“My God, it’s hard to get in tune when they’re booing": when Bob Dylan faced down his detractors with a Strat and made rock n' roll history

In 1965, Bob Dylan strapped on a Stratocaster, then a Telecaster, and ushered in a bold new folk-rock sound. But he'd actually gone electric six months earlier…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

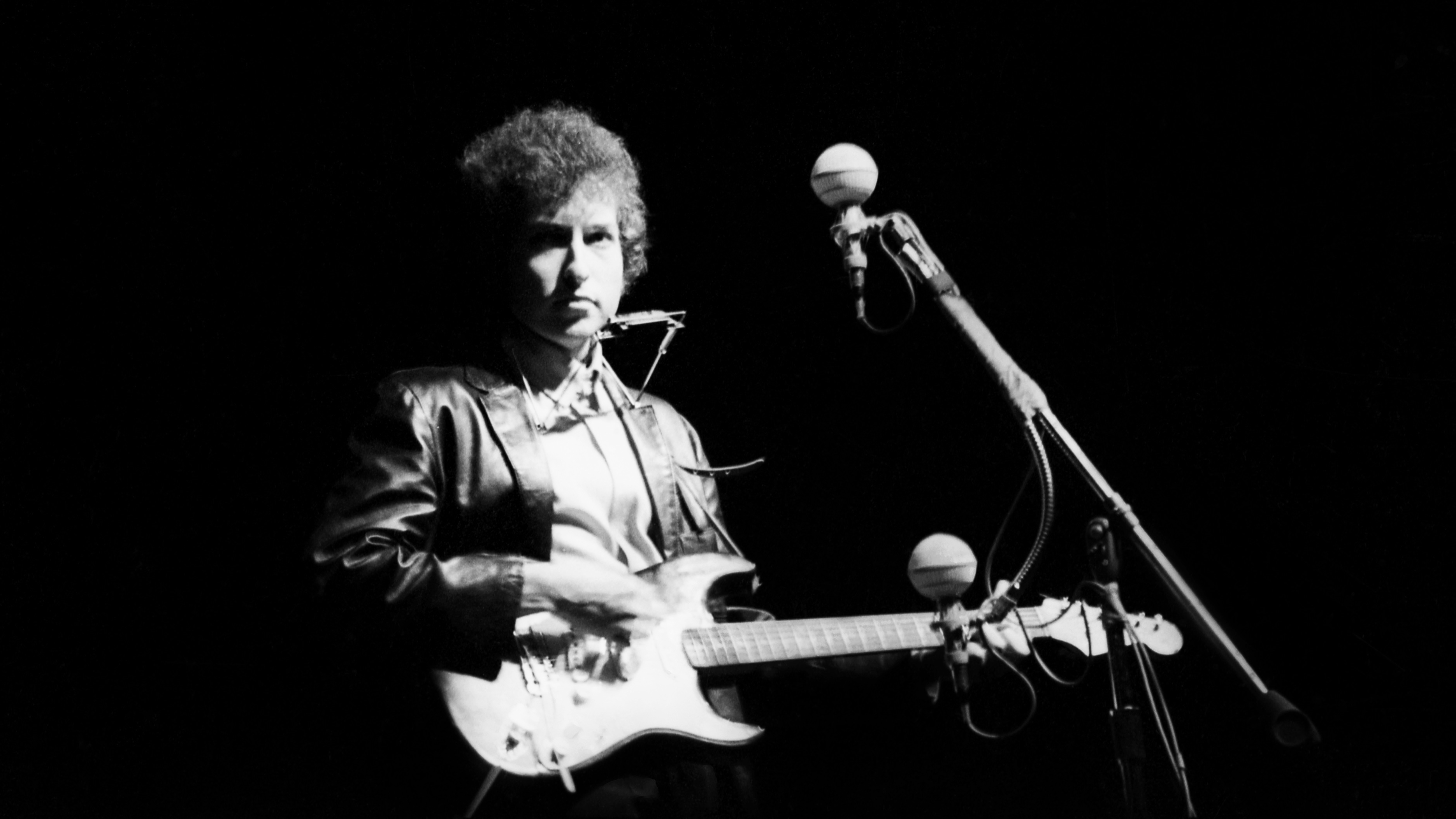

Late in the evening of 25 July, 1965, Bob Dylan strode out onto a darkened stage at Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island wearing black jeans, black boots and a black leather jacket. This was his first ever performance playing electric guitar and strapped around his neck was a 1964 sunburst Fender Stratocaster. Dylan was flanked by guitarist Mike Bloomfield, organist Al Kooper and various members of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. What followed has become the stuff of legend.

