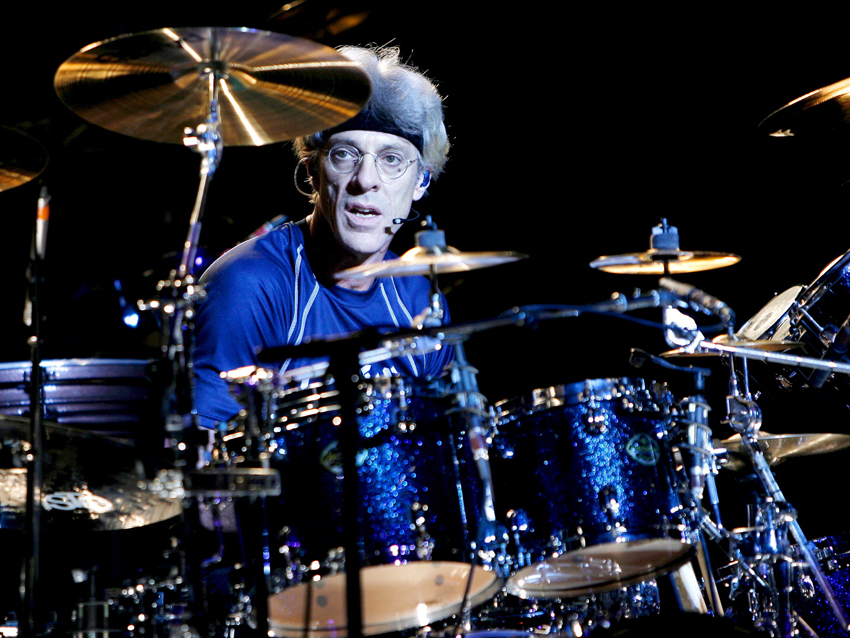

For Stewart Copeland, playing "outside your instrument" is what makes music really sing. © Peter Foley/epa/Corbis

Over the course of his storied career, Stewart Copeland has tangled and tussled with band members, music execs, drum sets, film directors, polo players, and just about anybody and everything necessary for the advancement of his myriad passions and pursuits.

And the day that we speak with the legendary drummer and composer, he's engaged in another battle, albeit a more personal one: "I'm getting over a flu," he says, which is surprising because he sounds both chipper and robust. "I'm not so bad now, but my head is still full of phlegm. Hopefully, I won't make too many coughing and retching sounds."

Timing to a drummer is, of course, everything, and if one simply must get the flu, Copeland found just the right pocket: He recently wrapped a residency at Southern Methodist University's Meadows School of the Arts in Dallas, and in early July he heads to London for the UK premiere of his three-movement composition Gameien D'Drum. After that, he'll hook up with his onetime Animal Logic bandmate Stanley Clarke for a European tour.

With a resume and history as full as Copeland's, there's much to talk about. "If the subject is me, I'll be endlessly fascinated by our conversation," he jokes, and indeed, during our lengthy chat, one which covers topics such as his time in The Police, how he approached his drum solo on the David Letterman show last year (and what he thinks of solos in general), his friendship with Neil Peart (whose band, Rush, he doesn't listen to), double bass drum pedals, the concept of "playing outside the instrument," and why keeping a simple beat offers infinite possibilities, Copeland proves to be a gripping raconteur.

And this is just Part 1. Keep your eyes peeled for the conclusion of our interview with Stewart Copeland.

Last year, your good friend Neil Peart told us about a term you came up with, the 'Eric Clapton Factor,' stemming from the fact that Clapton hated not being able to go out and play the guitar casually - he felt the pressure to be brilliant all the time. Neil said you stopped playing the drums for a while for the very same reason.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Well, it wasn't so much that. For about 10 years, I was a film composer, and I was quite consumed with that. Bashing on the drums just receded into the distance. But then, during those times when I was called upon to play something, and the chops had vanished - they were long gone - I felt a responsibility to be Eric Clapton, as in 'Eric Clapton is God,' and I didn't feel like I could deliver, and so I became very reluctant to play drums in public. Until Les Claypool called and said that it was my civic duty."

Which was the start of Oysterhead.

"Yeah. That's right."

And Oysterhead, like The Police, is a trio. What do you find so fascinating about the three-piece approach?

"It leaves a lot of room to do stuff. In fact, the trio is a good format for making a band. But actually, playing with 10 guys on stage, or 50 or 90 guys on stage, is just as much fun and can be even more fun. The trio thing is really about forming a band and having a unit, and when you have a creative collaboration, the fewer cooks the better. Just make sure they're the right cooks." [laughs]

But whatever the number of people - or cooks - it's still a matter of finding ways to fill the space.

"That's what I've been saying for years. But I have discovered that when you play with lots of guys and they're filling up the spaces, it allows you to be more economical in your own contribution. Collaboration is what it's all about. The joy of playing music is the joy of collaborating. For instance, if there are a lot of percussionists on stage, it gladdens my heart - all those 16th notes that some other guy is playing are things that I don't have to play, and I can look for other places to put the pocket."

