John Bonham considered him 'a god' and Buddy Rich called him 'the inspiration for every big-name drummer in the business': The story of Gene Krupa, the king of swing

Krupa was "a dazzling blitzkrieg of cymbal and snare drum violence", and one of the most influential drummers ever

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Carnegie Hall, 1938

DRUMS WEEK 2025: Carnegie Hall, New York City, 16 January 1938. An eager audience is keyed up with excitement, awaiting the first jazz concert at this prestigious classical music venue.

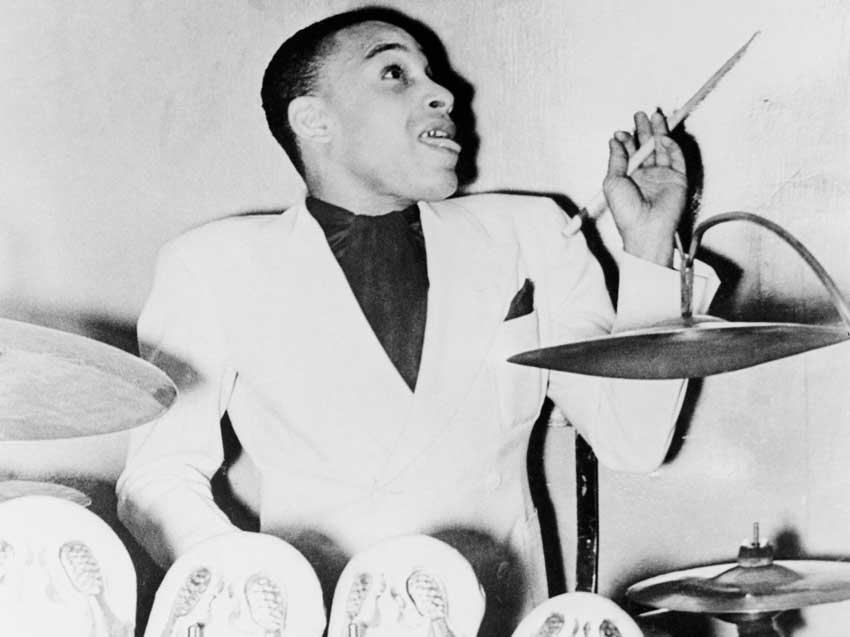

At one time every drummer in the world wanted to play like Gene Krupa

Buddy Rich

The Benny Goodman Band launch into their opening number, ‘Don’t Be That Way’. The drummer pushes the beat with urgent press rolls, but the band are edgy, afraid of cutting loose.

Then comes a split-second drum break, a dazzling blitzkrieg of cymbal and snare drum violence, hotly pursued by a battering offbeat. The audience immediately goes wild. Even the musicians yell encouragement. Gene Krupa has broken the ice and worked his percussive magic. Swing is here!

The man who electrified that celebrated Benny Goodman concert became the most famous drummer in the world. As well as being an innovative soloist, armed with tremendous speed and stamina, Gene Krupa was a charismatic figure. Fans were thrilled by the tousle-haired, gum-chewing drummin’ man with movie star good looks.

Gene was always an extrovert who hit hard and played loud. As a teenager, he insisted on his bass drum being recorded, even when engineers thought it was impossible

Gene was always an extrovert who hit hard and played loud. As a teenager, he insisted on his bass drum being recorded, even when engineers thought it was impossible. When he played ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ with the Benny Goodman Band, his roaring tom-toms rekindled the African spirit of jazz. Drummers from Buddy Rich to John Bonham idolised Krupa, and his influence was felt well beyond the swing era.

Gene’s playing career spanned five decades of jazz history, but it wasn’t until he joined Benny Goodman’s band in late 1934 that his fame began to spread. The Krupa story became an explosive mix of ego clashes and dramatic incidents.

