Everything you need to know about: Jungle

With a lineage encompassing everything from acid house to dancehall, jungle was more than a short-lived fad

To say that the late ’80s and early ’90s were a fertile time for UK dance music is a big understatement. And it’s crucial to understand how tech, youth culture and musical ideas collided to create these bold new sounds.

The catalyst behind much of this rapid evolution came in the form of raves, where sounds and trends changed from one week to the next, assisted by lightning-fast distribution of new music on tape packs, white label vinyl and pirate radio.

Jungle’s musical family tree is complex. The sound grew out of hardcore and breakbeat-driven forms of techno, which respectively drew influence from a range of styles including the obvious (acid house, hip-hop) along with more esoteric genres such as Belgian new beat and electronic body music (EBM).

The various roots of the jungle sound extend all the way back to ’70s reggae basslines and funk breaks, but in terms of something that might be recognised as a direct precursor to jungle, early ’90s hardcore already had most of the characteristics in place: breakbeats, chopped samples, heavy reggae-inspired basslines. Tracks like SL2’s On A Ragga Tipare clear signs of the sound emerging.

One of the final pieces of the puzzle came as ravers - possibly under the influence of illicit substances - clamoured for faster music. Average tempos crept from around 120bpm for acid house, through the 130s and 140s for hardcore, to the 150-160+ range which really defined jungle.

Welcome to the jungle

The origin of the name itself is disputed, with some claiming it as a reference to producer Johnny Jungle, others seeing it as a nod to Arnett Gardens in Kingston, Jamaica, known as the Concrete Jungle or just Jungle. The term stuck. Jungle became a distinct form, and its acolytes earned the name junglists. The junglist aesthetic - a blend of hip-hop fashion and designer clothes, graffiti and spliffs - became easily recognisable.

