The beginner's guide to: dancehall

We investigate how Jamaica’s dancehall became an important part of modern pop and hip-hop

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sice the 1960s, Jamaican music has consistently punched above its weight on a global scale. From ska to reggae, dub and beyond, the Caribbean island nation with a population of less than three million people has influenced the world.

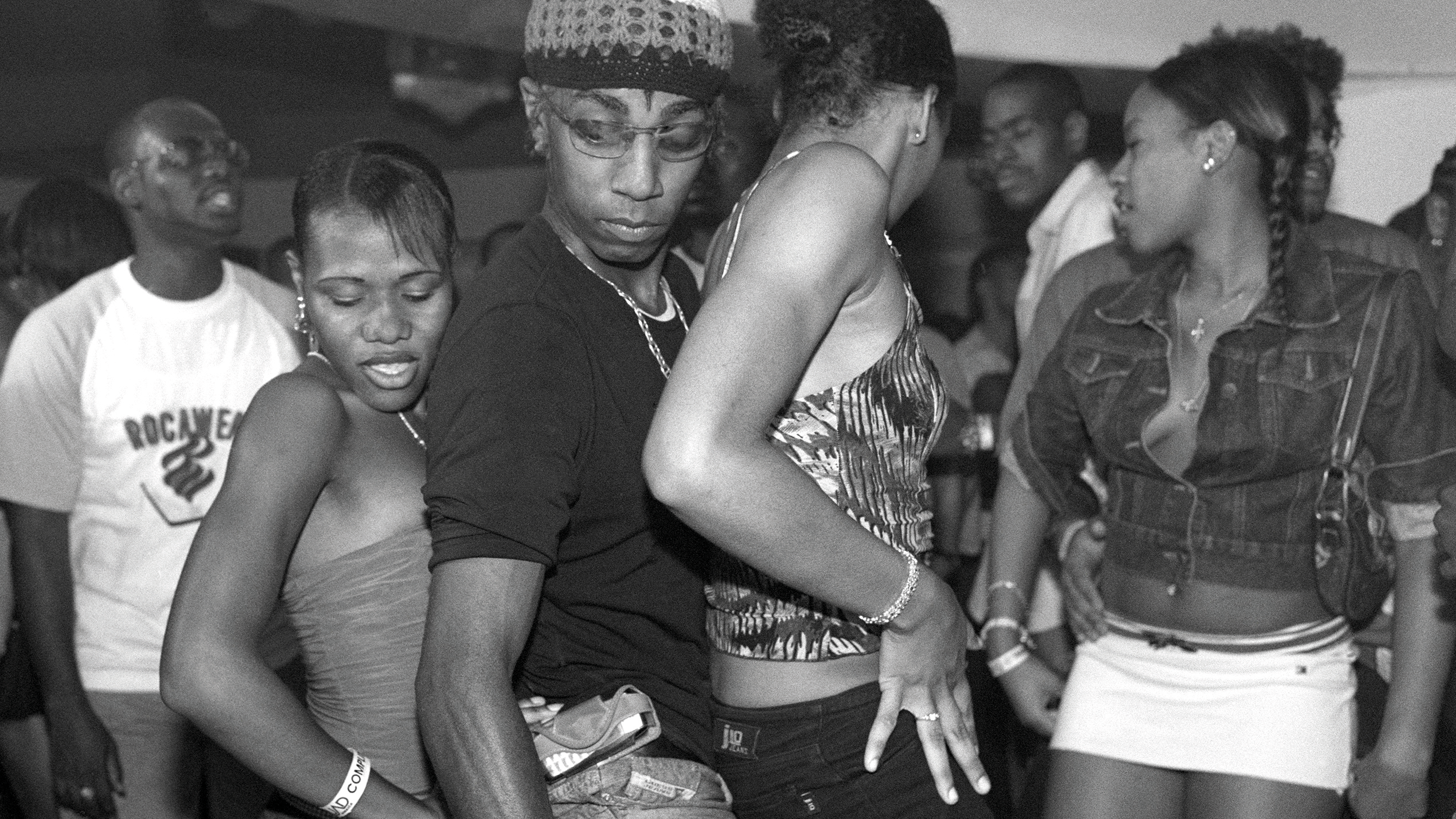

Much like the evolution of dub from reggae, dancehall began as an offshoot of the dominant roots reggae sound of the late 1960s and early ’70s. As the name suggests, its origins lay firmly in the dance halls of Jamaica, where reggae evolved into a more party-focussed style that emphasised upbeat musical backings for ‘deejays’ (vocalists) to perform over.

