"There are certain laws that must be followed, whether you like it or not": Here's what producers really need to know about music theory

Get a grip on the notes in your piano roll and start creating more meaningful music

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Music theory is a hot topic of debate amongst modern producers because it’s arguably not as integral to music production as it once was.

However, it definitely still holds a rightful place and can only add improvements and efficiency to any musician’s workflow, should they take the time to learn it. For example, investing time into understanding how musical scales function and why each note in a scale works in relation to one another can better equip you to compose effective melodies and chord progressions.

There are parts of music theory that might seem completely insignificant to most present-day virtuosos, like being able to write and read sheet music, but there are certain laws of the theory that must be followed if you want to write any kind of harmonious music, whether you like it or not. Even those who pride themselves on expressing how entirely unnecessary music theory is understand what a tempo is and will intuitively understand when something is and isn’t in-key.

We previously mentioned musical scales, and this will be the foundational building block of this article’s contents because musical scales are the fundamental piece of music theory that allow us to write and perform music in a sensible manner. In Western music theory, we primarily use what’s called heptatonic scales: scales consisting of seven musical notes at a time. These scales can all be derived from the Western 12-tone-equal-temperament octave system (ie the 12 notes we all know).

You may be familiar with the term ‘octave’. When you look at a Western musical keyboard or piano, you’ll see the same 12-note pattern repeating over the span of the interface – the pattern is noticeable by following the black keys. Note that the black keys go from two equally spaced intervals to three over and over. If you count the amount of white keys in addition to the five black keys in each pattern, you get 12 notes: making a single octave.

Music theory 101: notes, intervals, scales and chords explained

Each musical scale in Western music theory can be derived from these 12 notes and the two most predominant scales are the “diatonic” major and minor scales, which can be formed from any of the keys out of the 12 octave notes. In a scale, the starting note will determine the root note of the scale. The key also determines which seven out of 12 notes will be in-key when forming melodies and chord progressions in that given key/scale.

The major and minor scales are determined by their respective pattern of notes. This pattern dictates which successive notes can be played in that scale. The major scale ‘formula’ is W-W-H-W-W-W-H and the minor is W-H-W-W-H-W-W, with each W representing a whole interval and each H representing a half interval. Each successive key on a keyboard is a semitone (half) difference in pitch, so when you need to move a whole interval, you skip a key.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Building basic scales and triads

Let’s use the C Major key. Starting on the root note (C) and following the major formula, note that no black keys appear. This makes C Major the easiest scale to learn. In ascending order, play each white key from C to C, left to right in any octave.

You can now make an in-key melody in C Major by using any of these same keys in sequence. You can also place notes of the same keys in higher or lower octaves. Know a tune in C major? These notes should sound good when played along with it.

Now, let’s build a chord. We can build a basic triad chord by playing the first, third and fifth note in the scale at once. In this case, C, E, and G. This interval pattern of using the first, third and fifth note forms a triad chord out of any scale.

Now for C Minor. Using the minor formula of W-H-W-W-H-W-W, starting from C, you’ll have three sharp (black) keys to use (C D Eb F G Ab Bb C). You can now make a triad chord in C Minor by playing the first, third and fifth notes in the scale.

The minor scale sounds melancholic next to the major scale. Every major scale has a relative minor scale made from the same keys. The only difference is the root note. A Minor is the relative minor to C Major.

You can experiment with different scale types by looking them up online. For instance we can play harmonic minor scale by using a slightly different formula and raising the seventh note by one semitone.

Adding extensions to chords

Let’s dive deeper into chords with a look at chord extensions. We can build upon the C Major triad chord in our previous tutorial by adding additional notes from the scale. You can add a seventh to the end of the first, third, fifth formula (C-E-G) to create an extended seventh chord made from four total notes (C-E-G-B).

What happens when we add a ninth to the formula? Can we add a ninth when the scale only consists of seven notes? We can, by reaching into the next octave. If we add a fifth key at the ninth interval to our C Major chord, we add a D, which is technically C Major’s second note. The ‘C Major Ninth’ chord is (C-E-G-B-D).

By borrowing notes from other octaves, we unlock a wide range of combinations to add different flavours to your chords. Add notes from the higher octave, such as the 11th and 13th intervaled notes (F and A) and they’ll still be in-key. Try that now with the C Major chord. You can add both, or the single 11th.

Sometimes too many notes can sound cluttered. You can experiment with removing certain notes from the sequence, like the third in your base triad. Technically these chords are not extended chords because an extension requires all previous intervals included. Try removing your chord’s third (base triad’s middle key), whilst keeping the ninth and eleventh.

Voice leading – keeping chords smooth

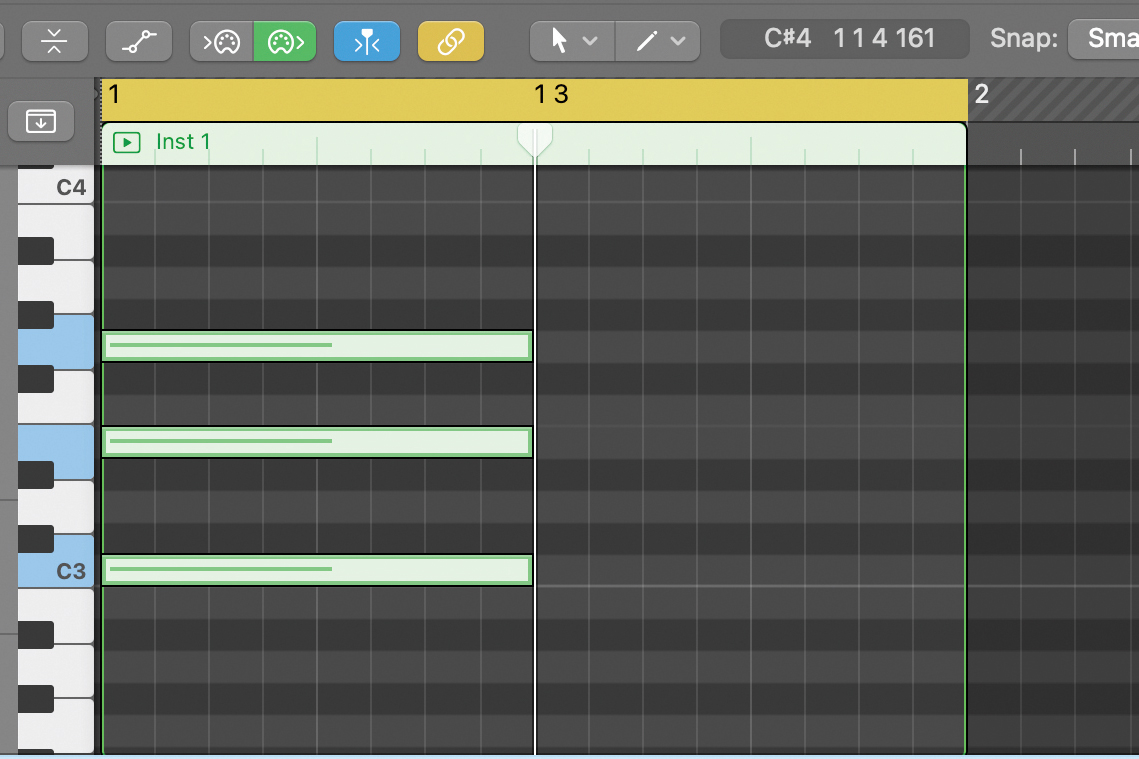

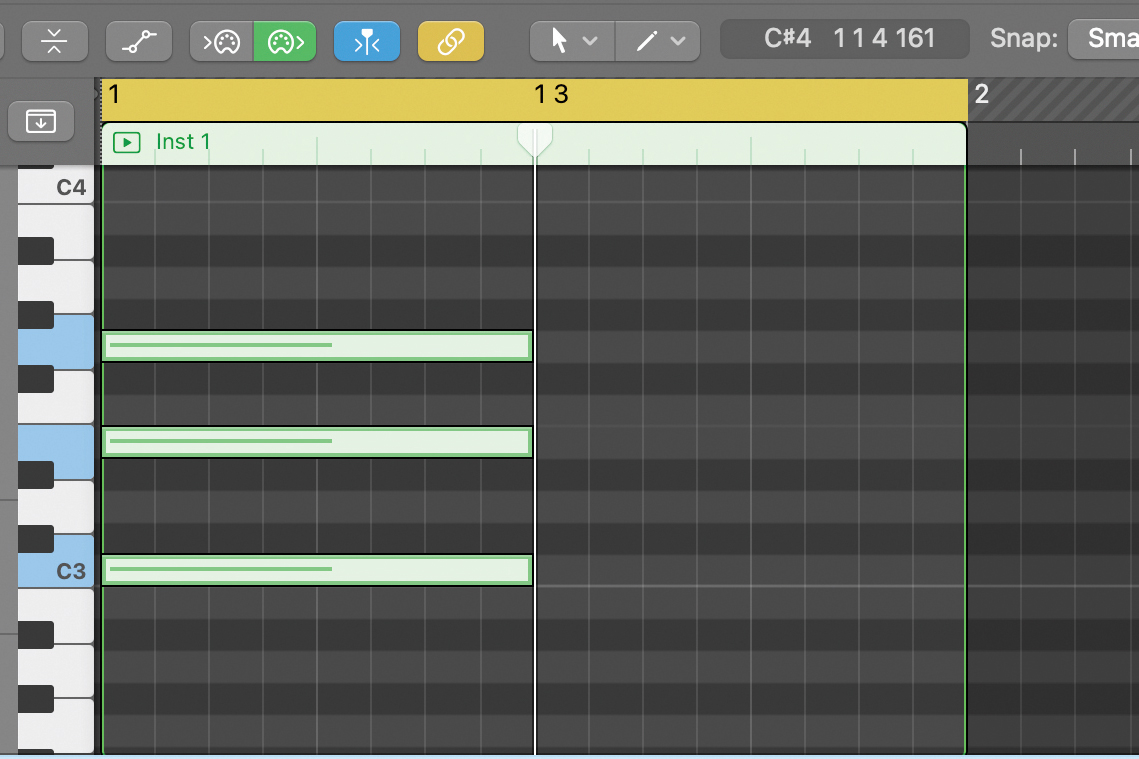

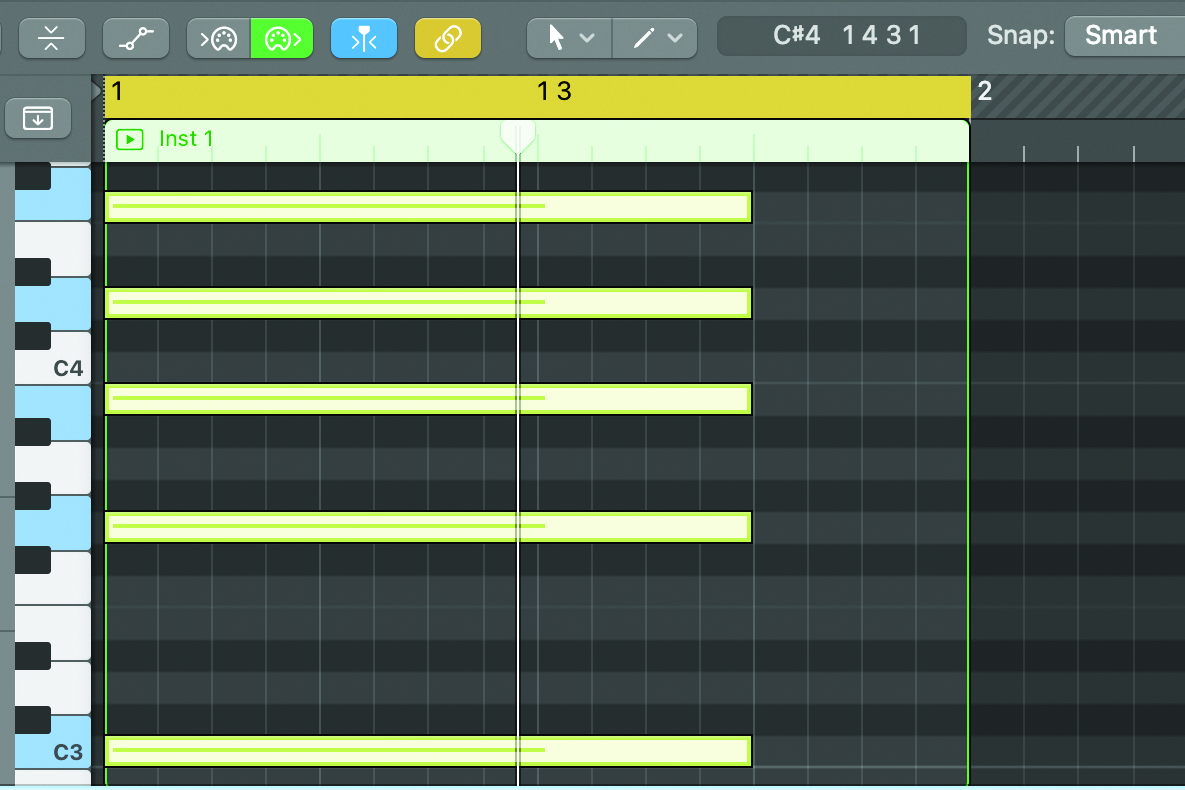

Chord inversions allow us to shift the order of keys from any given chord combination and play it in different ways. For example, an A Minor triad consists of the keys A, C, and E. But you can also play this chord by rearranging the order of the notes. You can play it as C, E, and A, or E, A, and C. Even though the order is different, the chord’s identity remains in place.

