BLOG: Why sampling isn't stealing

Musicians should be free to rework existing material

I´ll wager that not many Kanye West fans will be familiar with the late jazz saxophonist Joe Farrell, but unbeknown to them, they´ve probably heard some of his music. It transpires that West sampled Farrell´s recording of Upon This Rock for use in his song Gone, but what he didn´t do was get permission to do so.

As a result, Farrell´s daughter, Kathleen Firrantello is now seeking damages from West. Common, Method Man and Redman are also facing legal action, as they´ve accused of sampling Upon This Rock without obtaining clearance, too.

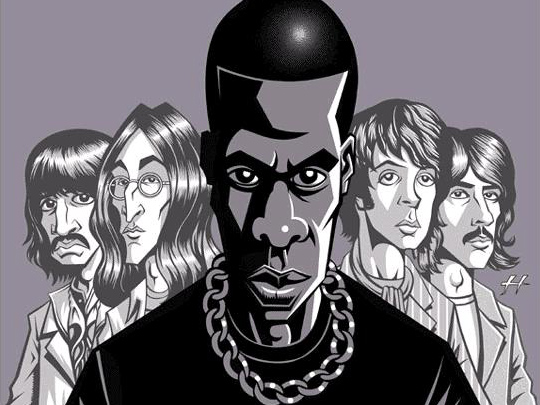

We´ve been here many times before. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were eventually given songwriting credits on the Verve´s Bitter Sweet Symphony when it emerged that the song featured a sample from an orchestral version of The Rolling Stones´ 1965 cut The Last Time, and EMI tried to block the release of Danger Mouse´s The Grey Album, which used significant chunks of The Beatles self-titled 1968 LP (or The White Album, as it´s commonly known).

The process of sampling another artist´s work for use in your own is now so simple and commonplace, though, that I think we have to ask whether the time has come for the law to be amended.

It´s certainly true that the intellectual property rights of artists need to be respected, but if someone takes a sample and uses it in an innovative, creative way - and one that won´t compromise the commercial viability of the original song - should they really be forced to share the credit and any resulting royalties? In most cases, the original artist actually benefits when their track is sampled, as fresh attention is drawn to them and their work.

I´m not advocating a situation where anyone is free to sample anything - if a song´s main hook comes from another track, the original artist should be acknowledged and compensated - but let´s face it, rock musicians have been recycling each others´ riffs for years, and not many of them end up in court (not on copyright infringement charges, anyway).

In 2005, the then UK Chancellor Gordon Brown commissioned the Gowers Review of Intellectual Property. The subsequent report was published late in 2006; you may remember that most of the media attention focused on the recommendation that the copyright of recorded material should not be extended from 50 to 95 years. However, elsewhere in the report, Gowers also suggested that UK copyright laws “be amended to allow for creative, transformative or derivative works”.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

If such an exception were ever to be made (and it should be stressed that, at the time of writing, there´s no suggestion that it will be), musicians who used samples as the basis for new, ‘transformative´ works would be able to do so without getting the permission of the original artists/composers (providing they weren´t deemed to be producing work that would be against the original creators´ commercial interests).

Policing such an exception could be problematic - who would judge whether or not a new song was transformative enough, for example? - but I think its implementation would certainly be a step in the right direction. Music has changed, and the law needs to change with it.

By Ben Rogerson

I’m the Deputy Editor of MusicRadar, having worked on the site since its launch in 2007. I previously spent eight years working on our sister magazine, Computer Music. I’ve been playing the piano, gigging in bands and failing to finish tracks at home for more than 30 years, 24 of which I’ve also spent writing about music and the ever-changing technology used to make it.