Dylan and the band tore straight into a storming version of Maggie’s Farm, from Dylan’s fifth album Bringing It All Back Home, released in March that year. Between each of Dylan’s vocal lines, Bloomfield reeled off searing Chicago blues-style lines on his Telecaster.

By today's standards, the volume wasn't particularly high, but in 1965 it was probably the loudest thing anyone in the audience had ever heard

Joe Boyd

Accounts vary wildly but one thing seems certain: when Dylan and the band finished the song there was as much booing as there was applause from the 15,000-strong crowd.

“By today's standards, the volume wasn't particularly high, but in 1965 it was probably the loudest thing anyone in the audience had ever heard,” recalled record producer and writer Joe Boyd in his memoir White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. “A buzz of shock and amazement ran through the crowd… There were shouts of delight and triumph and also of derision and outrage.”

For the folk purists, it was verging on heresy. In their view rock was puerile and crass, and true authenticity could only be attained on acoustic instruments.

Dylan and the band didn’t hang around to ponder this. They hurtled straight into Like A Rolling Stone, his new radio hit. Each time he sang “How does it feel?”, the audience let him know exactly how they felt. The third song, an early version of It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry, was their last. Dylan and the band bolted from the stage. He was the headline act but he had been on stage for only 17 minutes.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen, but they certainly booed, I’ll tell you that,” Dylan told a press conference in San Francisco five months later. “You could hear it all over the place.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Backstage there was confusion, while out front, the crowd were getting louder, most people now feeling betrayed that the headline act had played three songs and then vanished.

Dylan was urged to return and went back out with a borrowed acoustic, performing Mr Tambourine Man and It’s All Over Now Baby Blue. He got a rapturous applause, but he was visibly shaken.