With chord inversions, we can keep chords contained in a single octave, which can lead to more complementary chord progressions for our melodies

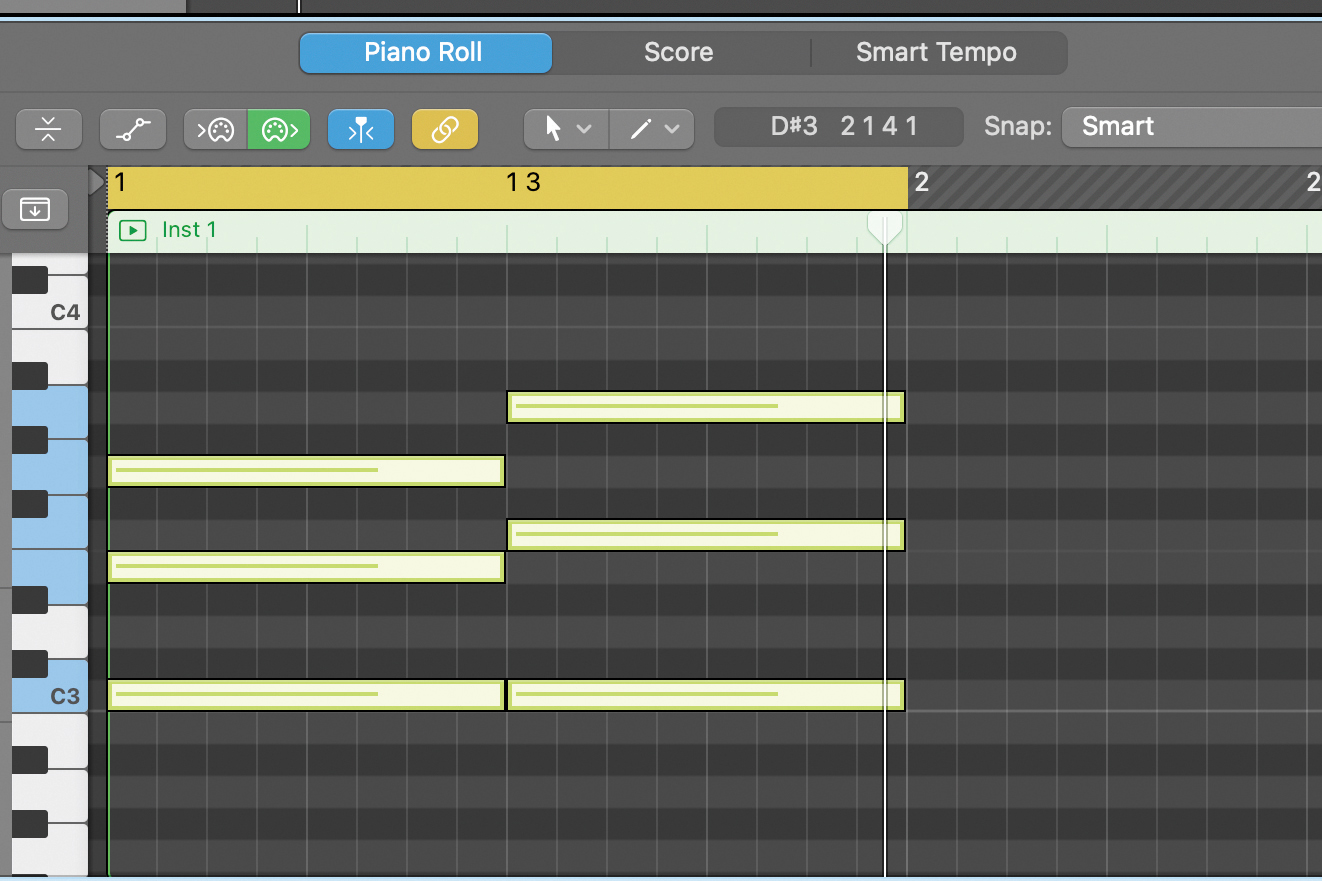

With chord inversions, we can keep chords contained in a single octave, which can lead to more complementary chord progressions for our melodies. If we wanted to play an A Minor triad and keep it in the same octave as a previous chord, we may need to change the note order to make it fit, because if the C is the last note in sequence, it might fall into a higher octave. Chord voicing is when you purposefully take a successive key in a chord and play it in another octave.

Chord inversions and voice leading

Each chord has a number of inversions. This goes for basic triads, as well as extended chords. Let’s use the F Major triad to demonstrate chord inversion. The F Major triad is made from the keys F, A, and C. Try playing it as C, F, and A, or A, C, and F.

Chord inversions are great for keeping chord progressions in one octave. With two triad chords of C Major and F Major in succession, the F naturally breaches the next octave. An inverted F Major triad brings higher notes back into the same octave.

Via chord voicing, we can play different notes from any chord combo outside of the original octave. Let’s add a seventh extension to a basic F Maj triad (the seventh on E), an octave lower. We’ve placed it on the E directly before our root note.

Coming up with basslines and melodies

Now that we have some knowledge of how scales and chords work, we have creative freedom to write some melodies and basslines in any given scale. However, there’s an art to writing melodies and basslines in ways that make them sound musical to the ear and work in harmony with each other.

For instance, you could place a bunch of random in-key notes into your MIDI sequence – but that doesn’t mean that they’re going to automatically sound great. The same thing can be said for writing a bassline. So what is it, in exact terms, that makes for a good melody and bassline?

Good melodies tend to make use of certain repeated notes, as well as diversifying different note lengths per beat and measure

It might all come down to rhythm and groove. When breaking down a good piece of music, you’ll notice patterns in the melodic structure that can give you clues. The same can be said for the bassline. For instance, good melodies tend to make use of certain repeated notes, as well as diversifying different note lengths per beat and measure. There’s a combined element of predictability and unpredictability.

A good bassline groove plays off of the rhythm created by the main melody, and usually doesn’t have as much diversity. You can think of it as the foundation of the composition. When learning to play musical pieces on piano, you’ll find that, usually, the left hand (in charge of playing the lower octaves – bass) has much less moving around to do than the right hand (controlling the higher notes and main melody). You’ll also have perhaps noticed that the bassline often follows the starting note on each beat of the melody.