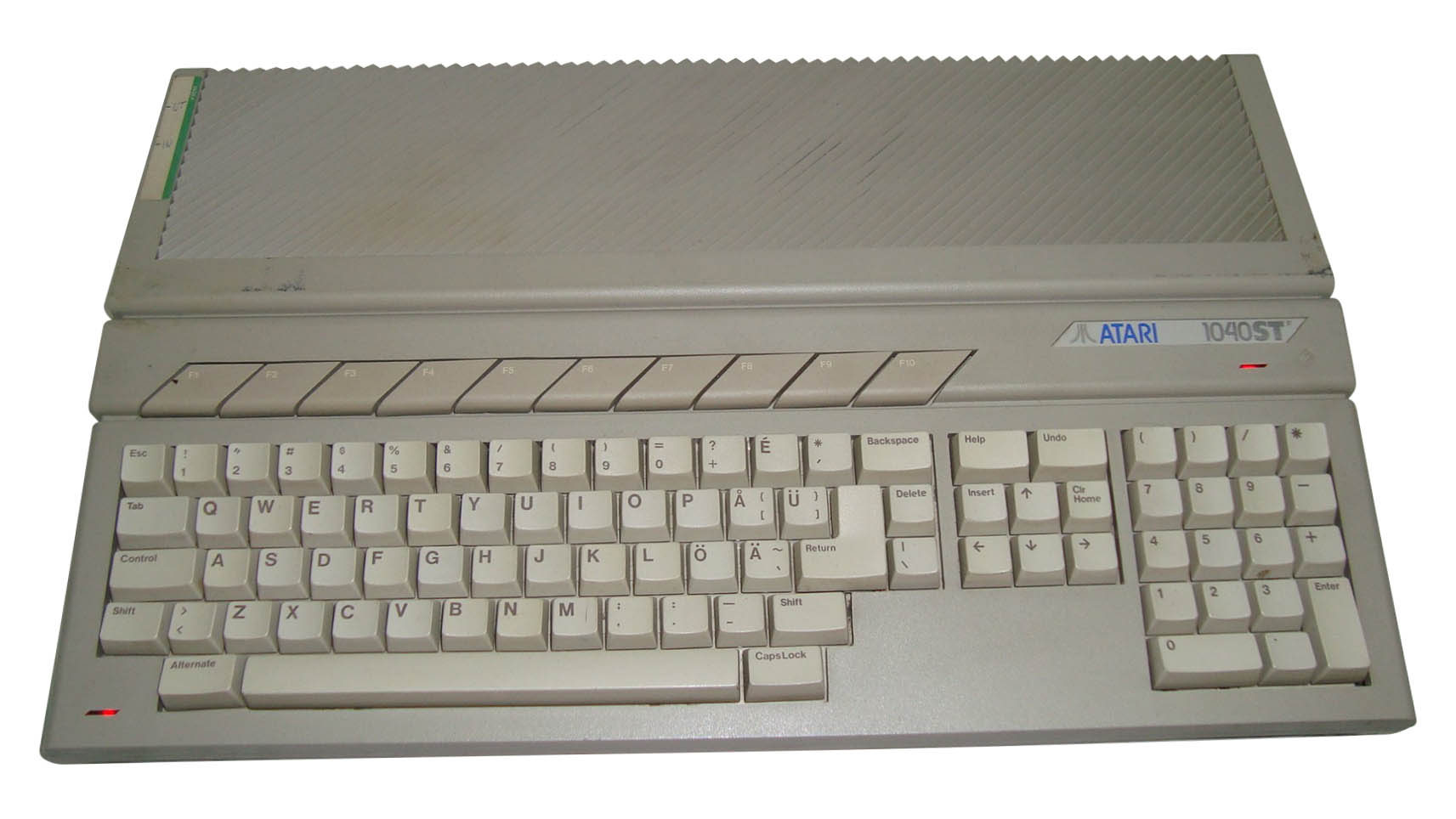

Production was rough and ready, focused around sampling rather than synths and drum machines. As such, the technological element came largely in the form of whatever sequencing and sampling technology producers could afford, mainly Atari computers and Akai samplers.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Software options for the breakbeat chopping process eventually arrived - notably Steinberg/Propellerhead’s ReCycle, released in 1994 - but slicing and rearranging samples was largely a painstakingly manual process. The ‘ruffness’ in the music came from this unpolished aesthetic, plus MC samples and vocals inspired by dancehall and ragga.

By the mid-’90s, jungle was a phenomenon. Iconic tracks like Goldie’s Terminator, Shy FX’s Original Nuttah and Dead Dred’s Dred Bass had defined a clear blueprint for the sound.

By the mid-’90s, jungle was a phenomenon. Iconic tracks like Goldie’s Terminator, Shy FX’s Original Nuttah and Dead Dred’s Dred Bass had defined a clear blueprint for the sound.

In the UK, a major sign of mainstream acceptance came as BBC Radio 1 launched a dedicated jungle show, One in the Jungle, in July 1995, the same month Goldie released Timeless, signalling a transition into a more expansive form of drum & bass. As such, some might argue retrospectively that jungle is part of the broader DnB genre.

Despite receding from the spotlight to some extent, jungle has remained a consistent reference point in dance music, playing a role in shaping the sound of UK garage and cross-pollinating back over with techno. Producers like Skream and Burial certainly took major influence from jungle as they developed their vastly different takes on dubstep. Burial’s erstwhile Hyperdub labelmate Zomby took things to extremes with whole albums of deeply retro jungle.

Revivalism lives on via producers mimicking the original early ’90s sound, but perhaps the most interesting takes come from producers like Paul Woolford under his Special Request alias, taking jungle tropes and reinventing them into fresh, exciting styles.

Three essential jungle production tools

Atari 1040ST

The weapon of choice for sequencing jungle was almost certainly an Atari, probably running either Cubase or Logic. The Atari was the people’s choice during the era, coming in at a relatively affordable price and offering built-in MIDI capabilities, plus a market-leading range of music software.

Would we still recommend producing on an Atari? Probably not. Although there are still some people who enjoy the challenge of pushing the outdated technology, it’s a frustrating and limited experience compared to a modern DAW. Very much one for the retro enthusiasts these days, rather than a serious option for most producers.

Records

We wouldn’t normally consider a record collection as an essential piece of equipment, but jungle and hardcore wear their influences with pride. In the pre-internet days of the early ’90s, it was much harder to track down music. In Europe, even knowledge of genres like hip-hop and dancehall was a status symbol, let alone owning the records and being able to sample them.

Should you still hunt down new music and rare samples? This is an easy one for producers of any type of music. 100% yes.

Akai S950

Akai samplers crop up regularly in these pages as a mainstay of various styles and genres, but forgive us for repeating ourselves once more as we include them here. It’s impossible to imagine jungle existing without the widespread availability of more affordable samplers during the late ’80s and early ’90s. Various brands and models fit the bill, but Akais were particularly popular in the UK, with models like the S900, S950 and S1000 being the main favourites.

These days, of course, you can sample much more easily in software, and that’s what we’d recommend in most cases. But there’s still lots of fun to be had chopping breakbeats and getting to grips with the more convoluted workflow of a hardware sampler. Some argue it’s impossible to match their unique sound, too.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.