On the Jamaican musical spectrum, you could say that dancehall sits somewhere between the traditional roots reggae of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, and the dub of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Augustus Pablo. Since dancehall is unabashedly party music, it evolved into its own distinct genre.

Despite sounding very different, there are numerous similarities between dancehall and the more downtempo, almost trippy sound of dub, not least in terms of the reliance on ‘riddims’, popular instrumental backings which are reused by numerous artists to create different songs based on similar or even identical instrumentals.

The dance element of dancehall shouldn’t be overlooked, with dance crazes playing just as important a role as the riddims themselves (and often being directly linked to each other). Cited by Beenie Man as the greatest dancer of all time, Gerald ‘Bogle’ Levy was possibly the most influential character in the development of dancehall’s dance trends, responsible for his signature bogle dance among many others.

Dancehall isn’t particularly loyal to any specific tech or instrumentation, making it a notably diverse genre in terms of sound. There are riddims which stick closely to the organic instrumentation of roots reggae and others which are more influenced by other genres, such as R&B (Miss Independent riddim, inspired by the Ne-Yo hit of the same name) and pop (Faith riddim, inspired by George Michael). From the mid 1980s onward, the digital dancehall revolution marked a shift in style to synths, drum machines and other ‘digital’ instrumentation.

Vocally, dancehall is equally diverse, with an emphasis on ‘toasting’ – the uniquely Jamaican rap-like vocal style also frequently heard in dub – but also singing and more US-influenced rapping styles. Lyrically, dancehall has rarely been without its controversies, having been accused at various times of glamourising violence and gang culture, promoting misogyny and even of fostering homophobia.

All of these criticisms are undoubtedly true to some extent, but a broader view of dancehall might argue that such negativity is thankfully a very small aspect of the genre rather than a defining feature. It’s also well worth noting that dancehall has fostered careers of female artists from Sister Nancy to Lady Saw and Spice, each representing female empowerment in their own personal way.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

As with so many of the genres we’ve explored – and much like other Jamaican styles including ska and dub – dancehall has been hugely influential on a global scale. Aside from obvious commercial success for Jamaican artists like Vybz Kartel, Popcaan and Alkaline, you can see the influence on Diplo’s EDM crossover project Major Lazer, or UK rapper Stefflon Don.

Beyond the direct spread of dancehall sounds, you can hear numerous instances of pop artists adopting dancehall sounds, from Drake’s Beenie Man-sampling Controlla to Rihanna’s huge 2016 hit Work. As with so many other Jamaican styles since the mid 20th century, dancehall’s global impact is gigantic.

Three classic dancehall riddims

Sleng Teng

Produced by King Jammy and Wayne Smith and popularised by the latter’s iconic track Under Mi Sleng Teng, the Sleng Teng riddim was largely responsible for kicking off the digital dancehall craze in the 1980s.

Sleng Teng is notably based around a rockabilly-influenced preset pattern found on the humble Casio MT-40 keyboard, widely believed to be influenced by Eddie Cochran’s 1959 song Somethin’ Else. Casio’s Hiroko Okuda denies that link, suggesting that the distinctive riff may have been inspired by David Bowie’s Hang On to Yourself.

Real Rock

Arguably the first reggae riddim to cross over into early dancehall, Real Rock was a 1967 instrumental by Sound Dimension whose simple Hammond organ melody and loping groove were adapted by hundreds of other artists, from Augustus Pablo to The Clash to Bounty Killer.

Diwali

Characterised by its distinctive syncopated clapping pattern, the Diwali riddim was one of the most recognisable sounds of pop music in 2002, spawning hits including Sean Paul’s Get Busy, Wayne Wonder’s No Letting Go, Rihanna’s Pon De Replay and Lumidee’s Never Leave You (Uh Oooh, Uh Oooh).

Originally produced by Steven ‘Lenky’ Marsden, some of the most famous tracks performed over the riddim were compiled on Greensleeves Rhythm Album #27, part of the London-based label’s long-running series which released 90 riddim-focussed albums between 2000 and 2010.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.