Coming up with basslines and melodies

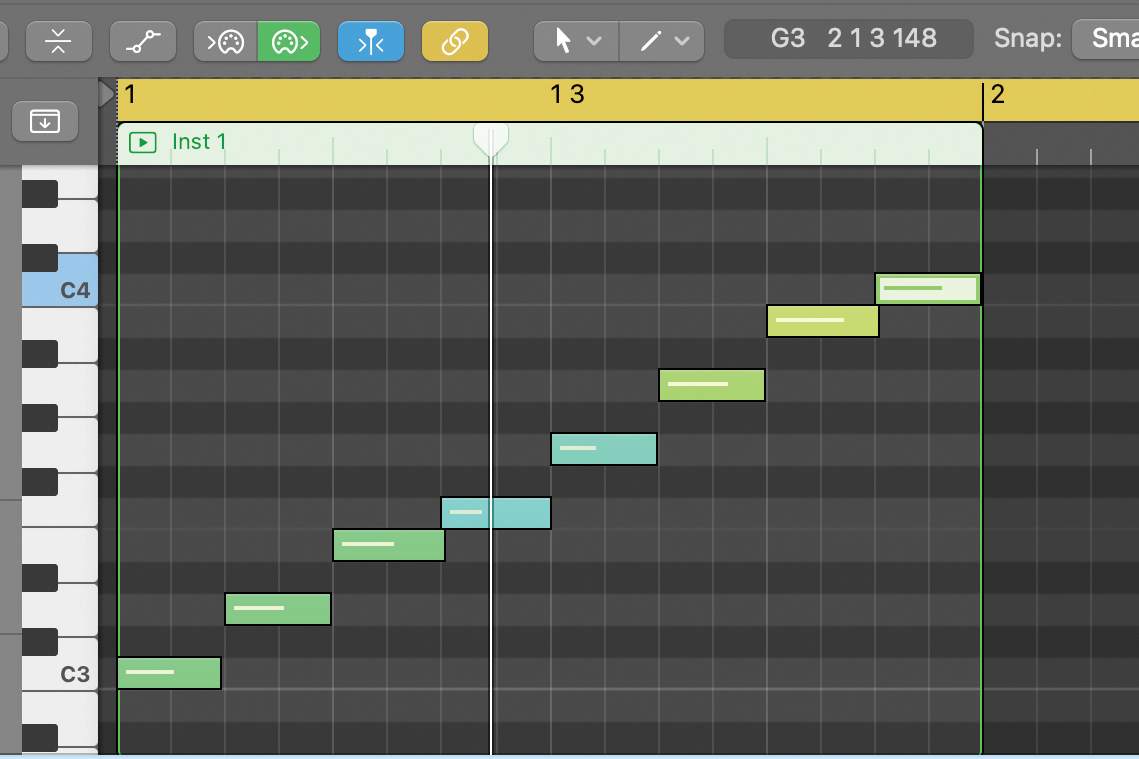

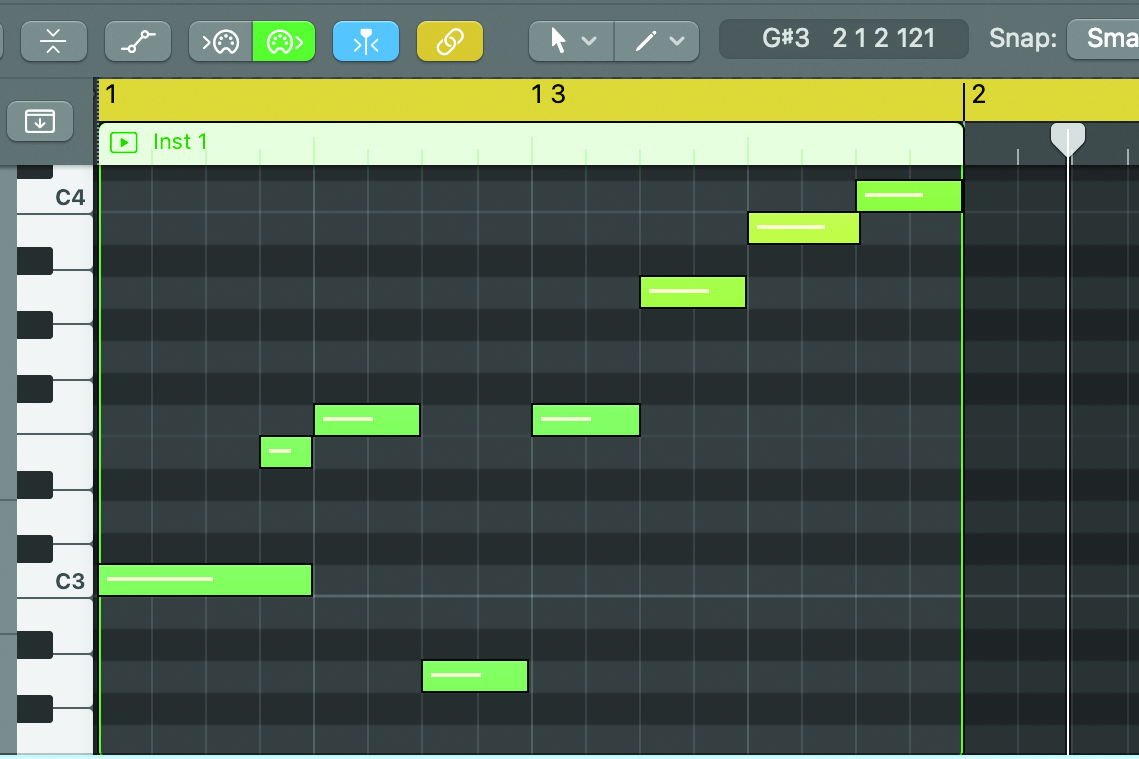

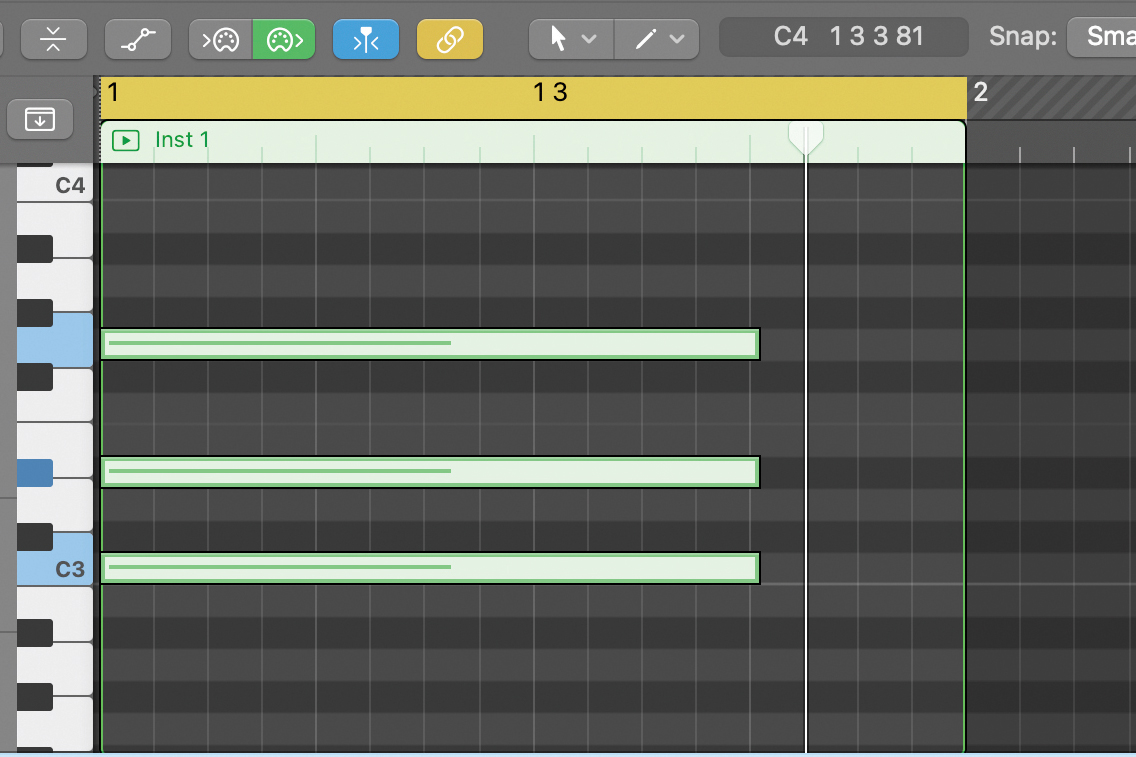

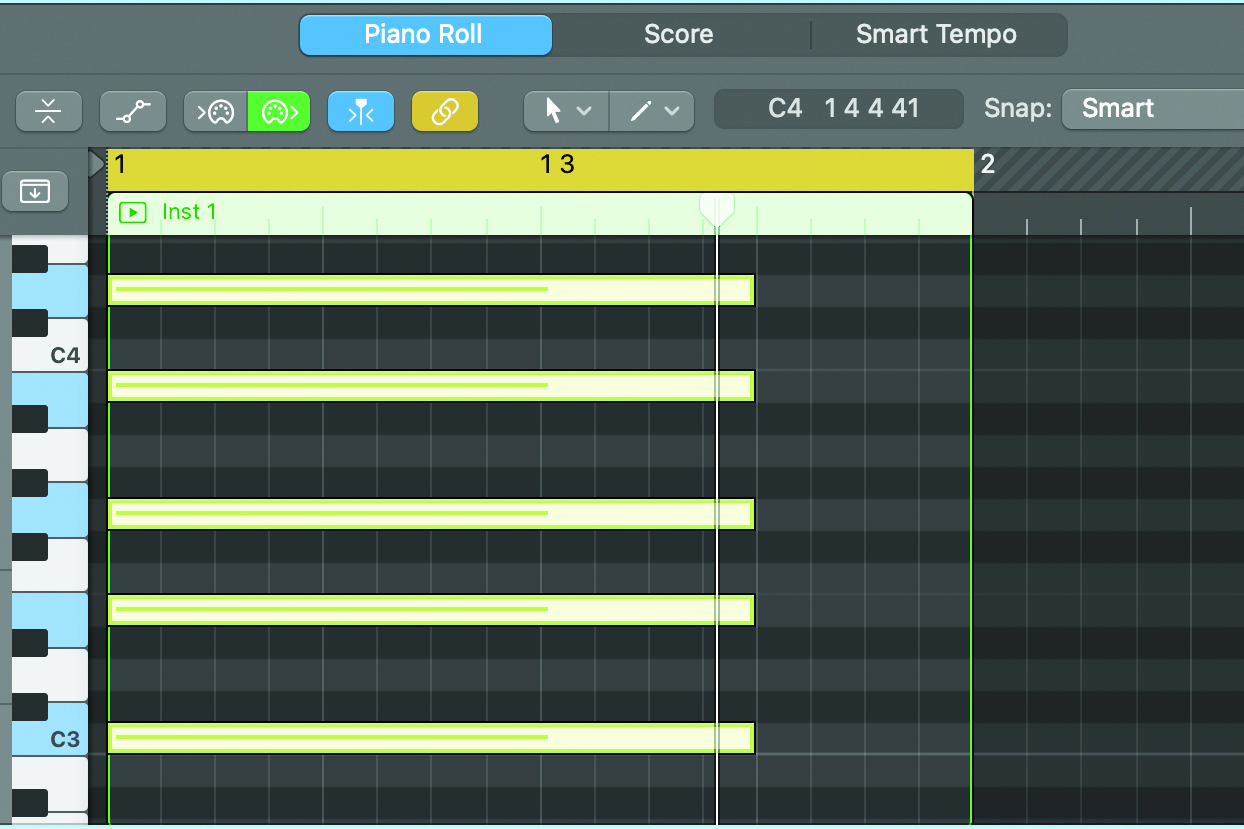

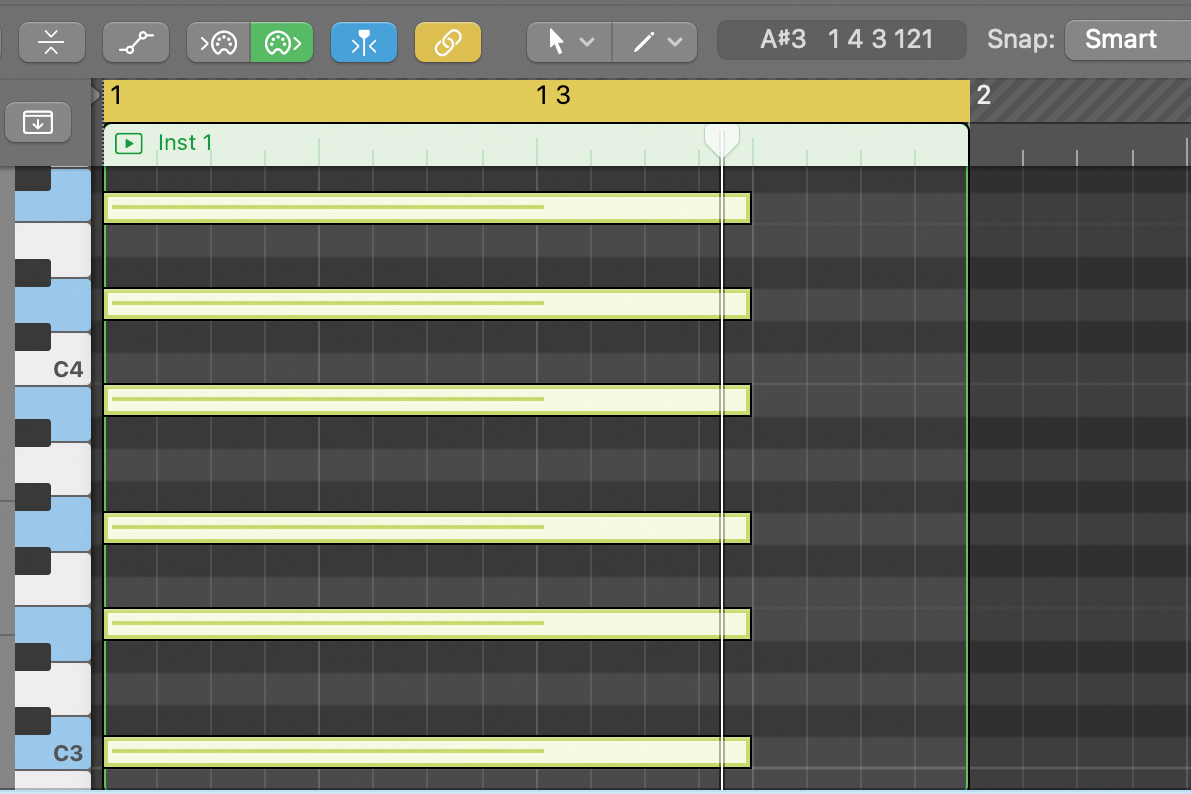

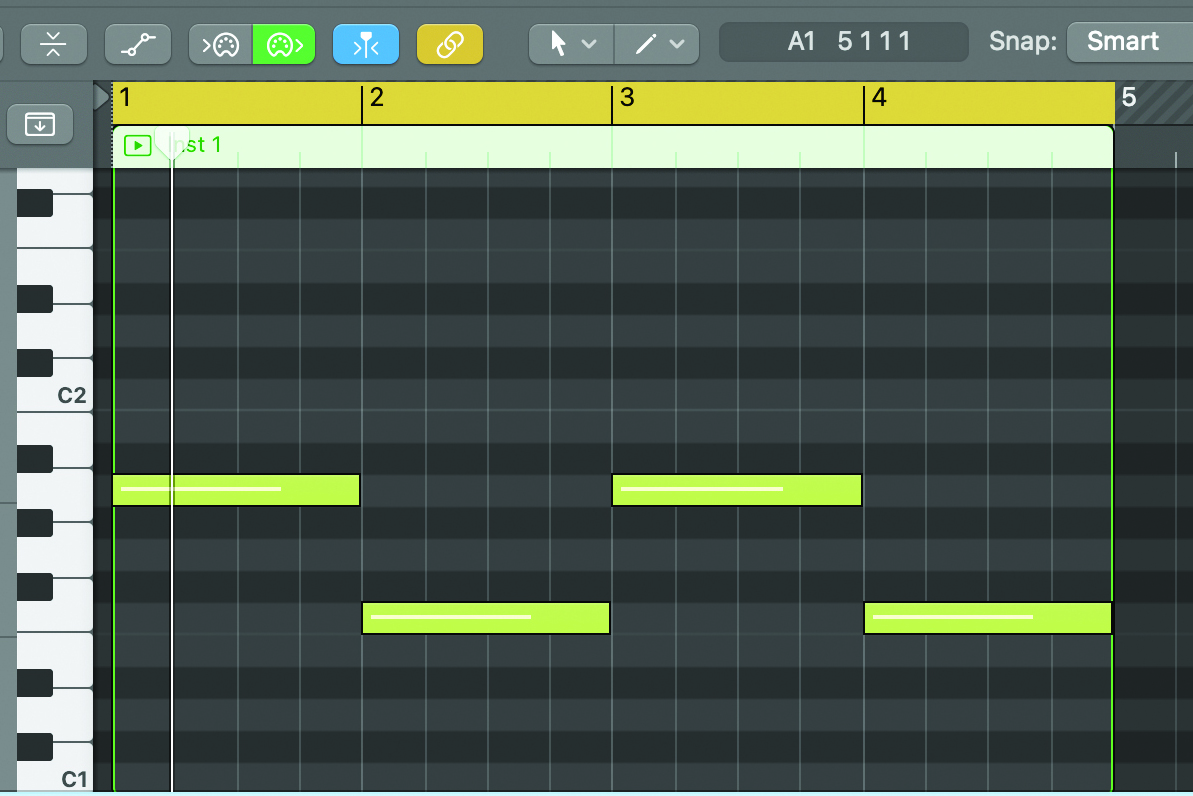

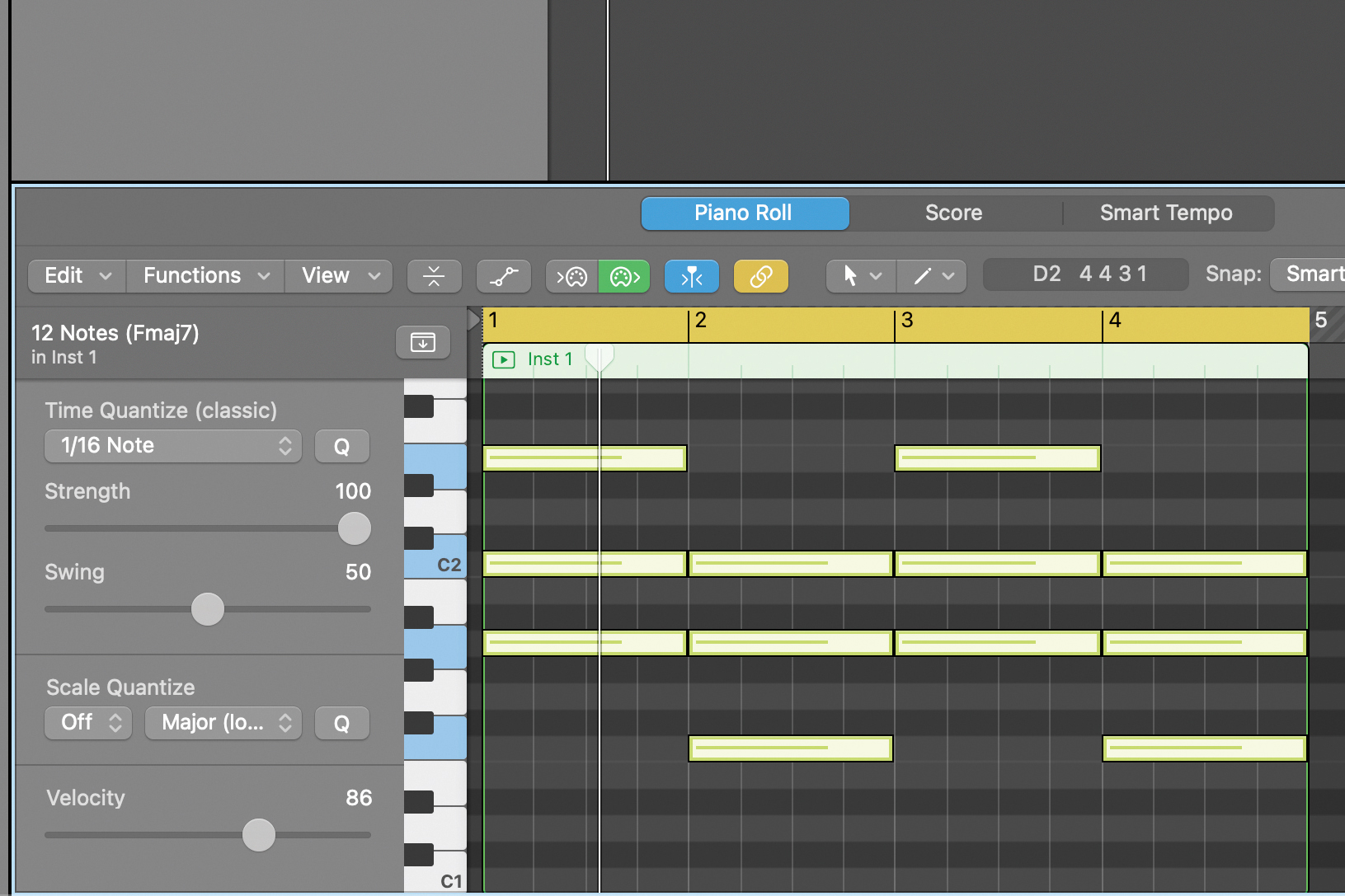

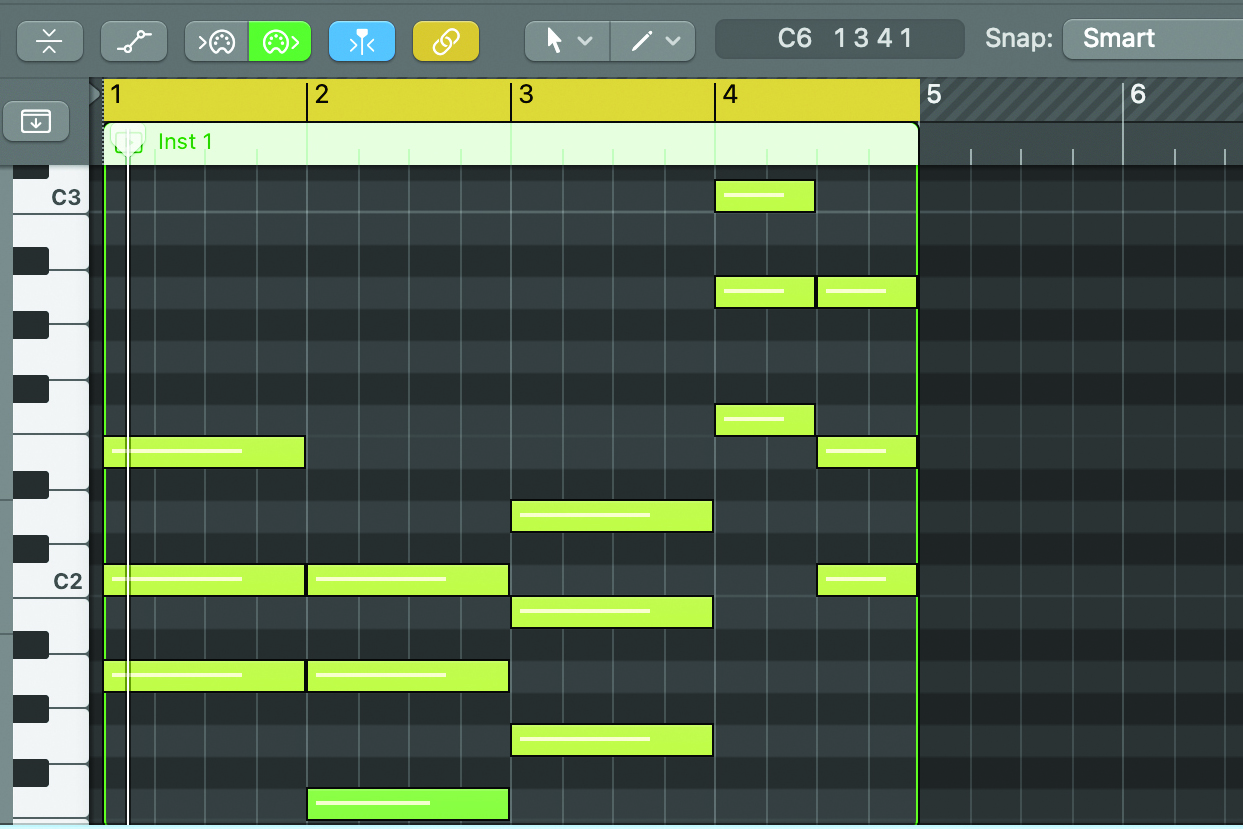