Last year, you participated in Solos Week on the Late Show With David Letterman, as did Neil Peart. We talked with him right as he was preparing for his segment -

"Did he give you his sorry tale?"

A sorry tale? Well, he was trying to shorten the live solo he had been playing on tour to fit the time constraints for TV. In fact, he was doing some serious math…

"See, I was having the exact opposite problem: I was trying to figure out how to drag out my three chops to last long enough to be called a drum solo, as opposed to a drum break. I don't do drum solos. In fact, I've only done two in my life: one time was on Letterman, and the other was in Africa when I was performing for lions. [In a scene in his 1985 film The Rhythmatist, Copeland plays drums in a steel cage while surrounded by savage, hungry beasts.] That second time, hitting the drums as loudly as possible was the only thing that saved my skin."

So the Letterman crowd was a better audience?

"Than the lions? Yes, they were much more appreciative. The lions were a very cold audience. They ran away - which was pretty much the desired result."

It's interesting that you did the solo on Letterman; Neil said you were very "anti-drum solo."

"Mmm… not so much. I pull Neil's chain on this at every possible opportunity, of course. You know, when I was a kid, I dreamed of playing a 17-hour drum solo. Then I grew up."

Because you had to stretch the solo you played on TV, did that mean it was more improvised?

"It was composed. I figured out 'First, I'll do this bit here, then I'll go to that and do that little bit here, and then I'll go over here and do that.' And I remembered that the last time I'd composed a drum solo was in college, which entailed me stringing together my coolest chops.

"Then, as I say, I grew up and became a professional musician. Years went by, decades went by, and I was called upon to actually do a drum solo in front of an audience. It was pretty much the same process, and it took me back to that water tower on the grounds of the college."

By the way, just curious: What did you think when Rush added some Police-type elements to their music in the early '80s?

"I had only heard of it. I didn't actually listen to Rush albums, and I couldn't tell you one from the other - although Neil is a good buddy. [laughs] We agreed to disagree on certain things, and it is a measure of his greatness as a human being that he is completely over whatever my feelings might be about Rush.

"This truly is the case: He's never heard me say a wonderful thing about his band. He's read a few comments that I wish he hadn't read. In unguarded moments, things tend to slip out. Musicians tend to be snippy about one another, and I'm generally not. I generally love all music and all players.

"There was a time when bands like Rush were the epitome of what The Police were theoretically against, which was an overemphasis on musicality. Our ethos in the early days was about the primal scream and that musical technique was a distraction from that mission. There may have been a few comments that I might have made regarding Rush's position on that debate, and it is really, really to Neil's credit that he's over that debate. And we get along great."

Yet, at the same time, it's no secret that The Police packed a lot of musical sophistication into some pretty tight songs.

"Yeah, but that was by accident."

Some years back at a drum clinic, you startled the crowd when you played nothing but a simple beat for two minutes straight. Do you feel that drummers still miss the point you were trying to put across?

"The point was that there is so much expression in the execution of a mantra-like rhythm, that when you strip it right down, the tiniest things, the most minute fluctuations of the 16th note hi-hat, have great effect. And you don't get that effect unless everything else is extremely streamlined. The point I was trying to make is that within the confines of a very strict, repetitive loop, you can really have a world of expression."

You proved as much with Every Breath You Take. For the most part, you keep the beat simple and steady, but you throw in crashes out of the blue. So many drummers can't get those moves down.

"Nor can I. I think at the last Police show, we were still arguing how to get from the chorus back into the verse."

Are you considered a lefty? You write with your left hand…

"I'm left-handed, but I play instruments right-handed. It's just more convenient that way. And because most instruments require both hands to be working real hand, I find that you have to be ambidextrous. Like most left-handed people, I am close to being fully ambidextrous."

So on the drums, you're kind of a Ringo.

"I guess. I wasn't aware that he's left-handed."

He's a lefty and plays with his kit set up for a righty.

"But see, it's a right-handed world, and for lefties, our right hand is better than the left hand on righties."

Ringo would always say that the reason his playing was so unique was that, unlike other drummers, he played with his kit set for a righty, but he would still lead with his left.

"Mmm… I think that's an interesting thing for him to say, but I don't know if it's true. He leads from his heart, which is what makes him such a good drummer. Which hand does what follows where in his solar plexus he feels the rhythm is. All hands and feet are on the same mission.

"Certainly, sometimes you lead with the left and sometimes you lead with the right, depending on what you're doing - and also which hand is more tired at any particular moment. When practicing, which is different from playing shows or playing music, you work on making both hands just as strong."