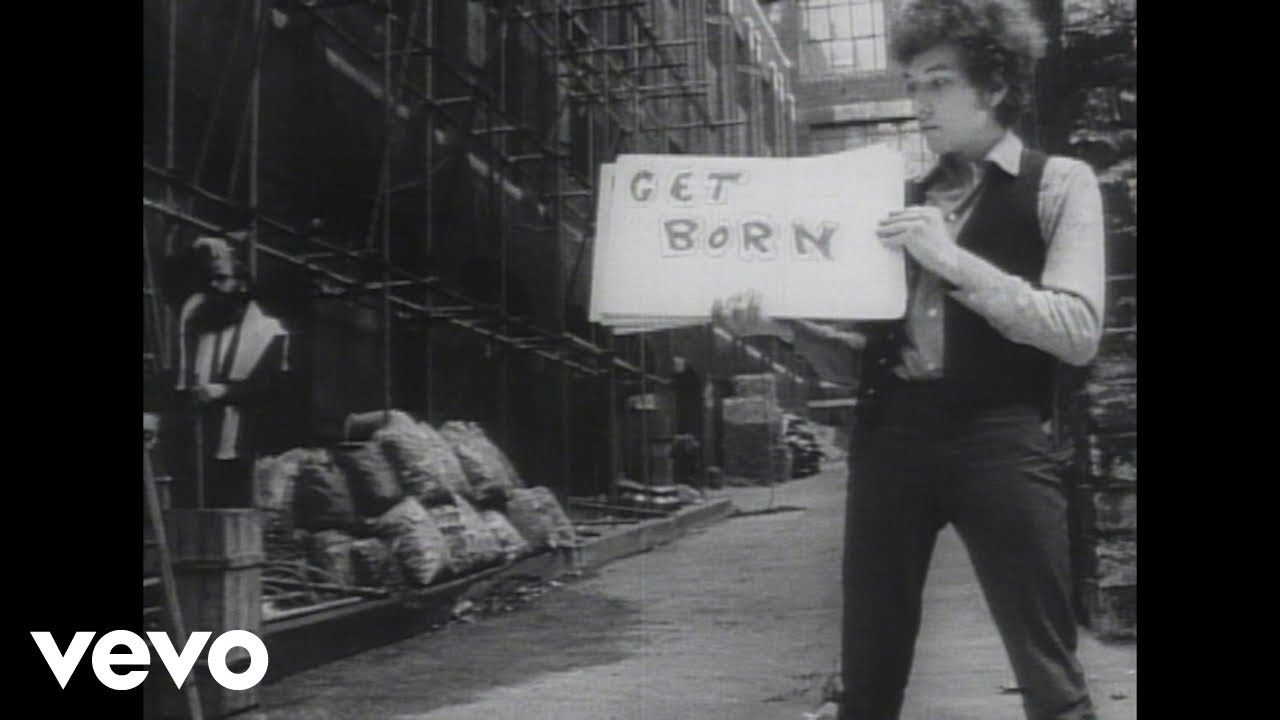

The Newport Folk Festival is regarded as the moment that Dylan turned electric but it all really started six months earlier on 14 January 1965, a bitterly cold day in New York, when Dylan ventured over to Studio A at Columbia Studios, at 799 Seventh Avenue. It was the second day working on his fifth album, Bringing It All Back Home, and he laid down the first song on the album, Subterranean Homesick Blues No. 10.

Clocking in at just two minutes and 22 seconds, it’s a raw slice of rockabilly-fuelled brilliance with rapidfire lyrics delivered deadpan-style by Dylan. When asked about the inspiration for the song by Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times in April 2004, Dylan said: “It’s from Chuck Berry, a bit of Too Much Monkey Business and some of the scat songs of the ‘40s.”

Backing Dylan were John Hammond Jnr and Bruce Langhorne on electric guitars, Bill Lee on bass, Bobby Gregg on drums and an unidentified pianist. It took just one take and it was a seminal moment. As Richard Williams of The Guardian put it: “In two minutes and 22 seconds of jangling, rickety-rackety, homemade folk-blues-rock, something new was born.”

The next step was to take this new material out on tour. That’s when the problems really began

Bringing It All Back Home is split into two distinct halves, the first featuring electric instrumentation while the second is acoustic-based. The album reached No. 6 in the US Billboard 200 and No. 1 in the UK Album Chart. The next step was to take this new material out on tour. That’s when the problems really began.

In late summer 1965, on the advice of Mary Martin, a receptionist for Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman, Dylan went to Toronto to check out a band called Levon & The Hawks, who had served their time as The Hawks, backing rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins in ballrooms, bars and juke joints across the length and breadth of North America.

Dylan needed a new guitarist and drummer, and was impressed by The Hawks’ guitarist and songwriter Robbie Robertson and its drummer, singer and multi-instrumentalist leader, Levon Helm. The two joined Dylan’s band, beginning by playing a number of shows in the US, including one at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in Queens, New York on 28 August, 1965, where they debuted new song Desolation Row, from his sixth studio album Highway 61 Revisited.

According to journalist Jeff Slate, writing in Esquire magazine in July, 2016, when Dylan and the band launched into Maggie’s Farm, some people attempted to rush the stage, before being stopped by police. Al Kooper was knocked off his stool by a fan fleeing from the police. Fruit was thrown and there were allegedly shouts of “traitor”, “scumbag” and, bizarrely, “where’s Ringo?”

Kooper quit, citing stress and safety concerns, and by the end of November 1965, Levon Helm too had gone, disillusioned by the relentlessly hostile reception.

Dylan recruited the rest of Levon and the Hawks – Rick Danko (bass, guitar, vocals and fiddle), Richard Manuel (piano, organ vocals and drums) and Garth Hudson (keyboards, saxophone, accordion, woodwind and brass). Dylan’s new backing band would soon be renamed The Band.