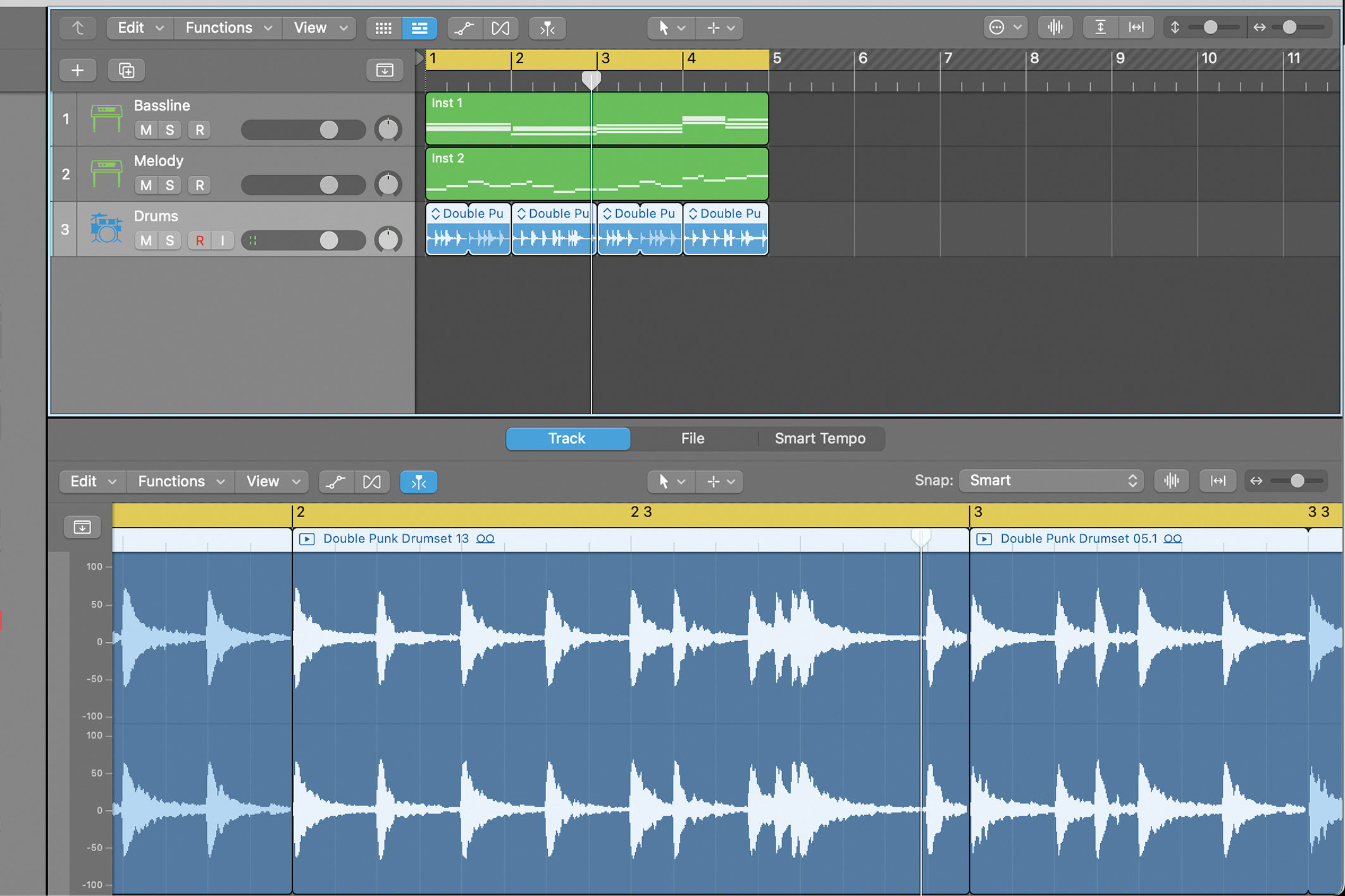

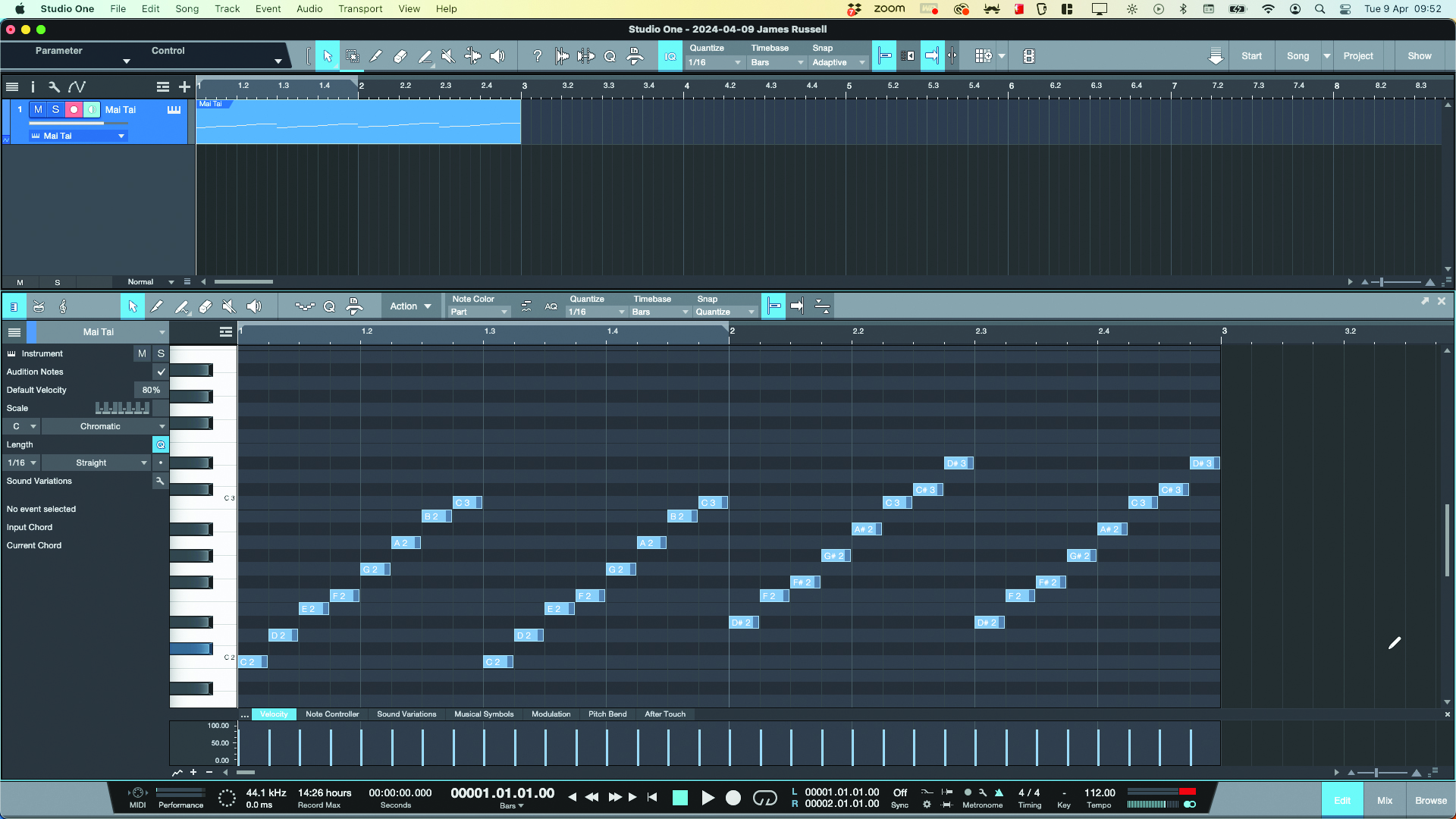

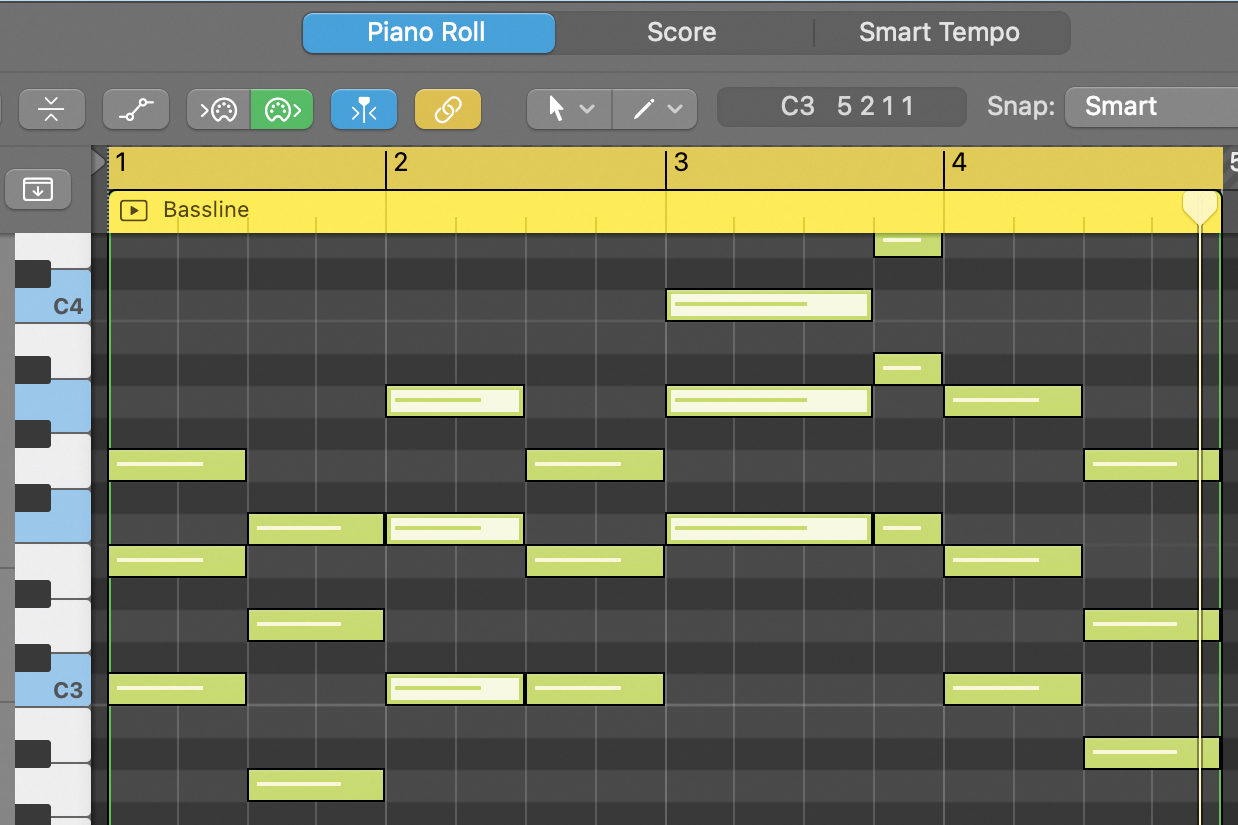

Let’s compose a quick musical loop in A Minor, starting with the bassline. Set your DAW to play for four bars length. Then using your Piano Roll, lay a simple bassline going back and forth from A to F on each bar (a full measure of four beats).