Frequent onstage rows with Goodman and a heavily publicised drugs bust were just some of the incidents that put him in the headlines. Yet Krupa was far from being the ‘drug crazed jazz fiend’ the press tried to portray. He was dignified, quietly religious, proud of his achievements and sensitive to criticism.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The early years

Gene Krupa was born in Chicago on 15 January, 1909, the youngest of six children. Brought up a Catholic, Gene’s mother wanted him to become a priest. However, at the age of 10 he took a part-time job as an errand boy in a local music store. Growing up on Chicago’s notoriously tough South Side, he could have got caught up in the local street gangs.

Instead, he listened to all the latest jazz records in the store, took up the alto sax and began playing with The Frivolians, a high school junior band. One night, after a rehearsal, he tried out the band’s drum kit. It was then that he decided he’d much sooner play the drums than the saxophone. He showed such ability that his older brother Pete bought him a set of traps.

Gene grew up listening to the New Orleans drummers and the enthusiastic young local musicians playing Chicago-style jazz, like sax player Bud Freeman and drummer Dave Tough. When Tough left his band, The Blue Friars, Gene was offered the gig. At last he could play regularly with a real jazz band. Although self-taught, he took advice from Dave Tough on tuning the drums, choosing the right cymbals and playing them tonally to complement the instruments in the band.

He also studied hand-to-hand press rolls, as performed by the New Orleans drummers. In 1925 he took lessons from drum teacher Roy C Knapp and joined the musicians union. Now he could play in bars and clubs like the Three Deuces, where gangsters often engaged in gunplay and fights broke out.

One of the regulars who jammed at the club was teenage clarinet prodigy Benny Goodman. Gene teamed up with the McKenzie-Condon Chicagoans for a recording date, and it wasn’t long before many of the Chicagoans, including guitarist Eddie Condon, Benny Goodman and Gene headed for the Big Apple. Gigs were hard to come by, but Gene found work in theatres and rapidly began to build up a strong reputation.

In January 1930, Krupa played alongside Glenn Miller in the orchestra for the Broadway show Strike Up The Band. Gene couldn’t read the drum score and Glenn had to help him out by humming the parts. Gene was determined to learn how to read. He took lessons with Sanford E Moeller – the finest teacher in New York – and also learnt how to use his arms in a flailing motion to add more power.

It was this combination of power and visual appeal that made him so popular. Composer George Gershwin pronounced Krupa his favourite show drummer. Said Gene later, “I didn’t have the right technique. I resolved to learn the drums from the bottom up. I used to practise seven hours a day.”

A big influence on Gene was the contrapuntal playing of Vishnudrass Shirali, who played 12 drums for Hindu dancer Uday Shan-Kar. Krupa also heard African drumming on recordings made by explorers in the Belgian Congo.

Years later, when he became the leader of his own big band, he would give each musician a small tom-tom to play. And one young drummer who saw the Krupa Band beating out African-style cross-rhythms was none other than Max Roach.

In 1932, Gene was booked to play with crooner Russ Colombo’s band. The ‘fixer’ turned out to be Benny Goodman, who insisted that Krupa only play wire brushes. The restriction infuriated the drummer. He told A&R man John Hammond: “I’ll never work for that son of a bitch again!”

By 1934 Gene was working for a ‘commercial’ band in Chicago, which at least provided a regular income. Back in New York, Goodman was planning an exciting new band and desperately wanted Krupa to join. Gene was the only man who could really make it swing.

John Hammond (who much later discovered Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen) enticed Krupa back from Chicago, explaining that Benny’s new band would be playing top arrangements by Fletcher Henderson. After a particularly dull gig, Krupa agreed to join the new Benny Goodman Orchestra in December 1934. The band began making regular appearances on a live radio show.

The show, Let’s Dance, was heard from coast to coast and these broadcasts sowed the seeds of acceptance for swing music. Armed with trumpet soloists Ziggy Elman and Harry James, the band developed an attacking sound of its own. On the road, they often developed ‘head arrangements’ – one of the most famous was ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ which developed into a marathon epic built around Gene’s dramatic tom rhythms.

As well as sparking the big band, Krupa also drove The Benny Goodman Trio and Quartet, the latter featuring vibraphone genius Lionel Hampton. The small groups made dozens of exciting recordings, with Gene blowing up a storm with sticks and wire brushes on tunes like ‘Dizzy Spells’, ‘China Boy’ and ‘Runnin’ Wild’.

