How Burial used a "rubbish, dying computer” and primitive audio editing software to make one of the most influential electronic albums of all time

A prime example of how the less-is-more philosophy can fuel creativity, Burial’s extraordinary 2007 masterpiece Untrue was created entirely within Sony’s antiquated Sound Forge

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Self-limiting himself to just one piece of basic audio editing software - and a computer that could barely muster the processing power to run it - Burial (real name William Emmanuel Bevan) unlocked the darkly-hued vibes of his seminal second album Untrue.

Gaining traction on the back of his intriguing 2005 EP, South London Boroughs, and his impactful self-titled debut released later that year, it was the mood-driven 2007 follow-up Untrue that cemented Burial as one of electronic music’s most compelling figures.

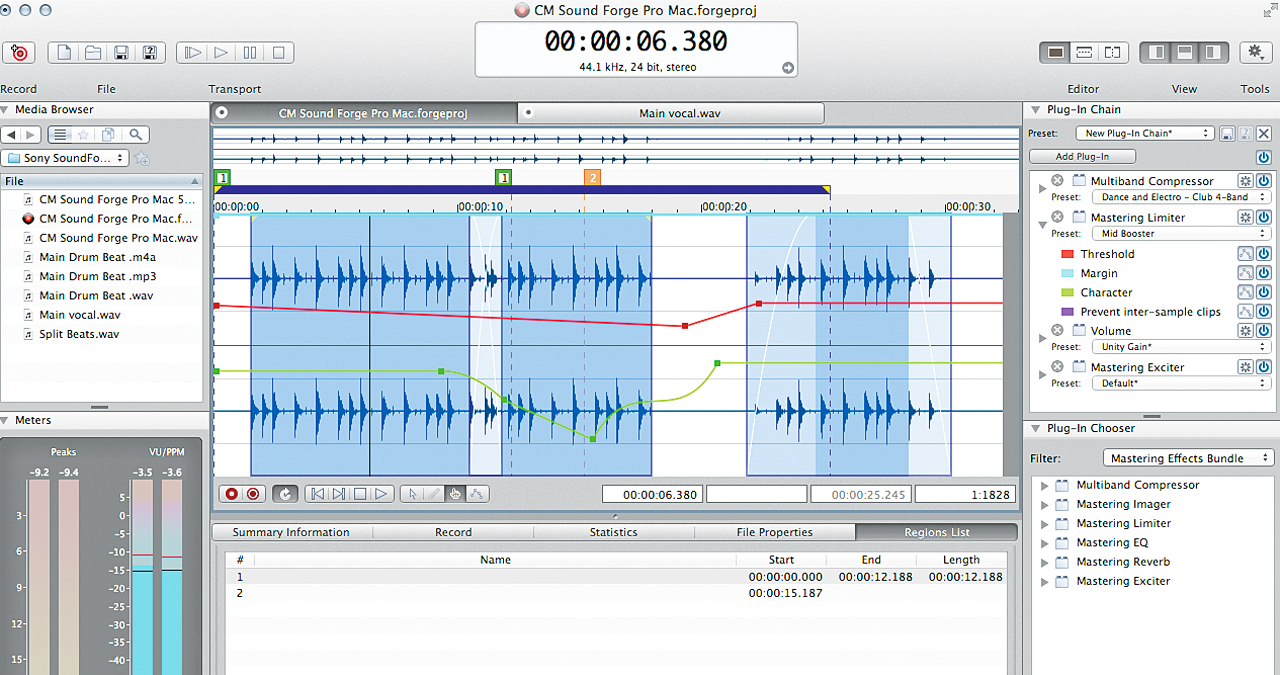

It's truly staggering to learn that this sublime album was meticulously built within early audio editing software Sound Forge. This legacy waveform editor was incredibly basic in comparison to its more advanced, music production-focussed successors.

“I wish sometimes that I’d gone to college to learn music production, but other times I’m like ‘no, f**k, I’m happy I didn’t’”, he admitted to The Wire.

First launched by Sonic Foundry in 1993, the software was eventually sold to Sony in 2003. It was this later Sony-branded version that Bevan used to craft Untrue.

Melding disparate shades of proto-dubstep, skittering beats, cavernous reverb and slick downtempo, Burial’s sonic universe burrowed into the aural language of loneliness - eliciting visions of cold and unfeeling city streets and looming, liminal environments. It was a prime example of the 'hauntology' aesthetic.

Pressure to learn more about some more high-end music production kit by his industry peers only served to drive the 27 year-old William more tightly into Sound Forge’s comforting arms.

“I thought to myself f**k it, I’m going to stick to this shitty little computer program, Soundforge [sic],” Burial said in a Q&A around Untrue’s release. “I don’t know any other programs. Once I change something, I can never un-change it. I can only see the waves. So I know when I’m happy with my drums because they look like a nice fishbone. When they look just skeletal as f**k in front of me, and so I know they’ll sound good.”

Essentially a single-track, waveform-based digital audio editor, Sound Forge regarded each individual stereo or mono audio file as its own project - but allowed for deeper tweaking, stretching and pitch-shifting for each of Burial’s samples or recorded starting points.

However, as he indicated, these changes were often destructive and couldn’t be quickly undone (as is the norm in most modern audio software).

Burial would build up an entire track’s project as effectively one large waveform - throwing additional elements into the main project window, these were timed by ear as opposed to relying on a click or grid.

Making an album with Sound Forge was, therefore, laborious work - and Burial would spend long nights carefully sequencing his sounds by-ear to get them sounding how he wanted them.