In February, 1966, Bob Dylan and The Band embarked on a tour of Australia, Scandinavia, Europe, the UK and Ireland. Throughout the tour, Dylan firstly performed an acoustic set, using his rare 13-fret Gibson Nick Lucas Special, which he bought in 1963 in New York.

This was followed by an electric set with The Band, with Dylan playing a black 1965 Telecaster with white scratchplate and maple neck, through a Fender Showman amp. Five years later, Robertson would strip the original black finish back to bare wood, and add modifications such as a Gibson PAF humbucker and a Bigsby B16 vibrato tailpiece.

The tour got under way, but the hostility from audiences continued. Their dislike of Dylan’s electric sound is evident from the footage captured by D.A. Pennebaker for his 1967 documentary Don’t Look Back, an account of Dylan’s 1966 tour. Previously unseen footage by Pennebaker is used in Martin Scorcese’s 2005 documentary No Direction Home. It’s mesmerising to watch.

I think he’s prostituting himself

As Dylan and The Band finish Like A Rolling Stone at the Odeon Theatre in Newcastle on 21 May, 1966, loud boos can be heard as they leave the stage and the National Anthem strikes up over the house PA.

“He’s changed from what he was, he’s not the same as what he was at first,” says one bewildered fan. It was a similar story in Sheffield five days earlier. “I don’t know what he’s trying to do,” said one. “I think he’s conceding to some sort of popular taste. I think it’s a bad thing. I think he’s prostituting himself.”

“It makes you sick listening to this rubbish now,” said one audience member, while another put it more bluntly: “Bob Dylan was a bastard in the second half.”

One fan was as unimpressed by Dylan’s acoustic set. “I found there was too much improvising on his wretched harmonica and he tended to lose the rhythm altogether on his guitar at times.”

As was the case at the Newport Folk Festival, audiences were split in their opinions. “Rank”, “lousy”, “fantastic” and “excellent” were four verdicts from fans in the Pennebaker footage.

The filmmaker also managed to capture the infamous moment, at Manchester Free Trade Hall on 17 May, 1966, when a heckler, incensed by Dylan’s switch from folk to rock, shouts out “Judas”. “I don’t believe you – you’re a liar”, retorts Dylan before turning to the band and telling them to “Play fucking loud!”

For Dylan and The Band, it was all taking its toll. As he and Robertson are whisked away in a car from one of the shows, Dylan jokes “Don’t boo me any more. The booing, I can’t stand it. My God, it’s hard to get in tune when they’re booing. Jesus, I can’t understand, how can they buy the tickets up so fast?”

Usually in a case like this, you would say, ‘You know what? The audience isn’t really gravitating toward this. Maybe we should change some things’. No!

Robbie Robertson

By the time they played their last two UK shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall on 26 and 27 May 1966, the hostility had taken on its own momentum and there were walkouts. “What happened to Woody Guthrie, Bob?” someone shouted. “These are all protest songs, now come on,” implored Dylan.

For The Band, it was a baptism of fire. “People [were] booing and throwing stuff every night,” Robbie Robertson told SiriusXM host John Fugelsang in 2019. “And we’re just going along. It was called just play louder and faster and everything. And it was kind of like a rebellion.”

One year on from his performance at Newport, on 29 July 1966, Dylan crashed his motorcycle near his home in Woodstock, New York. It’s been argued by biographers that the crash gave him the chance to escape the pressures around him. It would be eight years before he toured again.

One week earlier, at the 1966 Newport Folk Festival, several electric bands took to the stage such as Lovin’ Spoonful, Howling Wolf, Chuck Berry and the Blues Project. Not an eyebrow was raised. The festival had moved on and so had the music scene.

Dylan was a torchbearer for the genre that became folk-rock but he incurred the wrath of folk purists. To his credit, he was steadfast in his creative quest. In the process, his influence helped pave the way for other cross-genre cultural high points, such as Rubber Soul, that would follow in his wake.

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.