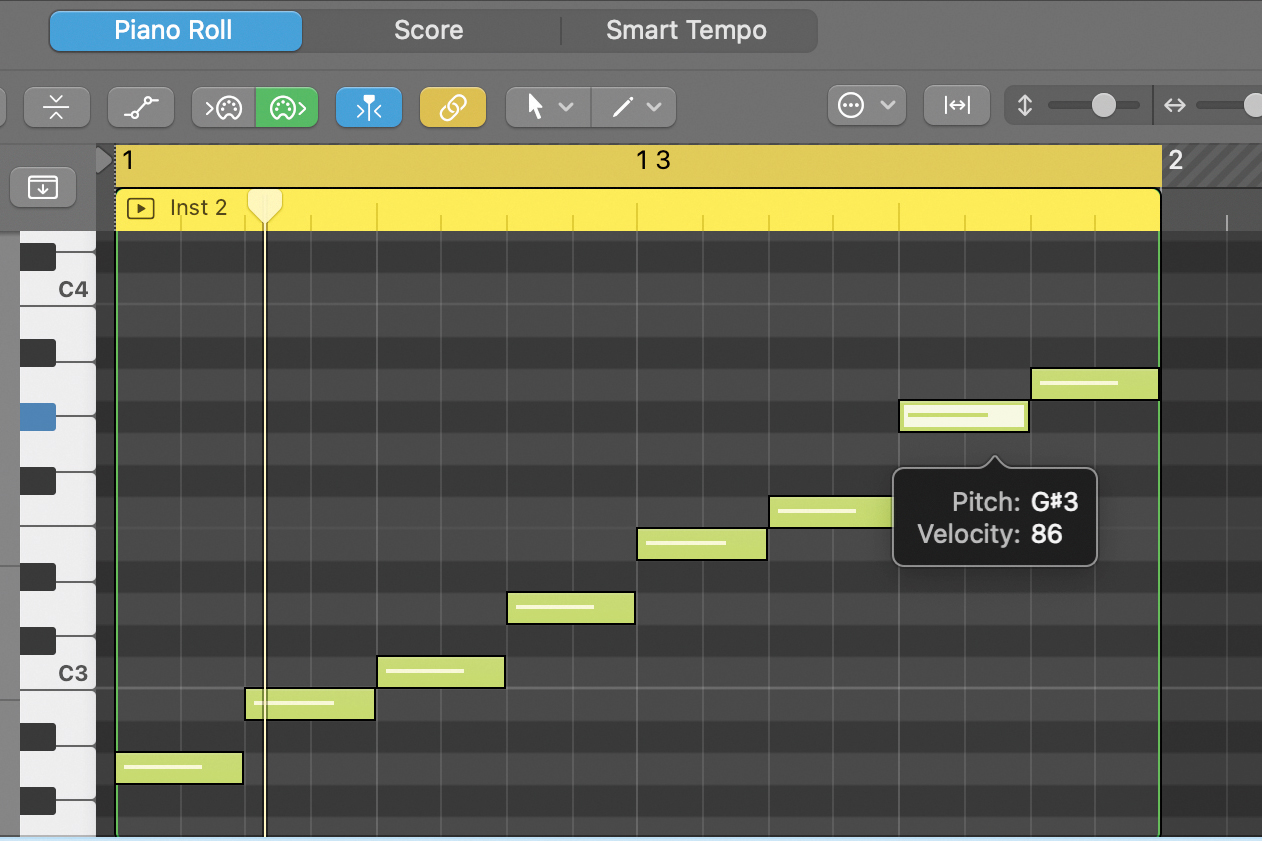

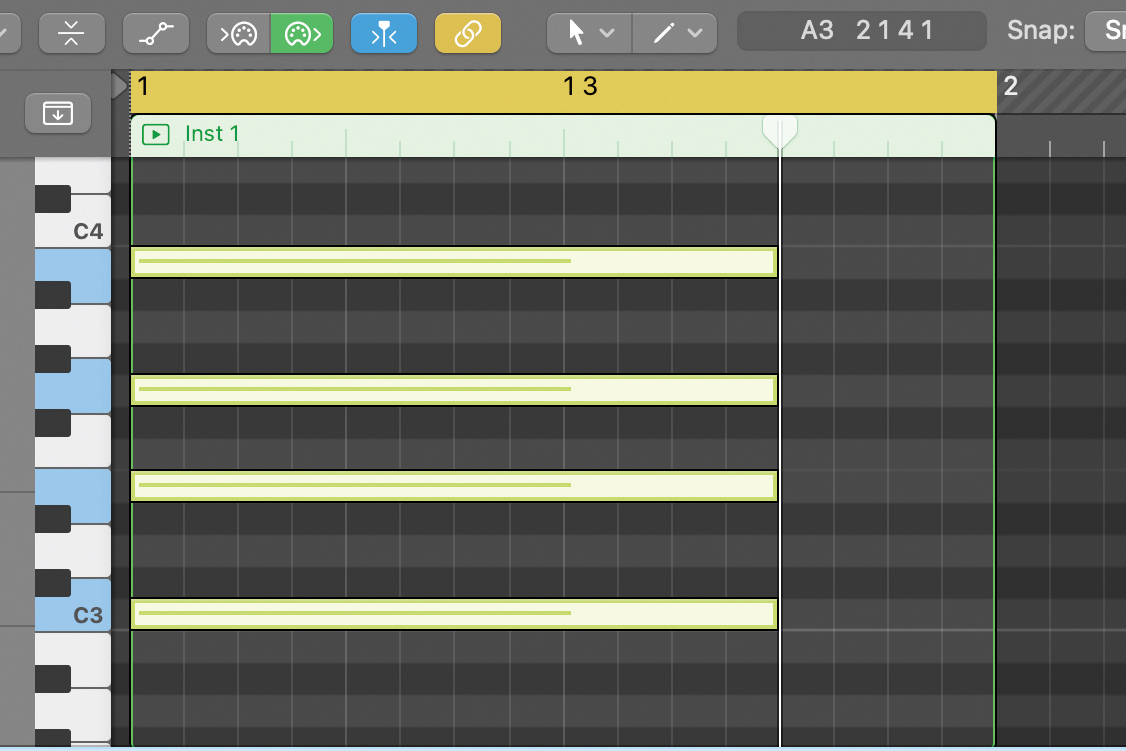

This sounds pretty basic, but using our knowledge of chords, we can turn our bassline into a chord progression to spice it up. Try adding the third and fifth notes to turn each bar length into a triad chord. A groove is starting to form.

The progression is still quite basic. Let’s try switching the third chord to a G Major to add variety. You could also change your final chord, and split it into two. Perhaps throw in a chord inversion. What we’ve learned will build variety.

