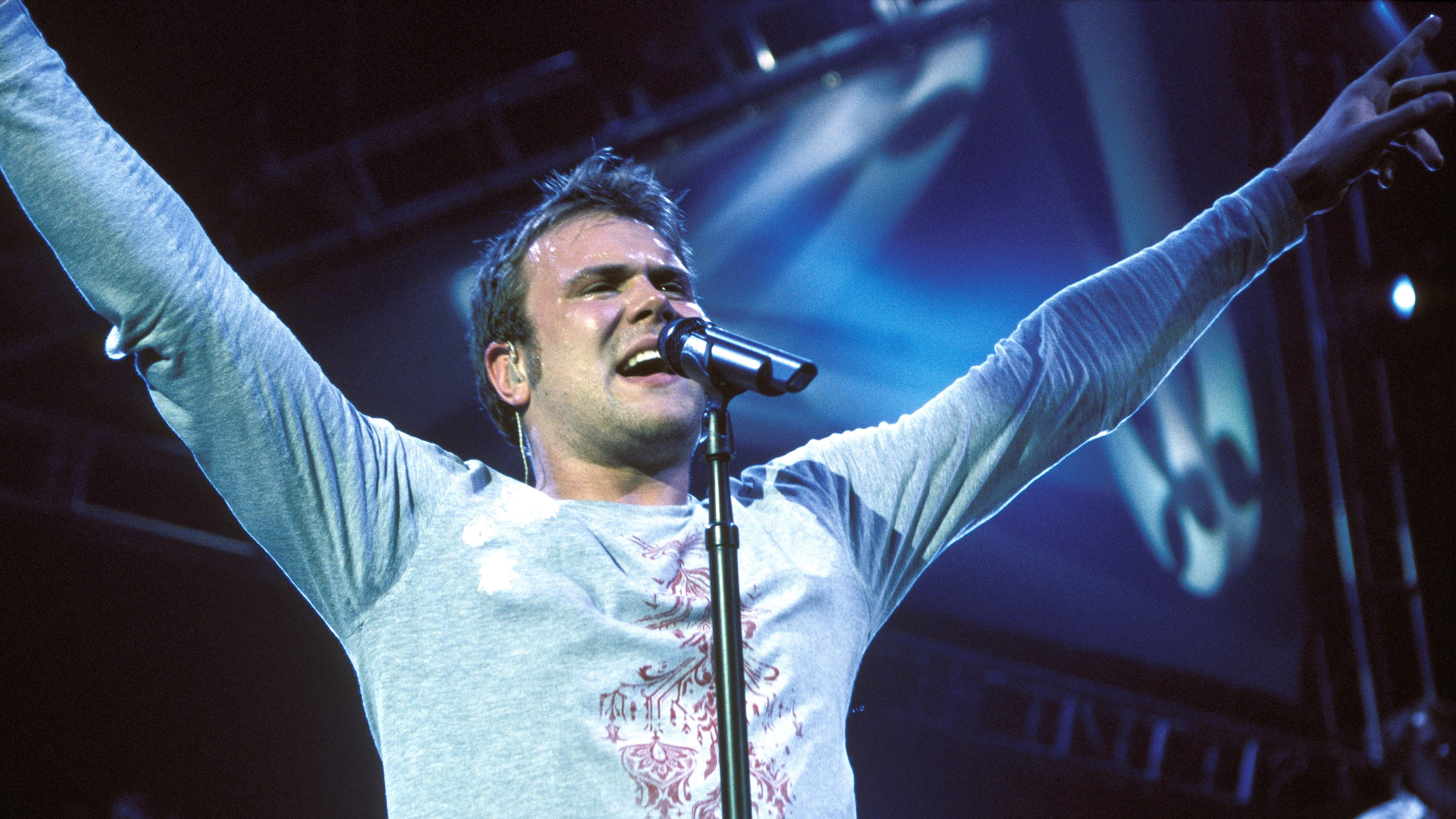

“Seriously, I recorded half of that album in my underpants”: How Daniel Bedingfield's bedroom-produced No. 1 rewrote the rules of pop - before he disappeared for decades

Before Billie Eilish, there was Daniel Bedingfield. Here's how Britain's first bedroom popstar made chart history

In 2025, the idea of a bedroom-based artist crafting a No. 1 hit from the comfort of their own home isn’t a far-fetched concept.

Music-making software is advanced and easily affordable, and plenty of DIY artists have found worldwide success with tracks produced with nothing but a laptop - hell, all Steve Lacy needed to record the chart-topping, Grammy-nominated Bad Habit was an iPhone.