Swing, Swing, Swing

At first the brash Goodman-Krupa sound shocked ballroom managers, who threatened to cancel gigs and demanded their money back. A nationwide tour seemed doomed to failure, and Goodman was on the verge of packing up. Krupa urged him to keep going.

When the band arrived at the Palomar Ballroom, Los Angeles, an audience of college kids gave them an ovation. When they played the Paramount Theatre in New York in March 1937, 3,000 fans danced in the aisles, while another 3,000 tried to get in. The 1938 Carnegie Hall concert saw the drummer get almost as much hero worship as the leader.

The clarinettist began to resent the way audiences cheered and applauded Krupa and Goodman began to restrict Krupa’s solos, ordering him to play brushes instead of sticks and looking bored on stage while Krupa was playing. They couldn’t even agree over the tempos. The row went on for several shows, with both men arguing in public. Eventually, Krupa quit the band.

Within weeks he had formed the Gene Krupa Orchestra, signed to MCA and made his debut at the Steel Pier ballroom in Atlantic City, on 16 April 1938. The new band went down a storm in front of 4,000 fans. His band was hugely popular and became even hotter when the added Anita O’Day and Roy Eldridge in 1941.

The trumpet player had recorded several sides with Krupa in the ’30s including ‘I Hope Gabriel Likes My Music’ and ‘Swing Is Here’. It wasn’t long before The Krupa Band was hitting the charts with ‘Drummin’ Man’ and ‘Drum Boogie’. Gene and Anita also cooked up hip vocal and instrumental numbers like ‘Let Me Off Up Town’ and ‘Bolero At The Savoy’, while Gene was showcased on ‘Wire Brush Stomp’ and ‘Blue Rhythm Fantasy’.

