this new music was something that didn’t scream out for attention, but would reward those who leaned a little closer into its sparse textures.

“I wanted to make a record that’s emotional and personal,” Moby told Chaos Control. “Something that people could listen to in their daily lives and pay attention and find that rewarding or not pay attention to it and still have it be a nice record.”

Rome wasn’t built in a day, and nor was Play - taking around a year to assemble as Moby fulfilled touring obligations.

“I started work in August of 1997, went on tour for a month, then worked on it some more, then went on tour for a month and a half, worked on it more, did festivals, worked on it more,” Moby relayed in his Chaos Control interview. “So all together, you could say I worked on it for a year.”

Again, operating ahead of the curve in terms of approach, Play was entirely made in Moby’s small home studio in Mott Street, Manhattan.

Although modest in terms of quantity, Moby’s gear set-up was certainly non-too shabby in terms of its quality.

Synth-wise, Moby largely looked to a combination of Roland Jupiter-6 and Juno 106, as well as a Yamaha SY22 and SY35.

An Oberheim Matrix 1000 rack-mounted synth took pride of place in his rack cabinet, as did a series of Akai samplers (To be precise, an Akai S900, S1000, S3000XL and an additional S3000).

Further devices in Moby’s set-up included a series of Alesis ADAT units, an Eventide DSP4000 Harmonizer and a Yamaha TX802 FM Tone Generator.

Myriad other effects units and sonic curios peppered Moby’s small apartment, including a Voice Spectra Seekers Vocoder.

These details were derived from this discussion around a picture of Moby’s Play-era set-up shared to Reddit back in 2018.

Moby's home studio while recording PLAY, which turns 20 this month from r/synthesizers

“I wrote Honey in about 10 minutes."

Moby

“I hate having to learn how to use new equipment,” Moby told Chaos Control. “So I could get more stuff, but I hate the learning curve. So I try to be more comfortable with the stuff I’ve already got. Most of the equipment I’ve got now is the same stuff I had 5 years ago, or 7 years ago. I’ve got a few new things, I’ve upgraded the samplers. But synth-wise, I still use mainly older stuff.”

Concocted amid the (nearly 200!) tracks that Moby experimented with during the making the record were album highlights Porcelain, Bodyrock and Rushing - all of which ended up being not just being key songs on Play, but among the songs for which Moby would become most widely known as an artist.

Three of the new cuts, Find My Baby, Natural Blues and album opener Honey were derived from the Lomax recordings. The emotion-imbued, soulful vocals were core to their respective arrangements, and were easy to extract and work with due to their a cappella nature.

“I wrote Honey in about 10 minutes,” Moby recollected in Rolling Stone. “My girlfriend at the time really liked it. And that surprised me because she didn’t really like my music.”

Moby tethered the sample - a four-line vocal of blues singer Bessie Jones singing the song Sometime in 1960 - to a rhythmic piano and breakbeat pattern. In combination, these elements served to drill-in the gospel intensity of the original Jones vocal.

Using his collection of Akai samplers, Moby continued to mine from the Alan Lomax archive, digging out the starting points for Natural Blues and Find My Baby.

For these tracks, these core elements were a 1937 recording of folk singer Vera Hall singing the song Trouble So Hard and a 1959 recording of Boy Blue’s Joe Lee’s Rock respectively.

Emphasising the bluesy spirit of these original recordings, Moby furnished his musical backing with slide guitar and propulsive beats, infused with shades of the ambient and downtempo lexicon.

The original key sources of the samples that defined these three cuts can still be heard on The Lomax Digital Archive. A truly fascinating resource.

(Specific links - Honey, Find My Baby, Natural Blues).

“I was mainly listening to a lot of hip-hop,” Moby told PopMatters. “I wouldn’t expect anyone to hear a lot of hip-hop influence on [Play] but that was sort of what I was inspired by.”

Beyond the Fatboy Slim-adjacent swagger of Bodyrock, that hip-hop influence can certainly be detected in the crackly punch of the sampled loops that dominate the record, and Roland TR-909, 606, 707 and Alesis HR-16 beats that pepper the rhythm tracks. In particular, the 909's kick was something that Moby couldn't get enough of.

"Every record I made from 1990 until about 2000 featured the 909 in some capacity. Usually the kick drum," Moby told Dan LeRoy's Bonus Beats.

It wasn’t just the Lomax recordings that Moby relied on for samples. The impassioned main vocal sample that defined Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad? originated from The Banks Brothers’ He'll Roll Your Burdens Away (interestingly, they actually sang 'glad' and not 'bad'). So too did its 'He'll open doors' refrain of the song's second part.

Run On based itself around a 1949 recording by Bill Landford and the Landfordairs’ Run On for a Long Time.

“Run On was one of the first songs written and it was really hard to put together, because it has so many samples in it.” Moby recalled to Rolling Stone.

“I didn’t use computers at this point, it was all done with stand-alone samplers. When it was finished, I collapsed in exhaustion. I didn’t know this when I recorded it, but it’s a standard. Everybody’s done it. Elvis Presley did a version of it, Johnny Cash did it. If you were a gospel or country star, everyone covered that song. And I had no idea.”