Back in 2001, though, this kind of homegrown hitmaking was practically unheard of. Although electronic musicians had been experimenting with bedroom production for much of the previous decade (The Prodigy cracked the UK Top 10 with the cartoon-sampling Charly all the way back in 1991) a home studio creation had only reached No 1 once, with White Town's Your Woman in 1997. It wasn't until Daniel Bedingfield sat down in his underpants in 2002 and put together the history-making UKG smash Gotta Get Thru This on his home computer that the floodgates opened and the era of bedroom production began in earnest.

While tracks like Charly were produced using hardware-based set-ups in the ‘90s, the turn of the millennium brought with it rapid advancements in music-making software. As DAWs grew more sophisticated and more affordable for the average musician - becoming something you might find on a home PC, rather than a professional studio - it soon became possible to craft entire albums with nothing more than a desktop computer and a copy of Cubase or Reason.

"I did the whole song in my head, so I had to keep singing it all day - I rushed straight home after work and put it down"

Or, in Bedingfield’s case, a copy of Making Waves, an obscure DAW descended from ‘80s trackers that featured a sequencer, sampler, mixer and audio editor, along with basic MIDI and VST support. “It was an amazing time for technology,” Bedingfield told Ticketmaster last year. “That programme I used was hardly even out, it was just a beta of this software called Making Waves.”

Armed with this basic set-up and a cheap microphone, all the 22-year-old Bedingfield needed was an idea - something that arrived in a lightning bolt of inspiration while he was rollerblading across London’s Tower Bridge on the way to work. “The rhythm of the song (da da da da) was how I was skating, and the song came to me in its entirety, except for the bridge.” Bedingfield recalls. “I did the whole song in my head, so I had to keep singing it all day - I rushed straight home after work and put it down.”

Embroiled in a challenging long-distance relationship with a partner halfway across the country, the aspiring songwriter drew on his romantic troubles for lyrical inspiration, but the song’s production was influenced by a different source. “I’d been going to drum ‘n’ bass gigs and garage nights twice a week for the whole three years, just learning how to make garage. I would take my records and give them to DJs to ask what could be better,” Bedingfield says.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Gotta Get Thru This was a dynamic fusion of pop, R&B and UK garage, a once-underground style that had earned mainstream recognition by the time Bedingfield recorded his breakout release. Influential tracks like Artful Dodger and Craig David’s Re-Rewind and Shanks & Bigfoot’s Sweet Like Chocolate paved the way for Gotta Get Thru This with swung 2-step beats with addictive vocal hooks, setting a template that dominated the charts throughout the early ‘00s.

Once Gotta Get Thru This was recorded, the enterprising artist burned a handful of promo CDs and handed them to DJs in the hopes of getting played in a few sets across London. Little did he know, within a few months the song would reach No. 1, going double-platinum and catapulting Bedingfield to near-global stardom.

“I make a track. I pitch the vocal up because I’m not expecting to give it to anybody apart from a DJ,” Bedingfield told Billboard. “I gave it to the world’s biggest garage DJ, DJ EZ - he put it on the Pure Garage 4 compilation and poof! It becomes a big dance track and goes to No. 1. It’s absolutely crazy.”

"I did most of the recording alone in my bedroom and then tweaked it in the studio. Seriously, I recorded half of that album in my underpants"

The major labels soon came calling, and Bedingfield landed a £400,000 contract with Polydor, before Gotta Get Thru This began to gain traction overseas, hitting the Top 10 in Australia, Canada and the United States and even picking up a Grammy nomination for Best Dance Recording.

A genre-blending album of the same name followed shortly after that saw Bedingfield sticking firmly to his DIY roots: "I did most of the recording alone in my bedroom and then tweaked it in the studio,” he says. “Seriously, I recorded half of that album in my underpants."

Almost as swiftly as he arrived, though, Bedingfield seemed to disappear. After his second album failed to match the success of his debut, Bedingfield suffered a near-fatal car crash in 2004, placing the artist on a long road to recovery and sparking a change in direction: “I suddenly realised the first memory when I woke up is, ‘I’d like to try something very different’”, he recalled last year.

Bedingfield subsequently took an extended hiatus from music, travelling the world, learning languages and becoming involved in regenerative farming projects, before briefly returning to the public eye as a judge on New Zealand’s The X Factor in 2012 and more recently co-writing for other artists behind the scenes. Last year, Bedingfield made an official comeback with a series of UK shows celebrating Gotta Get Thru This’ 20th anniversary.

Bedingfield may have retreated from the public eye at the peak of his powers, but the homebrewed chart-topper that launched his career remains immensely influential, its unexpected success showing a generation of musicians that they could land six-figure record contracts with a track they recorded in their bedroom - or even in their boxers.

“The big studios are shutting down, and the little home studios are taking over,” Bedingfield said in a 2002 Billboard interview. ”If you are creative nowadays there’s no excuse to not do what you love.” It was true in 2002, and it remains true today.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.