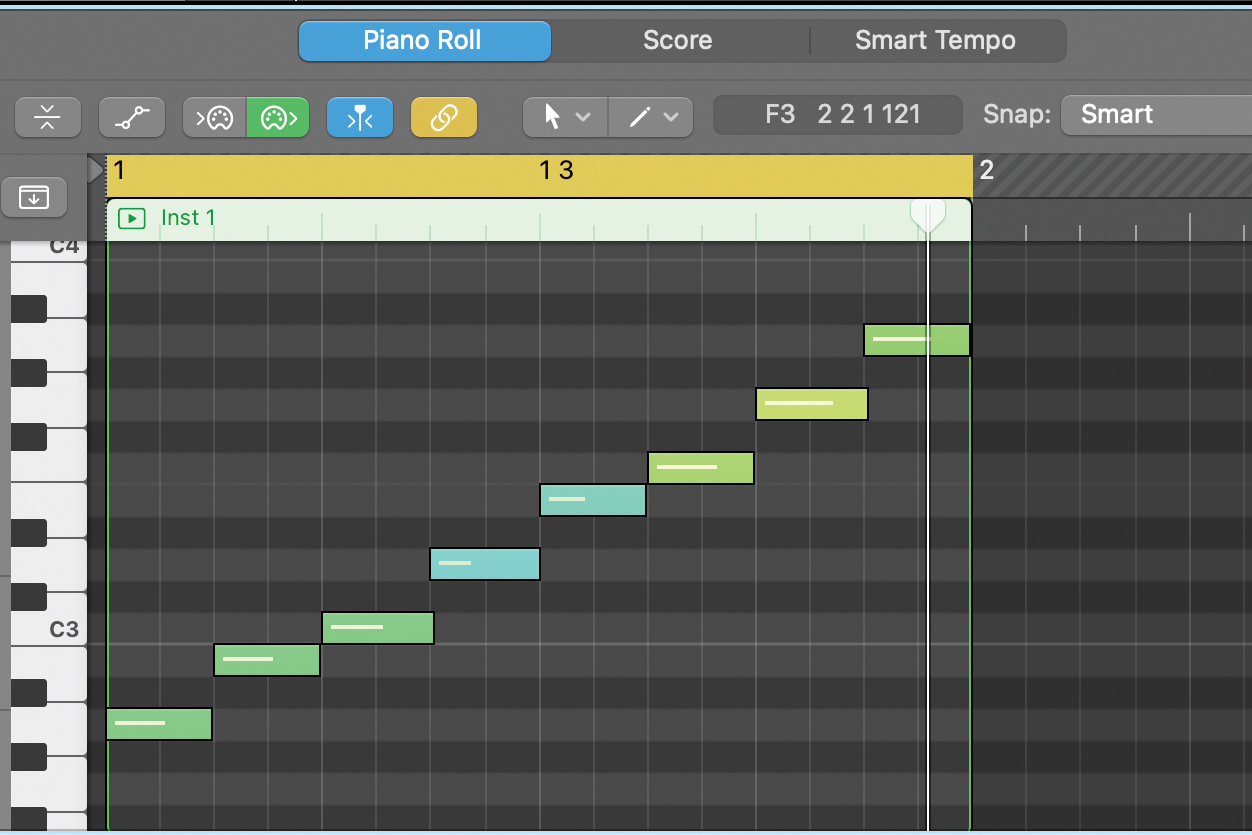

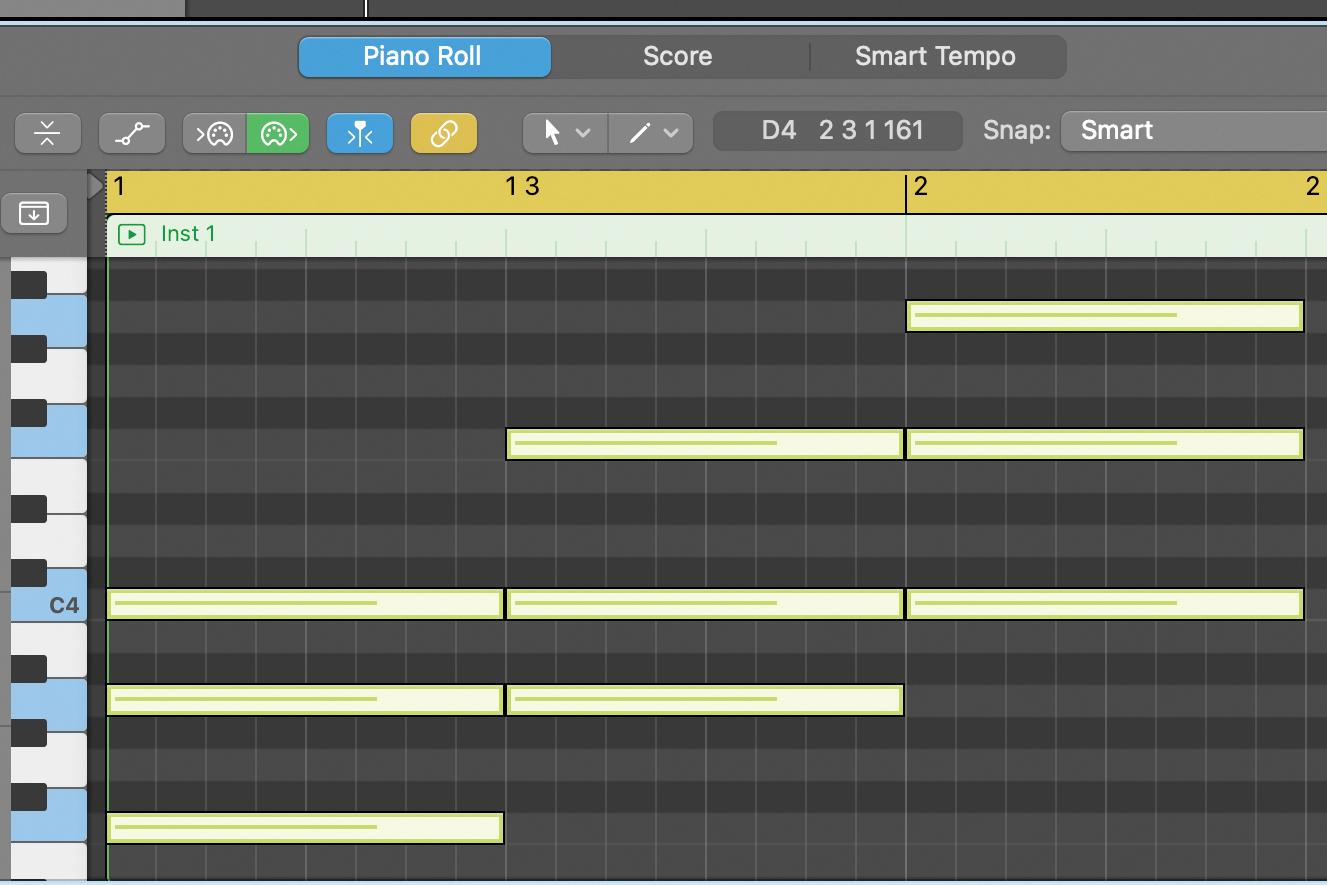

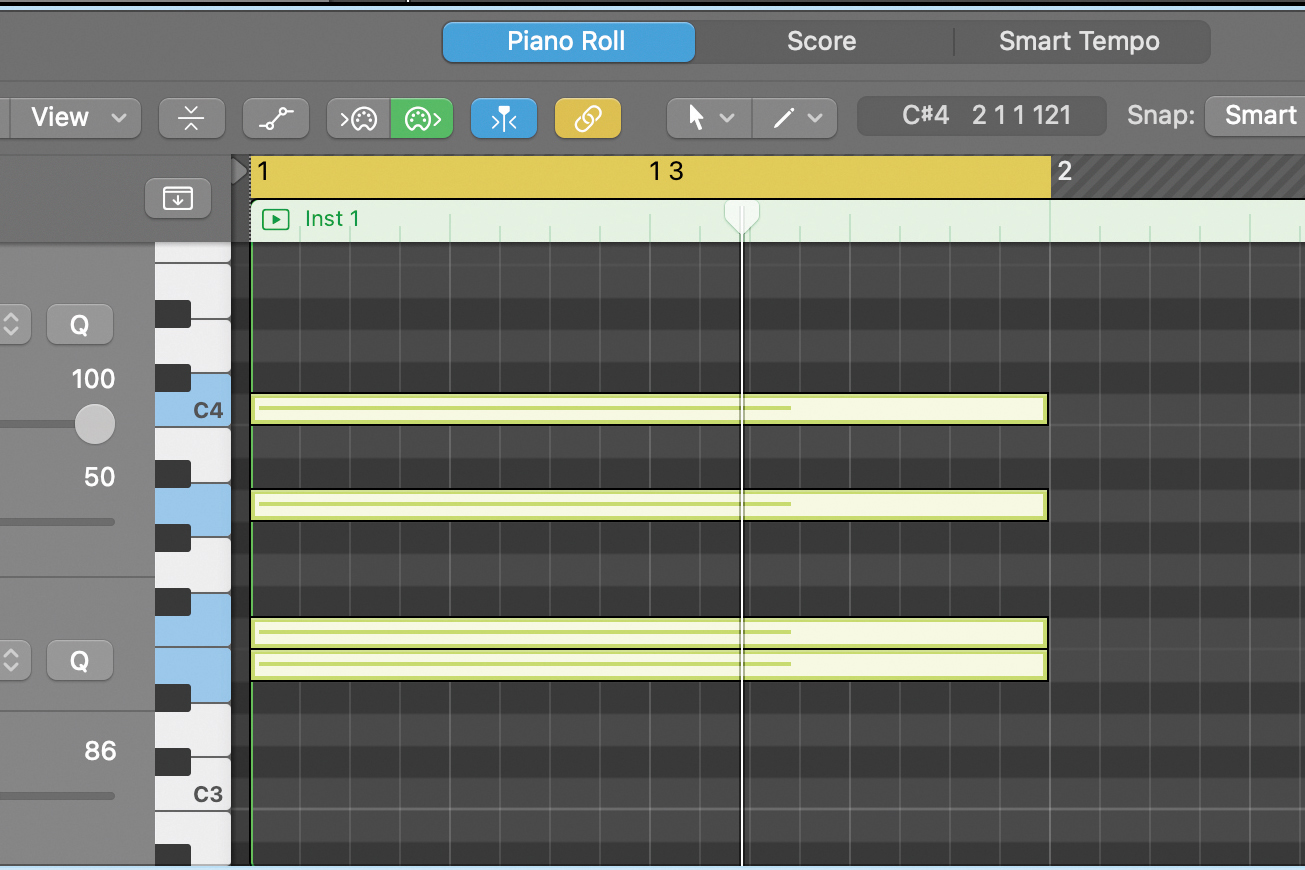

At a higher octave, let’s build a melody. We should start our melody on the same note as the bassline. Typically, the start note is the root note of your track’s key. Add a melody across the first two bars, varying pitches and note lengths for interest.

Paste your two-bar loop to the full four bars. Make a few alterations to the second half to create variety. Keep an element of repetition in your melody, whether regularly switching to the same note, or creating a rhythmic pattern.

You now have a solid four-bar melody and bassline. Build further by moving melodic notes to different octaves, adding extensions to chords, or extending your loop to eight bars. When happy, add drums to bring it to life.

Building a progression with Scaler 2.9

Music theory plugins like Scaler can seriously boost the musical sophistication of your ideas, and help you to pick up or cement music theory knowledge along the way.

We’ve listed Scaler with other music theory plugins further down the page. Although these plugins often require time investment to get them working right – as opposed to the time investment of learning the theory – many producers find learning ‘in-DAWs’ a lot more palatable.