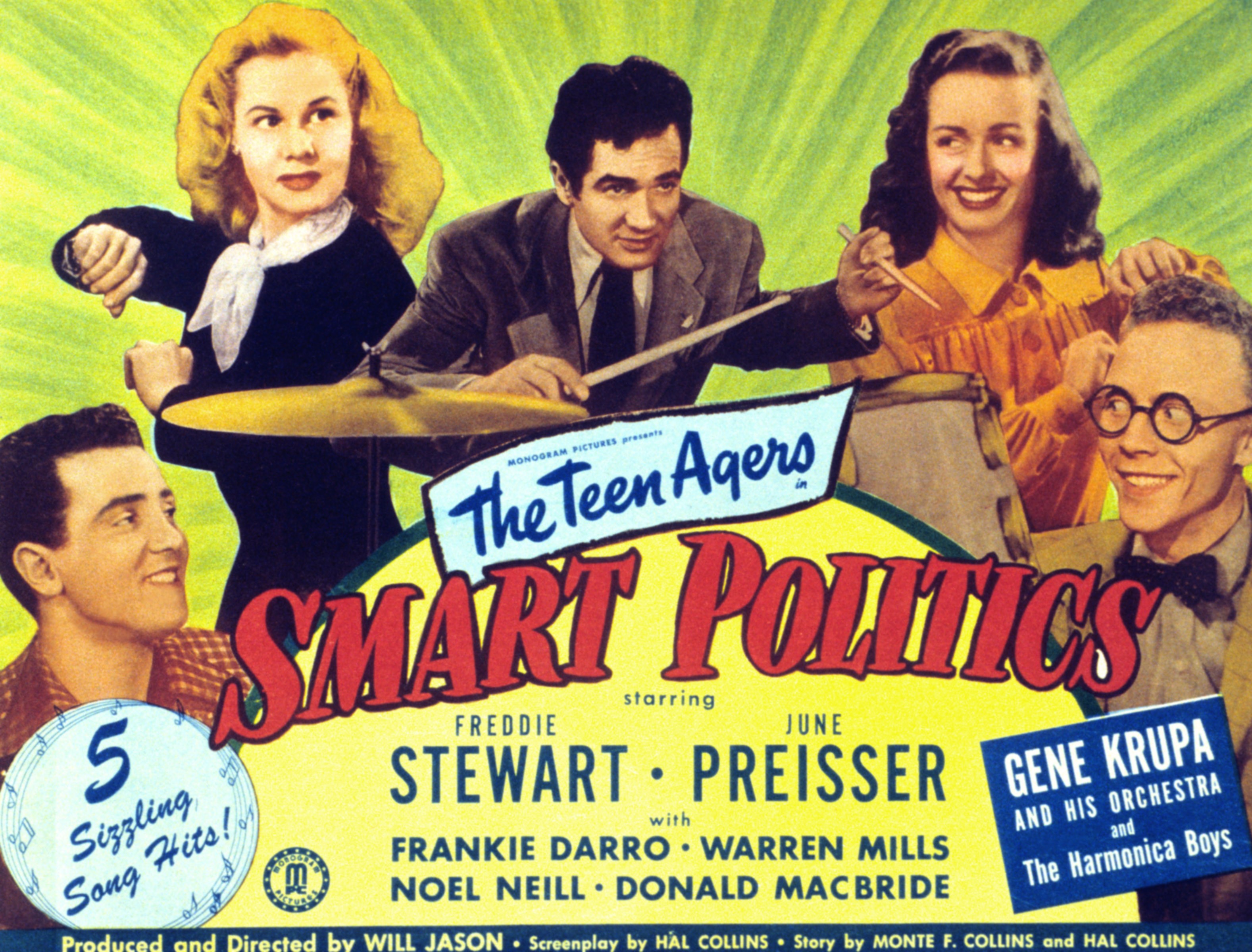

Such was his popularity, Hollywood beckoned. Krupa showed his ability as an actor and was able to deliver lines with ease, notably in Bob Hope’s 1938 movie Some Like It Hot and in 1941’s Ball Of Fire with Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck.

In one scene, Gene plays paradiddles on a match box with a pair of matches. On the last beat, he strikes them with a flourish and they burst into flame. It was a neat trick that thrilled wartime movie audiences.

Fall and rise

Despite all his public success, Gene’s personal life was in turmoil. He split with his wife Ethel in 1941 and had to pay her a settlement of $100,000. Worse was to come. In 1943, Gene fell victim to a drugs bust that almost ruined his career. He endured two trials and an 84-day jail term which shattered him.

The drugs issue was grossly exaggerated and the effects of the imprisonment and bad publicity were a source of great distress. In August 1943 he was released on bail, pending an appeal, and finally freed when the charges were dropped.

Gene felt like giving up appearing in public after the experience, and planned to teach and write music. The jail sentence had ruined Krupa, but it brought about a reconciliation with Ethel. She helped him out financially and they remarried in 1947. He was even offered his old job back with Benny Goodman and he returned to the stage in September 1943.

He was grateful to Benny, but switched to Tommy Dorsey’s band rather than risk a nationwide Goodman tour where he might be greeted by placard-waving moralists.

Krupa burst into tears. But he was back behind a kit of drums, where he belonged.

When he sneaked onstage at the Paramount Theatre with Dorsey, fans recognised him and cheered. Krupa burst into tears. But he was back behind a kit of drums, where he belonged. It wasn’t long before Gene formed another band of his own in 1944. Inspired by Dorsey, Gene added a 10-piece string section and even brought in another drummer to play while he conducted.

This idea didn’t go down too well with fans or the press and Gene got fed up, especially when the strings couldn’t keep in tune with the brass. He finally returned to a regular band in the summer of 1945.

By 1946, bebop was spreading beyond New York’s 52nd Street clubs. Gene listened to the new music being played by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and accepted the need for change. He brought in bop trumpeter Red Rodney and featured modern arrangements by Eddie Finckel and Gerry Mulligan on tunes like ‘Bird House’, ‘Disc Jockey Jump’ and ‘Up And Atom’.

Gene worked surprisingly well in this context and soloed effectively on ‘Lover’ and ‘Higher Than The Moon’. On one of his best numbers, ‘Leave Us Leap’, he utilised the ‘freeze beat’, a trick Krupa had picked up playing for dancers.