Typically soaking his audio with Sound Forge's in-built reverb effect, Burial’s approach had no roadmap, and he’d often have to ‘feel-out’ the direction of travel towards completing each track.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Any dead space would typically be filled by vinyl and tape crackle or smeared, ambient textures. “Everyone goes on about vinyl crackle, but I love tape crackle, that’s a beautiful sound,” Burial told The Guardian. “I just like tunes to be as atmospheric as f**k, I don’t like that clean sound. I don’t see the point of that clean sound, it’s so neutral.”

In his bag of collected sounds were, notably, samples cribbed from, PlayStation game, Metal Gear Solid’s sound effects (in particular, bullet casings dropping on the ground) and extracts from films. These were then wrangled to taste within Sound Forge.

The project was clearly audacious. Why then, did he stubbornly rely on this, rather basic, audio editing tool as opposed to a more professional-sounding DAW or traditional sequencer?

“I admire people who understand complicated programs or whatever,” Burial explained to Kode9. “But I'm not that into tunes that are so sequenced that all you can hear is the perfect grid, even on the echoes. With those kind of tunes, sometimes I just hear Tetris music.”

Fuelled by the wooden floorboard-like feel of its dust-covered drum sound, and interwoven with vocal samples, desperately grappling for the track’s faltering central melody, Untrue’s most celebrated track, Archangel, exemplified his instinct-driven methodology perfectly.

This was abstract, yet hugely affecting music that demanded that listeners unshackle their preconceptions and wallow in its prismic textures, which eventually open up onto a more spacious plane.

The interplay between the spectral, often eerie, vocals and its un-synchronised, organic beats were an essential artistic consideration.

“Mates laugh at me because I like whale songs but I love ‘em,” Burial told The Wire. “I like vocals to be like that, like a night cry, an angel animal. Old hardcore tunes would throw these sounds in, anything to create the rush, descent into another world. So I had to do that, but have cut-up vocals and have that slinky bumping feel to it, and not get weighed down in big drums and the big snares.”

Conceived in just 20 minutes, Archangel was perhaps the most purposeful attempt to subvert that external pressure to strive toward perfection.

As recounted in Mark Fisher’s Ghosts Of My Life, Burial stated, “I was worrying. I’d made all these dark tunes and I played them to my mum and she didn’t like them. I was going to give up, but she was sweet, telling me ‘Just do a tune, f**k everyone off, don’t worry about it.’ My dog died and I was totally gutted about that. She was just like ‘Make a tune, cheer up, stay up late, make a cup of tea’, And I rang her mobile just 20 minutes later and I’d made [Archangel]. I was like, ‘I’ve made the tune, the tune you told me to make.’"

Beyond Archangel, Untrue’s most soul-touching moments - the pained regret of the pressure-driven Near Dark, the near-tangible world-building of the ethereal In McDonalds, and the divine bittersweet conclusion of Shell of Light - would undoubtedly be wholly different beasts had Burial strove for ‘perfection’.

Burial rejected smooth, quantised and edgeless production for an ethos that was unrefined, but undoubtedly purer in spirit.

The basic functionality of Sound Forge was, therefore, the perfect tool for the project.

Beats and grooves were, delightfully, off-grid. “Because I don't have a sequencer I can't really mess around. I can't noodle, at all,” Burial said in a Q&A with journalist and producer Blackdown around Untrue’s release.

“I got to shove it together and vibe off it. I make the tune, f**king quick. Not a single tune on my album took more than a few days to make. They come together real quick and then I spend some time on the details so they're alright to listen to.”

As Sound Forge wasn’t a traditional DAW as such - and samples weren’t as widely available as they are in today’s marketplace - Burial fashioned many of the source sounds for his beats from an plethora of self-recorded twangs, hits, clanks and impacts from surfaces and textures around his own home.

Burial then processed these recorded sounds in Sound Forge, emphasising their rhythmic potential and shaping them into forms that at least partially resembled real kits.

The distinctive flavour of these insistent rhythms, therefore, would sound massively different if they had been created using loops, a sequencer or a more advanced DAW.

“The drums are more about trying to thread sounds and vocals together, they flicker across the surface of the tune,” Burial explained to The Wire. “It circles around you, its not just chopping you up, its not about the sounds being big.”

Entirely comfortable with his modest set-up, Burial’s most pressing consideration when readying himself to produce music was tuning himself into the appropriate headspace to embark on his creative flow state.

This was typically at night.

“I would literally sit around waiting for night to fall. I don’t want to be a wall-starer, y’know staring at walls, but I would be waiting for night-time, thinking ‘I really want to make some good tunes tonight,’” Burial told The Guardian.

“Or I would go out walking, wait for it to get dark, and then I’d go back… I love that feeling when you know that almost everyone in the city is asleep. That’s got to be the only time to work.”

But this wasn't the sort of work that was undertook with headphones clamped to Burial's head, or within a heavily-treated home studio either. Burial had to live within the vibe he sought to reflect in his music.

"The tunes are made where they’re made, somewhere in my building, the roof or wherever, but not in some airtight studio. Loads of the album was made with the TV on," he told Kode9.

Burial embraced the shoddiness of his set-up, making the imperfections a driving force. "I wanted to do a tribute to my rubbish, dying computer. It starts smoking sometimes and the screen flickers like a strobe-light, it mashes your eyes."

Now regarded as a modern masterpiece, Untrue’s idiosyncratic production story only heightens our appreciation for it.

Infamously low-profile, Burial remains a mysterious figure. But, never performing live and rarely giving interviews hasn’t stopped his influence permeating the electronic music world.

The chief learn to take from the story of Untrue, is that the ‘best’ tech for making music at any one time is often not necessarily the best choice for any singular working creative.

“It’s almost like I’m trying to make that imperfect record, before I learn how to go away and do it properly,” Burial told The Guardian following the record’s release. “I want to make these more DIY tracks. I was never really expecting so many people to hear my record.”

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.