Switching things up entirely was the vibrant pomp of South Side. Taking its cues from Moby's love of house music, its edgy lyric was couched in a hooky, chart-friendly aesthetic.

Moby asked his friend, No Doubt’s front-woman Gwen Stefani, to supply a lead vocal. Recorded within his Manhattan apartment, Moby just couldn’t get her vocals to sit right in the mix, leading to her contribution being removed from the album version.

Thankfully, Stefani's vocals were re-instated for the eventual single release (which would be accompanied by a memorable video). However, the track was destined to become Moby’s least favourite on the album.

But while the sample-based work would be the record's most well-known, its threadbare finale - including the bucolic Guitar Flute & String and the thinly-recorded Everloving - were added to Play during a particular period of hopelessness.

“[Guitar Flute & String is] my favourite song on the whole record. Hands down, bar none,” Moby told Rolling Stone. “When Play was released, I didn’t think anyone was gonna listen to it. So I figured towards the end, I will put on the songs that I like. No one’s gonna listen to this record, certainly no one’s ever gonna get this far in the record. Track 15 or whatever? So I put it on there for myself."

For most listeners, the track that would (eventually) be cited as the record's standout, and one of the most iconic electronic tracks of all time, was Porcelain.

Characterised by the enveloping warmth of its string pad, Porcelain felt like an aural hug. It shifted through a four-chord progression (Gm, Bb, Fm and Ab) and was, somehow, both widescreen and intimate at the same time.

Porcelain's glistening piano notes, and a mysterious vocal sample (which one Reddit user seems to have isolated as being from 'Let Their Voices Be Heard: Traditional Singing from South Africa') worked beautifully in tandem.

Its cinematic flavour would ultimately prove a certified no-brainer for commercial licensing. The calming potency of Porcelain would be globally recognised after being used for advertisements spanning Volkswagen, Bosch, Polo and France Telecom, as well as on the soundtrack for Danny Boyle’s The Beach.

With the record nearing completion, Moby grew dissatisfied with his own mix and went to various different mix engineers to try to get Play into a release-able state.

“I mixed it [in my home studio], then I wasn’t happy with it, then I went to one outside studio to mix it, went to another outside studio, another outside studio to mix it and then I ended up coming back here and doing the mixing myself. So I wasted a lot of time and money,” Moby recalled to Chaos Control.

Of its simple, to the point, title, Moby relayed to Nada Mucho how he was inspired by seeing the word on a nearby wall.

“This album I wanted a nice simple title. There is this school right near my house and they have a playground. And on the wall painted in giant letters like 10 feet tall and 40 feet wide, it says 'play'. I saw it every day, and it kind of started to percolate into my conscience.”

Eventually satisfied with the mix, releasing the album at all was the next hurdle. After Animal Rights, US label Elektra had quietly dropped Moby, while UK label Mute begrudgingly still backed their unpredictable polymath.

Moby shopped the album around to several major labels - all of whom turned down the offer to distribute what they calculated would be yet another bizarre commercial failure. Thankfully, Virgin Records’ founder Richard Branson’s second record label incarnation, V2, agreed to take a punt on Play.

“I’m a strange artist. I’m not a singer/songwriter, I’m not a hip hop artist, I’m not a R&B artist, I’m not a country artist. So, I shouldn’t be on a major label,” Moby explained to Chaos Control.

And what happened next was… initially nothing.

With a piddling promotional spend, Moby took it upon himself to personally harangue press contacts and radio stations for exposure.

But getting Play some attention was often more trouble than it was worth.

“Back then I paid tons of attention to everything,” Moby told Ticketmaster. “I would go to the newsstand and find anything written about me, and I was completely narcissistically self-involved. I read all the reviews, and if memory serves, there was only one good one. All the others were either dismissive or scathing, and in a lot of cases they just opted not to review the record because I was such a marginal figure.”

But, as we outlined at the beginning of this article, Play had quite the remarkable second wind.

Thanks largely to his industry-countering inclination to offer-up his music to the commercial universe, Play’s songs began to seep into the collective consciousness. It led Moby, who had considered quitting his music career should the album flop, to became the most unlikely of household names.

Now hailed as an outright classic on its own merits, Play stands tall as a sonically striking work - temporally dislocated as a result of its sample-heavy construction, yet forward-facing in both its inventiveness and ever-shifting mood.

It prefigured the self-driven music industry that would become the norm once once the web age took root, with artists seeking alternatives to the traditional record label promo funnel.

Co-opting visual media to get his songs heard, Moby anticipated today's social media-angled drive to associate music with viral, repeatedly-watched video content.

Play still sports two impressive accolades - it’s the biggest selling electronic music album of all time with over 12 million copies sold, and also the record whose songs have been the most licensed for commercial use in history.

Despite its massive slow-burn success and cultural footprint, its forthright creator remains lukewarm on the record that made him globally famous.

“I thought [Play] was too eclectic. It was recorded in a bedroom with really mediocre equipment,” Moby told The Independent. “The fact that it became as successful as it did is still baffling. Listening to it now, I realise I don’t really like the first half of the album, and I only like the second half, which is the weird, experimental, dissonant part I don’t think anyone’s actually listened to.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.