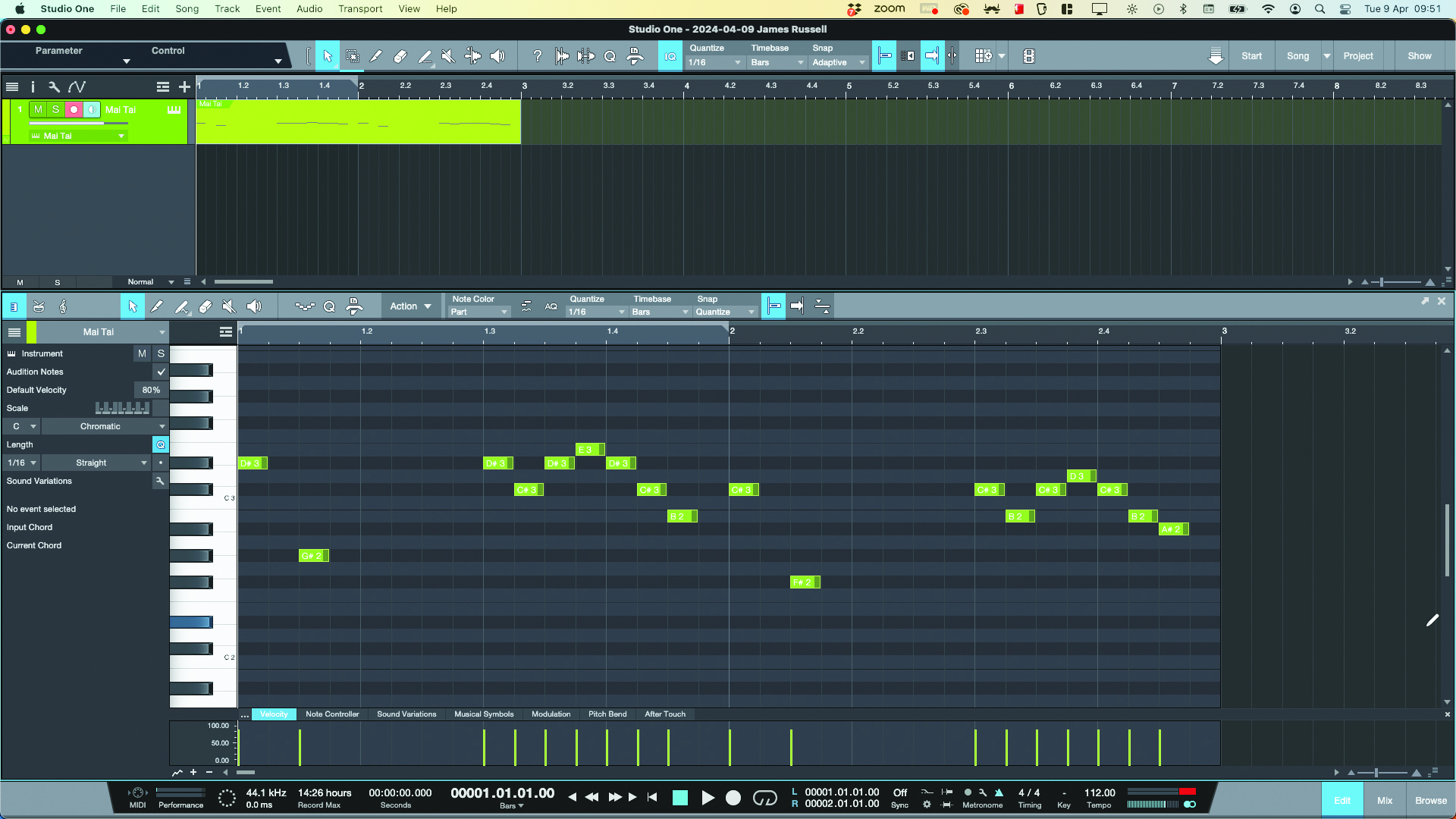

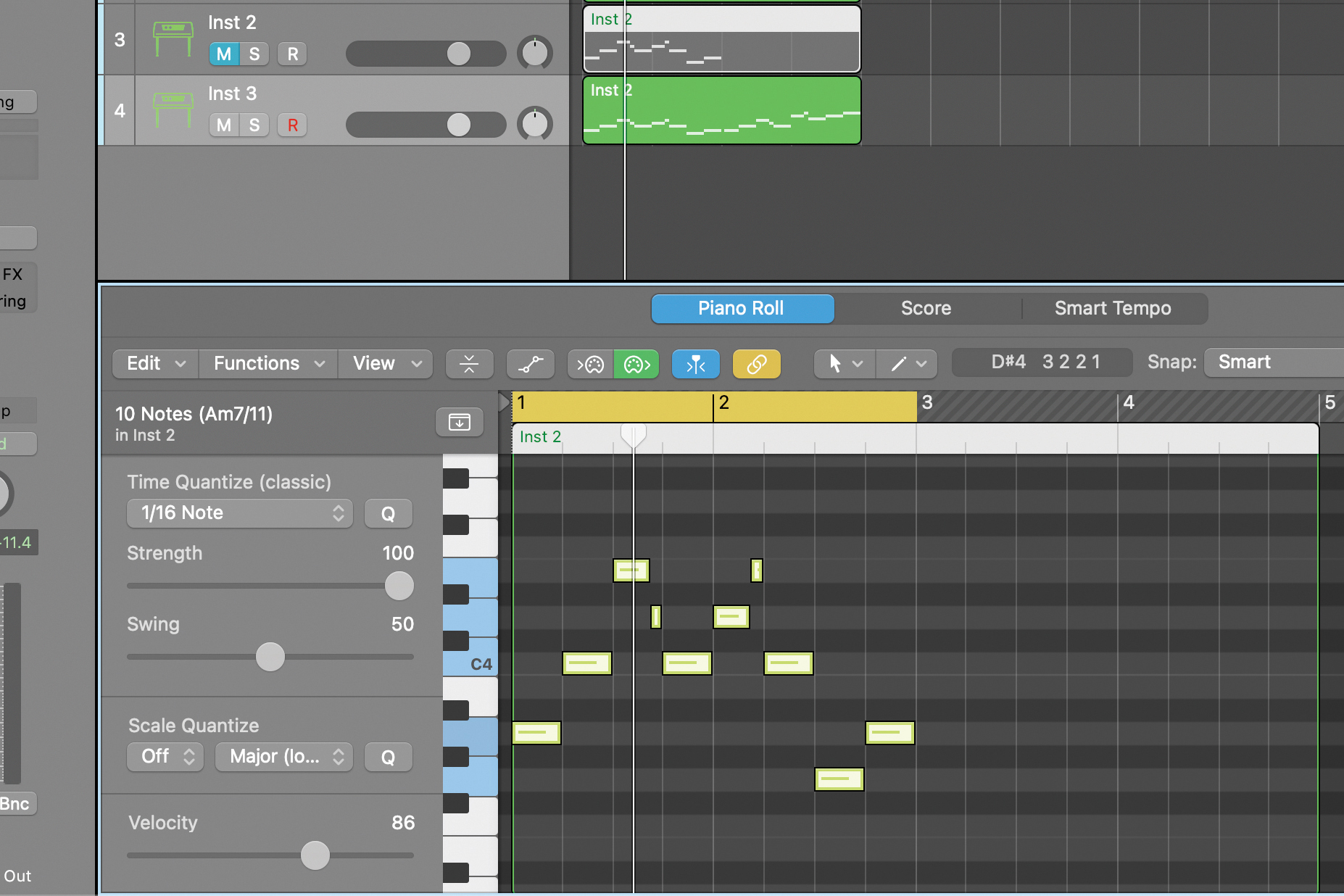

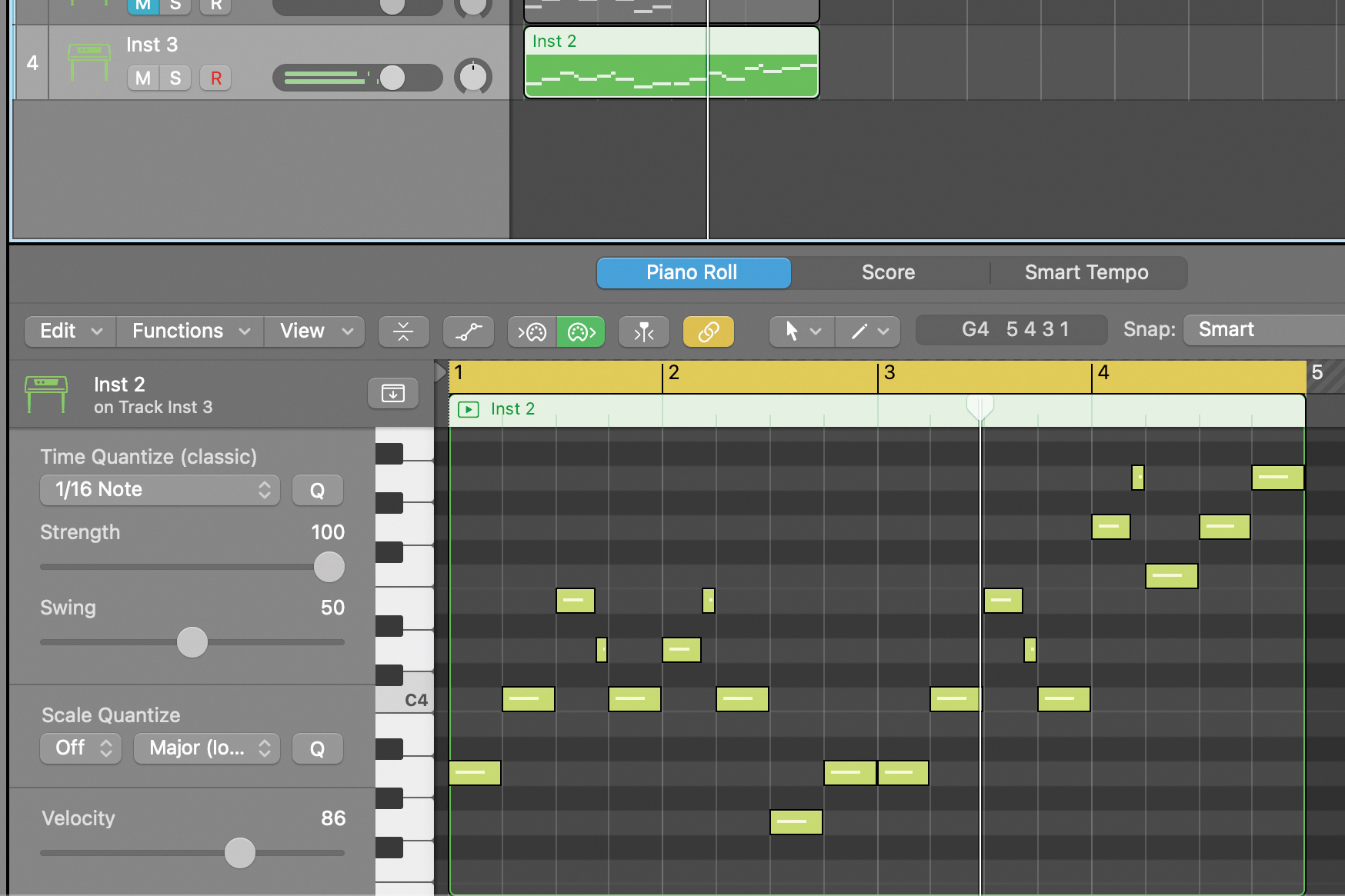

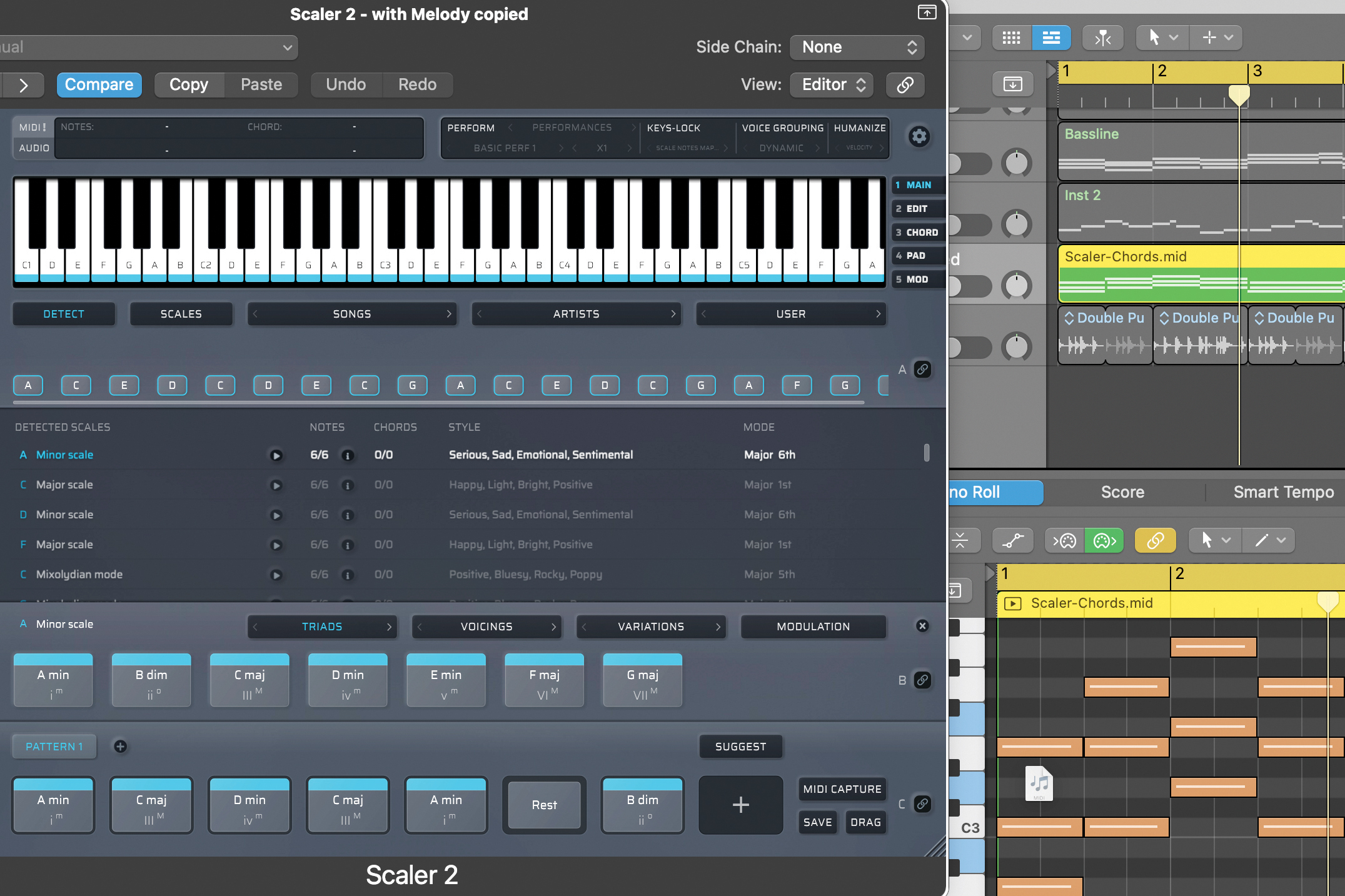

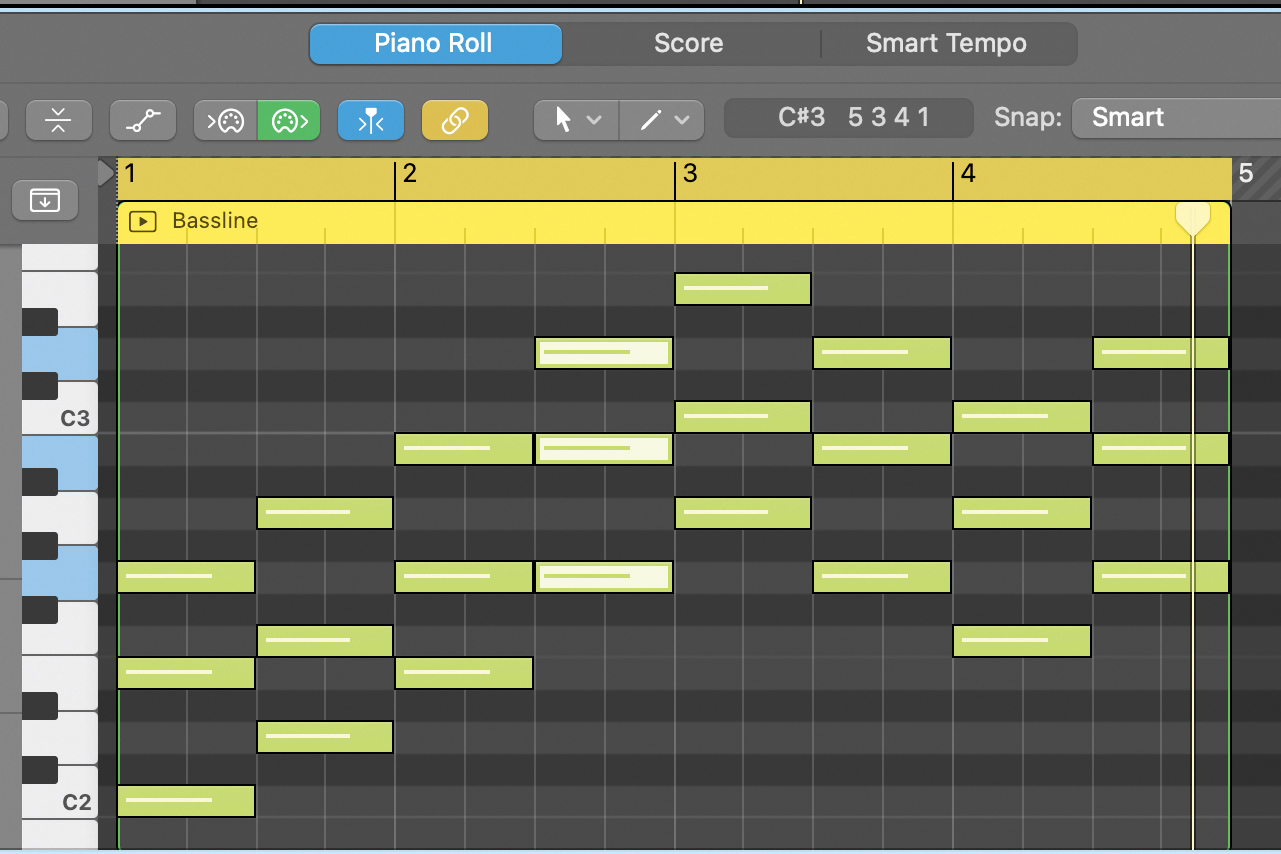

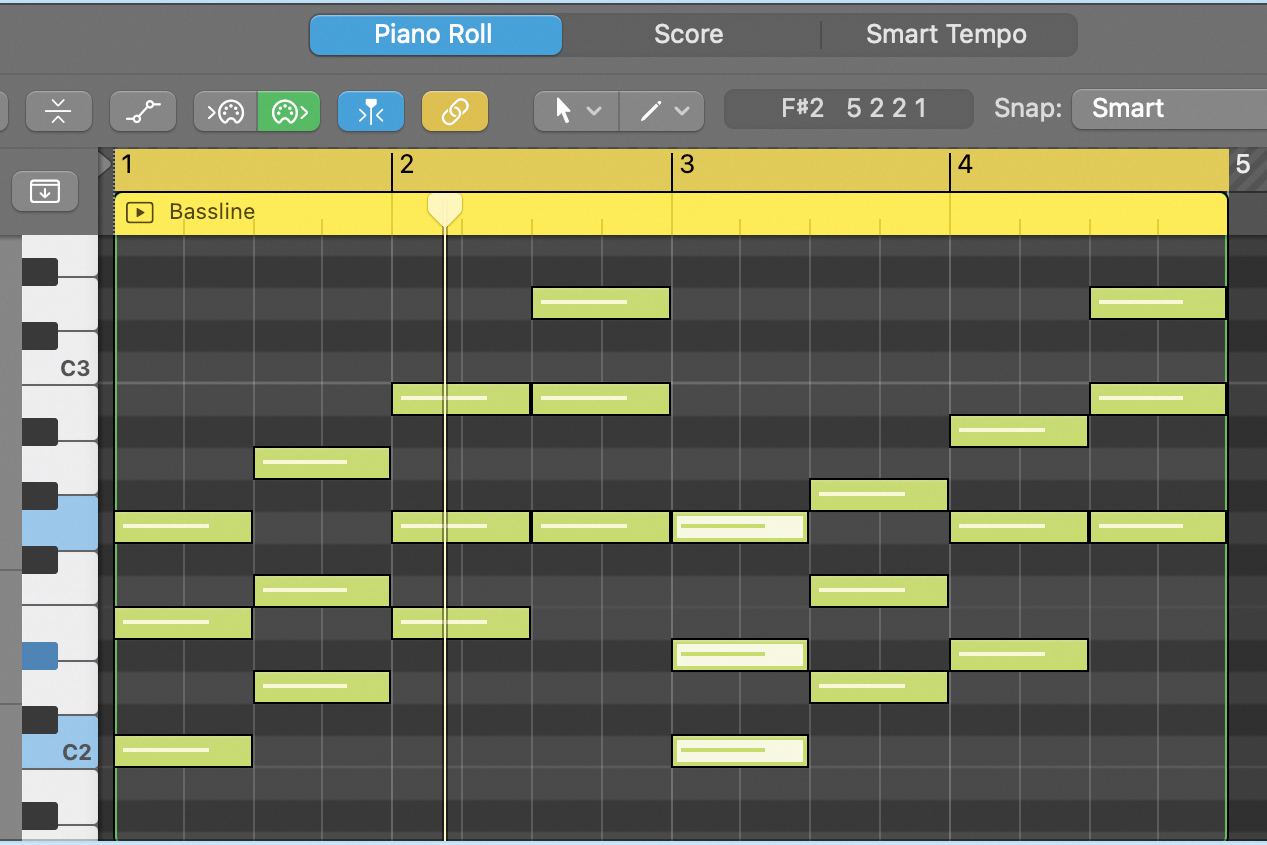

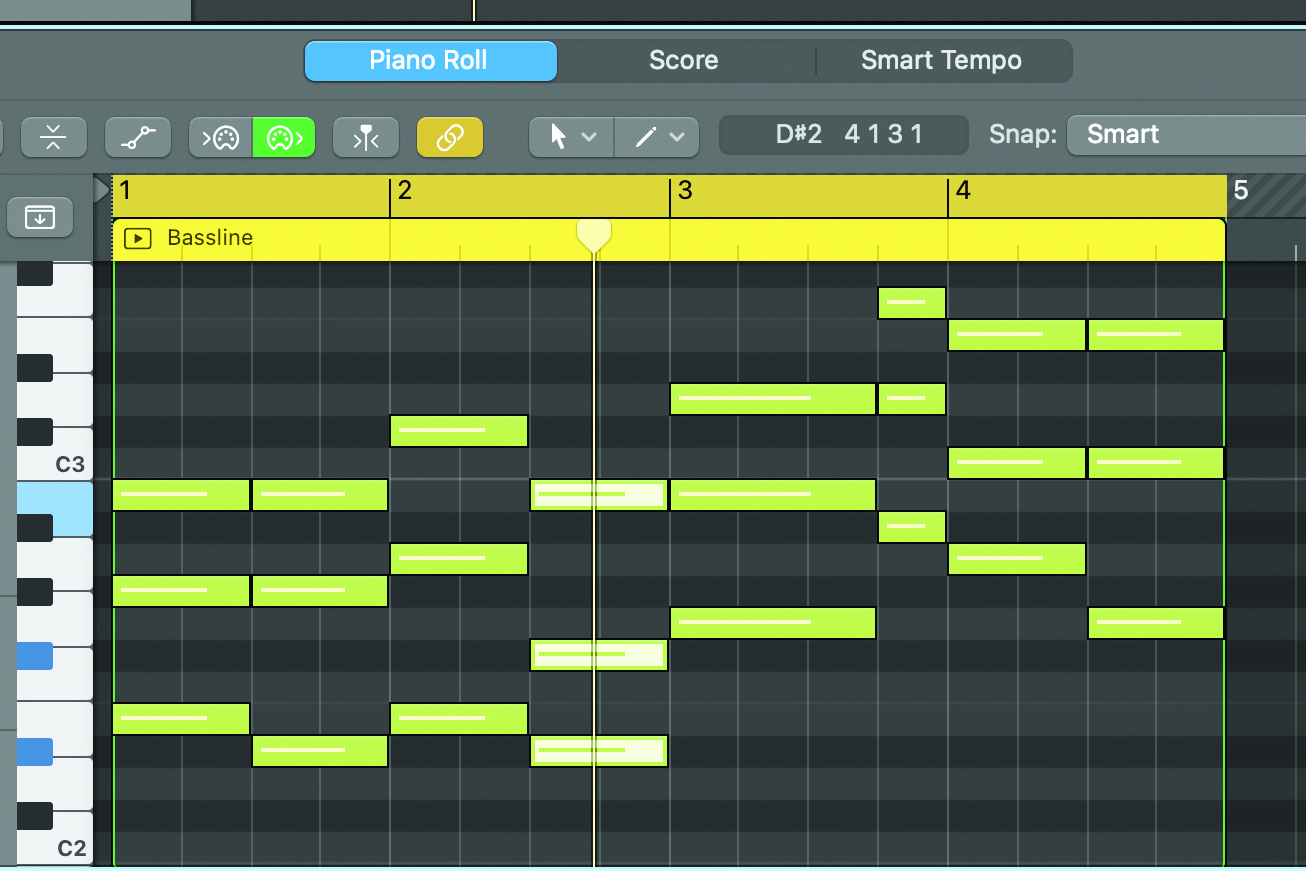

We can use Scaler 2 to build chord progressions that are true to music theory. First, if it’s a ready-made project, Scaler can detect the composition’s key. The fastest way to detect the key of a MIDI sequence in Scaler using Logic is to copy your MIDI pattern to a separate track with Scaler open.

Now set the Source (SRC) to MIDI, arm the Record button, and the MIDI Detect button, and press play until the sequence has finished. You’ll then see each note appear in order on the Scaler interface with the detected scales listed below. Our Scaler has recognised our melody as A Minor, which is correct.

Scaler lists multiple detected keys, as sometimes the inputted melody or chord progression is built from only a few notes, not a full scale. It lists detected scales in the most probable order so you can trial them. Having analysed your scale, you can access its seven chords in panel B.

Use Panel B dropdown menus to filter chord types. The first (left-hand side) drop-down menu filters between all basic triads, as well as extensions. Clicking on any chord, you’ll see the corresponding notes on the Scaler keyboard. Scaler 2 also has numerous changeable piano presets to preview audio.

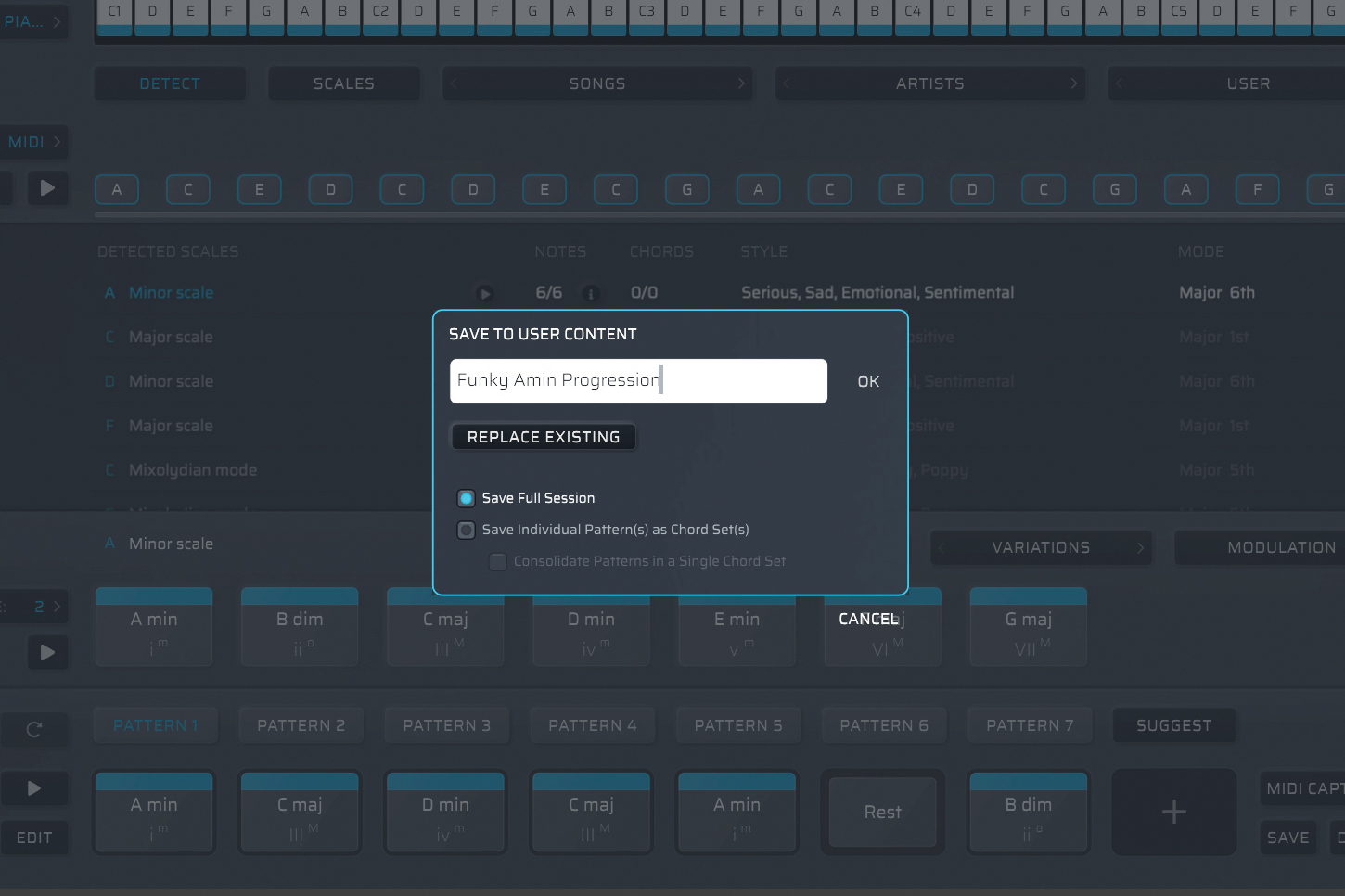

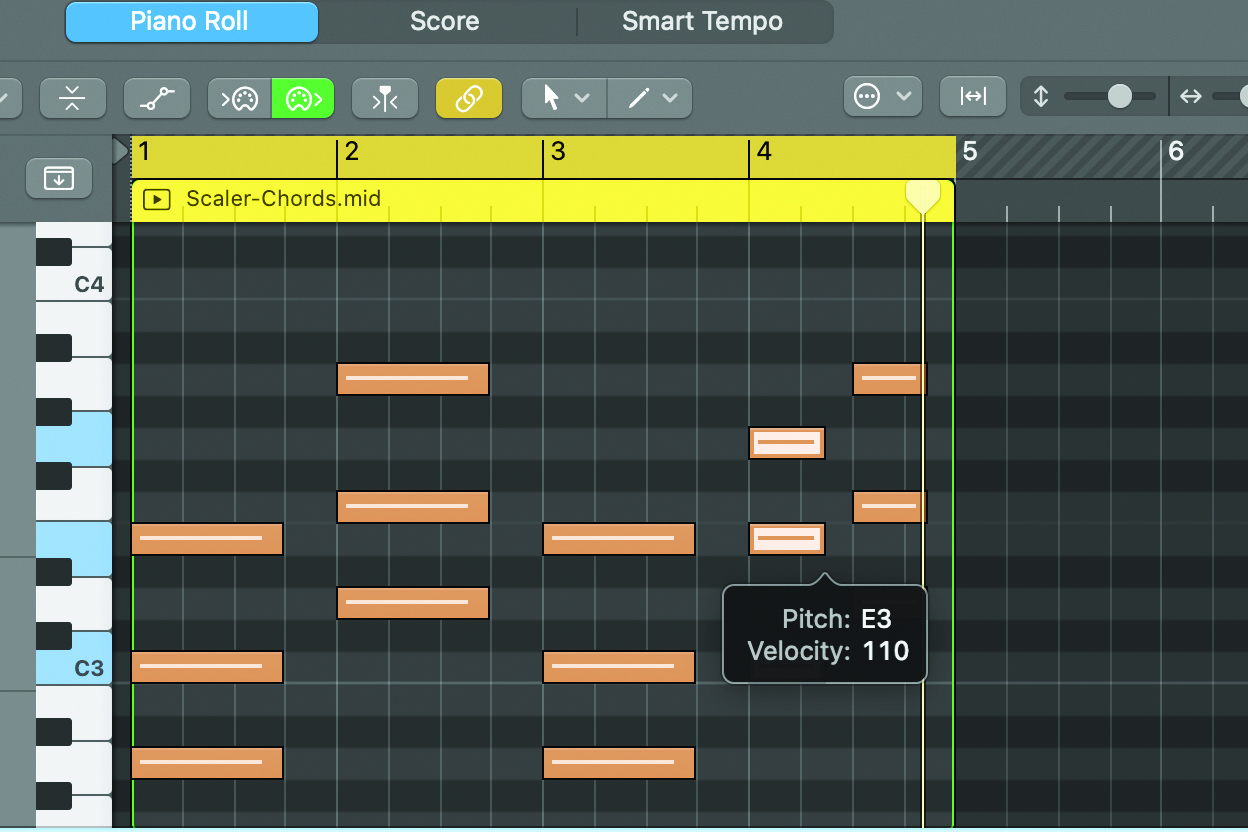

If you want to construct a chord progression inside of Scaler 2, you can use Panel C to place chords on each half measure of music. The tempo will be automatically set to your DAW bpm. Then, you can use the right-hand side Drag button to drop the data onto a track in your DAW.

You can use the second and third drop-down menus on Panel B to explore a range of chord voicing options. Switching between the menus gives you the chance to drag and drop different chord variations onto your Panel C sequence. You can have up to seven patterns loaded at a time and save them.

Once you’ve dragged a MIDI pattern into your DAW, you can make alterations. Because Scaler only allows for a chord placed per half measure, you’ll need to change chord lengths manually. You can also assign your MIDI chord progression to any desired instrument track within your DAW.

If you’re up for it, you can also switch to the modulation tab, which opens a window with suggested modulation pathways to switch keys. You can use the internal circle of fifths as a guide as well, although we haven’t covered that today. That’s some recommended further reading for you!

Changing key

Also known as modulation, changing your music’s key, mid-song, is possible when composing music. It’s used to keep a musical piece interesting: altering the conveyed emotion as the music plays. There are a few different approaches to modulation; some of them are more challenging than others, largely due to how specific keys relate to one another.