Krupa kept his band going until 1951, but crooners and rhythm and blues were ousting big bands. At one stage, in desperation, he began to play country and western music, although his musicians rebelled and threatened to quit.

The band finally broke up and Gene began touring with tenor saxophonist Charlie Ventura, playing heavily-stylised versions of tunes like ‘Dark Eyes’, ‘St Louis Blues’ and ‘Body And Soul’. Although often panned by the critics for being too showy, their trio was enormously popular.

In the ’50s Gene joined Norman Granz’s Jazz At The Philharmonic touring troupe. He was featured with a quartet and often engaged in drum battles with Buddy Rich. His playing on these dates was increasingly erratic and lacked control. In March 1953 Gene came to Britain with Jazz At The Phil for a special flood relief concert.

They played at the Gaumont State, Kilburn and the late jazz writer Benny Green recalled the show. “Nobody who saw the concert will forget the sight of Krupa, dwarfed by his own giant shadow behind him, playing like a man possessed.”

In 1954 Gene set up a drum school with Cozy Cole in New York and also went on a tour of Australia. The following year he filmed a guest appearance in The Glenn Miller Story playing alongside Cozy Cole in a jam session with Louis Armstrong on ‘Basin Street Blues’. Hollywood duly attempted to equal the success of this biopic by making The Benny Goodman Story. This entailed a reunion with Goodman, and Gene reprised his solo on ‘Sing, Sing, Sing’ for the movie’s soundtrack.

In 1959 the drummer was portrayed by Sal Mineo in another Hollywood film Drum Crazy, The Gene Krupa Story. Sal made a good stab at the role and a fascinating promo film made at the time showed the two drummers rehearsing and jamming together. However, the movie was full of anachronisms and has since fallen into obscurity. It depicted Gene as a crazy guy, prone to dropping his sticks and smashing up his drums. Astonishingly there was no reference to Benny Goodman (due to contractual reasons), which made it impossible to feature many of the highlights of Gene’s own career.

The show goes on

In 1960 Gene had a heart attack and doctors warned him to take life more easily. Typically he carried on playing and recorded an excellent album with Charlie Ventura, The New Gene Krupa Quartet in 1964. He also toured Japan, Mexico and South America. In 1967 he said he felt ‘lousy’ and admitted his playing wasn’t so hot. After a period of retirement, he was reunited with the original members of the Benny Goodman Quartet for an album called Together Again.

During most of the ’60s Gene played with his quartet at the Metropole Bar in New York. One night, Benny Goodman dropped in unannounced and sat in without being invited. “Brushes, please…” said BG. Gene went white with fury but played as he was bidden.

Gene’s last gigs with The Benny Goodman Quartet were in 1973. They included a return appearance at Carnegie Hall as part of the Newport Jazz Festival. Although Gene played with all the energy at his command, he was clearly very ill. A hospital check revealed he was suffering from leukaemia and he had to undergo a course of blood transfusions and chemotherapy.

As if this wasn’t bad enough, early in 1973 Gene’s home in Yonkers was badly damaged by fire. All of his precious records, tapes, drums and memorabilia from a lifetime in music was destroyed in the blaze.

The last performance by the Goodman Quartet was in Saratoga Springs, New York on 18 August 1973. Two months later, on 16 October 1973, Gene Krupa died at home in bed at the age of 64.

Tributes poured in from fellow drummers, but it was left to his old sparring partner Buddy Rich to put his contribution into perspective. “Gene was the inspiration for every big-name drummer in the business. At one time every drummer in the world wanted to play like Gene Krupa.”

A suitably adept appraisal of Gene’s enormous influence as a man, an icon and, above all else, a true rhythm king.

Geoff Nicholls is a musician, journalist, author and lecturer based in London. He co-wrote, co-presented and played drums on both series of ‘Rockschool’ for BBC2 in the 1980s. Before that he was a member of original bands signed by Decca, RCA, EMI and more. ‘Rockschool’ led to a parallel career writing articles for many publications, from the Guardian to Mojo, but most notably Rhythm magazine, for which he was the longest serving and most diverse contributor.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.