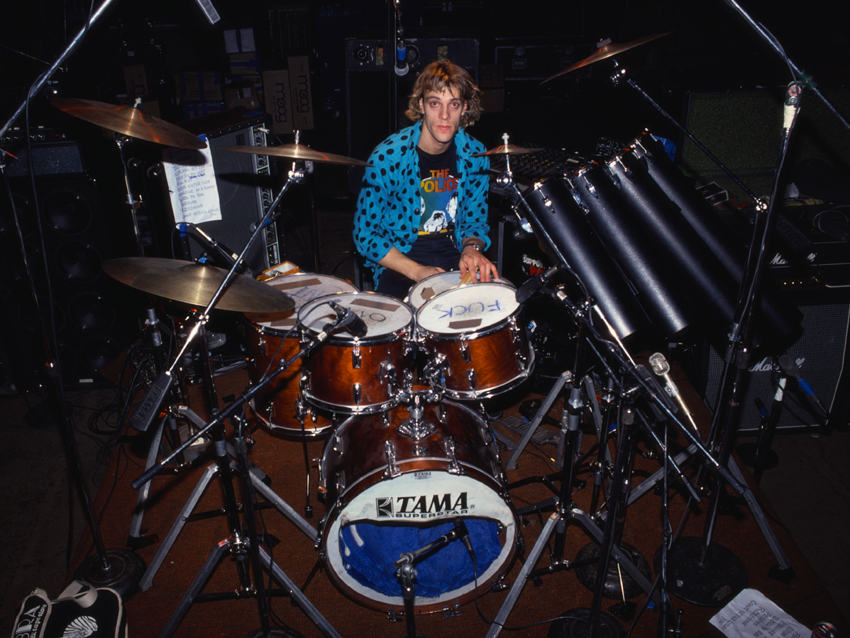

Performing at the La Mar de Musicas Festival, Spain, 2011. © JOSE ALBALALEJO/epa/Corbis

You once talked about "playing outside your instrument." When did you come up with this idea, and can you speak about what it means to you?

"It came to me when I was playing polo - you 'play outside your horse.' If you're thinking about your horse and your equestrian skills, and things like proper riding and hitting the ball, let alone playing the game and putting your horse in the right place on the field…

"See, you shouldn't even be thinking about the horse. You have to be outside the horse. Your body and horse are one. You shouldn't be thinking about riding. You have to think, 'Here's the ball. I need to get it there. I need to stop that guy from getting to the ball. Uh-oh, there's a pass and that's where I gotta be.' When you do that, you're thinking outside your horse. You're playing the game.

"Put this to music: The mechanics of playing an instrument should be furthest from your mind. You've got to think outside your instrument, play outside your instrument. You've got to think about the music: 'What is the music? Where are the other players are? What's going on? Where's the groove?' - things like that. What drum you're hitting, what your technique is - that should be completely subliminal."

When you sat down at the kit with this concept in your head, did you feel as though you played differently?

"I had always thought that way. It was only when I came up with the polo analogy that it crystallized into something that I could make into a riff when talking to people such as yourself."

A while back, you started using a double bass drum pedals.

"Yes! That little bastard in Slipknot…"

Although you seem to have gotten by just fine with a single pedal. Did you ever think of going all-out rock and playing a double bass drum kit?

"Well, I did in Curved Air, much to own personal and musical ruination. [laughs] I don't know why - maybe it was maturity as a musician or something like that - but later on, after seeing what Joey Jordison can do without losing that throb… and they also invented the double bass drum pedal using only one bass drum, which meant that the ergonomics were extremely improved… I don't know, it worked out better when I came back to that.

"I don't use the double bass pedal a lot - just for the occasional flash and effect - but there is one particular thing that it can do; it works like a paradiddle: If you've landed on your foot but you need to get back up to your snare drum, but you need two beats to get your there, you can do go, 'ba-da-bahh!' It's ergonomics.

"Now, John Bonham would have just done that with one foot because he was John Bonham. Because he was... the mountain."

Copeland (seen here in 1980) is Tama Drums' first and longest-term artist endorser. © Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis

Let's talk about The Police a bit. In the early days of the band, you had to make records fast and, one would assume, cheap. Did that youthful hunger, and the limitations you worked with, lead to a certain creativity that was different from when you had lots of time and money in the studio?

"There was certainly hunger, and the hunger was the driving force behind getting up in the morning, figuring out a studio, making that call, calling the other studio and seeing if you can haggle the price down - the mechanics of getting a band going and working and just being were driven by hunger and fear. Once we had slain those dragons and had gotten into the sacred grove of a studio, then it was all the opposite; it was joy, it was creativity, it was the reward, it was the upside.

"However, if our hunger had gotten into the sacred grove, then we would have been more commercial. Basically, we were trying to do something that was really cool. Once our rent was paid, we weren't thinking that we had to make money. In the Police room, we were doing what we thought was the coolest thing that we could do. We weren't thinking about the marketplace at all.

"Back to the hunger thing, yes, outside the band room, I was thinking, This is what we've got to do. We've got to wear this uniform. We've got to fly this flag. We have to spout this ethos to get us into a niche in the music market called punk. You know, we can get in there, we'll cut our hair, and we're jussssst about young enough to squeeze into that demographic. All that calculation - certainly. But in the band room, we just did what we thought was cool."

Andy Summers' embrace of guitar pedal effects predated The Edge by a couple of years. As a drummer, how did you work with the different spaces and sounds he created?

"He created such an orchestral effect that I just wanted to listen to it. Shut me up. What Sting played on the bass pumped me up and made me want to blaze away; it got me all excited. But then I'd hear Andy play one big fat chord that would ring out with those sounds he had... and I was just listening."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.