The easiest modulation method is to change between relative major and minor keys because they consist of the same notes. However, due to the similarity of relative scales, the switch is more subtle than other key changes. A more noticeable method of key change is parallel modulation. This is when we switch between scales holding the same root (or tonic) note. For instance, switching between C Major and C Minor.

Whichever method is used, a few rules apply when executing the key change. We cover four of them in our walkthrough here.

Four ways to change key

Going between relative scales relies on the major’s dominant chord. C Major’s notes are CDEFGABC; the fifth degree (dom) is G. To modulate C Maj to its relative minor (A Min), we go from the major’s dominant Gmaj chord to the minor’s tonic (Amin).

Parallel modulation relies on the fifth degree. Parallel scales (eg, C Maj and C Min) have no shared triad chords, but as both scales’ fifth note is the same (G), the major’s dominant (G Maj) can go into C Min by following it with a Cmin (tonic).

The gear shift method uses the dominant chord again, but instead of changing to a relative or parallel scale, we follow the dominant with the tonic chord of the scale that starts directly after our current scale. Eg, from E Maj to F Maj.

Finally: pivot modulation. It still relies on shared chords, but not with the dominant. Any shared chord between two scales lets us modulate. C Maj and F Maj share multiple chords. To move between the two, use any of these chords.

Three of the best MIDI plugins

1. Plugin Boutique Scaler 2

It’s the music theory assistant that has your back when composing chord progressions and detecting scales. If you’re learning, there’s a wide array of features to get to grips on music theory. Even if you’re an experienced musician, Scaler can help you whip up advanced progressions.

2. EVAbeat Melody Sauce 2

A plugin melody-writing assistant; jam-packed with an array of new features. With a redesigned UI and Advanced Editor to stencil some chords into, you’ll be able to lay down some state-of-the-art melodies, true to music theory, in no time.

3. Modalics Beat Scholar

Geared towards assisting in the drum beats and rhythm department. If you’re unfamiliar with the theory behind how beats and measures of music work, this plugin will guide you as you develop your understanding, with 250 samples to help.

A former Production Editor of Computer Music and FutureMusic magazines, James has gone on to be a freelance writer and reviewer of music software since 2018, and has also written for many of the biggest brands in music software. His specialties include mixing techniques, DAWs, acoustics and audio analysis, as well as an overall knowledge of the music software industry.